Pullman Porters & the History of the Black Working Class

In the early 20th century, career options for Black workers were limited, and the jobs often came with low pay and poor conditions. Ironically, because they were concentrated in certain jobs, Black workers sometimes monopolized those jobs and had collective power to demand better conditions and higher pay. The Pullman Company, founded in 1862, hired only Black men to serve as porters on Pullman cars, since George M. Pullman thought that formerly enslaved men would know how to be good, invisible servants and that they would work for low wages. In 1925, the Pullman Porters formed their own union, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, with A. Philip Randolph serving as president. After years of struggle, in 1935, the Pullman Company finally recognized the union, and it was granted a charter by the American Federation of Labor (AFL), making the Brotherhood the first Black union it accepted.

Joining me in this episode to help us learn about the Black working class is historian Dr. Blair L. M. Kelley, the Joel R. Williamson Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and the incoming director of the Center for the Study of the American South and author of Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class.

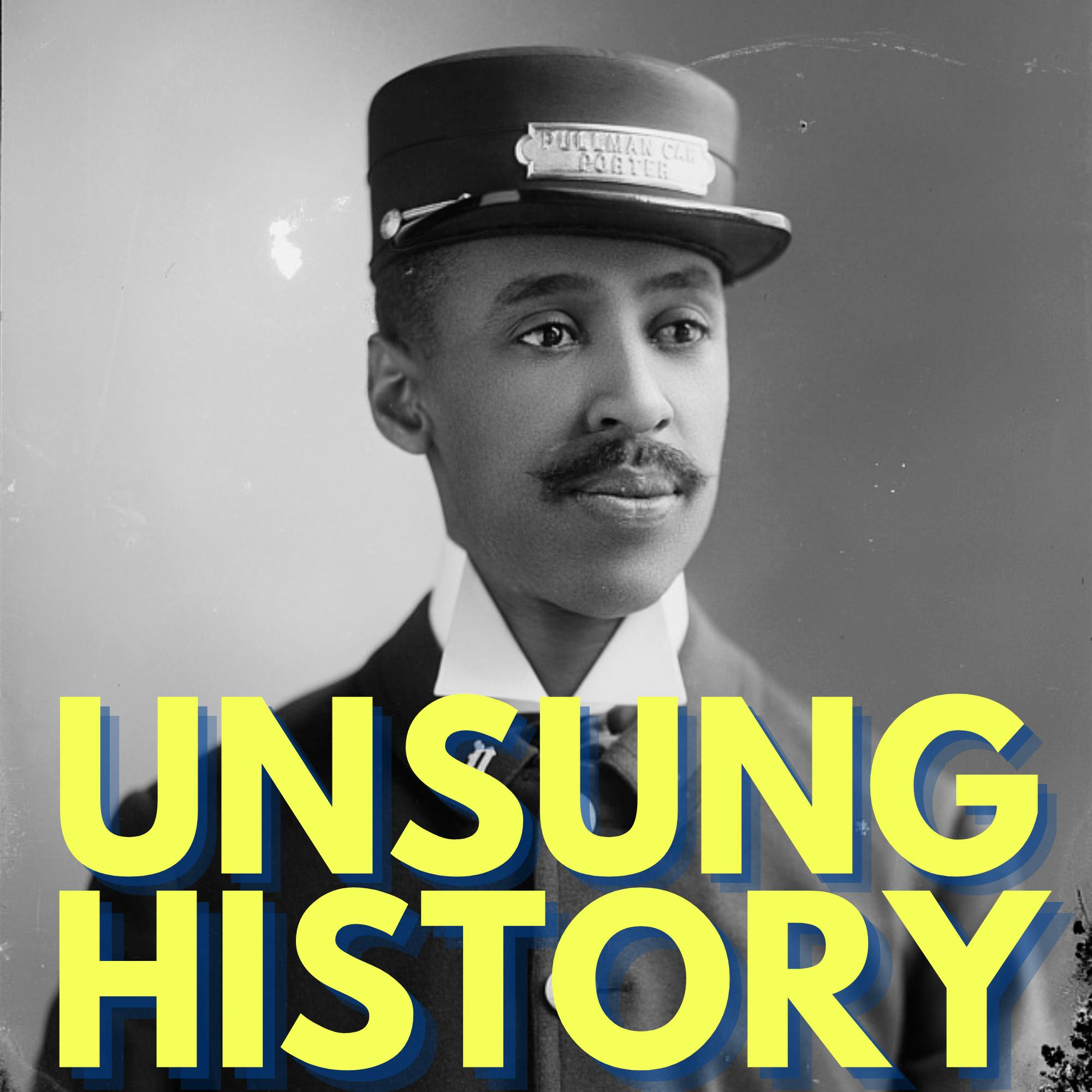

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “Pullman Porter Blues,” music and lyrics by Clifford Ulrich and Burton Hamilton; performed by Clarence Williams on September 30, 1921; the recording is in the public domain.The episode image is: “J.W. Mays, Pullman car porter,” photographed by C.M. Bell, 1894; the photograph is in the public domain and available via the Library of Congress.

Additional Sources:

- “George Pullman: His Impact on the Railroad Industry, Labor, and American Life in the Nineteenth Century,” by Rosanne Lichatin,” History Resources, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

- “The Rise and Fall of the Sleeping Car King,” by Jack Kelly, Smithsonian Magazine, January 11, 2019.

- “The Pullman Strike, by Richard Schneirov, Northern Illinois University Digital Library.

- “Pullman Porters,” History.com, Originally published February 11, 2019, and updated October 8, 2021.

- “The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters,” by Brittany Hutchinson, Chicago History Museum.

- “Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (1925-1978),” by Daren Salter, BlackPast, November 24, 2007.

- “A. Philip Randolph Was Once “the Most Dangerous Negro in America,” by Peter Dreier, Jacobin, January 31, 2023.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers, to listen too. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified on December 6, 1865, formally outlawed slavery in the United States and its territories, except in punishment for crime. However, it wasn't until 99 years later, when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on July 2 of that year, that discrimination in hiring on the basis of race was outlawed in private employment. After the Civil War, while Black people in the United States were no longer enslaved, they were often limited in the employment they could find, and could be subjected to terrible working conditions and poor pay. Ironically, because they were concentrated in certain jobs, Black workers sometimes monopolized those jobs, and had collective power to demand better conditions and higher pay. I'm going to zoom in now on one such instance, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and then zoom back out to the larger story of the Black working class, in my conversation with today's guest. In 1862, George Mortimer Pullman founded the Pullman Company to manufacture luxury railroad cars with sleeping berths that included drapes, carpeting, along