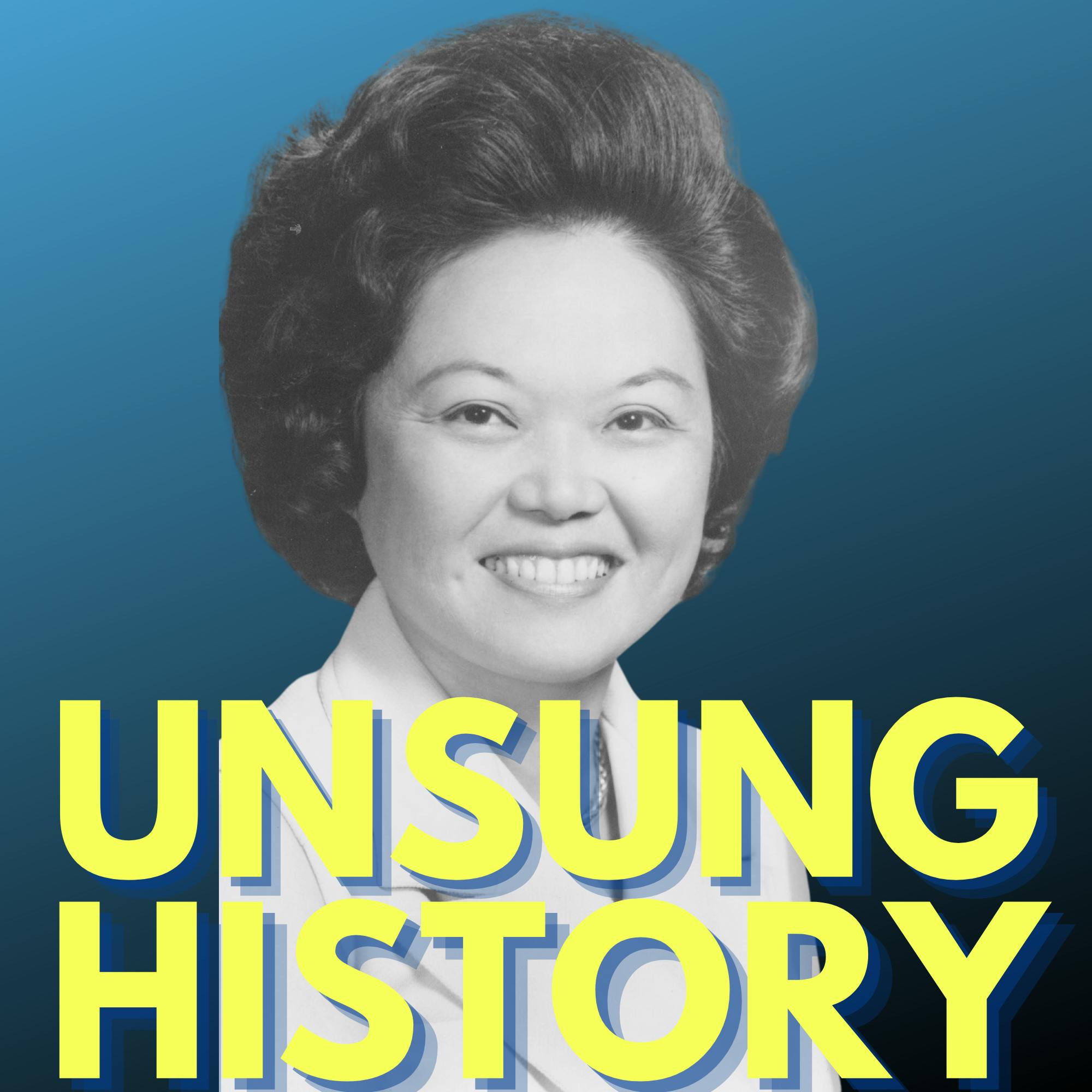

Patsy Mink

In Patsy Mink’s first term in Congress in 1965, she was one of only 11 women serving in the US House of Representatives, and she was the first woman of color to ever serve in Congress. Mink was no stranger to firsts, being the first Japanese-American woman licensed to practice law in Hawaii, after being one of only two women in her graduating class at the University of Chicago Law School. She would later be the first Asian American to run for President.

Mink leaned on her own experiences of sexism and racism in writing and supporting legislation to help women, especially women of color and women in poverty. MInk co-authored and supported the landmark Title IX Amendment of the Higher Education Act, that stated that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” After Mink’s death in 2002, Title IX was renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act.

Joining me to help us learn about Patsy Mink are Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, Professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Irvine, and Patsy Mink’s daughter, Dr. Gwendolyn (Wendy) Mink, former Professor of Politics at the University of California, Santa Cruz and former Professor of Women and Gender Studies at Smith College. Drs. Wu and Mink have co-authored a new book, Fierce and Fearless: Patsy Takemoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress.

