Zitkála-Šá

Writer, musician, and political activist Zitkála-Šá, also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, was born on February 22, 1876, on the Yankton Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where she lived until she was eight.

When Zitkála-Šá was eight years old, missionaries came to the reservation to recruit children to go to White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute. Despite her mother’s pleading, Zitkála-Šá begged to go to the school with her older brother. She later wrote that she regretted the decision almost immediately, but after three years in the boarding school she no longer felt at home on the reservation either.

Throughout her life Zitkála-Šá continued to live in two worlds, using her writing and speaking to advocate for the rights of Native Americans. She taught at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, the most well-known of the off reservation boarding schools, where she came into conflict with the school’s founder and headmaster Colonel Richard Henry Pratt, whose motto was “Kill the Indian, save the man.” She studied violin and wrote articles in Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s Monthly, critical of the boarding schools and the trauma the children experienced. Prof. William F. Hanson of Brigham Young University she wrote an opera, the Sun Dance Opera, based on the sacred Sioux ritual that had been banned by the federal government.

In 1926, Zitkála-Šá and her husband, Captain Raymond Bonnin, who was also Yankton Dakota, co-founded the National Council of American Indians to "help Indians help themselves" in government relations. Many conflicts had to be resolved by Congress and the Bonnins were instrumental in representing tribal interests. Zitkála-Šá was the council’s president, public speaker, and major fundraiser, until her death in 1938.

To help us learn more, I’m joined by Dr. P. Jane Hafen (Taos Pueblo), Professor Emerita of English at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and the editor of two books of Zitkála-Šá’s writings: Dreams and Thunder: Stories, Poems, and the Sun Dance Opera and "Help Indians Help Themselves": The Later Writings of Gertrude Simmons-Bonnin (Zitkala-Sa), who graciously assisted in fact checking the introduction to this episode.

