Phillis Wheatley

One of the best known poets of Revolutionary New England was an enslaved Black girl named Phillis Wheatley, who was only emancipated after she published a book of 39 of her poems in London. Wheatley, who met with Benjamin Franklin and corresponded with George Washington, was the first person of African descent to publish a book in English. Wheatley achieved literary success and helped drive the abolition movement, but she died young and penniless, and many of her poems were lost to history.

Joining me to discuss Phillis Wheatley is Dr. David Waldstreicher, Distinguished Professor of History at the City University of New York Graduate Center and author of The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley: A Poet's Journeys Through American Slavery and Independence.

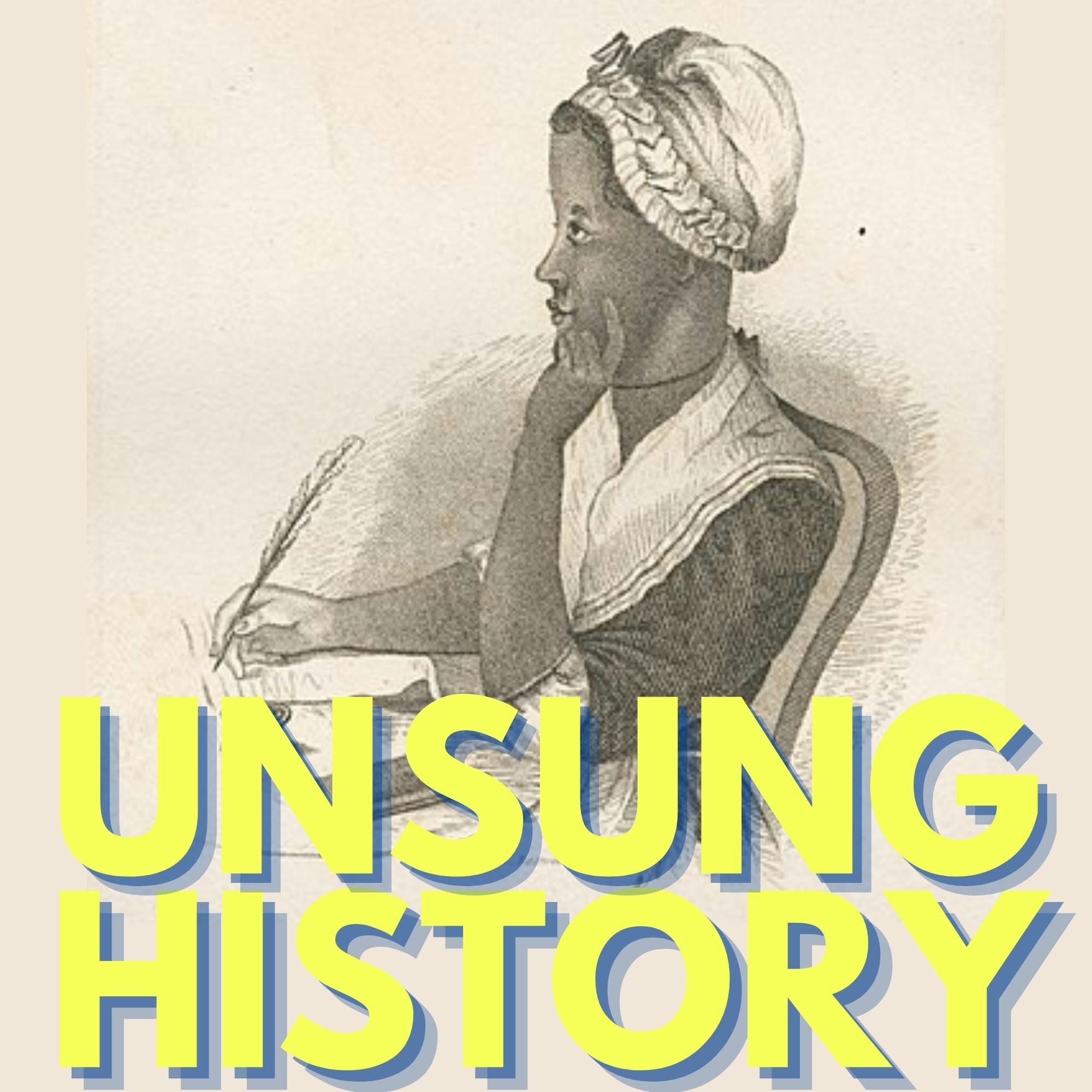

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode performance is poetry of Phillis Wheatley, read by Laurice Roberts for this podcast; the poems are in the public domain. The music is “Morning Dew” by Julius H. from Pixabay and is used in accordance with the Pixabay Content License. The episode image is a portrait of Phillis Wheatley, possibly painted by Scipio Moorhead, which was used as the frontispiece for her 1773 book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral; the portrait is available via the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and is in the public domain.

