The National Women's Conference of 1977

In her 2015 book, Gloria Steinem described the National Women’s Conference of 1977 as “the most important event nobody knows about.” The four-day event in Houston, Texas, which brought together 2,000 delegates and another 15,000-20,000 observers was the culmination of a commission appointed first by President Ford and then by President Carter, and was and funded by Congress for $5 million to investigate how federal legislation could best help women. The excited delegates believed that the conference would change history, so what happened, and why do so few people now even remember that it happened.

Joining me to help us learn more about the National Women’s Conference are Dr. Nancy Beck Young, the Moores Professor of History; and Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell, Assistant Professor of Digital Media, who are both on the leadership team for The Sharing Stories from 1977 project through the Center for Public History at the University of Houston.

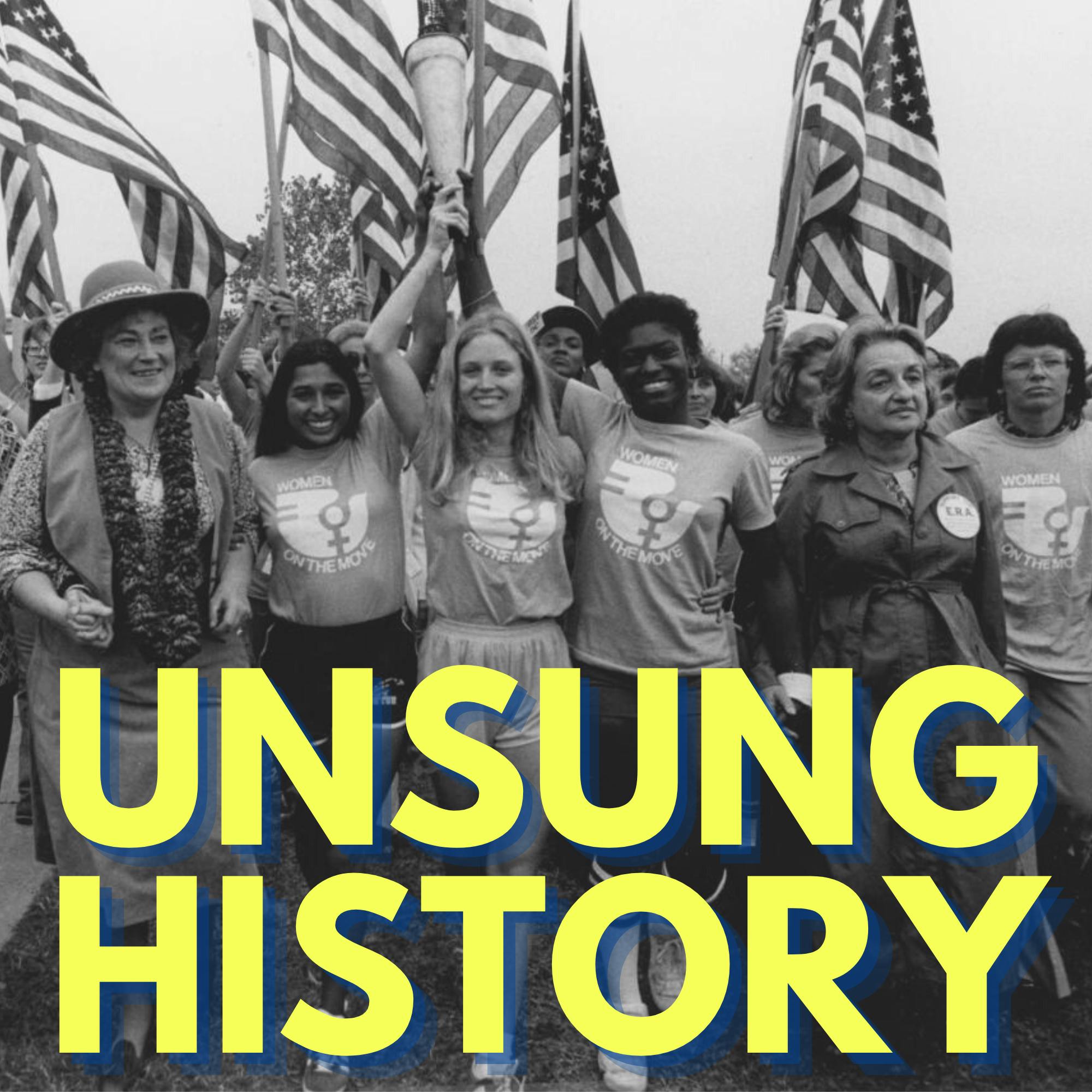

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “Retro Disco Old School” by Musictown from Pixabay. The episode image is from the final mile of the Torch Relay on its arrival to Houston on November 18, 1977. From left to right: Bella Abzug, Sylvia Ortiz, Peggy Kokernot, Michele Cearcy, Betty Friedan, Billie Jean King. Photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Additional sources:

- Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women's Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics, by Marjorie J. Spruill, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.

- “Women Unite! Lessons from 1977 for 2017,” by Marjorie Spruill, Process :A Blog for American History, from the Organization of American Historians, The Journal of American History, and The American Historian, January 20, 2017.

- “The 1977 Conference on Women’s Rights That Split America in Two,” by Lorraine Boissoneault, Smithsonian Magazine, February 15, 2017.

- “Sisters of ‘77 [video],” Directed by Cynthia Salzman Mondell and Allen Mondell, March 1, 2005.

- “Spotlight: National Women’s Conference of 1977,” by Chucik, National Archives, November 16, 2017.

- “Women on the Move: Texas and the Fight for Women’s Rights,” Texas Archive of the Moving Image.

- “National Women's Conference, 1977,” by Debbie Mauldin Cottrell, Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- “The 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston Was Supposed to Change the World. What Went Wrong?” by Dianna Wray, Houstonia Magazine, January 20, 2018.

- “Road Warrior: After fifty years, Gloria Steinem is still at the forefront of the feminist cause,” by Jane Kramer, The New Yorker, October 12, 2015.

- “What’s left undone 45 years after the National Women’s Conference,” by Errin Haines, The 19th, March 25, 2022.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

This week, we're discussing the 1977 National Women's Conference in Houston, Texas. In December, 1961, 41 years after the ratification of the 19th Amendment granted women in the United States the right to vote, and 38 years after Alice Paul had first proposed the Equal Rights Amendment, President John F. Kennedy established the President's Commission on the Status of Women. The Commission, chaired by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, was tasked with investigating discrimination against women in several areas, including education and the workforce, and making suggestions for improvement. The Commission's final report, published in 1963, after Eleanor Roosevelt's death, outlined a number of recommendations to achieve women's equality. But change was slow to come. "Discrimination in public places on the basis of sex" was added to Title Seven of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But it wasn't part of the original proposal, which outlawed discrimination based on race, religion, color, or national origin. The inclusion of sex in Title Seven was made by Democratic Representative Howard Smith of Virginia, the chairman of the powerful Rules Committee. Smith was a supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment, but he likely made the proposal as an attempt to kill the Civil Rights Act, which he opposed. Whatever reason, the act passed, as amended by Smith. However, the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, EEOC, didn't appear to be interested in ensuring equality on the basis of sex, leading in part to the 1966 establishment of the National Organization for Women. In 1972, the same year that the United States Congress passed Title Nine, which eliminated sex based discrimination in education for institutions receiving federal funding, and the United States Senate approved the Equal Rights Amendment, sending it to the states for ratification, the United Nations proclaimed that 1975 would be International Women's Year. The United States sent three representatives to the World Conference on Women, which was held in Mexico City from June 19 to July 2, 1975. The US representatives were Patricia Hutar, the former co chair of the Republican National Committee, and US Representative to the UN Commission on the Status of Women; Jewel Lafontant, former Deputy Solicitor General of the Department of Justice; and Jill Ruckelshaus, former head of the White House Office of Women's Programs. The United States did not sign on to the resulting world plan of action because it included anti Zionist language, but the conference did inspire action within the United States. In January, 1975, President Gerald Ford created the 35 member National Commission on the Observance of International Women's Year, with the goal of, "encouraging cooperative activity in the field of women's rights and responsibilities." A congressional statute extended the commission to March 31, 1978. When Jimmy Carter was inaugurated in January, 1977, he continued to support the commission and increased the membership, naming former US Representative Bella Abzug as the presiding member. Other members included poet Maya Angelou, former first lady Betty Ford, former US Representative Martha Griffiths. civil rights leader Coretta Scott King, actress Jean Stapleton, and journalist and co founder of the National Women's Political Caucus, Gloria Steinem. Congressional legislation approved $5 million for a national conference to investigate how federal legislation could best help women. From February to July, 1977, all 50 states and six territories held their own conventions, to elect delegates and to consider recommendations to bring to Houston. Around 130,000 people, mostly, though not exclusively women, participated in the local conventions. In September, 1977, Kathy Switzer, the first woman to officially run the Boston Marathon 10 years earlier, kicked off the first leg of a 2600 mile relay carrying a symbolic torch from Seneca Falls, New York, to Houston, Texas. The several 1000 relay runners each signed a Declaration of American Women, written by Maya Angelou, which ended, "We pledge ourselves with all the strength of our dedication to this struggle to form a more perfect union." 51 days after the torch departed Seneca Falls, it arrived in Houston where Latina college student, Sylvia Ortiz, Black high school student, Michelle Cearcy, and white physical education teacher Peggy Kokernot led a crowd through the final mile. The crowd included Betty Friedan, Bella Abzug and Billie Jean King. The conference opened on November 18, 1977, in the Sam Houston Coliseum, with several opening ceremony speakers, including members of the commission, along with First Ladies, Rosalyn Carter, Betty Ford, and Lady Bird Johnson. In her keynote address, Representative Barbara Jordan of Texas, the first Black woman from the south elected to Congress, reminded the participants, "5 million dollars from the United States Treasury was appropriated for this conference. If we now do nothing positive, constructive and healing, we will have wasted more than money. We will have negated an opportunity to make a difference. Not making a difference is a cost we cannot afford. The cause of equal and human rights for women will reap what is sown in Houston, Texas, November 18 through 21, 1977."