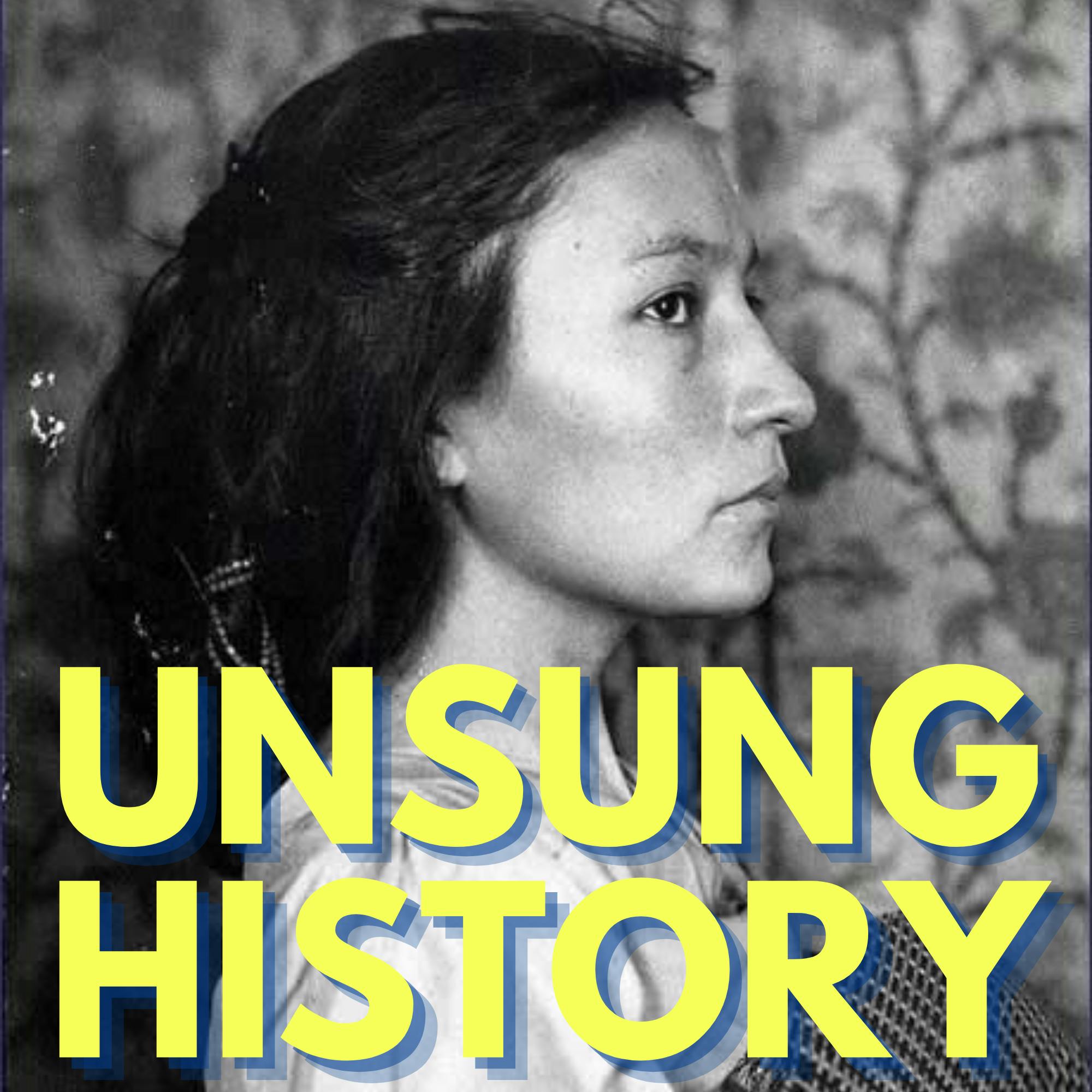

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image is: “Zitkala Sa, Sioux Indian and activist, c. 1898,” by Gertrude Kasebier, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Recommended Organization for Donation:

Additional Sources and Links:

- American Indian Stories, Zitkála-Šá

- Impressions of an Indian Childhood by Zitkála-Šá

- Oklahoma's Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes, Legalized Robbery by Zitkala-S̈a, Charles H. Fabens, and Matthew K. Sniffen. Office of the Indian Rights Association, 1924.

- Red Bird Sings: The Story of Zitkala-Sa, Native American Author, Musician, and Activist by Gina Capaldi (Author) and Q. L. Pearce (Author)

- Zitkala-Ša (Red Bird / Gertrude Simmons Bonnin), National Park Service

- “Zitkála-Šá: Trailblazing American Indian Composer and Writer” [video], UNLADYLIKE2020: THE CHANGEMAKERS, PBS.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

Today's episode is about writer, musician and political activist, Zitkála-Šá. Zitkála-Šá was born Gertie Evelyn Felker, on February 22, 1876, on the Yankton Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where she lived until she was eight. Zitkála-Šá's father abandoned the family when she was young. Her mother, Ellen Simmons, was a strong presence in her life, and Zitkála-Šá took her mom's surname as a young woman, becoming Gertrude Simmons. Later she took the Lakota name of Zitkála-Šá, meaning Red Bird. Of her mother, Zitkála-Šá wrote: "Often she was sad and silent, at which times her full arched lips were compressed into hard and bitter lines, and shadows fell under her black eyes." When she asked her mother what made her sad, her mother replied, "We were once very happy, but the pale face has stolen our lands and driven us hither. Having defrauded our land, the pale face forced us away." When Zitkála-Šá was seven, missionaries came to the reservation to recruit children to go to White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute. Despite her mother's pleading Zitkála-Šá begged to go to the school with her older brother. She later wrote that she regretted the decision almost immediately. After three years in Indiana, Zitkála-Šá returned to the reservation in 1887, where she no longer felt at home. She wrote, "During this time, I seem to hang in the heart of chaos, beyond the touch or voice of human aid. Even nature seemed to have no place for me. I was neither a wee girl nor a tall one; neither a wild Indian nor a tame one." In 1891, Zitkála-Šá returned to White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute, where she studied piano and violin. When she graduated in 1895, she gave a speech on the inequality of women's rights. Instead of returning to her home and her mother, Zitkála-Šá attended Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, where she had a scholarship. It was at Earlham that Zitkala-Sa started to gather traditional native stories to translate into Latin and English. In 1899, Zitkála-Šá started teaching at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, the most well known of the off reservation boarding schools. She quickly came into conflict with the school's founder and headmaster, Colonel Richard Henry Pratt, whose motto was "Kill the Indian, save the man." Seeing the effect that this approach had on the children, Zitkála-Šá left her teaching job at Carlisle and moved to Boston to study violin with a teacher associated with the New England Conservatory of Music. She also began to write articles in Atlantic Monthly and Harper's Monthly, critical of the boarding school and the trauma the children experienced. Zitkála-Šá returned to the reservation in South Dakota to care for her mother. She was engaged to Chicago doctor, Carlos Montezuma, who was Apache, and she encouraged Montezuma to join her in South Dakota. When he refused, she broke off the engagement.