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. Image Credit: “1972 campaign poster image from the Patsy Mink for President Committee,” Congressional Portrait File, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-122137) - Patsy T. Mink Papers at the Library of Congress. Image is in the Public Domain. Audio Credit: “The National Commission on the Observance of International Women’s Year 1975 sponsored this conversation with Rep. Martha Griffith (D-Michigan), Rep. Patsy Mink (D-Hawaii) and Wendy Ross of the U.S. Information Service.” November 26, 1974. Video/Audio is in the Public Domain.

Additional Sources:

- “MINK, Patsy Takemoto,” United States House of Representatives Archives.

- “Patsy T. Mink Papers” at the Library of Congress

- “Women who made legal history: Patsy Mink,” University of Chicago Law School, March 31, 2021.

- “Rewriting the Rules: Celebrating 50 Years of Title IX,” The William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

On this week's episode, we're discussing the first woman of color to serve in the US Congress, Representative Patsy Mink. Patsy Matsu Takemoto was born in Hawaii territory on December 6, 1927. She was a third generation Japanese American or Sansei, born to Suematsu Takemoto and Mitama Tateyama Takemoto. In 1944, Patsy graduated from Maui High School, where she was class president and valedictorian. And she chose to attend college on the mainland, first at Wilson College in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and then at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln. At the University of Nebraska Patsy organized a coalition of students, parents, administrators and others, to lobby to end the racial segregation policy that required students of color to live in separate dorms from white students. The coalition was successful, but because of illness, Patsy returned to Honolulu for her final year of college, graduating from the University of Hawaii, where she earned Bachelor's degrees in zoology and chemistry. Patsy had planned to become a doctor, but she was denied admission by several medical schools because she was a woman. So instead, she went to law school, graduating from the University of Chicago Law School in 1951. Patsy was one of only two women and one of only two Asian Americans to graduate in her class. At the University of Chicago, Patsy met a graduate student in geology, named John Francis Mink. They married in 1951, and in 1952, their only child, Gwendolyn, was born. The family moved to Hawaii, where John worked with the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association. Hawaiian territorial law said that Patsy had lost her Hawaiian residency when she got married, and they wouldn't permit her to take the bar examination. Patsy challenged the sexist law, and the Hawaiian Attorney General ruled that she should be permitted to take the exam. When she passed in June, 1953, Patsy became the first Japanese American woman licensed to practice law in Hawaii. However, law firms would not hire a married woman with a child, so Patsy opened her own private practice, and then became active in politics. Here's Patsy Mink, talking in 1975, about how difficult it was to break into legal work as a woman. "It was really very difficult. I hate to say it, but and I won't mention the name of the law school, but I got into my law school on the grounds that they considered me a foreigner. I got in on the foreign quota. Someone in the law school had not read up their American history, and hadn't realized that Hawaii was annexed in 1898, and that we were all American citizens. But it was very difficult getting into into school and getting into the professions. I couldn't find a job. And when I'd hear my contemporaries at home say, 'Oh my goodness, what you've done to politics at home and you know, we wish we had never heard of Patsy Mink,' I'd say, 'Well, it's because of all of your attitudes that drive men to politics. If you'd have given me a job when I came home from law school, I would have been very happy, just drawing a paycheck each month.'"

Patsy's work with the Young Democrats led to her running for office herself, and she was first elected to the territorial House of Representatives in 1956. She moved up to the territorial Senate in 1958. When Hawaii became a state in 1959, Patsy ran for the US House, but the Democratic boss of Hawaii, John Anthony Burns worked against her, and she lost her primary. After a term in the Hawaii State Senate from 1962 to 1964, Patsy again ran for the US House, when reapportionment created a second at-large seat for Hawaii. This time she won, making her the first woman of color to serve in the US Congress. In the US House, Patsy served on the Committee on Education and Labor, which allowed her to focus on her key issues. She introduced or sponsored legislation on child care, bilingual education, student loans, special education, and Headstart. In 1971, her legislation to institute a national daycare system was passed by both houses of Congress as part of the Economic Opportunity Act. But President Richard M. Nixon vetoed the bill, in what Patsy called one of the real disappointments of her political career. In 1974, Congress passed a comprehensive education bill, which included Mink's Women's Educational Equity Act. Here's Patsy, talking about the act. "It's always been my belief that no matter how many laws we passed, or how many constitutional amendments we were successful in having ratified, that the major problem in any society was the attitudes that people grew up with, or were made to believe were sacred traditions of their civilization. And so long as any part of our society adheres to a sexist notion that men should do certain things, and women should do certain things, and then begin to inculcate our babies with these notions, through curriculum development and so forth, then we'll never be rid of the basic causes of sex discrimination. So the Women's Educational Equity provision, which is designed to provide monies for small groups, institutions, women's organizations, school systems, universities, whatever, to try to grapple with this problem, do some very intensive work in curriculum revision textbooks. Why do all the women for instance, in a child's primer have to be pictured as homemakers with aprons on in the kitchen, and never anything very exciting beyond being a nurse? The doctor is always a man, the lawyer, the engineer, the statesman is always a man. And this is the kind of very subtle way in which, in my view, girls and women are discouraged from fulfilling their potential. And so I suppose the purpose of my bill is really to free the human spirit to make it possible for everyone to achieve according to their talents and wishes."

