The National Women's Football League

In 1967, a Cleveland talent agent named Sid Friedman decided to capitalize on the popularity of football in the rust belt by launching a women’s football league, which he envisioned as entertainment, complete with mini-skirts and tear-away jerseys. The women he recruited had other ideas, and soon they were playing competitive tackle football, not in skirts but in football uniforms.

In 1974, the owners of several teams around the country, some from Friedman’s WPFL and some independent of it, formed to create their own league: the National Women’s Football League, the NWFL, which started with 7 teams and grew within a few years to 14 teams across three divisions. The league faced financial difficulties from the beginning and finally folded in 1989, but the desire of women to play professional football lives on.

I’m joined in this episode by

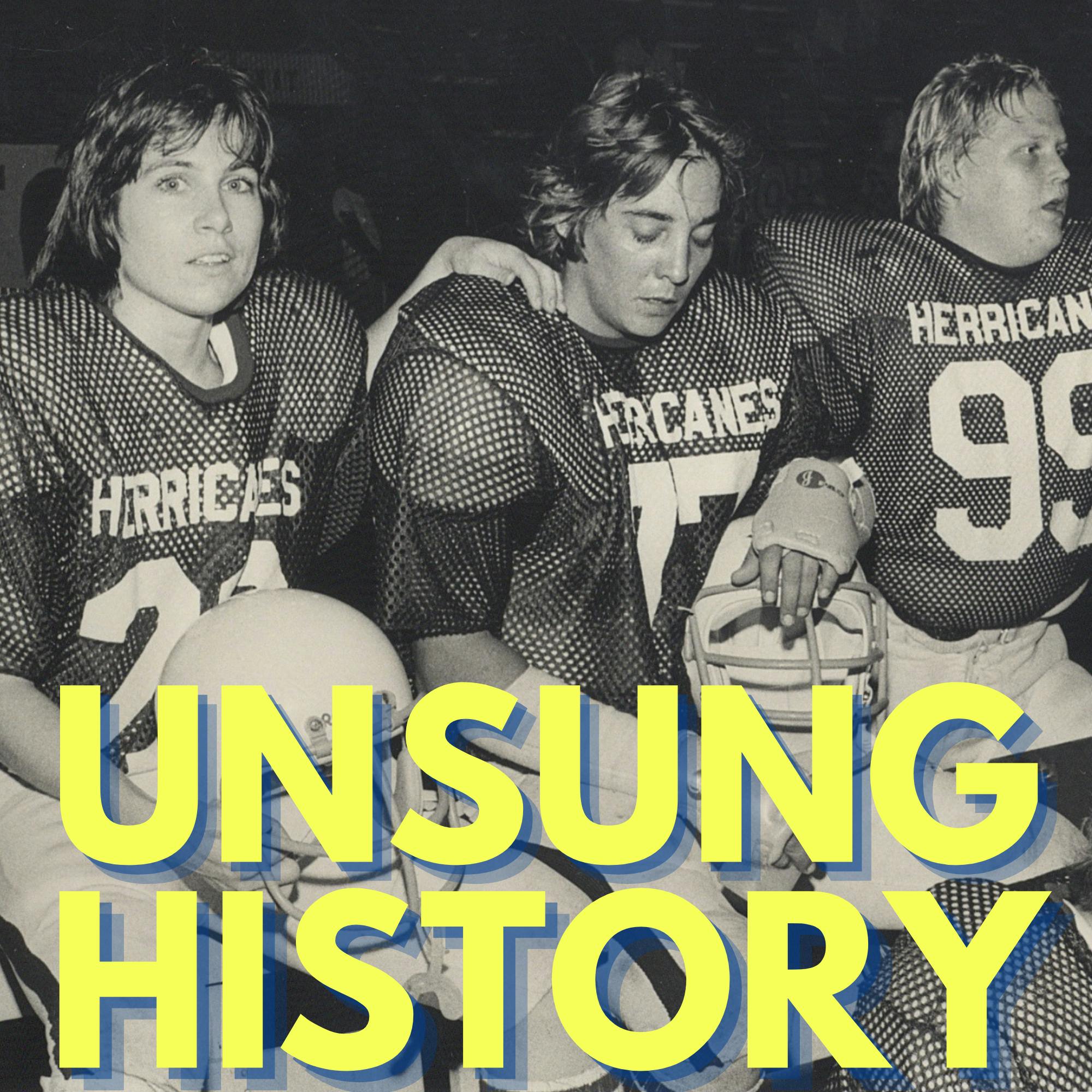

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. Photo Credit: Brenda Cook, Brant Hopkins, and Baby Murf, Houston Herricanes. January 1979, Safety Valve, Published Monthly by Houston Natural Gas Corp., original photo provided by Brenda Cook, Houston Herricanes.

Additional Sources:

- “Revolution on the American Gridiron: Gender, Contested Space, and Women’s Football in the 1970s,” by Andrew D. Linden, The International Journal of the History of Sport (2015), 32:18, 2171-2189.

- “The Unusual Origins of the Dallas Bluebonnets, the Trailblazing Women’s Football Team: An excerpt from the new book Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women's Football League,” D Magazine, November 2, 2021.

- “Remembering Toledo’s Troopers: Film to tell story of ’70s female football team,” by Tom Henry, The Blade, June 16, 2013.

- “Almost Undefeated: The Forgotten Football Upset of 1976: How the Toledo Troopers, the most dominant female football team of all time, met their match,” by Frankie de la Cretaz, Longreads, February 19, 2019.

- “How sexism and homophobia sidelined the National Women's Football League,” by Victoria Whitley-Berry, NPR Morning Edition, November 3, 2021.

- “The Forgotten History of Women’s Football,” by Erica Westly, Smithsonian Magazine, February 5, 2016.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. On today's episode, we're discussing the National Women's Football League, NWFL. American football is still today, seen largely as a men's game, but women have played nearly since the beginning. The beginnings of American football trace back to the late 19th century, when a number of elite New England universities started to play a mix of soccer and