Over the four days of the conference, delegates debated and voted on 26 resolutions on women's rights as part of a national plan of action, resulting in a final publication titled, "The Spirit of Houston: the First National Women's Conference. An Official Report to the President, the Congress, and the People of the United States." The National Women's Conference was not alone in Houston that weekend, as some 15,000 people gathered in the Astrodome under the leadership of conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, who was spearheading a growing movement for traditional so-called "pro family values" and against the Equal Rights Amendment. At the time of the competing conferences, the Equal Rights Amendment had been ratified by 35 of the necessary 38 states. Despite an extension from the original deadline to 1982, the efforts of Schlafly and her campaign were successful in blocking any further state ratifications. It wasn't until 2017 that Nevada became the 36th state to ratify, followed by Illinois in 2018, and Virginia in 2020. As of right now, the status of the ERA remains in legal limbo. Joining me now, to help us learn about the National Women's Conference are Dr. Nancy Beck Young, the Moores Professor of History, and Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell, Assistant Professor of Digital Media, who are both on the leadership team for the "Sharing Stories from 1977" project through the Center for Public History at the University of Houston.

Hi, Nancy. Hi, Liz, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 10:59

Thank you for having us.

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 11:01

Yes. Looking forward to it. And thank you.

Kelly Therese Pollock 11:03

Yeah. So I want to start by asking both of you how you got involved in this project, and maybe even how you first heard about the National Women's Conference? Maybe you already knew about it, but it was new to me, which was kind of shocking. So, Nancy, do you want to start talking a little bit about how you got involved in this project?