Patsy workedwith Representative Edith Starrett Green of Oregon, and Senator Birch Evans Bayh of Indiana, to build support for Title Nine of the Education Amendments of 1972, landmark legislation that prohibited sex discrimination in any education programs. Patsy Mink became the first Asian American woman to run for president in 1972, the same year that Shirley Chisholm ran. The two were not competing against each other. Mink was on the ballot in only a few states, and she was running to draw attention to the anti-war movement. Her opposition to the Vietnam War led some opponents to call her Patsy Pink. In 1976, she ran for the US Senate, but lost the primary to fellow House member Spark Matsunaga. Once out of Congress, Patsy served as the Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs in the Carter administration, and then for three years was president of Americans for Democratic Action. Finally, she returned to Hawaii and was elected to Honolulu City Council, where she served from 1983 to 1987, chairing for part of that time.

After unsuccessful runs for mayor and governor, Patsy ran again for Congress, with the campaign slogan, "The Experience of a Lifetime." On September 22, 1990, Patsy Mink returned to the US House, where she once again served on the Committee on Education and Labor, and she was also appointed to the Government Operations Committee. In her second service in the house, Patsy co-founded the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus in 1994, and served as its chairwoman for several years. Often in the House minority, Patsy found herself opposing legislation that challenged the progress made in her earlier time in Congress. Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Patsy worried about the ramifications of the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security. As a Japanese American, Patsy knew well how civil liberties can be undermined in the name of national security. In 2002, Patsy contracted chickenpox, which lead to pneumonia. After a month in the hospital, Patsy died on September 28 of that year. She was 74 years old. She had won the house primary just a week before she died, and her name remained on the ballot in November, 2002, when she was posthumously re-elected to Congress. Her vacant seat was filled by Ed Case after a special election. After Patsy's death, she was awarded a Medal of Freedom, and Title Nine was renamed the Patsy Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act. Joining me now to help us understand more about Patsy Mink and her incredible life are Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, Professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California Irvine, and Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink, former Professor of Politics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and former Professor of Women and Gender Studies at Smith College, and the chair of the Patsy Takamoto Mink Education Foundation for Low Income Women and Children. Doctors Wu and Mink have co-authored a new book, "Fierce and Fearless: Patsy Takamoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress." Judy, Wendy, thank you so much for joining me today.

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 13:30

It's a pleasure to be here.

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 13:32

Thank you for having us.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:33

I am so excited about this episode. So I wanted to start maybe just by talking a little bit about how this project came together. So I know Judy, you had been working on this for a while before Wendy got involved. So can you talk sort of how you got the idea for this book and started working on this project?

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 13:53

I started in 2012. And I remember when I first met Wendy, and she asked how long I thought the book would take. I said maybe 10 years because that's been the average for my other books. I think she was really shocked, but 10 years later, here we are. And actually I think Wendy has a longer history with this project given that she was Patsy's daughter, she is Patsy's daughter, and that Patsy wanted me to to work on the project. I found Patsy's papers at the Library of Congress website. And as a historian I'm so excited when there's archival collections. But I was surprised at the level of materials that were that were in the archives. There's 2700 boxes. I had always known of Patsy Mink, and actually I was a little bit surprised that no one else had written a book about her. I remember emailing my friends and colleagues just saying, "Is anybody working on her?" So it just felt like such a wonderful opportunity to be able to try to document her life and to share that with the public.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:55

So Wendy, had you considered before Judy got in touch with you, doing anything, writing a book or anything about your mom?

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 15:02

Yes, I had. I was sort of in the process of sort of agonizing with myself about how to exactly go about writing the book. My mother's papers are all at the Library of Congress. It took a few years for the papers to be processed by the archivist, and so forth. But when that process was completed, I started to sort of putter around episodically in the collection to basically on a chronological basis sort of track out the elements of the story that I would need to compile. And that puttering began in maybe 2007, 2008. By 2010, 2011, I was kind of at a point where I would write about the early part of her life up to her opposition to the war in Vietnam. But at that moment, I was besieged by sort of intra- psychic, angst over the choice of voice that I needed to make, to tell the story, because I am a scholar, I'm a political scientist. And everything that I've ever written has been in that voice of a third party, outsider, and dispassionate observer and analyst and so forth. But on the other hand, this would be an intimate story of my mother's life. So I kind of whined and agonized and sort of treaded water over those issues, until miraculously Judy entered my life.