Additional Sources:

- “Phillis Wheatley: The unsung Black poet who shaped the US,” by Robin Catalano, BBC Rediscovering America, February 21, 2023.

- “How Phillis Wheatley Was Recovered Through History,” by Elizabeth Winkler, The New Yorker, July 30, 2020.

- “The Multiple Truths in the Works of the Enslaved Poet Phillis Wheatley,” by drea brown, Smithsonian Magazine, June 24, 2020.

- “The Great American Poet Who Was Named After a Slave Ship,” by Tiya Miles, The Atlantic, April 22, 2023.

- “Phillis Wheatley: 1753–1784,” Poetry Foundation.

- “Phillis Wheatley: Her Life, Poetry, and Legacy,” by Stephanie Sheridan, National Portrait Gallery Face to Face Blog.

- Phillis Wheatley Historical Society

- “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” by Phillis Wheatley, available via Project Gutenberg

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

Sometime around 1753, a little girl was born somewhere in West Africa, possibly in Senegal, or Gambia. She had a name, and a family, and a hometown. But we don't know them. The first time the little girl appears in surviving records, as far as we know, is when she arrived in Boston on a slave ship on July 11, 1761, when she was around seven or eight years old. The ship was named the Phillis, which became the name of the little girl as well. Phillis, who was a sickly little girl, would not have been most buyers' first choice in the slave market. But Susanna Wheatley, the wife of wealthy Boston merchant John Wheatley, saw something in the girl, and purchased her. Someone in the Wheatley home, likely Susanna or her daughter, Mary, taught Phillis to read and write, and even tutored her in Greek and Latin. When she was 12 years old, Phillis Wheatley wrote a letter to Samson Occom the Mohegan missionary who had stayed in the Wheatley home, and she began writing poetry. When she was 14, Phillis Wheatley wrote a poem about two other visitors to the Wheatley home, Nantucket merchants, Hussey and Coffin, who had recently survived a terrible storm at sea. In the poem, Phillis asked, "Did fear and danger so perplex your mind, as made you fearful of the whistling wind?"

This was the first of Wheatley's poems to be published, in the "Newport Mercury" on December 21, 1767, but she would later published poems written even earlier. On September 30, 1770, Anglican evangelist, George Whitefield, one of the most popular preachers of the day, and yet another guest of the Wheatleys, died on a trip to North America, collapsing in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Wheatley, who had been writing elegies for years by that point, wrote a 62 line piece she called, "An Elegiac Poem on the Death of That Celebrated, Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned Mr. George Whitefield." The Wheatley family published the poem as a broadside, first printed on October 11, in Boston, and sold for seven coppers, with many reprints, including in London. There were many elegies written for Whitefield, but Phillis Wheatley's was the most popular, and she suddenly gained international fame. Capitalizing on that fame, Phillis decided to publish a book of 28 of her poems. Publisher Ezekiel Russell advertised for Wheatley's book in his newspaper, "The Sensor," on February 29, 1772, trying to generate enough interest for a presale of 300 books, which would give him the capital to print the volume. Unfortunately, whether because of lack of interest, or economic problems in Boston, Russell never published Phillis' book, and he folded "The Sensor" entirely after May 2 of that year. In May of 1773, Phillis Wheatley once again set sail, this time to London, with John and Susanna's son, Nathaniel Wheatley, on the London Packet After a five week voyage, they arrived in London, where Phillis Wheatley carried with her an attestation, signed by 18 of the most important men in Boston, including town selectman, merchants, ministers, and even the governor and lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, who certified that they believed the poems to have been written by Phillis. In London, Wheatley met with Lord Dartmouth, Lord Lincoln, Dr. Daniel Solander of the British Museum, Benjamin Franklin, and abolitionist Granville Sharp. After six weeks in London, Phillis departed, returning on the London Packet, this time without Nathaniel, who stayed in London, and by November of that year, was engaged to the daughter of a wealthy British merchant. On September 1, 1773, Wheatley's book, "Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral," was published in London, subsidized by Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. It was only the third book of poetry published by a North American woman, and the first book in English by a person of African descent. At some point soon after that, the Wheatley family freed Phillis. The exact date of her emancipation is unknown. A few months later, in March of 1774, Susanna Wheatley died after a long illness. Although Susanna had enslaved Phillis, and had freed her only after she achieved fame, Phillis still felt a complicated kind of affection for Susanna, writing to her friend upon Susanna's death, "I was treated by her more like her child than her servant. No opportunity was left unimproved of giving me the best of advice, but in terms how tender, how engaging. This I hope ever to keep in remembrance." Underscoring the complexity in this relationship, and her larger feelings about slavery, Phillis Wheatley wrote in a letter to Samson Occom in 1774, which he printed, likely without her consent, "In every human breast, God has implanted principle, which we call love of freedom. It is impatient of oppression and pants for deliverance. And by the leave of our modern Egyptians, I will assert that the same principle lives in us. How well the cry for liberty and the reverse disposition for the exercise of oppressive power over others agree, I humbly think it does not require the penetration of a philosopher to determine." Susanna's death meant that Phillis was left without her biggest champion, and not everyone would treat her so well going forward. Four years later, John Wheatley died, as did Mary, who by then was married to Reverend John Lathrop, leaving Phillis without any of her protectors. On April 1, 1778, just weeks after John Wheatley's death, Phillis Wheatley announced that she was marrying John Peters, a free Black grocer in Boston, and one who appears to have been well read. They were married by John Lathrop on November 26, 1778. Sadly, Mary had died just a couple of months earlier. Phillis took John's last name, and they live together in Boston, and in Middleton, Massachusetts. The couple had at least one child together, although some sources say they had three children. It appears that none of the children survived childhood. Wheatley Peters attempted to publish another book, a 200 page work that she called, "A Volume of Poems and Letters on Various Subjects," but the economy of Boston again didn't support publication, and she didn't manage to print the book. Phillis Wheatley Peters died on December 5, 1784, in Boston, at the age of only 31. Notices of her death appeared in several papers in Boston and elsewhere. Her husband attempted to publish her second book several times after her death, but he was never able to make it happen. Of the over 100 poems Wheatley is estimated to have written, 55 known to have been written by her survive. Joining me to discuss Phillis Wheatley is Dr. David Waldstreicher, Distinguished Professor of History at the City University of New York Graduate Center, and the author of, "The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley: a Poet's Journeys Through American Slavery and Independence." Before that conversation, please enjoy Laurice Roberts, reading a poem by Phillis Wheatley.