rugby. Walter Camp, who was a Yale undergrad and then medical students in the 1870s and 1880s, played on and coached the Yale team. And he shepherded the rules board of the Intercollegiate Football Association, the IFA, becoming known as the father of American football. As early as 1896, women were playing football at Sulzer's Harlem River Park in 1896, a group of women played what was expected to be a light and gentle version of football for men's amusement. But the women had other thoughts. The game was rough enough that the police came to shut it down before anyone could get hurt. Men continued to think that women should play football for their amusement, and women continued to want to actually play. In 1967, a man named Sid Friedman came up with the idea for a women's football roadshow, like the Harlem Globetrotters. Friedman was a Cleveland talent agent, and for him this was designed as entertainment, not athletics. He originally envisioned the players wearing miniskirts and tearaway jerseys. The four teams that formed the Women's Professional Football League were the Cleveland Daredevils, the Pittsburgh All Stars, the Canadian Belles from Toronto, and the Detroit Petticoats. Between 1967 and 1973, more teams joined the league, some lasting only for a short while, and for a time, the WPFL was divided into an East and West Division. The WPFL games were, as Friedman intended, largely exhibition and charity games, sometimes played during halftime shows for the NFL or CFL. The teams did play a small number of actual games each year as well. Eventually, several of the teams wanted to break away from Friedman's League. In 1974, a group of owners of teams around the country from within and outside the WPFL met in California to found the National Women's Football League, the NWFL. It started with seven teams: the California Mustangs, the Columbus Pacesetters, the Dallas Bluebonnets, the Detroit Demons, the Fort Worth Shamrocks, the Los Angeles Dandelions, and the Toledo Troopers. By its third season, in 1976, the league had 14 teams organized into three divisions. The league was led by President Bob Matthews, three divisional vice presidents and Executive Director Joyce Hogan. Sid Friedman was not included in the NWFL. Each team in the league had to pay a franchise fee, which was originally $10,000 and went up to $25,000 the next year, and players were to be paid $25 A game. All of the teams in the league lost money. Ticket sales were never enough to cover the cost of travel, uniforms, equipment, and stadium time. This isn't unusual for new professional leagues. The first decade of the NFL was a failure too.