Kelly Therese Pollock 16:39

And it's it's such a wonderful collaboration and solution that that you have done that we get to have these these more sort of intimate vignettes from Wendy, and then the more analytical, dispassionate pieces from Judy. So I really loved that you were sort of able to put that together. What did that process of working together and sort of figuring out the structure of the book, what did that process look like?

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 17:09

I began just by informally consulting with Wendy. And then we did oral histories. And then I learned about her mother's desire for her to write her biography. And I think it just made a lot of sense for us to collaborate. But I also liked the idea of having two distinct voices, because Wendy has these powerful memories that are so beautifully written in the book, and I wanted to make sure that her voice was there. We played around a little bit with the formatting, because should the historical chapters come first? Or should her vignettes come first? And I really liked what we've settled on. And actually, the process of trying to figure it out, figuring out how we're going to put our two pieces together shaped the way we wrote our thesis. So early on, I would write the chapters and then Wendy would write the vignettes and then Wendy wrote the vignettes, and I wrote the chapters. So we were actually both, we're not looking at each other's writings, we talked about the topic that would be in the chapter, but we didn't look at each other's writings, as we were composing our own. And only afterwards, did we come together and think about the ways in which they they interval with each other.

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 18:15

We were concerned about possible redundancy, right, between the memories and the historical narratives. So, you know, certainly when we brought the pieces together to sort of create the tableau that is the book, we had to be aware and pay attention to correcting any issues that arose, but it all kind of, you know, once we sort of decided on the sequence, like vignettes first companioning, with chapters, it all sort of fell together very nicely. And our conference/ conversations produced kind of an implicit agreement about the topics that have to be covered. So the 10 chapters, 10 substantive narrative chapters, covered those subjects that we determined had to be covered. There were other topics that we could have covered. But we didn't have the word count, that, you know, permitted us to go there.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:11

Yeah, this could have been like a 10 volume work, but I it's, it's wonderful, what the sort of breadth of topics you are able to cover within the word count that you're looking at. One of the things and one of those sorts of topics, ideas, I wanted to talk through some, Judy, you talk a lot about intersectional feminism, and of course, you know, this starts way before Kimberly Crenshaw is using the word intersectional feminism, but you're talking about how that's sort of the guiding principle in in Patsy Mink's work and in her life. So I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that sort of how, how you see that intersectional feminism working along her career?

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 19:55

That's a really wonderful question. And I think there's some so many things about Patsy Mink that are exceptional, that she's often forgotten in popular culture and historical narrative, and the reason she gets dropped out of the historical narrative. And first of all, I think our the way we imagined feminist icons is very much along the lines of white and Black, and for someone to come from Hawaii, to the halls of Congress is sometimes beyond the political imaginary for a lot of Americans. And in fact, when she was going to school on the continental United States, she would often be regarded as an international student, even though she was a US citizen, and even though she had grown up in a territory of the United States. I think also the fact that she was a she was in the mainstream of politics. She was in electoral office is also a little bit beyond the scope of people's imaginations when they're thinking about social movements and about radicalism. And so I think talking about her life, really challenges the way we think about feminism, challenges the way we think about politics, challenges what we think about race, but that's what she brought with her to this. She had this intersectional understanding about class, about race, about gender. And it's something that's really deeply ingrained because of who she is, a third generation Japanese American who grew up in Hawaii. Those social hierarchies were very much present in her life, coming from a plantation society, coming of age during World War II, the Cold War, early Cold War, as a woman who was trying to try to enter medical school, to try to become a working lawyer. Right? Those personal experiences shape the type of politician she becomes, shapes the political vision that she has about what the law can do to try to open up avenues for people who are marginalized.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:47

Wendy, you use the term I was familiar with, intersectional feminism, but you used a term that I hadn't heard before, which is topic extinction. And I wonder if you could sort of talk about what what that means in the way you see that that topic extinction playing out and being important?