In 1901, she published "Old Indian Legends," a book of short stories based on the Sioux oral tradition. In 1902, she married Captain Raymond Bonnin, a member of her tribe who had also survived boarding school. The Bonnins moved to the Uintah-Ouray Reservation when Captain Bonnin was assigned there. And for the next 14 years, they lived among the Ute people. Their son was born during that time. In 1913, after meeting Professor William F. Hanson at Brigham Young University, Zitkála-Šá wrote the libretto and songs for their opera collaboration, "The Sundance Opera," based on the sacred Sioux ritual that had been banned by the federal government. It was around that time that Zitkála-Šá joined the Society of American Indians, where she would become secretary treasurer. In her writing, she argued both for the preservation of native ways of life and for the rights of Native Americans to have full American citizenship. In 1916, the Bonnins and their son moved to Washington, DC, where Zitkála-Šá became even more politically active. She lectured to promote the cultural identity of Native Americans, and she lobbied for the passage of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act. Through her lecturing and writing, Zitkála-Šá was successful in raising awareness about Native American issues, and was able to impact government policy. In "American Indian Stories" in 1921, Zitkála-Šá wrote, "Now the time is at hand when the American Indian shall have his day in court. Through the help of the women of America, the stain upon America's fair name is to be removed. And the remnant of the Indian nation suffering from malnutrition is to number among the invited invisible guests at your dinner tables. In this undertaking, there must be cooperation of head, heart and hand. We serve both our own government and voiceless people within our midst. We would open the door of American Opportunity to the red man and encouraged him to find his rightful place in our American life. We would remove the barriers that hinder his normal development. Wardship is no substitute for American citizenship. Therefore, we seek his enfranchisement." In 1926, the Bonnins co- founded the National Council of American Indians to help Indians help themselves in government relations. Many conflicts had to be resolved by Congress, and the Bonnins were instrumental in representing tribal interests. Zitkála-Šá was the council's president, public speaker, and major fundraiser until her death. Zitkála-Šá died on January 26, 1938, in Washington, DC, at the age of 61. She is buried in Arlington National Cemetery with her husband Raymond. To help us understand more about Zitkála-Šá, I'm joined now by Dr. P. Jane Hafen, (Taos Pueblo), Professor Emerita of English at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and the editor of two books of Zitkála-Šá's writings.

Thank you so much for joining me. I'm really excited to talk about Zitkála-Šá, so welcome. So I thought maybe we could start, if you could just tell me a little bit about how you first got interested in studying Zitkála-Šá and, you know, kind of how you got into researching and writing about her?