The difference is the extent to which owners were willing to pour money into the NFL teams until they did start making it back. The official rules of the NWFL included 12- minute quarters and a smaller football than regulation NFL footballs. In the NWFL, unlike the NFL, a kick after a touchdown was worth two points, while a run or pass play after a touchdown was worth one point. The Toledo Troopers, led by the league's star player Linda Jefferson, and the Oklahoma City Dolls, which were founded in 1976, were the two best teams in the league, facing off in the championship games in three consecutive years. In 1975, Women's Sports Magazine named Linda Jefferson, their first ever Woman Athlete of the Year. The 1970s were a boom time for women's sports in America. With the 1972 passage of Title Nine and Billie Jean King's win over Bobby Riggs in the September, 1973 Battle of the Sexes. But by 1979, many of the original teams in the NWFL were folding because of lack of funding. New teams were still forming. Throughout the 1980s, teams continued to form and fold, but they all faced financial problems, and the media never gave them a lot of attention. Finally, the league ended in 1989. The only team to last for the entirety of the league was the Columbus Pacesetters. Around 19 teams in total played at some point during the league's history. Since 1989, as many as a dozen football leagues for women have started and folded, facing many of the same challenges that the NWFL did. There are currently four women's football leagues: The Women's National Football Conference, WNFC, the Women's Football Alliance, WFA, the United States Women's Football League, USWFL, and the Women's Tackle Football League, WTFL. Joining me to help us learn more about the history of the NWFL are Britni de la Cretaz and Lyndsey D'Arcangelo, authors of "Hail Mary: the Rise and Fall of the National Women's Football League." Hi, Lyndsey. Hi, Britni, thank you so much for joining me today.

Frankie de la Cretaz 7:53

Thanks. Thanks for having us.

Kelly Therese Pollock 7:54

Yeah, so, I wanted to start just by asking how the two of you even heard about the National Women's Football League. I was thinking as I was reading your book, I grew up very near Canton, Ohio in the 80s and cared a lot about you know, equality for women. And I had never heard of this, which seems pretty tragic. So how did you hear about the league? How did how did you become interested in writing about it?

Frankie de la Cretaz 8:20

Yeah, so Lyndsey, and I actually heard about the league when we were researching different, much broader project about women in football. This is our second attempt to write a book about women's football history. Our first one didn't sell. It was, you know, much less narrative, much less focused. And in the process of researching that we discovered this league. We came across them through the Toledo Troopers because they are the most well known team in the league. Being the winningest team in pro football history, there is the most information available about them. And once we started to dig into more about who they were playing, and what that was, like, we realized how much must be there and how little was actually available. And it became very clear very quickly that this league was actually the story that we wanted to tell.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:19

Yeah, it's a it's a fascinating story. So talk to me some about how, you know, you said there must be information out there and there is and you discovered a lot of it, but there's so much information that's missing. So for a professional football league, you know, you'd expect like archives of material and you know, and there's so much that's missing. So what was your process about, you know, for going about finding out what you could about the league and figuring out where the gaps were?

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 9:47

Well, there wasn't a lot of information available on the on the internet. We actually got a lot of player leads and info on on the different teams and games through old newspapers. We just started with researching old newspaper archives, and around that time period, looking up different teams, looking up the National Women's Football League. And then once we started getting names of players, we were able to, you know, write those names down and then reach out to those players through, you know, cold calling, or Facebook. They're all in their mid to late 60s, early 70s, so some of that was a little difficult. You know, you're coming back around after 40 some years to say, you know, I want to talk about the football league you played in, the Los Angeles Dandelions or whatever team. Britni and I also split the teams down the middle. So Britni took some and I took some, and then we focused on the players for those teams. So so that was helpful as well, as far as, you know, working together to get as much information as possible. But really a lot, a lot of the information we were able to get came from the players themselves through memorabilia that they saved, whether player programs, ticket stubs, their own their own notes, I remember one player for the Houston Hurricanes supplied me with an invoice that she saved from when she bought her equipment for the first time, things like that. That was very helpful and give you an inside view of, of the league and what it was like, not having stats to really dig into. The NWFL, the owners and the league heads didn't really do a great job of keeping stats season over season. So that was part a big part that was lacking. But yeah, most of it came from our old newspaper clippings.