with Pullman's signature customer service. At its peak, 26 million people a year rode in Pullman cars. By 1884, Pullman had created a town for his growing workforce on 4000 acres between Lake Calumet and the Illinois Central Rail Line, south of Chicago. In response to the economic depression of 1893, Pullman cut wages 25%, but kept rents high in the company town, leading the workers to strike. After a federal injunction, President Grover Cleveland sent in federal troops, leading to violence, and eventually, the strike ended with Pullman rehiring the workers, as long as they signed a pledge never to join a union. The factory workers weren't the only employees that Pullman mistreated. In order to provide the famed customer service on Pullman cars, each time a railroad leased a Pullman car, a porter came with it. For this role, which included such tasks as setting up the sleeping berths, loading baggage, and serving passengers, Pullman hired only Black men, often from the south, with his stated expectation that formerly enslaved men would know how to be good, invisible servants, and would be willing to work for low pay. Despite the poor pay that Pullman provided, many Black men eagerly accepted the work, unable to find employment elsewhere. At one point in the early 20th century, Pullman was the largest single employer of Black men in the United States, with 12,000 porters. The wages that Pullman porters earned, which in 1926 averaged about $810 a year, or $14,000 a year in today's dollars, were envied by others in the Black community; but they didn't come close to making up for the 400 hours per month that Pullman porters were expected to work, nor the treatment by passengers, who called them, "Boy" or "George." In the early 20th century, most Pullman workers were represented by the American Railway Union, but the union refused to include Black workers, including the porters. On August 25, 1925, the porters formed their own union, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, led by A. Philip Randolph, a labor organizer, and publisher of, "The Messenger," an independent magazine that had ties in its founding to the Socialist Party. Because Randolph himself was not a porter, he didn't risk being fired by Pullman. The Brotherhood worked to enroll Pullman porters into the union, but the Pullman Company refused to recognize the union, and responded to the union's efforts by firing union members and threatening to fire others who might join. In September, 1927, the Brotherhood attempted to secure a federal investigation into their conditions, filing a case with the Interstate Commerce Commission, but the ICC ruled that it didn't have jurisdiction in the matter. By 1928, it seemed that threatening a strike may be the only way to gain recognition, but even then, the National Mediation Board, established by the Watson Parker Railway Labor Act of 1926, refused to act on behalf of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, having been convinced by the Pullman Company that the union couldn't actually pull off a strike that would threaten the sleeping car service. The Brotherhood backed down from their planned walkout once they were faced with the threat of replacement workers. After Franklin D. Roosevelt became president, though, the Railway Labor Act was amended in 1934, and porters were granted new rights, which encouraged more porters to join the Brotherhood. In 1935, the Pullman Company finally agreed to recognize the union, and the Brotherhood was also granted a charter to the American Federation of Labor, AFL, making the Brotherhood the first Black union it accepted. In 1937, the Pullman Company signed a contract with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, giving the porters raises, a shorter workweek, and overtime pay.