Laurice Roberts 11:15

To SM, a Young African Painter, on Seeing His Works. To show the lab'ring bosoms deep intent, And thought in living characters to paint, When first thy pencil did those beauties give, And breathing figures learnt from thee to live, How did those prospects give my soul delight, A new creation rushing on my sight? Still wondr'ous youth! each noble path pursue; On deathless glories fix thine ardent view: Still may the painter's and the poet's fire, To aid thy pencil and thy verse conspire! And may the charms of each seraphic theme Conduct thy footsteps to immortal fame! High to the blissful wonders of the skies Elate thy soul, and raise thy wishful eyes. Thrice happy, when exalted to survey That splendid city, crown'd with endless day, Whose twice six gates on radiant hinges ring: Celestial Salem blooms in endless spring. Calm and serene thy moments glide along, And may the muse inspire each future song! Still with the sweets of contemplation bless'd, May peace with balmy wings your soul invest! But when these shades of time are chas'd away, And darkness ends in everlasting day, On what seraphic pinions shall we move, And view the landscapes in the realms above? There shall thy tongue in heav'nly murmurs flow, And there my muse with heav'nly transport glow; No more to tell of Damon's tender sighs, Or rising radiance of Aurora's eyes; For nobler themes demand a nobler strain, And purer language on th' ethereal plain. Cease, gentle Muse! the solemn gloom of night Now seals the fair creation from my sight.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:47

Hi David, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. David Waldstreicher 13:50

It's great to be here.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:51

I loved reading your book and learning about Phillis Wheatley. I wanted to start by asking how you came to write this book.

Dr. David Waldstreicher 13:59

I'd written a little bit about Wheatley, in my first two books. The first was a study of celebrations and political culture, Fourth of July and nationalism. And I talked a bit about Wheatley as having engaged in some of that sort of writing as one of the early free African Americans who helped establish a tradition of engaging with American nationalism for anti slavery purposes. So that was just a paragraph. Then when I wrote a book about Benjamin Franklin's slavery, I found that there was this really interesting interchange between Franklin and Wheatley when Wheatley was in London, that I thought really hadn't been unpacked or treated critically. People tended to use it to say, "Oh, look, Franklin was sympathetic to Black people, maybe even an abolitionist at that point." And I thought, "Oh, this is much more complicated than that. There's more going on here." He goes to visit her, but then he says, "Well, I went to visit her like you asked me to," like his cousin in Boston asked asked him to. "But her master was rude to me. And I haven't heard anything else about it since." So what's going on there? So I tried to put that in the context of all the other things Franklin was doing and what Wheatley was doing. So that was, that was another level that was a couple of paragraphs. And at a certain point, I realized that maybe as a historian of the revolution and slavery, who has a PhD in American Studies and is interested in literary criticism, maybe I had something to add to our understanding of Wheatley, and what she was up against and what she was doing. So I wrote a few few articles, a few essays and, and gradually figured out how to make it into the kind of book I wanted to write.