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 22:05

Well, I borrowed that concept from a former colleague of mine at UC Santa Cruz, Aida Hurtado, who first deployed it in writing about Chicana feminism, I think, probably in the 1980s, or 1990s. The way I deploy the concept is as an as a method of erasure, really, of displacement of the voices of women of color, when they bring up issues. And it can manifest in different ways. It can be sort of a white male taking over the issue and claiming ownership and thus displacing the perspective and the experience and idea that is contributed by the woman of color or the movement of women of color that puts the topic on the table in the first place. Or it could be just not listening at all, so that there's a complete silence assigned to the perspective and so forth. And we see that happening, especially as in in the course of the 1990s, as the numbers of women in Congress and women of color in Congress increase. There's this way in which women are, the women members are, they all obviously are strong and articulate and and fighters, but there's a way in which they are looked upon as troops in a, you know, sort of mainstream Democratic Party fight, as opposed to people who can shift the discourse, who can stretch the boundaries of what policy ought to consider, and, and so forth. We saw that a lot with welfare politics, and we saw it in other aspects of sort of gendered understandings of social justice issues and civil rights issues and the like.

Kelly Therese Pollock 23:57

One of the things, and Judy, you just brought this up too that, that was so interesting, I think, in reading this is thinking about the, the sort of strategy of politics for Patsy Mink, and that's both sort of being outside and inside at the same time. And so being willing to stand up to her own party, to her own colleagues, and in times, you know, facing backlash for that, but at the same time understanding when and how to compromise so that legislation actually gets through. So I wonder if you could both reflect on that a little bit, sort of what what that looks like and, you know, maybe some examples of how that plays out the you know, sort of being both willing to stand up but uh, but also knowing sort of how to how to get legislation actually through.

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 24:51

Well, I think it was always kind of a, I don't want to say dance. It's something sort of politically challenging to figure out out exactly when sort of coalitional compromises were necessary to get, get something through versus when standing your ground was necessary in order to advance the notion for the next cycle of debate that might ensue five years down the road, 10 years down the road and the like. And over the course of my mother's legislative history, I think you see her doing both things. Sometimes when the window for winning on a social justice, it, let's just say, as an example of social justice issue is, you know, barely open, the thing that she would decide to do is to stake out the clear position, and sort of push the envelope for the next round, so that there's a legislative record of, you know, sort of different forms of thinking or different perspectives on on issues, and so that the groundwork kit, you don't have to invent out of whole cloth the next time, the issue is confronted. In the 1990s, I think that there, when it looks less possible to accomplish, what social justice forces, progressive forces wanted to accomplish, because of neoliberalism and the nature of the Clinton Democratic Party, and so forth, it was more necessary to cobble out some victories along the way, because you could actually materially improve people's lives in smaller ways than the big picture that you were actually seeking to accomplish. I think the two periods in which she served, the 60s-70s and the 90s to 2002 offer very different contexts for approaching political strategy basically, about how to proceed but always the goal in mind of figuring out the best way to move toward the just objective, right? It, it may not be the same way in one epoch as it is in another. But the the general goal of reaching towards justice was always a motivating factor.

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 27:18

I really like Wendy's response. I think most people think about politics as exclusively about compromise, and about compromising right positions. And what I really respect about Patsy Mink, is that she was willing to state the principles, to stick to what she believes is just. I talk about this a lot, but there's a great documentary about Patsy Mink called "The Head of the Majority." And that phrase is from a speech that she gives when she runs for the Senate. She loses that election, but she talks about how you need to be politically courageous, and not wait for something to be safe and popular to support it. And so I see that repeated over and over again. And when Wendy was talking about the 1990s, I remember talking to Wendy, like they did not have the votes to reform welfare, along the lines of trying to eradicate poverty, not along the lines, which was the political dominant discourse at the time of punishing people who are impoverished, right, especially women with children, predominately women color with children. And I was just interested in you know, why did they fight so hard, even though they knew they could not win. They just not have the votes. And I love Wendy's response, which is that you need to have this record of opposition, that you need to show that people thought differently about this. And I respect that so much of Patsy Mink and her allies over and over again, they were going to take that position of principle. What I think also is very interesting is that regardless of what she actually did, people perceived her in that way. So, you know, her, her male colleagues would be like, "Oh, she's not kind of playing the game. Like she's being too strong, she's being too inflexible." And partly that's in response to her, but I think it's also male responses to women who are in positions of leadership that there's certain fear about them occupying that status. And then the final thing, I'll just say that, I've been doing more work on the National Women's Conference, and Mink and Bella Abzug co-sponsored that legislation. It was the first and only time that the federal government gave money to create the possibilities of a national women's agenda. And there, I see a lot of respect between Mink and Abzug, who were very close friends and Mink even was working behind the scenes trying to advocate for the most amount of resources. But she also wanted to give Bella credit. So she would say, you know, it doesn't have to be public, right? This can just be behind the scenes, I can help work for this. So I see that she's being very politically savvy and she's also being very politically respectful of people that she that she trusts.