Frankie de la Cretaz 11:45

Yeah, and I will say this, this is a History podcast, and people probably are like nerds about this stuff. Part of our job is, you know, taking a player's faulty memory, taking a newspaper article and taking a game program or like a list of season game scores, and trying to like put the puzzle pieces together to find out what the actual truth might be. In the book I wrote about a fight between the Toledo Troopers and the Detroit Demons. And it took me two years to piece together which game the fight happened during because there was a newspaper article about the fight. But they'd played each other two times that same month. And so I had player memories that thought they remembered what, what had happened around the games. And it did, it took two years. And finally, because the newspapers wanted to promote the fight, and not the game, I never knew the score of the game. And I think I got it right, I could have gotten it wrong. But like that was a two year long project of piecing together newspaper clippings and stats and player memories to try to see if we could find out what the score of that game was. And so that's what a lot of that research process was like.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:03

Yeah, and it's not just the scores or how many yards people rushed or something like you don't even know for sure what the records of these teams were. Even the Toledo Troopers, the winningest team, there's this sort of disagreement about how many games they might have won or lost. Why Why weren't there better records kept? You know, what, what was it about this league or about women's sports in general at this time, that that meant that people weren't keeping better records?

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 13:34

That's a great question. And one we have yet like, I don't remember anybody asking us that as of yet. And it really is a good question, as far as stats go. I think, you know, the, the, the the people who put the league together, and then the league owners that ran teams, some individual teams did a lot better than others. The Toledo Troopers actually kept season records and stats. But there were other teams that were player-run, that maybe didn't or that were owned that by an owner who didn't, I don't know, maybe value that or we just never came upon it. There could have been stats kept by these teams that we just were unable to discover. As far as the league goes, I think it was just a lack of foresight, you know, to really, to really grasp what they were doing at the time and how maybe how historic it was and how a crucial part of their whole story it is and to have that physical, you know, evidence that you know, they played and then this is how they did that and you know what teams did really well and other teams that maybe struggled a little bit but also it would, you know, give the players some credibility too, to get as their you know, in physical form. But yeah, I'm not I'm not really sure. I don't, Britni might have some insight into that. What do you think Britni?

Frankie de la Cretaz 15:00

I think that people like, so there was, right, no centralized structure here that was tracking these things. And most of these people had never run a team before. So it may not have crossed their mind that these were things they should have been keeping track of. My guess is there probably is like a coach or a player on each team that did keep that, but how whether they were with the team the whole time, you know, you don't know. I will say, the Columbus Pacesetters, which is the only team that ran the length of the entire league, their last season, which was their 15th anniversary, they have like a yearbook program. And it has the like MVPs, and like leading rushers and everything like that for each season. And what I, the reason I think they have that for every season is because there was a player named Andie Dameron, who played from the first season in '74, and by '88, when their 15th anniversary was, she was a coach, and she stayed with the team the whole time. And so you have that continuity, and somebody that cared enough to like, keep track of all of that. But if you didn't have that, I think it just wasn't even on anybody's radar. And so you have to leave it to the newspaper reporters who maybe are showing up, maybe are not.

Kelly Therese Pollock 16:17

So I guess maybe that leads to to a question that I have, which is, what is the nature of "professional" in professional sports? So this is a professional sports league, but these women were not making their living as football players. Most of them had full time jobs, or they were stay at home moms or something. So what what is it that makes a sport professional, a league professional? And what does that mean for the players, for the league, for the teams?

Frankie de la Cretaz 16:45

I think that what made this professional was that the women were going to get paid. And they sort of did for a little while, they got $25 a game, and eventually that money ran out. But the idea of being professional means that you're getting paid to play. And so the reality, though, as you said, is when you look at this league, the skill level was probably a lot more like a very good high school team, because the women didn't grow up playing football and are learning the sport as adults. So it's not necessarily what people think of when they think of professional football. And again, that's not a talent gap, that's an access gap, that when given the resources and time in training, the women are very capable of playing at that level, and many women today do. And then they, you know, they were like selling raffle tickets to pay for stadium time and stuff like that. But it is it comes down to the fact that they were in theory getting paid to play.