Kelly Therese Pollock 16:00

So there's a lot in this book. There's a ton of sources that you're referencing, and looking at. I wonder if you could talk through a little bit what, what sources we have, what sources we don't have about her life? What we sort of can and can't know about her?

Dr. David Waldstreicher 16:15

Yes, well, the reason why there haven't been many biographies, really only one before mine and scholarly know plenty of juvenile biographies and more imagine novels for young adults, mostly really, based on what research is, was easily obtained, is that there isn't much, really in conventional terms for a biography. There are her poems, more of them than we had decades ago, but about 57 or 58, depending on, on how many one accepts as definitely having been written by her. I argue that there are some more anonymous ones that that she may have written that I include in the appendix. And there are about a dozen letters. But other than that, it's what I call footprints. She left things people said about her, how they responded to her, who they were. And that's been very limiting and unsatisfying in biographical terms, for the most part, and what I realized at a certain point was that this had also affected how even the literary criticism, much of which is really good and imaginative, and careful and scholarly, in that, because there were so many gaps in understanding her life, both in the beginnings, and even in the periods where we know that she was writing and publishing a lot, as well as the beginning, and the end, where we actually know a lot less of the last six years of her life, and the first eight years of her life before she comes to Boston. We know, we know very, very little, that people hadn't, who had studied her hadn't paid attention to her poems as being written at particular moments, for particular audiences. It was more like, "Let's read her poems and try to figure out what she thought about slavery or, or how religious she was, or what her identity was. She didn't have a long career, so it made sense to kind of treat things she wrote early like things she wrote later, unless one was looking for the evolution of her evolution as an artist, her skill, where where there was a clear evolution, or her increasing willingness, perhaps to take chances, and write in more ambitious genres or more ambitious poems. But mostly, it was kind of read her book, where she collects a lot of a lot of, but not everything that she had done up to 1773. And in a few of the poems that we have that she wrote later, and say, what Phillis, what kind of an artist Phillis Wheatley was. I, as a historian, I and as a political historian, especially I thought, well, you know, if she's if she's really as deeply engaged with what's going on in Boston, and the coming of the revolution that as some have realized, then 1765 is not the same as 1768, which is not the same as 1773, which is not the same as 1776. And writing to George Washington is not the same as writing to friends of her mistress or a minister in Boston. But the book really came together when I started to read the Boston newspapers, and when I say read them, I mean, look at every page and of all four or five Boston newspapers from the time she gets there, all the way through the rest of her life. This took a long time. But it's the kind of research I really enjoy. And then, so much started to fall into place about her cohort of Africans who arrived in New England after the seven year, during an after the Seven Years War, of what they were doing on the streets of Boston, about what skills they had, about about fact that she's not the only one who's literate and And what the various people who she interacts with, writes poems about, write poems for, who comment on her, what they're doing and what they're thinking. And this I feel enabled me to contextualize and fill in a lot of the gaps with with reasonably plausible interpretations and speculations about what she was doing. I guess the most important thing is that I structured the book then as a story about how she gets from one poem to the next one important. Next one, one sort of set of issues that she works through with her poetry. So the chapters are short, and they're often built around one or two poems, which I talked about as as actions and as the best evidence for what was going on with her at different times.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:46

So let's talk too then about the literary environment in which she's writing, because I think it's hard for us to put ourselves back into what literary references everyone would have known then, and what she was reacting to. So could you talk a little bit about that, and she's clearly responding to the literary world in which she lives?

Dr. David Waldstreicher 21:05

I believe the most important thing to realize is that poems are popular culture at this time, that probably the best comparison would be, would really be music, songs, today, in the sense of just how many people share in it, have their favorites, have their genres, but nonetheless, it is a place where you see people working out issues that are sometimes personal and spiritual, sometimes political, sometimes a mix of the two. And while that is true, it's also true that poetry is more open to women. Usually, they don't, usually they publish anonymously. But it is a set of forms that they expect that many women are familiar with, and expected to appreciate. And also that Boston is pretty much the most literate town in English, as literate as any place in the English speaking world. So it's, while the other really important thing to realize is that Phillis Wheatley is part of an evangelical project. Her owner, Susanna Wheatley was very much involved with Methodist and evangelical Protestant outreach outreach to Native Americans, and to other enslaved people. The patron in England, who they eventually reach out to to help publish the book also sponsored some of the first published slave narratives. So there is this sort of, there's a religious subculture that is very involved, that is very interested in the uses of literacy, and also uses poems and and hymns in their everyday practice. And then there is the neoclassical revival, the publication of translations of Greek and Roman classics, in English meter, by poets like Alexander Pope, which become bestsellers. So she's responding to all of that. And I think we most it's sometimes the religious part of it is more obvious, because though that some of them some of the first poems, she writes, and some of the most famous ones, are so obviously pious, and put her in the position really, of a kind of lay minister, telling people what to do to be saved, how to respond to the death of their children, or their or their friends or their loved ones, or their relatives. But there's also this way in which this Greek and Roman world, especially Homer and translations of Homer, but also others, like Horace, and Virgil, are those poems, the epics, but also the epistles and the satires, and all the different kinds of neoclassical poetry, depict a world that has women, that has enslaved people, that has shipwrecks and dangerous voyages and enslavement. So in engaging with this literature, she is able to, I think, talk about and play with realities in this ancient Mediterranean world that are not that much different than what she experienced in Africa and in the Atlantic, and which enabled her to talk about things that nobody heard that white people didn't want to hear her talk about directly. So that's why the book is called, "The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley."

