The Suffrage Road Trip of 1915

In September 1915, four suffragists set off from the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, California, in a brand-new Overland 6 convertible to make the 3,000-mile drive across the country to deliver a petition for women’s suffrage to President Woodrow Wilson on the opening day of Congress in December. Along the way they faced illness, terrible driving conditions, and opposition to women’s suffrage.

Joining me to help us learn more about the road trip, and especially the unsung Swedish immigrant heroines, driver Maria Kindberg and mechanic Ingeborg Kindstedt, is historian and activist, Anne Gass, author of the 2021 book, We Demand: The Suffrage Road Trip.

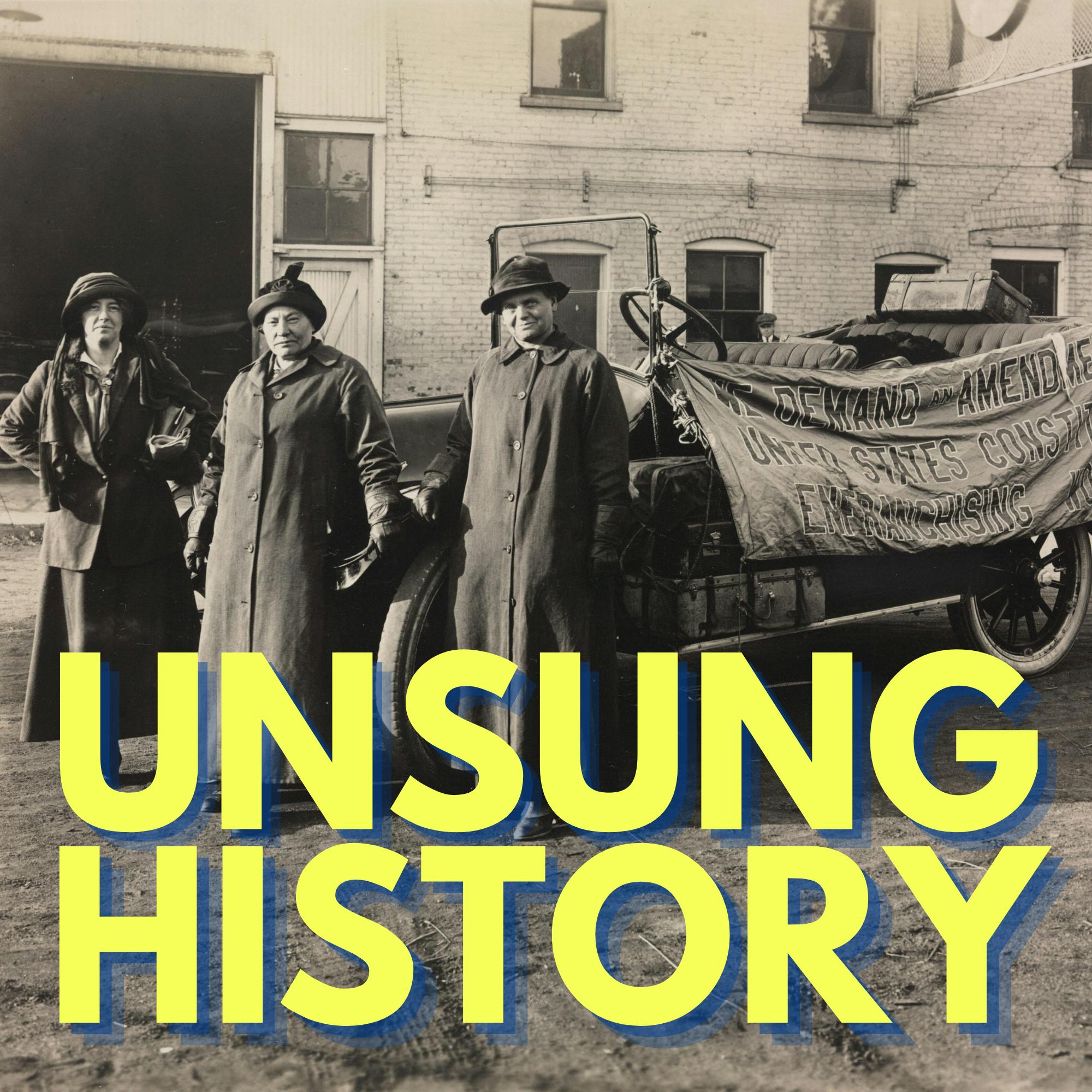

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image is: “Suffrage envoy Sara Bard Field left and her driver, Maria Kindberg center, and machinist Ingeborg Kindstedt right during their cross-country journey to present suffrage petitions to Congress, September-December. United States Washington D.C, 1915,” Public Domain, Located at the Library of Congress. The audio recording clip is: “Fall in Line (Suffrage March),” Written by Zena S. Hawn, and Performed by the Victor Military Band on July 15, 1914, Public Domain, Internet Archive.