A. Philip Randolph wasn't done fighting for Black workers, though. In 1941, he organized the porters, along with the NAACP and the Union League, and said that he would bring 100,000 Black people to march on Washington if President Roosevelt didn't end racial discrimination in employment in the defense industries. Despite his initial reluctance, Roosevelt relented, signing Executive Order 8802 into law on June 25, 1941. On August 28, 1963, Randolph did lead a march in Washington, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, with 250,000 participants. Although Martin Luther King's speech is the best known from that day, Randolph's speech preceded his, where he said, "Let the nation and the world know the meaning of our numbers. We are not a pressure group. We are not an organization or a group of organizations. We are not a mob. We are the advanced guard of a massive moral revolution for jobs and freedom." Joining me now, to help us learn about the Black working class is historian Dr. Blair LM Kelley, the Joel R. Williamson Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, and the incoming director of the Center for the Study of the American South, and author of, "Black Folk: the Roots of the Black Working Class."

Hi, Blair, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 10:53

Thanks for having me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 10:55

Yeah, I really love this book. So I'm excited to speak with you about it. I want to hear a little bit about your inspiration in writing it?

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 11:03

Well, I mean, it's interesting. They approached me about the possibility of writing about the Black working class. And at first I was like, "Well, that's not exactly what I do. I'm a historian of the African American experience in general. I'm a historian of movements." And I was intimidated, because oftentimes, labor histories really have a different kind of tone than I write with. And so I thought to myself, "Well, you know, this might not be the right fit." And so they said to me, my editor and my agent, you know, "Let's just start proposing. What would you write if you could write your own history of the Black working class?" And so I started crafting a proposal that really started with my family, and the stories that my mother told me, that my father told me, that my grandparents shared with me when I was growing up, and those stories, gave me that framework. And then I tapped into the the kinds of jobs that I teach about when I teach about African American history, and the jobs that I felt were really transformative in terms of establishing the character of the Black working class over time. And so I came up with a set of things that I think look different than the standard labor history, but really reflect what I was interested in and what I really felt were the roots of the Black working class in history.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:35

Could you talk a little bit about the title? You talked about this a little bit at the beginning of your book, and I wonder if you could talk about it? Because I'm sure, as you mentioned, in the book, people will hear "Black Folk," and might think about WEB DuBois, you know, but that that's not what you're referencing here. So what why did you title it "Black Folk?"