P. Jane Hafen 9:01

Sure. Shortly after I finished my PhD, I had the opportunity to be a Newberry fellow at the Newberry Library in Chicago. But my dissertation was about contemporary American Indian literature and I needed a historical project because, of course, they're a historical library. And I remembered from my younger days at BYU, having seen "The Sun Dance Opera" in the stacks, and I thought, well, this would be a good topic. And sure enough, I used my time at the Newberry to study the American Indian society and a lot of other things, but it took me back to BYU where "The Sun Dance Opera" was archived, and where, at that time, there were about 20 boxes that just had paper stuffed in them. They weren't sorted. They hadn't been analyzed by an archive librarian. I think BYU kind of knew what they had, but didn't really. And so I, I went through those papers, and I found a number of unpublished stories that she had written. And that was my first publication about her, "Dreams and Thunder: Stories, Poems, and The Sun Dance Opera." And so it has the libretto to the opera, which is kind of an interesting beast in and of itself. And then I continued to work on it for a very long time. And then a couple of years ago, had her later political writing, "Help Indians Help Themselves." So I spent a large part of my career reading and writing about her works.

Kelly Therese Pollock 10:58

That's excellent. So it sounds like you sort of started to answer this. But as so many of the sort of figures and people that we maybe don't hear as much about, it's often because there isn't a large archival record of their work. But she obviously wrote a ton, a lot of it was published at the time. There's, you know, a lot to know about her. I you know, why, why do you think it is that that she isn't more well known?

P. Jane Hafen 11:24

Well, I think that I kind of anticipate that question. In American Indian Studies, she's pretty well known. This is an older edition of "American Indian Stories", which contains her boarding school narratives. And if she were to ever only be known for this, it would be an amazing achievement, because she was one of the first native authors to write without an amanuensis, without somebody translating for her or heavily editing, what she wrote. And so she tells about our her boarding school experience. Here's a wonderful contrast with her innocence and her tribal upbringing, and then what happens when she gets to boarding schools, and then some more reflective things. And then a series of short stories that are part of those collections. And those were all published in The Atlantic Monthly in Harper's Bazaar around 1900-1901. And then she collected them into this little volume called "American Indian Stories", which has pretty much been in print in various forms, for, well for 100 years. And because they're not copyrighted, they're widely anthologized, in American literature, anthologies, and American Indian Studies anthologies, and so forth. So people who are kind of leaning that way, probably would have heard of her. But it's always been my feeling that the boarding school stories are thus much of a very long and productive literary life. And it becomes more literary political, of course, later in her life, she's not writing those kinds of narratives or short stories that she was when she was younger, but she's writing a lot of very interesting discourses. In the latest book, there are testimonies before Congress, that takes a large part of it. And there's correspondence when she was president of the National Council of American Indians. And so I think her political influence has really not been served well. People are unaware of her her political involvement in the 1920s and the 1930s until her death.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:48

I want to get back to that in a minute. But first, I think people are maybe just in the past year or two starting to hear more and understand more about these boarding school stories, and what happened. I think that had been so sort of suppressed from our history for so long. But could you talk a little bit about that and her experience with going to boarding school and being sort of excited about it at the beginning, and then of course, it was a sort of terrible traumatic experience.

P. Jane Hafen 14:17

Sure. There were several very famous boarding schools, Carlisle, probably the most famous one. A lot of children were taken involuntarily. But as you note, she says in her own story, she begged her mother to go because her friends were going and of course, she uses the wonderful metaphor of going to the land of red apples and uses all this fall from Eden imagery as she says that. But what can a seven year old know about wanting to go to boarding school? So there are some people who criticize her agency. Well, my students used to criticize her agency, that she wanted to go. Well, what kind of agency does a seven-year-old have to do that? But I think that there was a growing awareness that for some, it was their only means of survival. We know that her husband Raymond went to Haskell. He was also a boarding school survivor. My own father went to the Santa Fe Boarding School. His parents allowed it because they faced the inevitable but you know, it had long term consequences.

Kelly Therese Pollock 15:27

I mean, what's so interesting, right, is that she has this traumatic experience, but then she goes and teaches at Carlisle. You know what, I guess, can you speculate, perhaps on her motivations then and going and teaching there later?