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 11:23

Sure. So let me answer your second question first, and your first question second. I think that that adds a bit of chronology to all of this. So I've been a professor at the University of Houston now for 15 years, and I was hired to a senior position here. And so part of what I did when getting ready to come down here was think a lot about dissertation topics and thesis topics that I could point students toward, and that could be researched, at least in part in the Houston area. And I had known that there was this thing, the National Women's Conference, but I hadn't really dug deeply into it. And it was one of the topics that was on my list of talking points for my job interview as something that I might point a future, a future student toward, but I never really did anything more than that with it. Until if you fast forward, maybe five-ish years later, I was chair of the department. I'm again chair of the department. That's my problem, literally. And in my first iteration of being department chair, we had a search for a US women's historian, and Leandra Zarnow was one of our candidates, one of our finalist candidates for the position. And I always do the last interview with candidates when I'm chair so that I can answer any questions that they have, and just talk to them about teaching here and researching here. And because there's quite a bit of overlap between Leandra's interests and mine, we probably took longer with that conversation than maybe some other conversations. And she started talking about her fascination with the National Women's Conference. And so pretty quickly after she was hired, we started talking about ways that we could collaborate on this. I had a new interest in digital humanities. And we started by applying for and getting an NEH grant to run a summer seminar, which we did in the summer of 2017, for college teachers. And later that year, we organized and hosted a two or three day conference that drew hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people from all around the country and some international scholars as well, to Houston for a symposium that featured former participants at the National Women's Conference as speakers, as well as academics who are studying the National Women's Conference. It was a great good time. And then from there, we started talking about what do we do next with this? And what might that next look like? And one thing that had been suggested that we had thought about was an edited collection out of the conference, you know, picking the six or eight best papers and doing an edited collection, but that felt flat, and like it wouldn't really move the scholarly needle, as it were. And so we shifted pretty quickly to envisioning what a digital humanities project might look like. And so we taught the concept in multiple courses, a grad seminar that we taught together, and then in a variety of undergraduate courses, and we started figuring out what we wanted a digital humanities project to look like: a merger of biographical essays and oral histories, about and with former participants, combined with building a demographic database about all of the former participants. So those were our basic ideas. We applied for and got a second NEH grant, this one an NEH collaborative grant, and it was in the planning stage for that that we first started talking to Liz and some other technologists on campus. And they joined our team that we have lovingly referred to as the "Boss Ladies Club." And someone actually called me a boss lady, either yesterday or today, and I said, "Well, you do know I'm in a chat group called "The Boss Ladies Club." So I didn't say any more because you have to have special entree to be included.

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 16:44

Yeah, and I hadn't been at UH particularly long, I joined the University in 2019. And it wasn't that long before I realized that the work I was doing, I'm an anthropologist, by training, but I do a lot of, my work is in media and technology. And I was really interested in human computer action. So I was there for probably only one semester before one of my colleagues mentioned this project to me, and I had never heard of the National Women's Conference. I was like, "Is this something that's held every year? Can I go? This sounds amazing." So, you know, looking into it, I was like, "How is this something that we don't all know about? This is a phenomenal event, it is extremely important to women's history. And if I can do anything to help make this material more accessible to people, because like if I mean, if I don't know it, I care quite a bit about the subject matter, then, I mean, who does know?" So being part of this project has meant, even on my side, getting to really run our presentation, our organization materials our content by original participants. And getting to talk to all these these participants is pretty much always moving to me, including, you know, a recent event we had where there were just there were women there who I had only seen in the promotional materials for this event. It was it was just like seeing them now, in the present, having only seen these photos of their original membership in that event, I just I couldn't stop kind of gawking. It was really, it was really cool. But I mean, also, I think it's important that this event was held in Texas, because we don't give ourselves very much credit for women's rights issues in Texas. We tend to get bogged down in the reputation that Texas has nationally, I think, and forget that we've actually had really good moments like this, where people from all over the country came and were here, and were fighting the good fight. And it was a lot of really people who are really beloved in women's history. And so yeah, getting to be involved in this project has been been a real honor.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:00

So I want to pick up on something you said, Liz, which is why don't we know about it? So I you know, I'm in the same position, right? I thought I knew everything about women's history in the United States. And I think I just forgot the 70s existed. I was born in 78. So it's all like right before I was born in it, you know, not history, but not the present. So do we have theories on why this isn't better known? And I think there's a Gloria Steinem quote where she says like, it's the most important thing in women's history that nobody knows about. So why why is that why, despite all this press it had at the time, don't more people know about this event?