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 12:52

So for me, that was another interesting moment. I had finished the book, and my editor was like, "Well, when are we going to address the elephant in the room?" And I'm like, "What is that? What elephant are we talking about?" And he said, "Well, you know that you are inspired by DuBois', 'The Souls of Black Folk,' and that's why you titled the book that way." And I was like, "Oh, no, that at all what I was thinking," and so for me, when Black people talk about each other, and the sort of the everyday version of us is Black folk. Black folk show up in a certain kind of lexicon that I wanted that comfort, that familiarity, that that every day experience to be reflected. And so for me, Black folk is just the way we refer to each other. It's how I think of myself, it's how I think of my ancestors. And so DuBois, you know, came to writing "Souls of Black Folk," I think, in a bit more of an anthropological kind of lens. And I strive not to have that, in this work, really more of a way of knowing, grounded in my own experiences.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:06

So you mentioned that you come to this from, you know, thinking about your, your family, and the stories that you heard. And so you tell the stories of some of your family members, but you also tell stories of other individuals in this book, not just your family members. Yes. And that's not all you do, of course, that you know, there's also a little more of the sort of traditional labor history. But can you talk a little bit about why you structure the book in that way, and why you're telling stories of individuals?

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 14:34

So I'm an oral historian. It's really the first work I did as a historian. I was part of a project called, "Behind the Veil" at Duke University, in graduate school, and I went out into the field and did interviews. And so I did that before I even took a history class of any sort in grad school. And so it's very formative to how I think and how I want the voices of the past to really tell us what those experiences are like and I think oral history is such a rich opportunity to fill in those gaps. And so I not only used my own family stories, as you said, but I used, I use a oral history from "Behind the Veil," I use some other ones that I found that were really amazing with particular folks who I thought moved the story forward and narrated into the spaces that sometimes we don't know, from just looking at traditional archival records, or union records. And they really provided a richness of tone and outlook and the detail about everyday experience that I, I wanted to add in. And so I wanted to write them, just like they were my family members. And so I tried to provide that same kind of rich texture, I made family trees for everybody, I have 26 family trees in my ancestry account. And you know, it's much harder to make a family tree for somebody who you don't know that well. But some of them are really good trees. And I provide I shared those trees with the some of the family members of the people who I'm using as my subjects in "Black Folk." So I really want that sort of personal ancestral information to be another way of knowing on top of the archival.

Kelly Therese Pollock 16:24

So one of the sources for oral history that people are probably aware of is the Works Progress Administration. And so one of the sources you use, this washerwoman, Sarah, is interviewed. But you point out, in addition to the interesting things that you can get from that interview, that, that it's really shaped by the interviewer, by this woman, this white woman who is who is coming down. Can you talk a little bit about that? And you know, and especially with your work in oral history, how the, the historian who's asking the questions, shapes the the stories that we hear?

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 16:59

Yeah, when I teach oral history, I always teach the WPA interviews just for precisely this reason, that the WPA interviews were a power imbalance. Oftentimes, in the midst of segregation in southern cities and southern rural places, white interviewers are coming to Black people's houses, which is a non traditional kind of thing. And so when they enter, they have a lot of clout over them. And so the interviewers don't feel at all like they need to pull back or provide any sort of space for their Black interviewees, and interviewees don't have much power to do anything, but go along, or at least appear to go along with those interviews. And so I could see that tension in the text of the interview that I use with Sarah Hill, and the things that she was leaving out, and or not really diving into that I could see in the her census record, the loss of a son, for example, that she doesn't mention. And, and I can see her discomfort, you know, her physical discomfort and, you know, trying to make sure that this this white stranger is cared for in her yard. So I wanted to write through their perspectives. I wanted to think through what "washerwoman" meant, both to a white observer, and to a person experiencing it as a field and the empowerment that she got from it, in terms of her own life. And so it was a fun kind of exercise to write through, you know. As I was working on it, people were like, "Well, why are you doing this?" But for me, it was, it was important to not only say that there's a power imbalance, but to really explore it a bit.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:09

