The Red Summer of 1919 & Black Resistance

In 1919, racial tensions in the US, exacerbated by changes brought about by the first wave of the Great Migration and by the return of Black soldiers who demanded equal citizenship from the country they’d fought for, boiled over into a summer of violence. In Washington, DC, 39 people died after days of fighting between white mobs and Black citizens who stood their ground and fought back. The events of the Red Summer are just one example of the ways that Black Americans have resisted white supremacy. Our guest this episode, Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson, the Michael and Denise ‘68 Associate Professor of Africana Studies and the Chair of the Africana Studies Department at Wellesley College and author of We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance, discusses five remedies by which Black people have responded and continue to respond to white supremacy.

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “My way's cloudy,” a traditional negro spiritual, arranged by H.T. Burleigh, and performed by Contralto Marian Anderson and a backing orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon, in Camden, New Jersey, on December 10, 1923; the recording is in the public domain and is available via the Library of Congress National Jukebox.

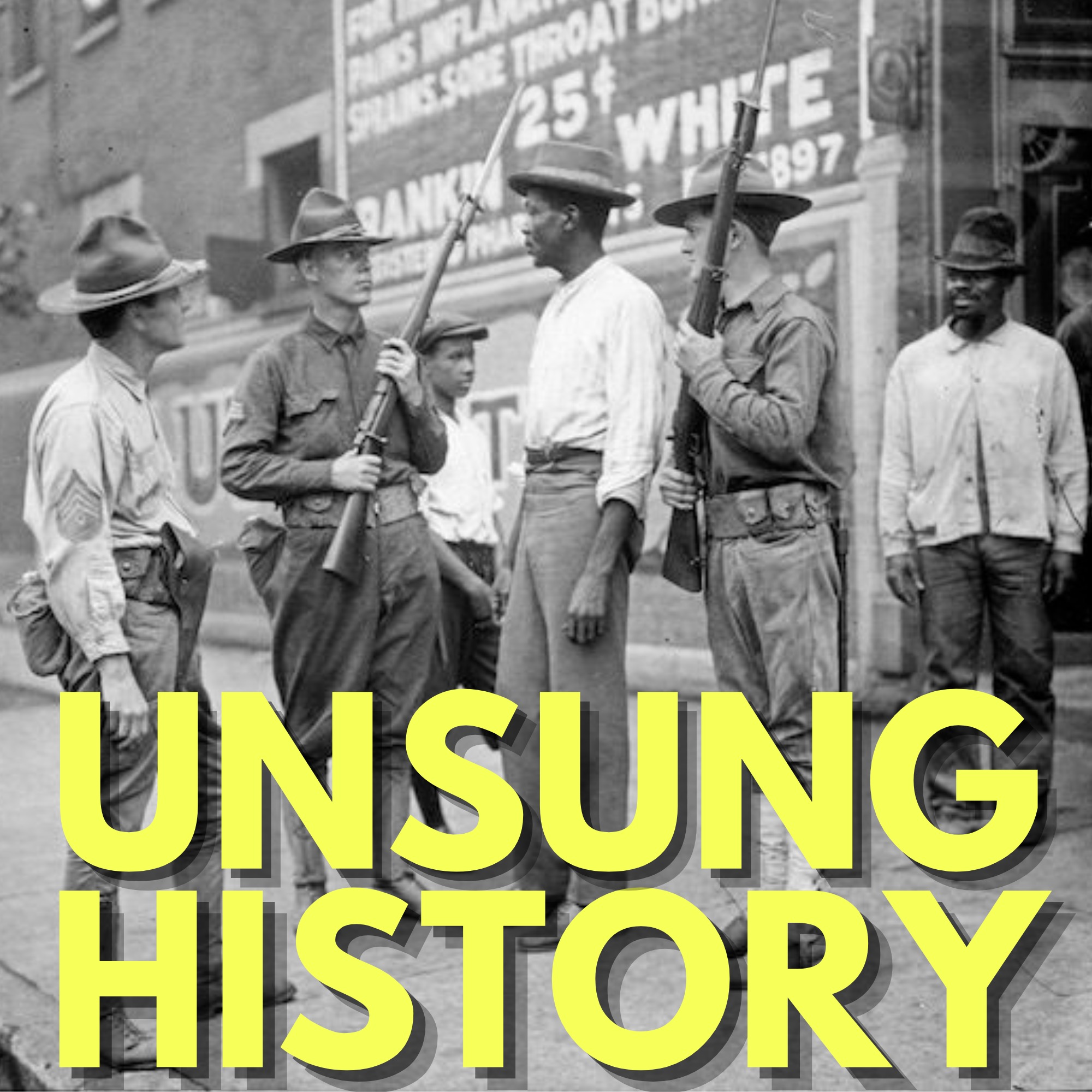

The episode image is “National Guard during the 1919 Chicago Race Riots,” photograph by Jun Fujita; the photograph has no known copyright and is available via the Chicago History Museum, ICHi-065477.