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 19:38

I think that there are multiple reasons why we don't know. And they have a lot to do with the larger political context in which the National Women's Conference happened, and then the political context of after the Women's Conference, right. So the National Women's Conference comes in the late 1970s, when feminists think that they're this close to the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, which would have been such a huge victory, and the culmination of the struggles of the 1960s and the 1970s. And in fact, you can see in looking at the documentary record about the National Women's Conference, how the ERA was this through line through the conference. There were certainly plenty of other issues that participants discussed. And certainly for some, the ERA was not even in their top two or three or four issues. But for the conference overall, you can't talk about it without talking about the ERA, and the failure of the ERA just a few years later, to be ratified, I think plays a role in the forgetting of the conference. I think there are some other factors that play a role in the forgetting of the conference. And that is the triumph of Ronald Reagan's brand of conservatism in the 1980s, and the various sorts of things that you see in the literature about women and what women should be, and how women should exist and present in in society. It was somewhere in that 80s, 90s timeframe that the sociology researchers came out and talked about the chances of unmarried women in their 30s ever being married and having a family and all of this anti feminist thought that wove its way into the politics and popular culture of the time period. And the focus on the worship and adoration of the cult of Ronald Reagan, if I may say, is, is is is crucial here to all of this. So the short answer is if you mix together the failure of one of the signature items of the conference to be ratified, with the rise of the macho conservative politics of Reagan, and then with the very subtle, anti feminist ways that marriage gets brought back out, as you know, this, this thing that women must do. And if you're unmarried by the time you're in your 30s, then woe be unto you. I think all of this plays a role in moving the needle away from the conversations that women were having in the 1970s. And so much so that when issues that were contained within the 26 planks for the conference, see positive legislative action, it's not even linked necessarily to the National Women's Conference. I'm thinking about the Violence Against Women Act, because one of the planks dealt with abuse, physical abuse against women, by by romantic partners, be they spouses or or not. And the Violence Against Women Act was was a major accomplishment. But I can't think of a single commentator who linked that with the NWC. But I don't think you get to the Violence Against Women Act without the National Women's Conference, and feminists more generally, in the 60s and 70s, talking about this as a very real social problem that needed attention.

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 24:20

That would have been my guess, too, as a fellow 1978 baby. I would say like, it just it feels like the 80s was such a period of backlash, that a kind of erasure happened, and a lot of the folks that we've seen who were involved in the original events who have participated in events celebrating the development of this project, a lot of them have been sitting on these incredibly cool materials. They've just been sitting on all these artifacts like you know, shirts from the original events, flyers, programs, buttons, and it seems like nobody's asked for them until this project. And I mean, there's there's this legacy that's lurking in our country, though. I remember one of the participants telling me, there's a woman who was pregnant, who was featured in a lot of the photos. And she said, you know, she had a baby right afterwards that she named the baby ERA, Era after the Equal Rights Amendment. So she was she was like, "You should know that." And yeah, when I do when I do kind of evaluations, usability testing on our site with with people, we usually spend a big chunk of time talking about, you know, who's in the photographs, what was happening there, what it was, like, why it was life changing. And all of these things, I think, go into some of the histories that have been collected, as well. I'm lucky that people spend the time to talk to me about that stuff, while we're, while we're going through things like does the search work effectively.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:55

So maybe we could talk some about who was at this conference, and there were a lot of mostly women at this conference. Who were they? Where did they come from? How did they get to Houston, you know, to be a part of this conference? Because I think that's so important in understanding the story of that weekend.