Kelly Therese Pollock 29:59

I'd like to follow up on that a little bit because I think there's this sort of popular conception of second wave feminism as sort of women all out for themselves and sort of pushing each other down to get ahead. And that's clearly not what is going on here. You know, there's this great sort of sisterhood that you're able to talk about with, with Bella Abzug with Shirley Chisholm, and then later with Maxine Waters, and Nancy Pelosi, and it's just sort of incredible to see these connections and these women supporting each other. Could you talk about that a little bit? Because you, Judy, you go back to that several times, as you're writing this book and talk about the ways that they are working together, they may not always agree on everything, they might not always vote exactly the same way. But that they are working together as a coalition to get things done.

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 30:53

Yeah, I was really interested in some of their personal relationships. And I don't necessarily know if they were that close personally. But they definitely allied with each other politically. And so I think there's various times in which they come together and work together as a group. And that that becomes formalized later on in terms of a caucus. But one of the things I really emphasize about Patsy Mink, is it she is in mainstream politics. She's in electoral politics, but she's in conversation and dialogue with social movement activists. And so she's talking to them about what would be ideal policies to pass. And sometimes she doesn't actually even agree with some of the policies, but she thinks that those groups need to have that space, right? They need to have their ideas aired, and given full consideration. So I, instead of seeing her and other women in Washington, DC as outliers, they're really working in conjunction with people who are grassroots who are forming organizations who are trying to think about how can law be an avenue, a tool as part of a broader broader movement towards justice.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:59

And Wendy, then you got to sometimes be that that sort of outside voice a little bit, talking with your mom regularly, working on collaborative efforts from sort of outside inside, could you talk a little bit about that, and about the conference on welfare that that you joint-hosted?

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 32:18

I guess I was in conversation with my mother and my father, throughout my life, about politics and political issues and so forth. At some point, at some point, I became an adult. And, and the discussions were not just the sort of exchange of opinion and the fleshing out of analyses, but also an exchange of expertise from multiple vantage points. In the 1990s, I was, I had been working historic on historical questions having to do with the gendered and racialized gendered formation of US Social Policy in the first half of the 20th century, and then moved on to doing work on how those policies continued, and the politics surrounding them continued to enforce the inequality of marginalized women in the latter part of the 20th century. And there were other scholars who were working in similar, a similar vein, and we were all in conversation with each other as well. So as the whole sort of welfare reform bandwagon that entered into the political mainstream of Bill Clinton's election in 1992, started to become a reality as a policy proposal, feminist scholars, welfare rights activists, and community artists and intellectuals who were concerned about what the punitive politics affecting women was going to end up looking like coalesced and articulated agendas. And I carried those agendas into conversations with my mother, who had her own independent analysis that was however very similar to the ones that we academics were were beginning to espouse, and given the convergence of critical concern for the damaging consequences of Clintonian welfare reform, for women's equality, for women of color, for the whole concept of maternal sovereignty, and, and so forth. We decided to hold a conference that would foreground, spotlight those ideas to show the ways in which welfare reform was a women's issue. It was about women even though nobody was willing to talk about it as a question that should be of concern, you know, first and foremost were its impacts on women and women's equality. And so in combination with the Institute for Women's Policy Research, we decided to hold a conference in 1993, in the fall of 1993, in anticipation of the proposals that would come from the mainstream Democratic establishment as well as from the Republicans. And that was a sort of threshold event that helped to see additional political activity that lasted up to the early 2000s, first in opposing welfare reform policy as it was evolving under Democratic and Republican auspices, and then to try to change it once it was implanted in public policy, to restore the possibility of equality and, and ending poverty for low income mothers and their kids.

Kelly Therese Pollock 35:51

I want to make sure to highlight the importance of local politics too, so I think it's pretty unusual as far as I can tell, for someone to go from being in federal office, then to being on a city council, even for a very big city. And that's such an interesting move. And so it seems so important to understanding sort of who Patsy Mink is and what she's trying to accomplish. So I wonder if we could reflect just a little bit on that, on on her move from Congress, and then when she loses the race for the Senate, being on the Honolulu City Council.

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 36:28

Actually, I really love that period of her life, and maybe because also I'm middle age. So when she leaves Congress, I think she's at this moment of trying to think about what is next for her. It's been a very, it would have been a very fruitful and exciting political life. But what's next on her trajectory? And she does spend time in the State Department and she also leads the Americans Democratic Action. So she's not going back just to be in Honolulu. But what motivates her is that there is a trash burning plant that would be that was being proposed to be located in her neighborhood, and people were concerned and outraged about the environmental implications of that. And so put on the working class, lower middle class neighborhood, racially diverse. So those communities tend not to have a say on what happens in their in, in their community. She worked with local activists, and then decided that city council was actually very important. And she ran for the office. So it just shows to me how consistent she has she is, was as a political activist and political visionary that she was didn't matter whether it was halls of Congress, or halls of city council, she was going to push for environmental justice, she was going to advocate for childcare, she was going to try to find ways to address homelessness, she was going to advocate for transparency into the democratic processes. It just really showed who she fundamentally was. And I love some of the local reactions to her. I don't know if we can swear on the show. One of my favorite quotes is like, "She doesn't take shit from anybody." Right? You really see that that strength and that type of political commitment.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:49