I want to use the story of the washerwoman to talk about skilled labor and quote unquote, unskilled labor. So we're speaking just a few days after this new Florida guidelines or something about like, how they're going to teach about Black history and, and this terrible idea that, you know, we should be saying that enslaved people gained skills in their enslavement. And yet those same people, after emancipation, were told, "You have no skills. You can only do unskilled labor." So can you talk a little bit about the ways you know, the the washerwomen are a great example that that this labor is highly skilled. It's not at all unskilled, but yet it's being treated as and paid as unskilled quote, unquote, unskilled labor.

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 19:36

Yeah, the dynamic that I you know, stands out for me between the unskilled and the skilled as I was working on this, you know, that's the traditional sort of historical framework that we put on labor categories and so you know, there's skilled and unskilled so that you know, that's how I was taught. And as I was working on this, I was like, "Wait, these these women made their own soap. They built their own wash pots and, you know, refuse fire, like, you know, they're doing all the kinds of things that we think are valuable now, right, you know this, like artisan soap, and, and you know recycling other kinds of materials for reuse. They're making their own starch. They're making their own materials to raise stains, from organic things." Whoa, I, if you left me with a, you know, a pile of organic materials and said, "Now wash your clothes," I would be in a bad, bad way because those things weren't passed down to me. And so for me, that's when I was like, "Okay, let's do skilled work to really know how to do this successfully." I remember my mother talking about, you know, seeing her aunt do laundry. And you know that it was an iron that the reason that we call it an iron is because it was a piece of iron, where you would have to wrap some kind of rag around the handle to make it tolerable enough for you to not burn your hand, but hot enough that you could smooth clothes, pre polyester. And it was just, you know, really powerful to me to think about. Well, all labor has some set of skills built into it. I was watching on Twitter, my at the time faith. And the farm workers union, were creating these beautiful reels of farm workers harvesting different kinds of foods. And the one that stood out to me the most were radishes. And they were cutting the radish and pulling them out of the ground, cutting them and bundling them in like a motion. And the little bundle that we buy in the supermarket was like perfectly made after a few seconds, under this man's directive and care. And I was like, "Well, that's unskilled labor." You know, if we, if we go back to, you know, historians, and sociologists and labor economists, that's unskilled labor, but the rest of us would probably, you know, cut ourselves in the attempt to do it, and it would not be perfectly bound and the right size and so quick. And so it was just a reminder to me to slow down and think about the labor that people did, the knowledge they brought to it, the skill, the professionalism, and to really describe it, and sit with it and honor it.

Kelly Therese Pollock 22:31

So this leads also then to really a labor movement, to solidarity among workers. And so I thought it was so interesting several times in the washerwomen, in the domestic help, in the Pullman porters, that that you see that these people are forced into this kind of work because of segregation of the labor market, that they have no real other choices, but because they are forced into that and they are the only ones doing this work, they have a certain power, because they have a monopoly on that kind of labor. So could you talk a little bit about that, that dynamic and the way that the the people you're talking about who are who are not necessarily the people we think of when we think about like labor unions and labor movements, but are such an integral part of the history of labor movements in this country?

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 23:22

Absolutely. So for me, you know, both the washerwomen and the Pullman porters are just, and the postal workers that I write about, are such tremendous examples of the power that Black workers can have to wedge their circumstances against their desired goals, and a reminder that, you know, oftentimes we are taught that labor organizers must come and raise the consciousness of workers, and help them understand their positionality, and then, you know, organize them into unions. And here, you see people who are emancipated. Washerwomen began to organize the first union in 1865 in Jackson, Mississippi. They were enslaved, and then they were free, and they understood, "Hey, we have a monopoly on this work. This work is stigmatized. White women will never really want to do this en masse. And if you want us to do it, we're going to do it the way we want to do it. We're going to do it our own homes, we're going to watch our own children, as enslaved women, we could not. We're going to demand a living wage. And we're going to make sure that we're all doing this collectively." And so they didn't need their consciousness raised. Their consciousness was built in enslavement. The Pullman porters understood that if George Mortimer Pullman created an all Black male labor force, in most of the country, boy, they had each other and they could build on that community solidarity. And they could use the rails to advance the cause of African Americans in general, and they could use it to build a union, that was tremendously strong, and the most important union, in probably African American history. That leads to directly to the civil rights movement. So there's just such a tremendous body of knowledge in these communities of workers, that was impressive.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:21