Selected Additional Sources:

- “Rhode Island’s Two Unheralded Suffragists,” Small State Big History, by Russell DeSimone, January 11, 2020

- “Historical Timeline of the National Womans Party,” Library of Congress

- “Traveling for Suffrage Part 1: Two women, a cat, a car, and a mission,” by Patri O'Gan, National Museum of American HIstory, March 5, 2014

- “Maria Kindberg,” Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame

- “Ingeborg Kindstedt,” Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame

- “Sara Bard Field (1882-1974),” by Tim Barnes, Oregon Encyclopedia

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. Today's episode is about a 1915 cross country road trip made by suffragists to demand women's suffrage. At the 1915 World's Fair, held in San Francisco, California, and called the Panama Pacific International Exposition, the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CU) sponsored a freedom booth, where they collected signatures for the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which would grant women's suffrage. On September 15 and 16th of that year, the CU held a Women Voters Convention at the fair. By that point, the CU claimed to have collected 500,000 signatures on the petition. CU founder Alice Paul wanted to create a splash, bringing the petition to President Woodrow Wilson in DC and the CU nominated two envoys to drive across the country with the petition, stopping along the way to drum up support. The two envoys selected were poet Sara Bard Field and drama critic Frances Jolliffe. Both women were gifted orators, longtime suffragists, and they represented Western states where women had already won the right to vote. With the selection of the envoys, the CU still faced the problem of how to get them to DC. Luckily, two Swedish immigrants and suffragists Maria Kindberg and Ingeborg Kindstsedt had traveled by steamship from Providence, Rhode Island, through the recently opened Panama Canal to San Francisco to attend the Women Voters Convention, and had already planned to purchase a car there to drive back across the country. They agreed to drive the petition and the envoys to DC. Maria purchased an Overland Six convertible and took on the role of driver. Ingeborg served as the mechanic for the trip. With no major interstate highways yet crossing the country, they traveled on muddy and washed out roads and faced both desert heat and Midwestern snowstorms. Frances Jolliffe left the expedition almost as soon as they began due to an unspecified illness. Although there is speculation that she simply realized the trip would be too difficult. She joined up with the group leader on the East Coast. Sara Bard Field, Maria Kindberg. And Ingebord Kindstedt kept up a grueling pace, traveling 3000 miles over 10 weeks and crossing 18 states on their way to DC. CU organizer Mabel Vernon travelled by train ahead of the car as the one woman advance team arranging for parades and parties and meetings with governors, mayors and suffrage leaders for the trio in towns along the way. Although Maria and Ingeborg were fellow suffragists and Ingeborg lectured on suffrage in Rhode Island, 33 year old Sarah did all of the public speaking on the trip. The image CU was looking to portray was that of young, fashionable and articulate suffragists from western states, and Swedish immigrants Maria, age 55, and Ingeborg age 50 did not fit the bill. Much of the press coverage of the trip focused on Sara, ignoring the essential contributions of Maria, and Ingeborg. As a result, tensions grew between Sara and Ingeborg. When Sara was interviewed about the trip many years later, she claimed that Ingeborg had threatened to kill her before the end of the journey.