So I do want to make sure we talked about Title Nine, because it is so important and such a monumental achievement. So I am just young enough that Title Nine has been around my whole life and I don't know the world without Title Nine. Can we talk some about the how, how hugely important that is in, of course, people think about women's sports, but women's access to education more generally. And why this was a signature issue for Patsy Mink.

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 38:47

It's a combination of factors, starting with her own personal experiences of exclusion in education, on the basis of race and gender, are sort of part of the process of developing an analysis for her I think, as a territorial and state legislator in the late 1950s and early 1960s. She took a great interest in education policy, in the sort of, in this case, classical liberal, New Deal, liberal kind of fashion. She saw education as a gateway to opportunity or education should be a gateway to opportunity, but obviously could not be if people were being held out, held back, kept out on the basis of descriptive factors. When she first got to Congress, the first sort of comprehensive or first large national investment in public education was on the table, the Elementary Secondary Education Act. So education, sort of the concept of the federal government, kind of articulating priorities with respect to education was also on the table, so it was a milieu that made possible the raising of equality questions with respect to educational opportunity, educational access, educational resources, and the like. Over the course of the 1960s, dealing with a lot of Great Society issues were on poverty issues, which her committee which was the House Education and Labor Committee dealt with, as the authorized committee. She encountered so many programs that were really sort of tailored to men, educational programs, skills training programs, vocational programs that were really tailored to men and grew increasingly frustrated about the sort of general universe of education being a universe in which gender socialization and the exclusion of women was sort of second nature. And so out of that legislative experience, policy observations and the like, in conjunction with the emerging women's movement, and the women's movement's claims to equality in the educational arena, the employment arena, and so forth, emerged this kind of fever of activity, to figure out ways to create legal or policy weapons that women could deploy to accomplish equality. One of those was the Equal Rights Amendment, which is also coming along at this point in terms of being actually voted for, voted and passed through Congress. And the other major one is what becomes Title Nine, which initially begins as a as the concept of prohibiting discrimination in educational programs where the federal government has invested its assistance. The several vehicles are discussed over the course of I'd say '69 to '71 period. And it finally lands in an omnibus bill in 1971, as the ninth chapter, Title Nine, promising this this new opportunity for girls and women to claim equality, even if it's going to take hard work to actually get there.

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 42:22

Maybe I'll just add a couple of things. One is that for the 30th anniversary of Title Nine, Patsy gave a very powerful speech, and that was the year that she also passed away. And she talks about how she's so proud of Title Nine that this is one of her greatest political achievements. But that also that there were various efforts to try to weaken it. And certainly, you see that in the aftermath of that the passage of Title Nine, just different educational athletic interest writing in either different ways that they can dilute the legislation. And so she really broadcasts a message that we have to be vigilant as, as citizens, as people who are politically aware that we need to protect these games, that the law might be there, but the meaning of the law, the implementation of the law, that really comes from all of us to make sure that those principles are actually carried out. And then the other thing, I guess, I'll say, is that when Maxine Waters was giving a memorial speech about Patsy, she talked about how they went to the WNBA game earlier together, and that she looked at these really strong, tall women and how they were able to achieve their dreams of, you know, being athletic stars, and, and that it really, a lot of it was a result of this very small woman. So I love that kind of physical contrast. But Maxine Waters also talked about the fact that it was not just sports, it was all aspects of our educational experience from admissions, scholarship, housing, employment, right, the the campus climate. And so even if Title Nine is not, has not been enforced, to the degree that it should be, that it at least provides the legal principles, I think when we talk about needed thresholds, right of what our expectations are in terms of gender and educational experience.

Kelly Therese Pollock 44:14

Of course, as you were saying, being vigilant as citizens, we can't escape the fact that we are speaking just days after the draft opinion leaked, where, you know, Justice Alito is saying that they're gonna strike down Roe v. Wade, and Casey V. Planned Parenthood. So, you know, I wonder, you end the introduction, Judy, by saying, "Mink was a lifelong fighter who demanded social justice, a remembrance of her determination to speak truth to power will hopefully inspire us to do the same." And so I wonder if maybe, you know, I've thought past few days, like, what would Patsy Mink be doing and saying and fighting for today? So I wonder if maybe we could just reflect a little bit on on that and how we can sort of draw inspiration from her example for what to do in the fight ahead.