Additional Sources:

- “Close Ranks (1918),” W.E.B. Du Bois, Editorial from The Crisis, Reprinted on BlackPast.

- “Returning Soldiers (1919),” W.E.B. Du Bois, Editorial from The Crisis, Reprinted in American Yawp.

- “African-American Troops Fought to Fight in World War I,” by Richard Goldenberg, U.S. Department of Defense, February 1, 2018.

- “An American and Nothing Else: The Great War and the Battle for National Belonging,” Yale University Library Online Exhibitions.

- “Racial Violence and the Red Summer,” National Archives.

- “Red Summer of 1919: How Black WWI Vets Fought Back Against Racist Mobs,” by Abigail Higgins, History.com, July 26, 2019.

- “The Red Summer of 1919, Explained,” by Ursula Wolfe-Rocco, Teen Vogue, May 31, 2020.

- “Hundreds of black deaths during 1919’s Red Summer are being remembered,” PBS NewsHour, July 23, 2019.

- “The Red Summer of 1919,” by Julius L Jones, Chicago History Museum, July 26, 2019.

- “Red Summer: The Race Riots of 1919,” National WWI Museum and Memorial.

- “The deadly race riot ‘aided and abetted’ by The Washington Post a century ago,” by Gillian Brockell, The Washington Post, July 15, 2019.

- “One Hundred Years Ago, a Four-Day Race Riot Engulfed Washington, D.C.,”by Patrick Sauer, Smithsonian Magazine, July 17, 2019.

- “How a Brutal Race Riot Shaped Modern Chicago,” by Adam Green, The New York Times, August 3, 2019.

- “Black Communist in the Freedom Struggle: The Life of Harry Haywood,” by Harry Haywood, Edited by Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, University of Minnesota Press, May 8, 2012.