When they reached the East Coast, Frances Jolliffe rejoined the car for the last leg of the trip to DC. On December 6, 1915, the group finally reached their destination. The Overland Six, festooned with a banner declaring, "We Demand an Amendment to the United States Constitution Enfranchising Women" drove into DC in time for the opening of the 64th Congress and the First National Convention of CU held in DC. A procession of 2000 women escorted the envoys in a parade to the US Capitol for a reception by a congressional delegation. President Wilson met with a smaller group of the suffragists where Sara Bard Field presented him with a copy of the petition. President Wilson welcomed them, but declined their request to mention women's suffrage in his upcoming annual address. He did promise to keep an open mind and confer with Congress. Women's Suffrage amendments were introduced in the House and Senate in the following days, but they didn't pass. And it would be another three and a half years before the amendment would pass in Congress. To help us understand more about the 1915 suffrage road trip. I'm joined now by historian and activist Anne Gass, author of the 2021 book, "We Demand: The Suffrage Road Trip." Before my conversation with Anne, please enjoy a clip of a 1914 recording of "Fall in Line," the suffrage march written by Zena S. Hawn and performed by the Victor Military Band. This recording has just entered the public domain for the first time due to the Music Modernization Act. Hi, Anne. Thanks so much for speaking with me today.

Anne B. Gass 7:43

Thanks for having me on Kelly.

Kelly Therese Pollock 7:45

Yeah. So tell me first how you first got interested, how you even heard about this suffrage roadtrip and how you got interested in writing about it.

Anne B. Gass 7:53

Yeah, so it starts back, almost 20 years ago, I started researching my great grandmother who was a suffrage leader in Maine 100 years ago. And, and in the course of that research, I came across references to this cross country road trip that happened in 1915. And I always thought that must have been one hell of a trip in 1915. You know, and so what was that like and and I just thought if that would be it would be a total trip to just retrace their journey and and try and learn more about it. And so I didn't finish that first book about my great grandmother until about 2014. And so it wasn't till 2015 that I was able to, to retrace their journey and and that was just such a great learning experience for me. But then, in the course of, you know, spending almost 10 weeks coming across the country, retracing their route, I started realizing that everything that had been written about this trip was from the perspective of this sort of middle class white, younger woman, Sara Bard Field, and two Swedish women who were pivotal to the trip's success, you know, were hardly even mentioned sometimes, sometimes not at all. So that just really piqued my curiosity.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:14

So in addition to retracing their steps to doing this journey, and I know you mentioned toward the end in your your afterword, or acknowledgments or something that that you actually interviewed people along the way, like League of Women Voters and stuff along the way. So tell me a little bit about that. But then also the the other kinds of research you did to learn more about the trip, and especially these two women, these two Swedish women.

Anne B. Gass 9:40

Yeah, so I, I did a whole lot of different types of research. I mean, on the way across the country, I was really interested in understanding what difference having had the vote meant for women in the preceding 100 years, the at least the women in the states that had enfranchised women through some sort of state action, by 1915, and and so that's why I did reach out to League of Women Voters and women's rights activists and this sort of, and a lot of them said, you know, "The suffrage centennial is coming up. And, you know, the stories that we've been telling about the suffrage movement in the US are incomplete." They don't talk about Black suffragists. They don't talk about, you know, Hispanic, or Asian American women who were working on this. And they often they do, they did sort of cover labor to some degree to a better degree. But still, the focus was very much on white middle class women who were affluent enough to be able to devote, you know, most or all of their time to suffrage, and those have become our suffrage sort of heroes over the years and, and so I really heard that, from so many places, it was impossible to follow through with my original intent, which was to write a nonfiction account of this, this trip. The other reason, of course, was that the only person who really left much of a written record was Sara Bard Field, who was on the trip. But the two Swedes to my you know, as far as I was able to find out had written very little, really nothing about the trip itself. So it was pretty hard to find out much more about what they thought. One thing I did discover was that they had some somehow somebody had managed to get articles into Swedish language newspapers. And amusingly, they typically did not even reference Sara Bard Field, or this other woman, Frances Jolliffe, who was supposed to be on the trip. They only talked about the Swedes, and I just thought that was marvelous. I mean, just turnabout is fair play. I mean, if you if you do, like completely ignore my presence on this trip, I get to ignore yours when I when I control the story. And so that's I, you know, I kind of tuck that into the book as well, because I just thought it was so interesting that that happened.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:04

So you decided to make this into a novel, into fiction, so that you could sort of get into their heads a little more and sort of see it from their point of view. What what does that process look like sort of figuring out, you know, how much of the sort of documented story to include, how much to sort of stretch your historical imagination? Like, what what does that look like putting it all together?