Kelly Therese Pollock 24:42

Let's talk a little bit about this weird position that she has within the Wheatley family, the white Wheatley family, and you know she she comes into the family is bought as a seven or eight year old which is unusual in itself. And then she has this weird position where she's kind of companion and still enslaved kind of kid they want to promote her. What what's going on here? What What were you able to unpack about this weird relationship?

Dr. David Waldstreicher 25:10

Right that's that's a very that's it's a very important question. The fact that she is not only taught how to read, but then put forward as a genius, a prodigy, and the Wheatleys play a central role in getting her poems published, has usually been interpreted to mean that she's kind of an experiment, and she's not really even, if she's enslaved, she's not a typical slave. So she doesn't tell us anything about the experience of slaves, or about slavery or even about maybe the struggle against slavery, that is broadening and becoming a real thing, in this time and place. I think that's, I think that misunderstands the way, the what all the different things that enslaved people did in New England, in the 18th century. The fact that they were an important part of the labor force, and the fact that they were all embedded in families, just like orphans and indentured servants, and apprentices, everyone had to be in a fair in a family. That doesn't mean it wasn't slavery, though. It does mean they were often treated as inferior members of a family and talked about that way. The difference was, that they could be, and often were, sold, when, as well as mistreated in the way that slaves always had been throughout history in many ways. But the key thing here is if they lived under threat of sale. That could either be for misbehavior, or for financial opportunity, or most commonly when their owner died, and the estate was broken up, or they or was transferred to someone who held a debt or family members. That made it very hard for them to have families of their own. So and if that isn't slavery, I don't know what is. And it doesn't we don't have to compare it to laboring in the sugarcane on a plantation in the West Indies in order for it to be real slavery, or for it to be racial slavery, which so clearly was, and at a time, when more and more people were starting to use racial differences as an excuse to justify something that they knew very well didn't accord with their other values. So how does all this play out in the Wheatley family? Well, we might think of the Wheatleys as kind of reformers. They want to make slavery better, they want to make it not as bad as it is in other places. And they want people to convert their slaves and raise them up as good Christians, which will then be a project that may even convert the heathen in Africa, and everybody will live happily ever after. So that's their larger project. The thing that's going on in the household also is that they are that is that they have their only surviving children at this point are twins Nathaniel and Mary, who when Phillis arrives at age seven or eight are about age 18. And they had a younger child who died and they had other young children who died young. And Phillis becomes basically the the the younger child that didn't that didn't survive at a time when the others are growing up, but it becomes a kind of family project. But she also, I think, Susanna Wheatley becomes emotionally dependent on her. And I think that's clear from the testimony we have about how Susanna felt we don't have much from Susanna. We have "as told to" stuff how Susanna felt about her and what Phillis herself says about their relationship. And Phillis, frankly, uses that to improve her position and do some things that she wants to do. And I think I think it's not a leap to say that she had a very ambivalent relationship, could only have had a very ambivalent relationship, to Susanna, and to the rest of the family, in which it was clear that they cared about her but also increasingly clear that what her adult life was going to be like, as the Wheatleys are getting old and ill, and Nathaniel and Mary are growing up and getting married and trying to have lives of their own and maybe a little bit jealous too. I think there's some evidence that they were. There's some tension in the family over over her role and how much attention she was getting. That these are the things that she was dealing with, and that as a result, she doesn't know how things are going to turn out and she's trying to leverage her increasing fame and skill to try to to become free and have what what the other young adults want and have a that time.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:00

I want to pick up on the way you were just describing her as an actor in this situation. I think it's easy to sort of think of her as as passive, but she's very clearly an actor, here. She is working not just toward her own freedom, but is trying to argue for slavery's end. Can you talk a little bit about that? Because she seems so politically savvy in a way that must have been extraordinarily difficult to navigate for her.