P. Jane Hafen 15:43

Well, one thing that I've tried to be careful with my work about her is to not guess at her motivations. Because she pretty much puts it out there, what she's thinking, and what she's feeling. And then you see, a lot of critics and a lot of scholars say, "Well, she did this for this reason." And she, I even read work, people who thought she was bipolar and, you know, different projecting their own imagery, on her own actions. But you think about it. Here she is a young woman. She's very uncomfortable when she goes back to the reservation. There's a transition on the Yankton reservation where she was raised, to Yankton Sioux. There's a transition from survival economy to a mercantile economy. And she, for her time, and for her age, is more educated than most people there. Where is she going to find employment? What is she going to do? The natural thing is to step into teaching, because she has a certain number of skills, and she's familiar with the system. Of course, that didn't work out well for her, as she butted heads with Richard Pratt, who was the director of the Carlisle Training School.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:02

Yeah. So then let's talk some about this, the the political work that, that she did. I, you know, I was reading something that talked about the I think it's the Indian Citizenship Act. I might have the name of it not quite right. But that that was something that she was advocating for. And I think, you know, maybe with the sort of lens of history, there are some people who say, oh, that wasn't necessarily the best thing. But, you know, I think part of it for me is I, I should have realized, but I didn't realize until I was reading about her and about that act, that not all Native Americans were citizens as of 1924. So what is, what is going on here? What? And how did that legislation sort of come to be? And what was her her role in sort of advocating for this?

P. Jane Hafen 17:55

Well, it's, it's pretty complicated. The Yanktons were unusual in that they became citizens and received the right to vote in 1895. So she was enfranchised then. And even when she lived in Utah, and other places, she she and her husband were able to vote because they were both members of the Yankton tribe. And that's certainly not true for many, many, many other tribes. But it became her political hobbyhorse during World War I, when soldiers, about 12,000 American Indians served in World War I, and they did not have the rights of citizenship. And so it's been really interesting in the last couple of years to me to see the way that she's been caught up in the centennial of suffrage when she was advocating for citizenship, which is much more than suffrage, and not just the right of women to vote, but the right of all Indians to vote. And Utah's been really funny, in particular, because they gathered her up because she lived there for about 10 years and claimed her as part of the suffrage movement when A.) she could vote and B.) Utah was the last state in the United States in 1957, to give American Indians the right to vote. So there's a lot of irony going on there. Yes, the Citizenship Act enfranchised a lot of American Indians, but there were individual states for different reasons that withheld the vote from American Indians.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:38

What were the other?

P. Jane Hafen 19:40

You're shaking your head.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:41

Yeah, well, it's all so unbelievable. Not just unbelievable, but unbelievable that I this is sort of the whole theme of the podcast right, is like why didn't I know these things? This is one of those for sure. So what what are the other things that citizenship meant? You know, being granted citizenship? Granted does not seem like the right word there, but I, you know, be being allowed citizenship. You know what, what else did that mean for them?

P. Jane Hafen 20:13

Well, it could mean, and it has not historically done so but it could mean the protection of one's civil rights. And that's huge. And as recently as the 1990s, there was a book written about how civil rights are abrogated on an on Indian reservations. There's not freedom of the press, there's not the Fifth Amendment in certain federal trials and in particular things. And so the legal history of civil rights is a really important aspect of that. But the initial, the initial idea of making American Indians, American citizens in 1924 is is what compelled that legislation. And a lot of native peoples consider themselves still citizens, citizens of their sovereign nations, and citizens of the United States.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:10

Is that still true?

P. Jane Hafen 21:12

Yes. Yeah. Oh, there are some tribes that issue their own passports.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:16

So I want to talk to you about her music. You mentioned that that's what brought you into studying her initially, this opera, The Sun Dance Opera. So this is super unique. Can you talk about what this opera was? And you know, what, what makes it such an interesting story?