Anne B. Gass 12:29

Yeah, that's an interesting question because it was hard for me. I'd never written a novel before. But also, I wanted very much to make this a tribute to the grit and determination of the women who made the trip and the suffrage movement that launched it, because I have, you know, a huge amount of respect for the vision and the commitment and the just the grind that they had to go through to get there. So but I did quite a bit of research into Swedish immigration history so I could understand what you know what the reasons why so many Swedish, millions of Swedish people left the country and moved to the US primarily in waves, successive waves beginning in the mid 19th century. And I'm sorry, I Ingeborg and Maria came later around 1888 and 1890, respectively. They didn't know each other in Sweden either. They met in Providence, Rhode Island, where they both lived. Anyway, I did a lot of that kind of research. I also was really interested in what else was happening in early 20th century America and and that's where I got interested in the Industrial Workers of the World, because Ingeborg, one of the Swedish women, was a member of the IWW, and would have known about Joe Hill who was a fellow Swede. And so one of the licenses I guess, licenses that I took with the book was having her meet with him in Salt Lake City when they came through there because he was in jail there. He was in prison in Sugar House Prison. He was just weeks away from being executed for a crime that, you know, in retrospect, it looks almost certain that he did not commit, but so and a lot of people thought that he was he was arrested and eventually executed for being a radical labor activist. So that kind of thing, I was really interested in this, this chatter that I was hearing a lot about leading up to the 2020 Centennial about how racist the white suffragists were, and that kind of troubled me because I that's not wrong. Obviously, there were, you know, quite a number of them who were just out and out racist. But I also felt like it was unfair to the suffragists because the whole country was racist. It kind of you know, tagged them with a label that the whole country really still needs to own. And, and so I kind of delved into that background as well. And and, and have them meet with Ida B. Wells Barnett when they come through Chicago, which again, they didn't do, but you know, she has a thing or two to tell them about what she thinks. And so I, it was really just trying to kind of weave together this background to the trip, because, you know, there's only so many times you could say, "Oh, they arrived in the city, and they had a bunch of suffrage meetings, and they met these suffrage leaders, and then they go to the next city, and it was hard, you know?" So I mean, part of it was just to add some more interest and depth to the story.

Kelly Therese Pollock 15:34

Yeah. And so I think one of the thing that comes through so strongly in your story is the sort of physical discomfort of this trip. They, you know, as you mentioned, this is a long, grueling journey. But can you talk some about that, that piece of it and, and why you sort of included that, that sort of sensory description of what this journey was really like for them?

Anne B. Gass 16:02

Yeah, I think that goes back to my initial interest in, in this story, right, because I recognize that in that, you know, in 1915, cars were still relatively new. I mean, they weren't even a decade old in terms of their availability. And, and for women to make that trip alone would have been unusual. Nowadays, we send women into space, and don't think too much about it. But, you know, a cross country road trip by women, this wasn't the first one that was done, but it was close to the first. So I was just sort of curious about what it was like, and, and I actually ended up buying myself a new car in San Francisco, and driving that across the country; but my car had air conditioning and, and good shocks, and the roads were much better. And it was exhausting. I mean, I, my drives, my daily drives are much shorter than theirs. I tried to mimic their itinerary. And so what I was filling up the rest of my time interviewing people and doing research at historical, you know, libraries and museums, and so I, I was busy. And I also did sometimes some talks, so I was feeling quite pressured and busy. And I, I, I thought, "Well, if I'm feeling this way, then it must have been so much worse for them." So I thought it was just important for people to understand how physically difficult that trip was. And that, really, this was an example of the extraordinary efforts that women had to undertake in order to win the right to vote. This is just one example of that. But you know, there were, there were quite a number of others. And in US history, that was kind of unprecedented. Nobody else had to fight this long. Well, I mean, obviously, that's not true for Native Americans and, and Black African Americans, but, you know, who went through far worse, but but, you know, just for men, especially for white men, I mean, if they want to enfranchise a group, you know, say, "Well, okay, now all immigrants, even if they don't own property can vote," they just did it, you know. They didn't have to go through this multi generational fight for those rights. And so I just thought it was important to highlight the discomfort of the trip. And it also just added color to the stories. And I did Incidentally, I mean, some of the things that I highlighted did actually occur on that trip. They did get lost in the desert; and they do fail to turn up at a, at an event in Kansas; they do get stuck in the mud. You know, there's these things did happen. And I just think that they were part of the reality of their trip.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:42

Yeah. It's like, oh, my gosh, are they actually gonna make it? You know, even you know, it's real history, and so of course, we know that they do. But yeah, several times along the way, it feels like there's just roadblock after roadblock literally.