Dr. David Waldstreicher 30:30

Yeah, she gets herself into a position where, at the very moment when the Anglo American conversation about slavery is intensifying, and we're seeing we're seeing a kind of explosion of anti slavery literature and conversation inflected by the imperial controversy. People are starting to say, on the one hand, "Well, if we're if we're going to fight for, if we're going to talk about liberty and how the British are enslaving us, maybe we need to think differently about slavery." I think even more important is the fact that people were skeptical about the about those claims, started to throw the facts, the overwhelming fact of North American slavery in the faces of the patriots. And Wheatley very candidly keeps her options open and lines of communication open both to people who are sympathetic and critical of the Americans, as long as she can, and knows very well who her audiences are, and uses the opportunity she has to suggest that maybe there's that, yes, the patriots have a point in insisting on their liberties, but maybe there is something inherently wrong with enslaving others. And also, I think, just while doing so, like, accepting that she's being perceived as an African and as a an example of African potential, and as a kind of one woman anti slavery argument argument against the inferiority, or the inability of Africans to assimilate or to become equal members of Anglo American society, on the one hand. Because of her skill, she's showing that, "Oh, well, you know, maybe like, slaves who deserve it, or slaves who become adults or slaves who were productive, then deserve to be freed at some point." So that there's that kind of reformist argument. I think that's, that's what she's assuming in the beginning, because she's reading these Greek and Roman classics, it's very clear, that very skilled slaves get emancipated, one way or the other. That's the Roman slavery. It happens all the time as it were. So that there's that aspect of it. But then there's also this other dimension to it, where she uses the hypocrisy arguments and insists that yes, I'm African, but look at what I'm doing. Look at how I'm supporting the patriot movement. I am British, I understand British liberty, British culture. And I am eventually I am also American. So I think this is like, I particularly want to underline this, that it becomes very clear that she that against other people pushing her in different directions, she insists that she's African and British and American, and there is no conflict or contradiction between those identities. And in fact, her politics depends on her insistence of being all three.

Kelly Therese Pollock 33:28

You mentioned earlier that there's this cohort of both free and enslaved Black people in Boston, in New England at the time. Could you talk a little bit about her relationship with that cohort? That seems really important to her ability to sort of realize there's this larger audience to talk to.

Dr. David Waldstreicher 33:46

We don't we don't have a lot of evidence about her relationships with other Africans in Boston. What we do have is a lot of evidence that it was a community, that that enslaved people had friends and relationships beyond the families that they lived in, and that this was something that that happened and was very common and was sometimes a matter of great concern to the authorities. We have more evidence of her friendship with Obour Tanner, who lived in Rhode Island and who it's been speculated may have been a shipmate, may have come over on the same ship. They seem to know each other. There's a closeness that so either either the Wheatleys went to Rhode Island or Obour Tanner's owners brought her to Boston on numerous occasions because they're corresponding in a way that suggests a closeness of proximity. And then Tanner also introduces her and then later on she in 1775, she actually is in Providence for a while so she interacts with these folks, and but it's clear she gets to know some of Tanner's friends, some of the leading free and enslaved members of the First Church in Newport. And that there's enough evidence, and I want to single out, Tara Bynum who's written about this so fascinatingly and eloquently. There's plenty of evidence that she is even if she is not writing directly for that community, she is informed by them, and by their strivings, and that those friendships are, are important. But I think it's just as important that we can see other Africans and descendants of Africans writing poems, saying and writing and publishing against slavery, that that's going on in 1773, 74, 75. And that is informing her strategies. She knows that she is becoming the most famous among them, and kind of a spokesman, a spokesperson, but she's also being very, very careful not to lose those opportunities by offending her her various constituencies. It's a very delicate, very careful dance that she that she is doing, and one that becomes more and more difficult as protest turns to war.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:18

Another thing that happens then, on the eve of revolution, not the immediate eve, but she goes to London. You mentioned earlier, she met with Benjamin Franklin. She's still enslaved at this point. She goes to London to pull together this book that she wants to publish. Could you talk about this trip a little bit, and it's clearly so monumental, both in the ability to publish the book, but then in her life after that.