I want to talk a little bit about the south. So the south is kind of this other character. You know, so a lot of these families start in the south and then move north, but they never forget that they're from the south. Your family never forgets the roots in the south and, you know, literal roots, right? Because we're talking about sometimes about like food that they're growing, sweet potatoes and things. Yeah. So can you talk a little bit about that maybe just from your own family's perspective, of the the importance of, of remembering where you come from, in the south, you know, even I think you were born in the north, yourself. But you know, you still remember that, you know, the family ties to the south, and then you returned to the south. So can you talk a little bit about that?

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 26:14

I think it's an interesting dynamic, because, you know, when we teach the migration, oftentimes, we're teaching like, people had to evacuate, they had to leave, you know, very quickly, and they do know, my family absolutely, had to flee. And the choices that they had, were, they were very slim. And it really was about survival and leaving, but in leaving, they didn't become different people. The things that they valued, their sense of land, and as you said, food and culture and faith, were all grounded in the experiences they had as southern people. And so as much as you know, they're living in Philadelphia, in our case, you know, they're very, you know, my grandfather was from Georgia. Like, if you heard him and saw him, you didn't really think much about Philadelphia. You really think about Georgia, and my grandmother was from South Carolina, and she, you know, she's like, "Oh, you're a Geechee girl. When I make this rice, you, you love it so much." And so she wanted me to, to be connected to the place where she was born. And, you know, they, they wanted me to understand it and wanted me to, to eat like it and think like it and, and to honor it and respect it and not to be ashamed of where we were from. And so it's a big part of who I am as a person. So I've, you know, been in North Carolina a really long time, most of my adult life. And, you know, North Carolinians are never going to consider you to be from here unless you were born, like in their neighborhood, like they know, if all the people so I don't know that I can become a southerner again, but I certainly am a kind of southerner, and then part of an interesting, Black southern diaspora that is returning back. And so it is really profound the degree to which my upbringing is a reflection of all the communities where they were from.

Kelly Therese Pollock 28:14

I want to ask, while we're talking about your family about, you know, you talked about the stories and the things that you heard about the things that they didn't talk about, you know. So you talked about your I think it's your grandmother who, who worked for 10 years as a maid, but that wasn't something she talked about, and about all of the the loss that they suffered, and those were things that they were not necessarily sharing with you. Can you talk a little bit about that the sort of the pieces that are missing in those family stories and the things that, you know, you learned along the way or maybe you learned some of in in actually doing this research?

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 28:50

Yeah, absolutely. I think my grandmother was very proud of her work at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. In the first generation, when she first migrated, she couldn't get a job there. They weren't hiring Black women. And she had a high school education, she was ready to do that work. And she had to be a live-in, household laborer, and to be away from my mother for most of the week, and to have another woman raise my mom when she was really little, because she wasn't yet school age. And so it was a profound loss for her and a shame for her. My mother, I tell the story in the book about my mother, having to board a streetcar and ride from where her mother worked back to her neighborhood by herself before she could read and see the street signs. And my mother told me that story a long time ago, well before she told me that my grandmother was a maid. And so when I started to click it all together, it became even more poignant that it wasn't just that my grandmother just had some weird thing going on. She literally wasn't allowed to take her own daughter home. And so it just, you know, those poignant moments that I did get to finally talk to my mom about, before she passed away, were really something else. But there were other things that I discovered in doing census research that my grandmother had a sister and a brother in law and a niece and nephew who passed away from tuberculosis that I never knew any of that. I don't even know who in my family may have known about the existence of this whole other sibling. And so it's just very powerful, the suffering that that generation experienced, and yet, was there to give the sustenance to me as best they could, in spite of what they lost and what they suffered.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:48