Anne B. Gass 18:57

Yeah, that's right. And I think, you know, that, again, that speaks to the incredible tenaciousness of these women. You know, in the, in the spring, in the winter and spring leading up to this, this planned trip, the Congressional Union, which launched the program, or the journey, was thinking that they would send 100 cars across the country and I just, in retrospect, that just seemed like lunacy to me. I mean, to have first of all to find 100 women to drive those cars and you know, I think would have been a stretch. They couldn't even find just one. I mean, until the Swedes showed up in the Congressional Union's booth at the Panama Pacific International Exposition they you know, they didn't have anybody and and the trip was just weeks away. So like just the the mechanics and the logistics of getting all those cars fueled and getting them across a pass and a blizzard, you know, like how on earth would they have done that and it really boiled down to these incredible women and and and their results. The other thing I thought was really important to note, and this as a woman of a certain age myself, is that the Swedes were middle aged. I mean, they were, the younger one was 50, Ingeborg and Maria was 55 years of age at this trip, and, you know, to undertake such a grueling experience at that age, and they drove and maintained the car too. I mean, which they they got almost they got very little credit for along the way, and certainly, historically. I think that's amazing. I couldn't freakin' you know, maintain a car at my age right now. If you if you put a gun to my head, I mean, it just wouldn't happen. And, you know, cars were maybe simpler then. But still, it was quite an achievement.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:43

Yeah. So one of the things that, you know, every time we think about the suffrage story, and comes out here as well, is that it's not just that there are antis, so anti suffrage people; but there are disagreements within the pro suffrage community about how to do this, do we want a national amendment? Do we want it state by state? Should we try to push for the inclusion of African American and so or not, you know, like, what, what all of this looks like? So can you speak some to that, and in your research, what you found out about the those sort of competing visions of what suffrage should look like?

Anne B. Gass 21:22

Yeah, that's such a great question. And I again, I have to sort of go back and say that my understanding and my thought process around this has really evolved through the process of writing my first book about my great grandmother. And and what I came to believe, rightly or wrongly, is that I think a lot of it had to do with and understood a lot of the disagreements had to do with what, how people perceive the proper role of women. And the Congressional Union really was more radical in their views on that. You know, I think they really foresaw the the winning suffrage as just the end of the first phase, I mean, that there was a whole lot more work to be done. And that, of course, you know, we know that's true, because Alice Paul went along with some other folks went on to author the, the Equal Rights Amendment and arranged to have that introduced in Congress in 1923. But the National American Women's Suffrage Association, which was the sort of legacy more kind of staid group really seem to see it seemed to think of voting rights as kind of the end of the story in terms of what women you know, needed and should have, and, and not so much, we're so much focused on all those other rights, that, you know, they there was a real belief among even a lot of among a lot of suffragists that women belonged in the home that they, you know, that that was their proper sphere. And they, you know, they should be making a nice home for their husband and children and taking care of their loved ones. And that's all. So a lot of it has to do with, you know, people's perceptions of women's roles. But I think the other thing is, is whether or not women should be involved in politics, and just the political strategies that they were using, and social movements that unroll, unfurl kind of over decades, as this one did always result in changes, right. Like, I mean, like, even in the Civil Rights Movement, I mean, Martin Luther King, and the and the, you know, the more peaceful approach that to demanding rights was, you know, a strategy that was embraced by a lot, but then it became more militant after that. And we've seen that also in the the women's rights movement. I mean, there initially, there was a focus on women's rights, but gender rights, you know, were you know, there are a lot of a lot of feminists who did not believe that they should be supporting LGBTQ rights along the same at the same time, and that. You know, social movements do change over time. And that was certainly the case within the suffrage movement. And I think the other thing I would just note, and I don't really highlight this in the book, but this trip in 1915, was really designed to unite suffragists across the country behind what they refer to as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which is eventually, you know, what the 19th Amendment, it, you know, becomes the 19th Amendment. The because there was an alternative, referred to as the Shafroth Amendment, which was another option for an amendment to the US Constitution, but it was kind of crazy. I mean, it would have it would have been just it would have required so much more work in order to get women the right to vote. And it would have ultimately driven that decision back to the states to decide not through ratification of the amendment which they would have had to do or but but also through other state actions. That's an example of the differences in strategy. There was there was a lot of focus on states rights versus federal rights. And and so there were suffragists who believed that the Shafroth Amendment was the way to go because it would win over those people who were much more focused on states rights. But he just It was a crazy idea. And and I think it was the right decision to just go after the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, because of course, the other thing was that the states' rights argument was really at its core racist, and it was really about not wanting to sort of interfere with Southern states' decisions to disenfranchise their Black populations.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:46