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 17:49

I also think there's a connotation to the word professional, right? It adds legitimacy. So in that way, I think referring to themselves and their owners referring to the league, some of the team owners referring to the league as professional, you know, that adds an amount of credibility when they were trying to, you know, establish the league and and keep it going and grow. So that's the other side of it.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:17

Did the fact that this was professional, cause problems for any of the women who maybe played other sports? I know there's very complicated still, but especially back then, very complicated, sort of, what does it mean to be amateur, professional? And you know, can you get yourself in trouble doing amateur other sport if you're professional in this sport? So did that come up for these women?

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 18:38

Yeah, there was a player on the LA Dandelions named Rose Low, who was very involved in college athletics, especially after Title Nine. She just wanted to try her hand at anything from rowing to archery. And so she she was playing team sports in college, when she discovered the Dandelions and tried out, made the team and had and there was really no guidance at that point, for you know, for what these players were, if could they play on the team? Could they not? She asked her athletic director and got didn't really get a firm answer. So she decided on her own to sit out that first season with the LA Dandelions, just to be sure, because they had you sign contracts to play. And so you know, she just was trying I guess to cover all bases and she didn't feel comfortable. She didn't want to not be able to participate in the college sports. So that first season she did not play with the Dandelions. She was on the team but did not participate in the games or anything until the following season.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:44

So I wanted to ask you both right about sports and gender. Obviously, gender is very important to this story. A lot of these teams were owned by men, managed by men, often coached by men. What is this sort of really complicated gender dynamic that's going on here? Of course, the first teams before the National Women's Football League are, you know, sort of put together like, maybe they're gonna be sort of, you know, wearing skirts or something and showing up. So you know, what, what is this sort of gender dynamic that's going on? And how do maybe different people see it differently as it plays out?

Frankie de la Cretaz 20:24

The thing about this is that we're speaking specifically about football, right. And so there are newspaper articles from the beginning of the league, where they're actually asked why they're being coached by men. And this is because like, now we think of a lot of women's sports are still coached by men. But that actually happened after Title Nine. Title nine, brought money to women's sports. And then once there was money in women's sports, the women got pushed out. But prior to Title Nine, 90% of women's sports were coached by women. And so this was a question that was asked of the women, you know, at the time, "Why are you coached by men?" And the answer there was, because we don't have the fundamentals, yet, we don't know, we've never been given an opportunity to play organized football. And so the people that had the knowledge to pass down were the men. If you look at the league over the course of its existence, what happened is, players did start to switch from player roles into coaching roles. And by the late 80s, most, almost all of the teams are coached by former players. And that's because they gained that that knowledge. And we see that today with the women who are coaching in the NFL that they come often out of the women's semi-pro leagues that exist today. So in terms of coaching, I think that's really you know, why. But in terms of financing, most of the women didn't have the money to bankroll this kind of thing. However, a lot of the men that were bankrolling these teams also didn't really have the money. When we think about team owners, what we think about is NFL owners who have millions or billions of dollars to put into these teams, and franchises and really build them. And that was not the case here. These were men that somehow were like, sometimes were like pooling their life savings of $17,000, or whatever it was to start a league, a team. And thinking that in the course of a few years, they were going to be rolling in it, which is just not how leagues work, either. And most leagues take at least 10 years to be profitable at all. And they're operating at a loss before then. But it is the men who I think, because this is such a male dominated sport up until this time, is really like where it came from. Lyndsey, I don't know if you have different thoughts about that.

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 22:57

No, yeah, you touched on a couple of things that I was thinking. But also, I'd say opportunity, being able to have that opportunity to even play at that time period, you know, where things were men had to create that opportunity. Because if you look at the beginning of the book, we talk all about the history, how about women have been trying to play this game since it was invented. And they just weren't given the opportunity to really do that. And so when that opportunity came along, because of either Sid Freeman, who created those, that group of teams, which you loosely referred to at the start of this question, and then when the lead kicked off started by a group of owners, you know, it was men. And so the they were they created the opportunity. And at the time, you know, women just wanted the chance to play and took it.