- “Our History,” NAACP.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

Kelly 0:38

In July, 1918, in the middle of what was then called the Great War, WEB DuBois, wrote an appeal to Black Americans in "The Crisis," the official publication of the NAACP, "Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances, and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder, with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy. We make no ordinary sacrifice, but we make it gladly and willingly with our eyes lifted to the hills." The statement was out of character for DuBois, who was usually outspoken in his demand for racial equality. And by the end of the war, Du Bois had a new message for the 380,000 African Americans who served in the Great War, 200,000 of them in Europe. He wrote in The Crisis in May, 1919, that the country they were returning to was a shameful land, one that lynched, disenfranchised, stole from, and insulted Black Americans, concluding, "We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting. Make way for democracy. We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why." DuBois was not alone in the sentiment. Soldiers returned to United States simmering with racial tensions. Before and during the war, half a million African Americans had moved from the south to northern and midwestern cities, in the first wave of the Great Migration, hoping to leave behind Jim Crow discrimination, and having been recruited by northern factories. However, white laborers, some of them recent immigrants from Europe, resented the influx of Black workers, especially as some industries used Black workers as scabs during labor strikes. The return of white soldiers who found their jobs had been filled with Black workers and the return of Black soldiers who demanded equal citizenship in the country they'd fought for, exacerbated an already volatile situation. Throughout 1919, from April to November, in what NAACP Field Secretary James Weldon Johnson termed, "The Red Summer," for its bloodiness, racist white mobs across the country attacked African Americans, who in turn defended themselves. In July, 1919, Jamaican American writer, Claude McKay, who had witnessed violent white mobs while he worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad, published a sonnet, titled, "If We Must Die," in the Liberator Magazine. The sonnet urged the hunted to resist, ending, "Like men, we'll face the murderous cowardly pack, pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back." In the autumn of that year, Dr. George Edmund Haynes, a Black social worker and statistician working for the Department of Labor, wrote up a report on the summer's violence in preparation for a Senate investigation. Haynes identified 38 separate racially motivated riots across the United States that summer, along with lynchings of at least 43 African Americans between January 1 and September 14 of that year. According to later research, more than 250 African Americans were killed in riots in 1919, with historian John Hope Franklin calling it, "the greatest period of interracial strife the nation has ever witnessed." In Washington, DC, the violence was sparked by the reports of a white woman, the wife of an employee of the National Aviation Corps, who claimed that two Black men had attacked her and had tried to steal her umbrella. As the story spread, it was sensationalized, and a group of white veterans decided to march on a Black neighborhood called Bloodfield on July 19, beating one of the alleged attackers, but also indiscriminately assaulting African Americans there who had no connection to the original incident. When the police finally intervened, they arrested more Black people than white. The riots continued for days, incited by news reports. An article in the front page of the Washington Post on July 21, with the headline, "Mobilization for Tonight," reported that all available servicemen were requested to meet. "The hour of assembly is nine o'clock and the purpose is a cleanup that will cause the events of the last two evenings to pale into insignificance." Since many of those same service members had been rioting the night before, it was unclear whether they were being called to stop the mob or to join it, and the NAACP later blamed the article, in part for the ensuing maelstrom. Black residents of DC armed themselves for the coming conflict, buying an estimated 500 guns on just that day. 2000 armed Black veterans got information to defend their neighborhood. They didn't back down when the police ordered them to disperse and jabbed at them with bayonets. The next day, President Wilson ordered 1000s of troops from nearby bases to the city to quell the riots. But it was heavy rain that finally brought an uneasy peace. An estimated 39 people were killed, either dying immediately or later succumbing to the injuries they sustained during the riots. In the aftermath, the Black residents of DC met a week later to form a self defense fund for African Americans arrested in the riots. The events inspired others. As a self identified southern Black woman wrote to The Crisis, "The Washington riot gave me a thrill that comes once in a lifetime. At last, our men had stood up like men. I stood up alone in my room and exclaimed aloud, "Oh, I thank God, thank God. The pent up horror, grief, and humiliation of a lifetime, half a century, was being stripped from me." In the week long Chicago riots later that summer, another 38 people died. Over 500 were injured, and over 1000 Black people on the Southside of Chicago lost their homes. At the end of September, 1919, in one of the deadliest racial conflicts in US history, several 100 African Americans were killed by white mobs in Elaine, Arkansas, in response to union organizing by Black farmers. Black veteran Harry Haywood, later reflected on his return to the US in 1919, writing, "It came to me then that I had been fighting the wrong war. The Germans weren't the enemy. The enemy was right here at home." The NAACP grew rapidly that year, with more than 90,000 members by the end of 1919.

Kelly 10:16

Joining me now to discuss Black resistance to white supremacy in many forms, including in Washington, DC in 1919, is Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson, the Michael and Denise '68, Associate Professor of Africana Studies, and the Chair of the Africana Studies Department at Wellesley College, and author of, "We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance."

Kelly 11:42

Hi Kellie, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 11:44

Hi, it's my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Kelly 11:46

Yes, I am really excited to jump into talking about this book. I want to start by asking how you got started on this particular book. So you have a previous book, that's a, you know, Academic Press more of a traditional history. This book obviously has a lot of history in it. But it's not just a history book. So what got you started on this book?

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 12:08

I never intended to write this book. I was not I was not. I had a different book in mind. I was actually it was summer of 2020. I had written an op ed for The Atlantic that kind of went viral. And I got approached by a bunch of publishers like, "Is this a book? Is this a book?" And I was like, "Yeah, sure, yeah." But I was I was writing because I was mad, you know, I was frustrated, I was angry. I know, a lot of people felt quite similar in 2020. And then in the subsequent years, have since felt even more sort of outraged and depressed by the state of the world. And I wanted something that really spoke to that anger and spoke to that feeling. And so this book, really, is a result, which is why the book is, is history, because I'm a historian, but it's also a lot of personal family stories in there as well, because, because I understand that the work I do is both personal and political. And so I wanted to sort of blend genres in the sort of like theme of Beyonce a little bit and say, like, "You know what? Let's do a little bit of more than just history in here. Let's go deeper on some of these topics."