As you mentioned there, Ingeborg and Maria didn't leave much in the way of their own records. So what are you said that you looked at Swedish immigration, but what are the ways that you sort of tried to get into what they might have been thinking and feeling and doing in this trip?

Anne B. Gass 26:05

Well, I did know a little bit about their backstories I based on some information I was able to get from the Swedish I'm going to get the name wrong, that Swedish like National Museum or something. So I knew that, for example, Ingeborg had tried to go to the officer training school set up by the Salvation Army, prior to her immigration. So I kind of wove that into the story. And I knew that Maria had become a midwife, and was a quite a successful midwife. And so I kind of used that in various ways to weave that into the story. She was always described by Sara Bard Field and Mabel Vernon and some others, as you know, Maria was the sort of more maternal, caring, loving and warm individual, whereas Ingeborg was always viewed as, or described as kind of this irascible, kind of resentful and an irritable kind of person. And I, I just I thought about that a lot. And I started to think, "Well, wait a minute, maybe her irritation was justified because she would have been able to see as they came across the country that sometimes they weren't even mentioned, when they were on the trip." So I, I, I kind of used that as an excuse, like that was her personality anyway, yes, maybe but but she has some reasons to be to be angry about how she was being treated. And I guess the other thing that what really struck me in researching the early 20th century was how much it seemed like a, you know, early 21st century America. I mean, the as I came across the country in 2015, Donald Trump wasn't yet the official candidate for the Republicans in the presidential election, but he was making a lot of noise. And there was still though a lot of hope that Hillary would be the women's the country's first woman president. Obviously, that didn't happen. But as I was writing the book, there was a tremendous amount of anti immigration sentiment coming out of the administration and its supporters, some, you know, a fair amount of misogyny as well, and, and in anti labor stuff. And I just thought, "Wow, I mean, how far have we actually moved from 1915? It doesn't feel like that that far right now. So I kind of wove that into the book as well, just to try and show, I mean, for me, I was trying to make sense of what was going on in our time, you know, against the backdrop of the country's history, I guess.

Kelly Therese Pollock 28:39

So in the book, you have Maria and Ingeborg in a relationship. Is there any evidence? It obviously could be the case, but is there any evidence that they were, in fact, in a relationship?

Anne B. Gass 28:51

Yeah, I mean, I, they had lived together for 20 years. I mean, the census shows that they lived together for 20 years in Providence and, and while that wasn't uncommon, the so called sort of Boston marriages, those tended to be Boston marriages tended to refer to as I understand them more to more affluent people, women who lived together. And neither one of them ever married. There's no record of them, either of them ever having a child. So you know, it wasn't out of convenience, you know, after a marriage failed, or a husband died or something that they got together. And then when Maria died, actually she died by suicide, we don't know why, in 1921. But she left all of her her assets to Ingeborg the way you might to a spouse, right? I mean, as opposed to somebody you just roomed with, and that her will was actually challenged by Maria's siblings, two of Maria siblings who still lived in Sweden. So from Sweden, they reached out and brought suit against Ingeborg and were unsuccessful in doing that. The court upheld the will and so I just thought that was really interesting. And in writing them, you know, writing the book with them as lesbian partners may allow me to highlight some of the the queer history of the suffrage movement, which is another area that's just begun to emerge. I think other scholars, you know, have really tapped into that much, much more so than I have, but I just thought it was an important stream to bring up.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:26

Yeah, was there anything, as you were writing this, as you were doing your trip, as you were researching, as you were writing, that that really sort of jumped out at you surprised, you know, any, any pieces of this that I mean, the whole thing is sort of a wild story. But you know, any, any sort of one thing that there really stayed with you?