Dr. David Waldstreicher 36:41

One key thing about the visit is that it's partly a response to the difficulty of getting her poems published in Boston. The more the more anti slavery printers, who who had proposed to publish her book aren't doing that well, economically, or they don't get enough subscribers, it's getting, the economy's not so great, it's getting harder to publish a book in Boston. And, frankly, some of the, I think some of the patriot printers are a little worried about the implications and whether it might be thrown in their faces and turn out to be embarrassing. And they get opportunities to, as I said, to publish in London, and maybe that will be an even bigger publishing event. And she helps make that happen, by writing a letter to Countess Huntingdon when she writes her elegy on the death of George Whitfield, by writing a poem to Lord Dartmouth, and getting it into the hands of someone of someone who actually knows Dartmouth and brags about knowing Dartmouth, and her, her owners, the Wheatleys, they own a ship, that that goes several times a year. And Nathaniel is planning on going. So they set it all up that she's going to go over and oversee the publication of the book, as it were. But they don't say that. In Boston, they say, "Oh, she's she's, well, she is going she is being patronized by Countess Huntingdon." That gets mentioned, but they kind of hush that up and they say she's going for her health, but it actually makes it into the newspapers. It's just a great example of the very careful like, "No, I'm not I'm not overdoing this. I'm not putting myself forward," even though like like and it is true that she had she had an chronic probably asthmatic condition. But people didn't go to London for them. They took to sea air for their health, but they didn't go to London, they didn't go on like a six week voyage on the ocean, in the North Atlantic, Atlantic for their for their health, really, and certainly not to stay in London, notoriously, smokey, smoggy, damp London for their health. People left London for their health. So she gets there and she's shown around, feted, she's, you know, immediately goes to see major patron of the arts in an episode that doesn't get much attention. It hasn't hasn't been noticed by scholars, because the the guy, the guy is all elderly and dies with these this guy, this Lord who had sponsored poets for decades. And she gets shown around town by the anti slavery activist Granville Sharp, and he takes her to the Tower of London. And she writes letters back saying about how about all these amazing people she met and Lord Dartmouth gives her books and Benjamin Franklin and everything, and she signs copies of the book, so that people will you know, so that they're not they don't get pirated. She signs the frontispiece of at least 100 copies. Half of the excellent ones are actually signed by her first edition. And just as importantly, though, by the time she's getting ready to, she comes back, it's very clear that she has been, the people are asking, "You mean she's still a slave? Really?" And one of the reviewers who said who doesn't even say your poems are that great but but can't resist the opportunity to say, "Doesn't it just show how hypocritical the Americans are, that they would keep this obviously highly skilled person in chains?" So the Wheatleys are kind of, have to free her. It's embarrassing. This thing that made them look really good is all of a sudden making them look like a scandal. It's one of the last things I decided to do in the book, because I can't say for certain how it happened that she became free. And so I wanted to be very careful about it. But in a chapter called, " The Emancipation," I lay out four scenarios, based on the evidence we have of how this happened, that she became free soon after, or while she was in England based on the evidence we have. And the evidence is murky, not just because it doesn't exist. The evidence is murky, because she said different things about it to different people. So so why did she say different things about different people? Well, it's because she was an actor in her own emancipation, but she couldn't claim to be that. So she's saying, "Oh, they decided to free me," or "My friends in England, at the behest of my friends in England, I've been freed," she says to what she says to one person in London and then to people and, and then to others, she says, "My, my master and mistress have decided to free me." And then but then there's other there's other evidence that where like it may have been whispered that she was going to be freed anyway, so. So in one way or another, that over this process of her going to London, it wasn't an emancipating moment, but very revealingly, that is not that's not the public transcript. That's not the thing that can be said, and celebrated the way we would tell the story of this triumph, that like that the publication of I mean, it may be because no one could imagine a published author owns the property of their book. Can someone who is owned, own their book? It creates a legal conundrum. I mean, it may have been, it may have been the realization. It may have been in the works already, but then going and embarrassing, sped it up. So I lay out these different these different scenarios. But the important thing is that we can see that not only is she an actor and making it happen, she's an actor in control, or in clouding the meaning of it, to keep her options open so that she doesn't offend people who don't, who might have issues with her exercising that much power over her fate.

Kelly Therese Pollock 42:10

So you mentioned we don't know a lot about the end of her life. What what do we know about the end of her life? And what are the reasons we don't know a little bit more?