Kelly 13:29

So I want to ask about the importance of centering Black people, especially Black women, as actors in the story, not just as people that have atrocities passively, you know, forced upon them, but as, as actors, as central pieces of this story. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 13:48

That was so important for me. I mean, I when I when I start the book, I start out by telling the story about my great grandmother, Ernesta and I tell this really sort of tragic story in which she is nine years old, and she steps on a rusty nail and infection sets in and her mother takes her to see this white doctor, who instead of healing her offers a proposal that if he heals her in exchange, she has to work for his family and live with his family for the rest of her life. And my great, great great grandmother whose name I still don't know, refused that doctor's proposal. She picks up her ailing granddaughter takes her home and administers every natural remedy she can get her hands on and heals her granddaughter. Ernesta survives. And I didn't want to write a book about the doctor because I feel like we know that story. I wanted to write a book about my ancestor. I wanted to look at her refusal, her ability to say no, absolutely not, and carve out her own sort of path for her granddaughter that did not not include death or slavery. And so for me, putting women at the center of the story, and putting Black people at the center of their story is so important because I think that all throughout history, we've been given this really flat one dimensional perspective of Black people and Black leaders, that does not give the full texture and context of what they were up against, of what their courage cost them, of what was required to sort of overcome. Those stories to me have been too much at the at the margins, at the periphery. And so my goal was to say, "Let's put it at the center. Let's give them a mic. Let's crank up the volume. And, and really show why these stories matter."

Kelly 15:47

You say at some point in the book, "Refusal is Black culture," and then you frame the book around these, I think it's five different, five remedies, types of refusal. Could you talk a little bit about, you know, how you decided to structure it that way? Yeah. What that allows you to do to put different stories in conversation with each other?

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 16:10

So I started out thinking about the ways that we have been taught about resistance. And when typically, when we're, we talk about resistance, we talk about non violence, or violence, like those become the two options. And for me, non violence and violence wasn't at all expansive enough to really talk about the the myriad of ways that Black people have engaged in combating white supremacy. And so I wanted to look at these different remedies categories that Black people have taken up upon themselves, these tools, pathways, if you will. I look at revolution. I look at protection. I look at force. I look at flight, and I look at joy. And I think you could add a lot of different, you know, tools to this book, as well. But I focused on these because I think that they've been most central in my own research, but they've also been most central in my life, you know. I see joy as a weapon, I see joy as a way of really combating so much of the erosion that discrimination and oppression puts upon us. I see, flight as something that was very much a part of my own family's narrative, you know. I think about not just enslaved people running away during slavery, but I think about the Great Migration. I think about current Black travel right now, and how Black people want to move to Ghana, or they want to move, you know, out of the United States, or there's, you know, a common thread of Black people going to Paris. And so I thought about all of these different ways: protection, force, revolution, that people employ strategies, and how effective these strategies are. They really do transform key moments in history, because of Black activism and Black resistance and Black refusal. And so I hope people will build upon this work, you know, I hope people will identify other ways and remedies and strategies as well. But these five categories just felt so pronounced to me, I felt like I had to write a chapter about each of them.

Kelly 18:08

So the first one you talk about is revolution. And I'm going to be sitting with this for a while. You say that revolution is only revolution if it creates a better society for everyone. Yeah. And of course, by that definition, the American Revolution was not a revolution. Reconstruction had the potential to be, perhaps not realized. But like, Yeah, could you expand on that a little bit? I think obviously, the the example you give of the Haitian Revolution is so compelling, and so interesting to think about, as opposed to something like the American Revolution,

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 18:42

Yeah, revolutions, they really have to overturn systems, they have to replace broken systems with better ones with just ones. And when I think about the American Revolution, when I say it's not very revolutionary, I mean that because it doesn't change the lives for the better, certainly not for Black people, not for women, certainly not for Native Americans, not really for poor white people. In a lot of ways it replaces a distant ruler with the local one. And so there is not much that is revolutionary about the moment, unless you want to just talk of the creation of the United States as a as a newly formed country, but in power and practice, nothing particularly changes. But in the Haitian revolution, we see that one of the key motivations for the revolution was the abolition of the institution of slavery, that if we're going to create a new country, and they do, they create all first all Black nation in the Western Hemisphere. But they do that by specifically abolishing the institution of slavery. And so for me, the Haitian Revolution is a revolution. But also outside of the American Revolution, I see the Civil War as a revolution. I mean, the Civil War abolishes the institution of slavery and institutes reconstruction which doesn't take place anywhere else in the Atlantic world where you have formerly enslaved people becoming elected officials within less than a generation. So revolutionary change, I think when we talk about revolutions, I joke in the book that, you know, people think revolutions are like Armageddon and "We ride at dawn" and you know, you like really scary, apocalyptic end of the world collapse. And that's actually not true. Revolution is a rebirth of sorts. It's an equalizer, and it's forfeiture. It's forfeiture, particularly from people who are hoarding.