Frankie de la Cretaz 23:48

I will say something very interesting that happened over the course of this league, for one team, in particular, the the Columbus Pacesetters, is that they were owned by men, they started being owned by Sid Friedman, who was exploitative, and they decided to leave and be under the ownership group with the Toledo Troopers, which again was a group of men. And after a couple of years, decided they could do a better job running the team themselves, and formed a corporation and purchased themselves from the men. And they actually credit football with giving them the confidence to do that. Because they describe the sport giving them their first experience of having power over someone or something else. And realizing that if they had power over on the field that maybe that power over could translate off the field. And they banded together and did this thing. And I think that's a really beautiful like piece of this history that that shows what the actual what the sport and the experience gave some of these women around some of these like gender dynamics.

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 24:56

Yeah, and that also sort of marked a shift I think and and where, and maybe not just in women's football, but overall, you look at that as being like things were starting to shift where women were wanting to, you know, guide their own sport's future and direction. And I think it was not only inspirational, but yeah, a sign of things starting to shift.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:22

Yeah. So I want to ask some about the experience of writing and writing together. So you mentioned splitting up the teams to look at different teams, you know, but what what does that process actually look like from sort of beginning to end in writing a book together with someone else, which is a very different enterprise than writing a book by yourself?

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 25:46

Yeah, when we, when we met and connected, we actually met in a Facebook group of for sports writers of marginalized genders and Britni and I would always bounce things off. Britni had been freelancing in the space more than I had, at that point in time, I had been doing a lot of print, and writing about LGBTQ issues. So when I'm switching over to sports, and trying to get my foothold there, bounce a lot of questions. And so when we connected, you know, we got along really well, we had never worked on anything together before not an article. So our first task was to write the proposal. And this was for our previous idea, the more broad spread look at women in football in general. And once we did that, and it sort of just meshed together well, I had, I had confidence that we could write together. We both have different strengths. I come from a fiction background. So you know, I do a lot of the spicing things up and the narrative, and I love, I did all the history, I love the history aspect of things, and Britni's more analytical and has just has that incredible way of looking at, you know, something in sports, but really breaking it down from, you know, whether it's regarding gender, or sexuality or just anything, really. So we were able to kind of form this team, where it with our individual strengths. And then our writing style, our writing practice is also different. You know, I'm very, I like to work things bit by bit. I've never missed a deadline in my life. I'm very, very punctual in that way. But yeah, I'm, I'm diligent, and it just flows that way for me. And Britni is somebody who can, you know, just cram out 7000 words in the span of a day or whatever, and which I admired incredibly so. So that I think was it was something we had to sort of adjust. But overall, I think, you know, you never know how well you're going to work together if you've never written with somebody, and we just happen to to have a partnership that that came together really well and worked well together.

Frankie de la Cretaz 28:10

It could have been a nightmare. Lyndsey woke up every day and wrote, and I didn't write anything for six months. And then the week before deadline, I wrote like 25,000 words. I had like half the book done. And Lyndsey did not let on how probably how stressed she was, but she just kept being like, "I've seen your completed work. So I know that whatever your process is, it works for you. And I'm going to trust you." And I was like, "Cool, but you know, deadlines are like suggested start dates for me." But no, it worked. And it could have been disastrous with somebody else. But we did have to sign a like little contract thing with our agent about what would happen if our working relationship dissolved or like one of us didn't hold up our part of the bargain, which was an interesting little tidbit that I think people probably don't think about, but like, yeah, we signed a contract about like, like an agreement about what would happen if if something came up.

Kelly Therese Pollock 29:04

Yeah, that's interesting in the context of writing about team sports, thinking about the team dynamics of writing.

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 29:10

Yeah, this is also a project, too, that I don't think either one of us could have, I mean, we could have done it by ourselves. But there would have been, there would have been part of it just missing. You know, we both provided aspects that just blended it together in certain ways where I think individually, it would have been lacking. Plus, the research alone was was a haul for someone to do by themselves, I think.