P. Jane Hafen 21:36

Okay. Well, she was living out in north eastern Utah. And again, the economics of the situation, she needed employment, her husband needed employment. So they worked at what was then called the Indian Bureau. It's the forerunner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. And he was a clerk there in the office, which distributed treaty goods. And she was employed off and on as a teacher, to help out with their fiscal things. And she writes about that in one of the early issues of American Indian Magazine, which is the publication of the American Indian Society, about her experiences living among the Utes, and I think that's the actual title of it, and it's in the newer book, her essay about that. But she's out there, and she has these musical skills. And she played the violin, she played the piano. And, you know, it's pre-TV, pre-internet, pre-radio, and there were these salon gatherings. And most of the people that they associated with were not the Utes, but non- Indians. So there was a music teacher out there named William Hanson, and they got this idea: Let's write an opera. And I don't know if you want to include this in the podcast, but it reminds me of "The Muppets Go to Hollywood," you know. It's, let's write an opera. So they talked about different topics for the opera, and one of them was Chipeta, who was the wife of Chief Ouray of the Northern Utes. And they decided against that, and they decided to use the Sun Dance as a framework for an opera. So it's, it's structurally it's really fascinating because it comes with the hero, it comes with his desired love. You have the evil Shoshone singer, because he's from a competing tribe, and he wants to win the girl. And one of the most amazing pieces is a trio of gossips. And you also have a character that's called a Heyókȟa, who does everything backwards. He's kind of a trickster character, and he gets his own songs and things. And in the original productions, which were done in Utah, 1912, 1914, they were performed on stage, but they would have members of the Ute tribe and they would have a big pause. And the Utes would perform some of their traditional dances. Now, I've been told that the Yankton Sioux did not Sun Dance, but the Utes did, because they were Northern Plains tribes, so they were involved in that. And it It fits pretty consistently with stage performances, traveling performances that would happen in the early 1910s, and so forth. And one of the singers, York, he was an opera singer, and he stages it in New York, about three months after Gertrude died. But it got panned by the critics. And musically it's very difficult. It's very difficult to perform, very difficult to listen to. In 2014 there was a group of you, you'll love this, the irony of this. There was a group of siblings, who are Navajo, and their last name is Singer. And so Sarah Singer was a beautiful soprano, And her brother James, a wonderful baritone. And they staged a performance of selections at Westminster College in Salt Lake City. And it was it was pretty amazing. Their performances, I always say made it better than it was. Yeah, it would be very difficult to to restage the whole opera. I'm asked about that fairly frequently. It would be it would be difficult to do so. But they had this selections that were pretty amazing.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:53

Are there any recordings of that?

P. Jane Hafen 25:54

I think Westminster has a recording. I know, I don't know if you've seen the "Unladylike" segment. The background or selections from the Westminster recording. And Meg Singer talks about the opera in that selection.

Kelly Therese Pollock 26:13

Okay. Excellent. So I think one of the things that was most interesting to me, as I was reading some of Zitkála-Šá's writing is just how modern it seems. And you know, I don't know, if that's just because of the sort of clarity of her voice or if it's because unfortunately, you know, there are situations in some ways haven't changed that much. But, you know, you've you've obviously read much more of her work than I have, you know, what, what do you think it is about, I don't know, either the writing style or the subject matter, whatever, that that still does seem so resonant today?

P. Jane Hafen 26:52

Well, I like your description of clarity. I think she's very clear about what she does. I think she has a tremendous sense of injustice. And she recognizes that she has the platform and the voice, to try to correct that injustice. And that really drives her. You see that with the Citizenship Act, I would strongly recommend that people read "Oklahoma's Poor Rich Indians." It was an investigative pamphlet that was sponsored by the American Indian Defense Association, and she went with some guys out to Oklahoma, and they talk about the graft and terrible things that were happening. And that shows up in a variety of venues. There was the popular book "Killers of the Flower Moon," which is now being made into a movie by, directed by Martin Scorsese, that investigates those murders among the Osage people. But if you want to read the original report, read what Gertrude wrote, and you get that sense of outrage, and we need to protect, to right those wrongs. And so that report, there were echoes I think of our political circumstances these days. When it was presented before Congress, Congressmen said, "Oh, that can't be true." And they questioned her credibility. They attacked her personally, saying that what she had witnessed could not be the case. And it's, it's a fascinating document. It's it's a little long, but you see the seeds of it, still playing out in the political theater that we're experiencing today. But also in the creative theater, as this film is being made about those circumstances with the Osage in the 1920s.