You just mentioned the sister and brother in law, and their children, and they died of tuberculosis. And yeah, you know, it's striking how how, for the the Black working class, there is this, this intersectionality, right, of not just poor working class conditions, but then also marginalized communities often with terrible conditions. Like, can you talk a little bit about that, because that that has not stopped, right? Despite the fact that health care in this country has gotten better? And all of those, it's still disproportionately working class Black people who are affected by things like COVID-19. So Can can you talk a little bit about that? And that piece of what we should be thinking about when we're thinking about the Black working class?

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 31:33

Absolutely, it was really poignant for me, because, you know, I was writing this in the midst of COVID. And, you know, not even fully having a tight grasp on exactly what it meant, as I was working on this research. But the echoes that I began to see with the history of a Black working class that suffer from higher levels of disease, live in more exposed areas for carcinogens in the air, and the water and in the soil, who always are disproportionately suffering from, you know, a health gap that is intergenerational at this point. And COVID just brought that home again. It was really profound to to make sure that I thought about those, those consequences and those real live burdens that the working poor, have carried and continue to carry, particularly as you know, we all were like, "Oh, we have to stay home stay safe." And there were so many of my brothers and sisters and community with me who were like, "I was never home. I was always essential. And I was always at the hospital or supermarket or delivering the mail." And so that really sort of ethic of care that had to come into play for them, they had to take care of each other and figure things out on their own, before we had good answers. And they had to find ways to try and survive. And we know that you know, there was a disproportionate toll that COVID took on the Black working class and working class people in general, in this time period. So it was it was really an important lesson that was echoing in our, our present moment that I had to bring to bear in this story.

Kelly Therese Pollock 33:27

Yeah, so actually, I want to follow up on that, that ethic of care, because I think one of the things that you talk about so powerfully in this book is the the communal nature, the the communities around the Black working class. And you know, you talked about it when you were talking about like Black folk and the way that you titled the book, but I think that's so important to then understanding things like the labor movement that comes out of this, and then the civil rights movement that that comes out of that. So could you talk a little bit about that, that community, that communal spirit that really connects all of the stories in this book?

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 34:03

Yeah, I started "Black Folk" with enslavement, and with the forebear of my grandfather's, Henry, who was the farthest person I could find on his family line. And it's unusual to talk about slavery in sort of working class history, because, you know, not good Marxian theory, right? It shouldn't be talking about enslaved people. But for me, what was important there was to talk about the roots of that community, and that the ethic of care that I see in the 20th century is grounded in the survival of the enslaved, that they have to remake community, remake family, to redefine care, redefine how they all will take care for each other and look out for one another. And that the folks who come out of enslavement, build a different kind of vision of the world, and that their American Vision is fundamentally not survival of the fittest, the individual, bootstrap lifting person. But really, how do we do this together? And how do we survive together? And how do we tell each other, the best way to go forward, and that comes from enslavement and it's carried forward. It is the inheritance of the future generations from the enslaved. They don't have much given to them at the end of enslavement, but they do have that sense of who they are, and how they have to care for one another. And so for me, that was a powerful thing to see that, you know, the Pullman porters aren't organizing by themselves. There are men and women who are not Pullman porters who are organizing, giving funds, providing support, cheering them on in every way, shape, and form. And when the Pullman porters get recognition in 1937, federal recognition for the first time, it turned right back around, and they demand that the desegregation of defense jobs from the federal government, they had nothing to do with them as a union. But it's that sense that the broader fight is everybody's fight. And that was what was so powerful for me to see again, and again, and again.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:24

I really appreciated how much you drew out the stories of Black women in this too. I think, you know, it's it's easy to think of working class and think of, you know, white like, that's what we're told by media over and over again right now. And then it's very easy to think of labor history and think of men and men's stories. So could you talk a little bit about that your choices to really include and highlight Black women's stories in this book,