Kelly 20:34

So in the section on protection, you tell a history that I had not heard before, that seems so important. This is the Christiana Resistance. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about this story. It's it's one of those things. It's like the the point of this podcast right is like, "Well, wait, how didn't I know that? I thought I knew American history.

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 20:56

This story, the Christiana Resistance, it's also mentioned in "Enforcing Freedom" as well. It's a story I talk about a lot, because it's just so pivotal. And I think people often don't realize that during slavery, there was the Fugitive Slave Law, which basically allowed slave holders to go into the north, to go into places that were traditionally seen as safe havens, and to retrieve any person that had run away from them. And it didn't matter if they ran away, like five days ago, five years ago. It didn't even really matter if they were your property, if you could just lay claim to someone, you could essentially kidnap them and and bring them to the south to be to work as a slave. So I talk about William and Eliza Parker, who were both fugitives themselves, and had created within the community that they lived in, a border town in in Pennsylvania, the Black Self Protection Society, the Lancaster Black Self Protection Society. And this society basically committed that they would protect fugitive slaves, and they made their mantra, even at the risk of their own lives. And they do that very thing when one day four escaped slaves, four men, come to the Parkers' home, seeking refuge, they know of their reputation. And Eliza and William Parker, this is a no brainer, sure, come on, and they hide them in their attic. But because of that reputation within hours, the slave catchers, Edward Gorsuch, his son, his nephew, a US Marshal, a couple of other men, they show up to the Parkers' home and basically say, "We know you have our property, these four runaway slaves. We want them back right now." And William and Eliza Parker are like, "Over my dead body. It's not happening, it's not happening." And Eliza, to her credit, you know, goes to the to the attic of their home, starts to blow a horn to sound the alarm for the Lancaster Black Self Protection Society. She's being shot at at the window. Thankfully, the house is stone, and she still continues to blow the horn and to you know, basically rally the troops to come to their aid and assistance. Within moments, the house is surrounded by 80 Black men and women, ready to protect these four men. I think it's funny that Eliza's brother is terrified at the prospect of either being arrested or captured. And he says, "Yo, just give him up, let just let them go. It's not worth it." And Eliza picks up a corn cutter and says, "I will chop off the head of the first person that tries to give them up." And I'm like, "Oh, Eliza!" To me, I love the story, because it's like this corn cutter is not just for slave catchers. This corn cutter is for cowards, you know, this corn cutter, it's for anyone that would try to sell us out. And so, you know, long story short, no one knows who fires the first shot. But essentially, shots are fired, and Edward Gorsuch lays on the ground dying, the owner of these four men, he takes a beating from them. And as he lay on the ground dying, William Parker, who writes the account of this says, "And the women put it into him. The women put it into him," and I was like, "Oh my gosh!" I mean, the story is just incredible, because William Parker, and Eliza, they all have to go on the run, including the four escaped slaves. William and the four men make their way up to actually Frederick Douglass's house in Rochester, New York. He feeds them, he shelters them, he helps them get on a boat to Canada. And so while William Parker is in Canada, Eliza actually can't quite leave. They have three young children. She has to make sure that the children are with her mother and that they're safe. And as she tries to get to Canada, she actually gets captured several times and thrown in prison, escapes jail, you know, gets captured again escapes jail, and it takes her about three months to get to Canada. And we don't even know really the full tale of what it encompassed for her to, to break free and to get to freedom finally, but this heroic tale in which no one was prosecuted for the death of Edward Gorsuch, no one was held accountable. There is another sort of backstory to this in which I learned later that John Wilkes Booth was actually good friends with the Gorsuch family. And part of his sort of like, motivation for assassinating Lincoln and causing great violence was, you know, his feeling that no one was held accountable for the death of Edward Gorsuch. So it's really a story to me that sets off a lot of different historical moments, but also really affirms the idea that Black people were going to use force and protection and flight to save themselves and to save each other. And sometimes they were people they knew, and sometimes they were strangers. But that really wasn't the point. The point was to make sure that no one was enslaved. And yeah, that story to me is just always so gripping.

Kelly 26:06

And for the parents listening, they do reunite with their kids. Going ahead, I was like please, please, and I saw that, and I wrote in the margins, like "Thank God!"

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 26:18

Yeah, and their descendants are still alive to this day. So it is a happy ending for the for the Parker family.

Kelly 26:27

One of the other great stories that you tell us about the Black Panther Party, and you say in the book, and this is absolutely true, that they're so misunderstood in history. And the type of protection they were providing is not just the popular, you know, pictures people might think about with, like, machine guns or something, but it's actually a much deeper kind of protection. Can you talk about that?