Kelly Therese Pollock 28:56

Speaking of film, I think someone should make a film of her life. Why isn't this out there yet?

P. Jane Hafen 29:06

Yeah, one of the best biographies is a young adult biography, called "The Flight of Red Bird" by Doreen Rappaport. And she she did some amazing research on that original documents and photos and so forth.

Kelly Therese Pollock 29:22

Yeah. So speaking of writings and things, how can people get your books if they're interested?

P. Jane Hafen 29:30

"Dreams and Thunder" is published by the University of Nebraska Press, and "Help Indians Help Themselves" is available from Texas Tech University Press, currently having a 50% off sale. It's usually available on Kindle for only $10. So, and I don't see much of that and what I do see of it, I don't keep because I think they're her words and try to find a cause I think she would support.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:02

And if people would like to support causes that she would support do you have a recommendation?

P. Jane Hafen 30:07

Native American Rights Fund. They're involved in the legal protection of native people's rights.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:15

Excellent. I'll put a link to that in the show notes. Is there anything else that you wanted to make sure we talked about?

P. Jane Hafen 30:22

She had a very strong personality, and you see occasional conflicts with with people around her. But I do think that what really drove her and motivated her was the idea of justice. And so what I would really like to see is some history student do a dissertation on her husband, because I think he helped her with her writings a lot, especially later, when the National Council of American Indians when they were presenting testimony before Congress. They would often appear together. And because she was the president, she would sign the documents, but he had been to law school, even though he wasn't a lawyer. And he would help her prepare those documents. So there's a lot of work out, out there to be done. And Brigham Young University is very generous in allowing people into their archives. So I hope that people would continue looking at her work and looking at her husband's work.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:39

Excellent. I should recommend this as a place people should tune into if they want dissertation ideas.

P. Jane Hafen 31:48

Yeah, yeah, it would really be great to see somebody do that work.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:54

Yeah. And that's an odd twist. So often, from this time period, and earlier, you know, we see men who are the ones whose name is out there, and it was that, you know, their wives who were helping them with a lot of the writings. That's sort of a neat twist to think it's the reverse in this case.

P. Jane Hafen 32:11

Well, yeah, it is, but she had the reputation. And certainly she had the ability. And there's a lot of good work about the performativity. Now, when she was speaking before the Federated Women's Clubs, she would wear her traditional regalia, not costume but regalia, traditional tribal wear. And, of course, people are interested in the exotic aspect of it, but she would use that as a tool to get her message across.

Kelly Therese Pollock 32:41

Yeah, well, this is just a fascinating story. I loved learning about Zitkála-Šá and I'm so grateful that that you were willing to share your your time and your expertise with us.

P. Jane Hafen 32:53

Well, I'm really happy to do it. Thank you for your interest.

Teddy 32:56

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode at UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__ ___History or on Facebook at Unsung History Podcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

P. Jane Hafen

Dr. P. Jane Hafen (Taos Pueblo) is a Professor of English at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She serves as an advisory editor of Great Plains Quarterly, on the editorial board of Michigan State University Press, American Indian Series, on the board of the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, and is an Associate Fellow at the Center for Great Plains Studies. She is a Frances C. Allen Fellow, D'Arcy McNickle Center for the History of the American Indian, The Newberry Library, and is a Clan Mother of the Native American Literature Symposium. She received the William H. Morris Teaching Award for the College of Liberal Arts, UNLV. She edited Dreams and Thunder: Stories, Poems and The Sun Dance Opera by Zitkala-Ša, co-edited The Great Plains Reader, and is author of Reading Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine and articles and book chapters about American Indian Literatures. She edited a collection of essays, Critical Insights: Louise Erdrich.