Anne B. Gass 30:46

I would say a few things. One is that it just, you know, how hard women had to work to win the vote. I mean, we as many times as you say that it's hard to really grapple with until you engage with the history and trace kind of what had to happen. And I think how I was also struck by just how, how close it came to not happening, I mean it or to taking longer than 1920; because it came down to the ratification of the what becomes the 19th Amendment comes down to just one state, Tennessee, a southern state, right, you know, a state with a slavery history, and won there by one vote. And so it could easily have gone the other way. And I you know, just what would have happened if they hadn't been able to get it ratified. And obviously, that all happens after the 1915 road trip. But I'm just, you know, just sort of engaging with that whole history amazed me. And there was another thing that when I met with a League of Women Voters president out in Sacramento, California, she just said to me, "Why don't women run? Why don't they want to run for office?" And I just looked at her.I felt completely guilty, because I've been urged to run for office a number of times and had refused. And, and I that that conversation stayed with me as I came across the country, and in the years afterward. And so I one of the reasons it took me so long to write this book was I ran for office in 2018. I ran for state rep, unsuccessfully. But I you know, I think that it really made me feel like I had to step up. And I think women do to take on these offices, because if we're not there to make the laws and on the policy, it may not be made in the ways that we want it to be.

Kelly Therese Pollock 32:44

Yeah, tell listeners how they can get your book.

Anne B. Gass 32:48

The book is on Amazon. And there's a there's both a e-version, as well as there's a hardcover and a soft cover. But also, the publisher I use was Maine Authors Publishing, and that's in Maine. So if you just Google that and go to their bookstore page, you can search for "We Demand: The Suffrage Road Trip."

Kelly Therese Pollock 33:10

Do you have any other books coming up, anything you're you're thinking about?

Anne B. Gass 33:14

I'm working on a few different projects. It's none is really well underway at this point. I think it's I part of my problem is that I'm I'm too much of an activist to be a good writer. It's hard for me to sit my rump in a chair and just write and write and write. I'd like to get out in the community and serve on boards. I'm on my town council now, contemplating on a run for state rep in 2022. So um, you know, it's hard for me to find the time, but yeah, I got some projects.

Kelly Therese Pollock 33:44

Is there anything else that you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Anne B. Gass 33:47

I guess the other what's the other point I guess I'd like to make and again in the again in the context of these extraordinary times that we're in now is that the Woman Suffrage Movement was a peaceful revolution that unfolded over more than seven decades, if you trace it back to the Seneca Falls Conference in Western New York, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and friends and in some degrees, that's in some ways, that's kind of an arbitrary date. And I think it's, you know, it's probably more appropriate to take it back to when the Constitution was first adopted, which is 132 years, you know, before the 19th Amendment was passed. But it was always peaceful and, and unlike the attack that took place on January 6 at the Capitol, I mean, these women just gave everything some of them just gave everything to this cause. They grew up and they grew old in the cause and still died without seeing the right to vote. So I think it's that's a pretty unusual history around the change of, you know, social movements and change and I just think they should be recognized for that.

Kelly Therese Pollock 35:02

Yeah, well Anne, thank you so much for speaking with me. This was a really fun book. I enjoyed reading it a lot and and I knew nothing about this road trip before. So it really is sort of the, the Unsung hidden History that we like to highlight here. So thank you.

Anne B. Gass 35:21

Good. Thanks so much. And thanks so much for your podcast. It's a wonderful one and I I'm enjoying every one that I listen to.

Kelly Therese Pollock 35:28

Thank you.

Teddy 35:29

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode at UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History. Or on Facebook @UnsungHistoryPodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Anne Gass

I am the author of We Demand: The Suffrage Road Trip, a historical fiction novel based on the true story of a 1915 road trip for the suffrage cause. It is illustrated by my daughter, Emma Leavitt of Solei Arts.

My first book was Voting Down the Rose: Florence Brooks Whitehouse and Maine’s Fight for Woman Suffrage, a biography that came out in 2014. It's about my great-grandmother, a Maine suffrage leader from 1913-1920. Both are published by

Maine Authors Publishing.

I am a “women’s rights history activist” - I love sharing what I've learned about this rich history with others, hoping to inspire their activism!