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 26:50

Yes, I think, again, and I say this a lot, because it's just so true. We have very flattened one dimensional simplistic ideas around the Black Panther Party, and so much about Bistory, but the Black Panther Party in particular, I think, has not sort of been given the full coverage it deserves, especially when you think about the impact that they had in the community. You know, the Black Panthers found out very quickly, that guns were not going to be an effective strategy as part of their organization. It caused more violence than anything else. And when I say violence, I mean violence against them. And they, within a year of the Black Panther party organization, sort of put down the guns and say we need survival programs. And so they create one of their most famous programs is the free breakfast program. If your child gets a free lunch, or free breakfast today, that is a part and parcel of the work that the Black Panther parties that I know my children get in the state of Massachusetts, all children get free lunch. And, and that is part of their work, they created grocery stores and had grocery delivery and food drop off for people that, you know, did not have enough food to feed themselves. They had ambulance services, they opened up their own schools, they had tutoring programs, they had health clinics, you know, if you needed to get sickle cell testing, if you needed to get, you know, some sort of eye examination, they had eye doctors that would volunteer their time. I mean, they had prison visitation programs where you could go visit your loved one who was incarcerated upstate. They had voting campaigns and get out the vote campaigns. I mean, the list is really endless in terms of their impact. And what I say in the book that is so remarkable about the Black Panther Party is that they realized that the greatest offense and defense was actually not a weapon. Their greatest offense and defense was a fed, healthy, educated Black populace. That was the greatest threat to FBI, then Hoover and all of its COINTELPRO cronies was, "What do we do with an empowered, educated, healthy Black class? That's dangerous. That's a problem." And so I've talked about the Black Panthers and their efforts in this book as well.

Kelly 29:17

So you just mentioned that they realized that guns were not going to be the answer for them. But there are moments that you talked about in the history of times that guns were necessary, that, you know, guns were not just used against Black people, but that Black people were protecting themselves, defending themselves and their families and their communities with guns. And so you tell the story of Carrie Johnson in DC in 1919. I wonder if you could talk some about that. She is amazing.

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 29:51

So this is 1919, Washington DC, end of World War I, soldiers are coming home. Black soldiers are coming home as well. DC is sort of transforming, it's it's not quite Chocolate City yet or what we know of it much later. But you have this prosperous Black community in what is sort of like the quasi north/south. And you know, you have Howard University there you have the famous M school, you have a lot to be excited about. And in this moment when soldiers are returning, the summer of 1919 is also a summer of racial unrest all across the country. In places like Chicago and Arkansas, and in Texas, and in South Carolina, there are race riots taking place. And really, they are massacres. I mean, they are white mobs that are destroying Black communities homes, they're lynching Black people, they are shooting into Black people's homes and schools. And it is a terrifying time to live through one of these moments. And often it's not quite clear what causes them. But in the case of Washington, DC, it was an alleged rumor about a rape of a of a white woman by a Black man that really sets the city off. And for four days, and actually maybe about five days, Washington DC is in chaos. And it's during this moment, that Carrie Johnson, a 17 year old Black girl, she's at home with her father, and they live in a Black neighborhood, but their neighborhood is surrounded by white neighborhoods. And during this riot, white mobs start to attack these Black communities and they start to gather in the hundreds, and literally marched down the streets, throwing rocks into Black homes, shooting into Black homes. They're dragging Black people off street cars and beating them up. Carter G. Woodson talks about walking home from Howard University and seeing a Black man literally lynched and killed on the spot by a white mob in the middle of the day. You know, he's terrified as he's trying to get home. And Carrie looks out her window and she sees the mob coming up her block. And someone must have taught her how to use a gun. She goes up to the second floor of her home, she opens up the window and she starts to take potshots at the mob, at the oncoming mob. And you know, I can't imagine being 17 year old and watching hundreds of people marched down the street to terrorize you and thinking this is the best I can do to try to help out my community. Well, people in the community, white people, see her and they notify the police. Now again, the police is there not to protect Black people and Black property, but to really sort of serve as a witness to the mob and the mob says to them, you know, there's there's someone in this window, they're taking shots at us. There's someone in this house, you need to check out that house. And so the cops go over to Carrie's home. At this point, Carrie and her father are hiding on the second floor in her bedroom underneath the bed. And the cops knocked down the door. They don't identify themselves, the house is pitch black, they quietly head up the stairs, open the door to her bedroom. And that is when all hell breaks loose. You know, Carrie starts shooting, the cops are shooting off of the walls and everywhere because it's dark and they don't know where the gunfire is coming from. Officer Harry Wilson takes two shots. Carrie gets shot in her thigh, her father is shot in his shoulder. And when it's all said and done, Officer Harry Wilson is on the floor dead. And he is shot and killed by Carrie's gun. And you know, Carrie and her father are pulled from under the bed. They're marched down to the street, they're arrested, an ambulance is called. And it's clear because you know there are witnesses that understand that Carrie is the person that did this, that she's the 17 year old girl that killed this cop. And at that moment, I was like, "Uh, she's going to be lynched on the spot." That is what I thought before I could, you know, get to the end of the story. And in that moment, it also starts to pour, like it starts to rain and pour like torrential downpour. And that is actually what stops the mob. You know, Wilson is president but he sends in the troops later he sends him like 2000 troops to sort of shut it all down. But the rain is what really caused the mob to halt, which is interesting that rain can do that. But Carrie is arrested and she is charged with first degree murder. And I don't know if I want to say what happens to her. I think I want to save that for readers to sort of find out on their own or you can Google it, whatever. But what to me is most fascinating aside from the outcome of Carrie's life is that the support she receives for trying to protect her community and using force against an a white angry mob and being a young teenaged girl at that, you know, there are funds sent for her legal counsel, people are praising her as a hero, and as brave, there's a poem written by her about her by an 11 year old girl who talks about, you know, soldiers coming back to fight. And she talks about how Carrie was brave and keen. And, you know, this is also a moment where it's sort of the height of like, respectability politics, you know, young girls are supposed to be seen in a certain kind of way, and shooting a police officer, it's not something that people would praise. But people did that. They hailed her. And they wanted to protect her in the same way that Carrie wanted to protect her community. And never have ever read a story about a Black girl doing such a thing, and, and being praised for it as well.