Kelly Therese Pollock 29:37

So I wanted to ask about that. We've talked some about sort of the archival and newspaper pieces, but you also interviewed a lot of women. So could you talk about that and you know what, not just sort of what you got from them, but what it meant to them to have someone asking after all this time about the league and what it meant to both of you, too, to have these conversations with them?

Frankie de la Cretaz 30:02

I found that many of the players had, they were waiting for someone to ask. Many of them, we're kind of like, "Where have you been in 40 years? We're so happy women are playing football now. But give us the credit. We were there first." For many of them, they played, you know, just a few years. And they described them as the best years of their lives. I felt incredibly honored to get to do this. It felt like such a privilege and really gift that somehow it's one of those things where as a journalist, you're like, "This is my once in a lifetime sort of thing that you stumble upon. And I don't know how no one has written about this yet. I can't believe I get to be the one that does this." It truly felt like that. And, I mean, personally, though, I will say I was in a really interesting place, around like what I wanted to do with my life. And I started these interviews, and my very first interviews were with women on the Dallas Bluebonnets, many of whom were openly gay. And I found that to be a very significant part of their connection to the team. And like a month after talking to them, I ended up like deciding to divorce my husband. And the women were like, very cute, and some of them knew, not all of them. And they were like giving me pointers on like some of their like, "I've been out for 45 years. Let me tell you." And there was something really like, I don't know, you bond with sources, I think a little bit differently when writing a book than you do when you're writing a feature. There's a lot for me, at least there was a lot less of that like hardened boundary that I usually keep. And so I think the whole thing kind of like hit in a very, like sweet and special spot for me and I yeah, I feel really like lucky. They were inspiring to me. Lyndsey had a different experience with some of her players, though, than I did around like readiness to talk about this because I encountered nobody that didn't want to talk.

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 32:16

I mean, most of them wanted to talk, the players that I spoke to. There was one in particular, Rose Low, who I already mentioned earlier. You know, this was a very personal time, and special time for a lot of these women, and something that they hold very dear to their heart. And for Rose especially, she was a captain, she was involved in the team for a long period of time. It means a lot to her. She to this day, she still tries to keep in touch with the teammate with the teammates, and keep everyone kind of abreast of what's happening in their lives. She she had DVDs made not too long ago about just one of their games that had had been filmed along with an NBC News report that was filmed on TV in the 19, late 1990s. She had put that all together and sent out the DVDs to them, me, to me as well. So she was she wanted to be able,she wanted to trust whoever was doing this, that they were going to do it justice. And so initially, she didn't know who I was, you know, didn't I was reaching out through email, I randomly found her email address. And, you know, she didn't know who I was to put that trust in me. And I had managed to track down a couple of her teammates that she's still in touch with and they said, "You've got to talk to Rose. You've got to talk to Rose." So they spoke to her on my behalf. And then we initially they gave her my number she sent me a text. We initially texted back and forth and finally had a phone call where I still feel like she was vetting me a little bit. And then after that I you know it was the floodgates opened up and she was just ready and willing to supply me with, she mailed me memorabilia and information that was key that we were some things that we were missing and as well as she'd send me care packages throughout the writing process. When we finished the book, she sent me a little gift and recently had sent me something to send Britni. She's just been amazing. But it took you know, it took a little bit of her just really feeling me out to be like "Okay, I think you're I think you're the person to do this. And here we go." She was probably that she was the toughest one, I think that either of us had spoken to. And Gail Dearie was another who she didn't play in the NWFL. She played for the New York Phillies right before it launched, but she was you know, had a viral what we would call a viral moment with a photograph that appeared in Life Magazine. So and she was also very, you know, just kind of hesitant at first like what is this about? But once she got talking, she was happy to chat as well, so, yeah. I don't know why that worked out that way where I kind of, you know, had some hesitant players. But you know, once they started talking, they were they were more than happy to, to have that conversation.

Frankie de la Cretaz 35:14

It's okay, I had the tracking two years to track down Linda Jefferson, because of a catastrophe thing we found. I got her, best player in the league. But so we had different different struggles.

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 35:24

Yeah, that worked out, they worked out. So.

Kelly Therese Pollock 35:28

So I don't want to give too much of this away. So people should buy the book. So tell people how they can get your book.