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 36:54

I think, you know, they're underwritten, this whole histories of the Black working class where you can look for the term laundress or washerwoman, you can look for the word maid or household worker, and they really won't be there in the index. So I found that to be horrifying, because if we want to understand the processes by which this whole community is able to survive, migration is able to move these movements forward over time, women are essential to the way, Black women are, you know, the prototype of women workers in the United States. And they really do deserve study and deserve extended attention. And when you study them, you know, I discovered things that I don't think I learned anywhere else. I, I had no idea that the number of Black women in household employment actually increases in the beginning of the 20th century. You would think it would be quite high in the 19th century, but no, it shoots up. And it shoots up around the time that of the Second World War, when white women are asked to go into factories and do factory work, because their, their men are abroad. And Black women go into white households at that time to watch the children of the women who are called into defense employment. They're paid much better than the jobs that they are taking, jobs that were not open to them, for the most part. And so, you know, it was powerful for me to think, "Oh, well, Rosie the Riveter, our, you know, our icon of white women working, has a Black maid, and is you know, undergirded by Black women's labor." And it was powerful for me to think about the ways in which Black women's migration really does fuel, all of these other movements that we were talking about and thinking about, that washerwomen are so strategic and brilliant is something I've known for a really long time, in part because of the amazing work of Tera Hunter and her book, "To 'Joy My Freedom," which I just adore. But that the model that she outlines of what happens in Atlanta in 1881 is replicated on a smaller scale all over the entire south and parts of the country all over, that washerwomen are so organized, and so determined, and really do change the shape of what's possible within segregated communities. And with with limited pay and limited opportunity, they make a whole world for themselves. And so that was really powerful to have women's history be those opening doors of new lessons for just how profound their impact was.

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:41

Well, everyone should go read this book, and one of my personal heroes shows up several times, Ida B. Wells Barnett.

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 39:47

Oh, come on now.

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:49

We didn't even have time to go into her. So tell everyone how they can get a copy of the book.

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 39:54

Well, the book is everywhere. If you you know, go buy it from your local bookseller because I love to support our local bookstore. I think they're essential. But you can order it online as well or any store any bookstore, wherever, has my book. It's out there.

Kelly Therese Pollock 40:10

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 40:13

No, I think this is a really great conversation and I really appreciate the chance to talk to you.

Kelly Therese Pollock 40:18

Thank you so much. I loved the book and I really enjoyed speaking with you.

Dr. Blair LM Kelley 40:23

I love when people read it, it feels good. You work on it for so long by yourself. And you just don't know how it's gonna go over. So it's just wonderful to be in conversation with me. Thank you so much.

Kelly Therese Pollock 40:33

Thank you

Teddy 41:15

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode, and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on twitter or instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Blair LM Kelley

Blair LM Kelley, Ph.D. is an award-winning author, historian, and scholar of the African American experience. A dedicated public historian, Kelley works to amplify the histories of Black people, chronicling the everyday impact of their activism. Kelley is currently the Joel R. Williamson Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and the incoming director of the Center for the Study of the American South, the first Black woman to serve in that role in the center’s thirty-year history.

Kelley is the author of two books that trace the protests that toppled segregation and the people and movements that challenged the inequities of race and class. The first, Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship (UNC Press), chronicles the little-known Black men and women who protested the passage of laws segregating trains and streetcars at the turn of the twentieth century. Right to Ride highlights the women and men who led and participated in protests, recounting those thousands of Black southerners who fought valiantly for equal treatment despite the tremendous threat of racial violence. The first book-length treatment of the streetcar boycott movement, Right to Ride was awarded the 2010 Letitia Woods Brown Memorial Book Prize from the Association of Black Women Historians, and has become canonical for scholars studying the history of segregation, civil rights, and Black women’s history, reviving scholarly interest in the streetcar boycott movement and turn of the century African American activism.

… Read More