Kelly 35:53

So your last section, you write about Black joy, and you talk about how joy and grief interact. And I wonder if you could talk you, you talk a lot about your own personal story, your family's story in that section. I wonder if you could talk both about Black joy in general, but also what it felt like as a historian to be writing something so personal.

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 36:17

Oh man. Yeah, I had a lot of feelings writing this chapter. Because at first I was so excited to write about joy, because I was like," Yes, this is gonna be the best chapter. It's gonna be the most fun to write." And then when I started out the chapter, I was like, "This is not how I thought I'd feel writing this chapter." I write about my siblings' death. And so I'm, I'm, I come from a big family. I'm one of seven, and six girls, one boy. And in 2007, my sister had been diagnosed with breast cancer in 2005, but she passed away in 2007, after a rough battle with breast cancer. And while we were shocked by her death, because she had been sick for so long, I think that we had been slowly sort of preparing ourselves for it. And she passed away the day before Thanksgiving, really sort of like Thanksgiving morning. And we all attended her funeral. And my brother spoke at her funeral. And my brother and sister, my sister Tracy, and my brother, William are both ministers. And when my brother was speaking at her funeral, he was talking about the difference between joy and happiness and how joy is sustaining while happiness is fleeting, and how we ought to hold on to joy. It was just really such an encouraging word that all of us needed to hear in that moment. And we laid my sister to rest, and we all flew back home to our destinations. And within a day, my mother called me and said, you know, William's in the hospital, and the doctors are saying it doesn't look good. And I was I hadn't even unpacked so I didn't even know what to make of that. He had said that he couldn't breathe. And what he had was pneumococcus, which is a viral infection that can be extremely deadly, especially for people that have had bone marrow transplants, and my brother had sickle cell anemia, was born with sickle cell anemia. And when he was 16, he had a bone marrow transplant. And so while he was cured of sickle cell, he was still susceptible to these viruses. And within three days, he was gone. And in about a 10 day period, a two week period, we had lost two of our siblings, my second to oldest sister, and my only brother. And we were just, I mean, there are no words to really talk about that kind of compounding loss. And it all happened right before the holidays. And so I write about in the book, how we were just zombies. And I also talked about how grief is really love. And that when we love our spouses, and when we love our children, and when we love our, you know, siblings, that that love doesn't, doesn't go away and that and that we can find sort of healing for ourselves and my family has has healed, I would say from the loss. But I'm grateful that I can look back on their lives and have a lot of joy. And so I talked about like, how joy really comes from a place of loss, how joy is understood best in struggle, and it's understood best in trying times, and it's what to what fortifies you and so, and laughter really got us through a lot of the grief as well. And so I talk about, there's funny stories in that chapter. There's funny stories and in joy as well. But I think that Black people use humor and laughter and love and community as a balm, not just as a weapon against white supremacy, but really as a as a remedy, for sort of addressing so much of the pain, and the hardship that comes with, you know, racism. So it's a kind of ironic chapter in some sense, in that you're talking about joy and really sad, tough things all at the same time. But I also think it's something that people understand very well. I mean, the pandemic itself was something that was grievous, we lost over a million Americans. And yet, there are also aspects of the pandemic that are hilarious when you think about culturally, like how we were navigating this new normal, that also brings levity to just these tough situations.