Frankie de la Cretaz 35:34

Anywhere books are sold, ideally, your favorite indie local bookstore.

Kelly Therese Pollock 35:40

And there's lovely photographs that people should look at, too.

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 35:43

Yeah, we wanted to include more. But we were we were unable to get the rights for some tracking down rights this, this, you know, trying to find the people who took the photograph or so long ago or getting the rights can be pretty expensive. Or just, you know, tracking the people down was almost impossible. So we were unable to include all the photos we wanted to but the ones that are in there are pretty, pretty cool.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:10

Is there anything else that either of you wanted to make sure that we talked about?

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 36:15

I don't think so. I think, you know, this is an important part of women's sports history, sports history in general that I think not many people, I know for sure not many people know about. And it's something that I think needs to get out there and needs to be honored and remembered. So it's well worth digging into and, and learning about.

Frankie de la Cretaz 36:38

Yes, so the one thing which brings me to, we would love to see these women honored in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, which they are currently not. And so I think if there's one thing that this book can bring attention to and recognition to the league, I think that would be very cool. And so that is like an ideal outcome here. Thanks.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:00

As a former resident of Stark County, Ohio, I wholeheartedly agree. I don't know if I have any connections to the Football Hall of Fame, but I'll try to figure it out. Excellent. So final question. Do either of you play football?

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 37:14

I well, not professionally, but I have. I actually not too long ago was playing in a co-ed two-hand touch league that and I just had the most fun. I I love football. I am a huge football fan and a Buffalo Bills fan, born and raised in Buffalo. I used to play with my brothers all the time, you know, and their friends and wasn't allowed to participate in youth football, because of my gender. So finally getting to play as an adult in my 30s was just a joy. I really I love the game.

Frankie de la Cretaz 37:48

I was a cheerleader. So I want to not actually underestimate what we talked about in the book. It's like football culture as a whole. And for a lot of women and girls, their access to football culture is actually on the sidelines and gameday culture and also though to be a cheerleader, you have to know the game, you have to know which which cheers to call and like what's happening on the field. And I think that often they don't get enough credit that they deserve for like, yeah, their involvement and understanding of what's actually happening. And so that was my entry point into into football culture. And I think it was a good compliment.

Kelly Therese Pollock 38:27

Yeah. Definitely. I, the only time I ever broke a bone in my life was playing football. So in college, I played flag football, co-ed IM flag football. And in one one day I was the IM captain and they needed another player for the men's team just so they could like have a body out there. And that's the only time I broke a bone. I broke a finger playing men's football, flag football, not even tackle. So I certainly could never have have done anything that these women in the book did. But I have a small amount of understanding of what that takes and huge, huge respect for them. So Lyndsey, Britni, thank you so much for talking to me about the National Women's Football League. This is super exciting. I wish I had known about them as a kid. I think that might have changed sort of my whole view of football. And I really appreciate you writing this book and talking to me.

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo 39:24

Thank you for having us on.

Frankie de la Cretaz 39:25

Yeah, thank you.

Teddy 39:28

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @unsung__history, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Frankie de la Cretaz

Frankie is a freelance writer whose work sits at the intersection of sports, gender, culture, and queerness. Their writing is a mix between reported journalism and creative nonfiction, and they teach writing classes at GrubStreet.

They are the former sports columnist for Longreads, as well as the former sports and culture columnist for Bitch Media. Their work has been featured in the New York Times, Sports Illustrated, Vogue, the Washington Post, Bleacher Report, The Ringer, The Atlantic, and many others. You can read clips of their writing here.

Frankie is repped by JL Stermer at Next Level Lit. JL can be contacted at jlstermer@nextlevellit.com. Their book, HAIL MARY: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League, is co-written with Lyndsey D’Arcangelo is available now, from Bold Type Books. The book was called “a delight” by Publisher’s Weekly and named one of the Los Angeles Times’ “10 sports books we loved in 2021.”

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo

Lyndsey D'Arcangelo writes about Women's College Basketball and the WNBA for The Athletic WBB and Just Women's Sports. Her first nonfiction book, Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women's Football League is available now.