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 45:03

Mink was obviously someone who was committed to reproductive choice for women. And I am going to talk about something that's fairly personal that affects Wendy as well. But one of the reasons why she was so committed is that she herself was subjected to medical experimentation, when she was pregnant with Wendy. She was exposed to DES, and at the time, this synthetic hormone was seen as potentially helpful for pregnant women to help alleviate miscarriages. But there was a medical researcher who didn't believe that was the case, wanted to run an experiment to prove that and exposed some women to DES and exposed other people to a placebo. And DES has had long term impacts on people's lives, not just the mothers, but also their children. So there are DES daughters and DES sons. It's been associated with higher incidence of cancer, and it has had long term reproductive implications for the children who have been exposed. So it's something that was deeply personal to both Patsy and Wendy. But I think it just underscores the need to have respect for women's bodies, to have respect for their ability to make decisions about their bodies, and that there's deeply personal implications for these types of decisions. And they should be made by the women who are whose bodies are most impacted.

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 46:28

Yeah, as for what she would say, in terms of strategy going forward, I think, three days after seeing the draft opinion, I'm not sure she would have a finely developed strategy. Frankly, I mean, it's a it's a period of deep darkness. In the early 1990s, of course, people were nervous before the Casey decision was rendered, that the court would take that case as an opportunity to severely roll back if not rescind the key elements of of Roe. And in that context, not only did they engage the fight over the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court, but they also tried to get a hearing for the Freedom of Choice Act, which was intended to codify Roe versus Wade. The Democrats then and it would appear the Democratic Senate now were not able to mobilize majorities capable of enacting such a statute. I'm not sure, given the scope of the Alito opinion, the draft opinion that a statute is a sufficient answer to the withdrawal of rights. So I don't know. I mean, I know that she would want to, you know, she would be she would be brainstorming with people about to figure out the best way forward in these circumstances. But I don't think that ever, I don't want to speak for her. But I think that she would agree that the the answer to our current very dark dilemma is not self evident, that we're going to have to be politically creative, because the ramifications are so profound, and take so many different forms from the potential definition of abortion as homicide in Louisiana, which is happening right now in the state legislature, punishing people who go out of state to exercise their abortion rights, and so forth. So I don't have anything conclusive to say about what she would want to do necessarily, other than fight on, stand up, fight on, stand in solidarity with everyone who is going to be injured by this ruling.

Kelly Therese Pollock 48:55

So just like the book could have been 10 volumes, this episode could be 10 parts, but we're gonna wrap it up now. And people should just go buy the book and read that. So can you tell everyone how they can buy the book?

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 49:09

Well, hopefully they can buy the book at booksellers everywhere, or at least they can ask their local bookseller to order it for them. It's also available at online sites, vendors of books, I won't name the main one that people go to, but it's there. And it can be ordered through the publisher, New York University Press, NYUpress.edu.

Kelly Therese Pollock 49:34

Excellent. Is there anything else that either of you wanted to make sure we talk about?

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 49:39

Thank you so much for the opportunity. I really appreciated the questions.

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 49:44

Yeah, thank you very much.

Kelly Therese Pollock 49:46

Well, I am so thrilled that you both spoke with me and that you wrote such a beautiful book. It has been very inspirational to me and I hope that other people will will pick it up and read it. I think it is It is too bad that Patsy Mink doesn't get more recognition and more celebration, and I hope that your book will change that. So I really appreciate it.

Dr. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu 50:09

Thank you so much, Kelly.

Dr. Gwendolyn Wendy Mink 50:11

Thank you.

Teddy 50:13

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Judy Tzu-Chun Wu is a professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Irvine and the director of the Humanities Center. She specializes in Asian American, immigration, comparative racialization, women's, gender, and sexuality histories. Wu received her Ph.D. in U.S. History from Stanford University and previously taught at Ohio State University. She authored Dr. Mom Chung of the Fair-Haired Bastards: the Life of a Wartime Celebrity (2005) and Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism, and Feminism during the Vietnam Era (2013). Her book, Fierce and Fearless: Patsy Takemoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress (2022), is a collaboration with political scientist Gwendolyn Mink. Wu is currently working on a book that focuses on Asian American and Pacific Islander Women who attended the 1977 National Women’s Conference and co-editing Unequal Sisters, 5th edition. She co-edited Women’s America: Refocusing the Past, 8th Edition (2015), Gendering the Trans-Pacific World (2017), and Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies (2012-2017). Currently, she is a co-editor of Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000 and editor for Amerasia Journal. She also serves as chair of the editorial committee for the University of California Press and as a series editor for the U.S. in the World Series with Cornell University Press. She is the co-president of the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians.

NEW in 2022: Fierce and Fearless: Patsy Takemoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress (NYU Press)