Dr. David Waldstreicher 42:21

The reason we, the reason we don't know much is partly a result of her emancipation. When she's emancipated, she still is writing ambitiously. But she, outside of the Wheatleys' orbit, and because of the fact that quarter to a third of the population leave Boston, there's an out migration, a lot of a lot of people who are supporters, and a lot of the Wheatleys' friends are getting old and dying off. And so she really has this loss of patronage and she really has to kind of find her own way trying to sell her books. And she's on she's, she leaves Boston with with Mary Wheatley and her husband, goes to Providence, comes back. And it's very hard to tell exactly what she's doing. But it is clear she's still writing, writing quite ambitiously, writing poems about Revolutionary War generals, for example, and trying and working on a second book manuscript, but we one of the reasons we don't know much is that all the Wheatleys die off. Nathaniel dies, even like around in the early 1780s. Also, Mary dies in 1778. And so there's no Wheatley estate. We know even less about the white Wheatleys than we do about Phillis actually, because there's practically no like most of the letters that have survived, they're connected to Phillis. There should be more than just other people's other Bostonians papers that have survived. It's, there's just so little that we that we actually have about them. So there's no so there's very little to go on in terms of of where she lived and what she and what she was doing. Another factor is that she when it becomes clear that John Wheatley dies, and does not leave her any property, and the house is going to be sold, that she may have helped take care of him in his in his declining years, as the rest of the family is out of the picture, she she very quickly gets married to this very impressive man named John Peters, who was a did a bunch of different occupations and but was well known for representing himself and others in court. And I think there's enough testimony to make it clear that he was quite impressive and literate, and that she really made a made a completely logical choice that you would expect. She married she married one of the more impressive Black men in Boston, exactly what you would expect her to do. And they actually have have some property that we can see in tax records and Cornelia Hughes Dayton has done some wonderful research on this, recently published an article in the New England Quarterly about two years ago. But like so many In Boston during the Revolutionary War, they they get into debt, they move to an to a rural town where John Peters was from and where he has some prospects of being able to take care of the house and lands he grew up in, in, in a kind of trade. I think I think of it actually as a kind of reverse mortgage, where he's going to take care of the widow and their disabled, younger daughter and the farm, and, and he's eventually going to inherit it. And there may have even been a family connection between that family. But it's speculation. But I think that's a logical presumption. In a couple of years, though, it all falls up, it all falls apart. And they get they get kicked out, and with not much to show for it. They come back to Boston, there's some testimony that Phillis, that they have children. Phillis is working. But John Peters ends up in in debtors' prison, which is actually not that uncommon, or that or even that big a deal. It just means that they're trying to try to get somebody to pay his debts. And you know, it was a way to coerce people into getting their friends to pay their debts for them. And, but she's she's sick, and she passes away in early 1784, while he's in debtors' prison. So there's very little on their experience that last six years, but it's very clear, she kept writing, she kept publishing at a time when it was a lot harder to publish her poems in in fewer newspapers, and magazines, but she's still doing it, she still publishes some broadsides. And it's clear that she has a book manuscript that she's waiting to publish, and that people are talking about. So often, this has been told as a tragic story of great talent and the loss of her, which is a tragedy, the loss of a lot of her poems that, that that didn't serve that never did get published. But it's also not an uncommon one at a time when there are no careers for poets, really, you know, while the other the notable poets of Boston were ministers, and independently wealthy people, lawyers, like James Bowden, they had other jobs, they didn't make a living on their, on their poetry. She's different in some ways. You could say she's one of the first people to try to do that. And it's not surprising that it didn't work out. And so like many, like, I mean, it's almost a stereotype that the poet of the Romantic era, who dies alone in a garret. It's a common trope in Anglo American literature in the late 18th, early 19th century. And that was her experience. So we can emphasize the tragedy in it but we can also I think it's it's more important to realize just how much he did accomplish in a short time, and how the American Revolution both actually floated her project, but at the, but in the end, also made it very, very hard to continue.

Kelly Therese Pollock 47:43

Yeah. Well, there is so much more in the book that people can read. Can you tell people how they can get a copy?

Dr. David Waldstreicher 47:50

Well, hopefully at any bookstore or online, in all the usual places. It's published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. It's been out since March. There are there the usual is an audio book, there's a Kindle version, and there'll be a paperback next March.

Kelly Therese Pollock 48:05

The audio book is terrific. I listened to it. I really, really recommend it.

Dr. David Waldstreicher 48:09

It's not me. It's done by a fabulous actress named Kim Staunton, haven't met her, but she did a fantastic job.

Kelly Therese Pollock 48:15

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. David Waldstreicher 48:18

No, it's been a lot of fun. Thank you for the opportunity to try to get it all into a half hour.

Kelly Therese Pollock 48:25

Thank you. I really appreciate you talking with me and I love the book.

Dr. David Waldstreicher 48:30

Thank you.

Teddy 49:02

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode, and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain, or are used with permission. You can find us on twitter or instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

David Waldstreicher

David Waldstreicher is a historian of early and nineteenth-century America with particular interests in political history, cultural history, slavery and antislavery, and print culture.

He is author of Slavery's Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification (2009); Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery and the American Revolution (2004); and In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776-1820 (1997). As editor, his books include Revolutions and Reconstructions: Black Politics in the Long Nineteenth Century (2020); the Library of America edition of The Diaries of John Quincy Adams (2017); Beyond the Founders; New Approaches to the Political History of the Early American Republic (2004); and The Struggle Against Slavery: A History in Documents (2001). His scholarly articles and books have won prizes from the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, the, Southeastern American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies, and the American Jewish Historical Society. He has also written for the Boston Review, Atlantic.com and the New York Times Book Review.

Waldstreicher is an elected member of the American Antiquarian Society and the recipient of awards and fellowships from the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers, New York Public Library; the American Philosophical Society; and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, among others.

Before coming to the Graduate Center, he taught at Temple University, University … Read More