Kelly 40:42

There is so much more in the book that we're not going to get to including you talk about one of my very favorite people in the world, Ida B. Wells, so she shows up in the book. So can you tell listeners how to get both the book and the merchandise?

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 40:57

Yes, yeah. So the book you can get anywhere books are sold, which is great. I love supporting independent bookstores. So if you choose to do so, find your favorite bookstore and support them. If you don't like to read, but you do like to listen, there will be an audiobook, and I narrated the audiobook as well. So I hope people will check that out. And yeah, you can go to my website, KellieCarterJackson.com/store. And I have like, "We Refuse" merch, T shirts, mugs, hats, all that good stuff. It's Kellie with an IE, and I'm just I'm really excited that the book is out in the world, and that people are being really receptive to it. I think we're in a moment right now, where refusal is just so important. And so anywhere we can, you know, sort of get access to better tools and strategies and ideas about how we can combat some of like, the biggest evils in this world, I'm all for it.

Kelly 41:53

Yeah, and I really want to encourage white listeners to read the book and to really sit with it to like, not get defensive. Not there, you know, there, there are moments where it's gonna be a little bit of a natural reaction to like, just like let yourself feel those feelings and really read and, and understand and feel the book, I think is really important.

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 42:17

I hope people will. I mean, I tried to be very clear in the book, like there is a difference between white people and whiteness and white supremacy. I'm looking at whiteness and white supremacy as the power that causes violence and wreaks harm and havoc. And I think we can separate those sorts of two ideas. But yeah, I will say I was very clear in the preface. I was like, "This is not a DIY three point plan on how we solve racism in three neat steps." That's like, no, that's not what this is. It's it's, there's it's biting. But I think that that even that tone is refreshing.

Kelly 42:56

Yes, absolutely agree. Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 43:01

No, this this was wonderful. It was a pleasure to be able to share what's in the book, and I hope that more people read it and resonate with it. And that's, that's all you can ever want for as a writer is to be read.

Kelly 43:15

Yeah. Well, Kellie, thank you so much for speaking with me and for writing this incredible book.

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson 43:20

Thank you, my pleasure.

Teddy 43:49

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Kellie Carter Jackson

Kellie Carter Jackson is the Michael and Denise ‘68 Associate Professor of Africana Studies and the Chair of the Africana Studies Department Wellesley College. She is the author of the award winning book, Force & Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence was a finalist for the Frederick Douglass Book Prize, a winner of the James H. Broussard Best First Book Prize, and a finalist for the Museum of African American History (MAAH) Stone Book Prize Award for 2019. The Washington Post listed Force and Freedom as one of 13 books to read on African American history. Her interview, “A History of Violent Protest” on Slate’s What’s Next podcast was listed as one of the best of 2020. She has also given a Tedx talk on “Why Black Abolitionists Matter.”

Her essays have been published in The New York Times, Washington Post, The Atlantic, The Guardian, The Los Angeles Times, The Nation, the Boston Globe, CNN, and a host of other outlets. She has been featured in numerous documentaries for Netflix (African Queens: Njinga and Stamped From the Beginning), PBS, MSNBC, CNN, and AppleTV’s “Lincoln’s Dilemma.” She has also been interviewed on Good Morning America, CBS Mornings, MSNBC, Democracy Now, SkyNews (UK) Time, Vox, The Huff Post, the BBC, Boston Public Radio, Al Jazeera International, Slate, and countless podcasts.

Carter Jackson loves a good podcast and her Radiotopia family! She is Executive Producer and Host of the award winning “You Get a Podcast! The Study of the Queen of Talk,” formerly known as “Oprahdemics” with co-host Leah Wright Rigueur a… Read More