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 26:15

Well, I think to answer that question, we have to go back and talk about how the conference was created. So the conference was the product of federal legislation. Congress actually passed a law. Now we could end the sentence there, right, Congress actually passed a law. And that might be news in and of itself. But Congress passed a law to fund this conference to study what women wanted with regard to federal policy. This was the first time that the federal government had done something like that, that a conference like this had ever happened. Nothing like that has happened since. And I won't hold my breath for any such legislation to be passed in the next two years, at least. So they passed the law. And in passing the law, there were requirements built in about what the delegates should look like. So there was a requirement number one, that the delegates represent the racial and ethnic diversity of the United States, and every registration form, and I've literally touched every registration form for every delegate. Every registration form had a questionnaire that spoke the language of race and ethnicity of the 1970s that had the following checkboxes: Are you white? Are you Black? Are you Hispanic? Are you Asian American? Are you Native American? Are you other? So five categories, plus the dreaded "other" there to try to have a racial and ethnic diversity at the conference. And the result was amazingly, overwhelmingly diverse, more diverse, obviously, than Congress was then. But even more diverse than Congress is now, Congress is still pretty white. So that was one piece of diversity that the federal legislation called for that was achieved. Another piece of diversity was required in the legislation, and that was income bracket diversity. And, again, the conference delegates who came together, more diverse on that score than is true for Congress, but maybe not as diverse as the organizers had hoped for, just because of the difficulty for a person whose primary focus is to make sure they earn enough money to make rent and pay for the fill in the blank, diabetes medicine, high blood pressure medicine, kids' college, orthodontia, whatever, may make it difficult to attend, even with scholarship assistance, and there was scholarship assistance for lower income participants, but a tremendous amount of diversity. The only type of diversity that wasn't really there was gender diversity, because the overwhelming percentage of participants were in fact, women. There were a few men who were elected, but that tended to happen from very conservative states that wanted to send very conservative delegations. So Mississippi sent husband and wife pairs, and one of the Mississippi delegates was married to the head honcho of the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi, so, you know, kind of kind of frightening stuff there. People listening won't see Liz covering her face in horror.

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 30:10

I definitely facepalmed there.

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 30:13

Yes, yes, yes. So that's a sense of who they were, people from all walks of life. And I'll say that, that has been inspirational and challenging in how we've taught this project in classes. So all of those biographies for the 1800 or so, participants in the conference are all being written by students, some undergraduate, more undergraduate than graduate, some graduate students, but mostly undergraduate students. And so if you get someone like, oh, I don't know, Maxine Waters, who's a member of Congress from California, and most people who follow politics, are familiar with Maxine Waters and would know who she is. Or if you got Ann Richards, who was a former governor of Texas, and a pretty outspoken feminist, and the like, you know, you're gonna be overwhelmed with sources, and you're gonna find a lot. But what if you get someone who lived a life hidden from history? What if you get someone who was working class in background? They're not going to have their name in the paper, just a whole bunch, because they're not members of 57 different civic organizations, and they're not lobbying the state legislature to pass X,Y, and Z bills, and they're not running for Congress themselves. They're working in a factory or wherever, trying to make rent. And so it was that wonderful mix. And the thing that we tell students is that all participants had equal value in making the National Women's Conference what it was. We can't single out the well known names like Maxine Waters, like Ann Richards, like Barbara Jordan, like Gloria Steinem, and say that they are the totality of the conference. The average folk whose names are lost to history make a huge difference, as well. And we're hoping that our project, recovers them, and rescues them and puts them in the prominent position they deserve.

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 32:38

I think it's been really powerful for our students, not only to see the ripples of the people who were involved in this originally who have gone on to remain politically active. For example, Sylvia Garcia, who is congresswoman from East Houston was involved. And, you know, it's, it's been really cool to see these, these folks who are still, that are active at the national level, who attended in their 20s in there, you know, and had these formative experiences there, like, like Sylvia Garcia. But the other thing that's been really poignant for, for my students, I think, too has been to see the involvement of the University of Houston in this event, and to just be able to use our maps to locate specific places they know, and to identify them as this, this really important part of women's history. It connects it to their own experiences in the present. And you know, to the folks who I've worked with, it makes them feel like they have a contribution to make, you know, being here, in Houston, in Texas, this place has played a role, this university has played a role, and it can continue to play a role. And my challenge being on the tech side of things, also is to all these different stories that Nancy's mentioning, to help people to be able to find them, again, is part of is one of the usability challenges, really, because search is a complicated thing. We have so much material, and trying to figure out how to classify it and organize it in 2023 is really, you know, it breaks your mind a little bit trying to figure out how are we going to adapt the way it was classified then into now and make it easy to find the people who not just people, I guess, that we're looking for not just if we search on Gloria Steinem, for example. But if we're searching for, you know, all the people from a particular part of the country or we're searching for people from particular socio economic backgrounds, making sure those people come up and are honored as part of the project. So I think about the tech side a lot, but it's really, it's really the human side of the tech side of this are absolutely connected.

Kelly Therese Pollock 34:54

So you mentioned that there were 26 planks that they were voting on looking at in the conference. So obviously, we're not going to list all of them. But I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the kinds of things if they're looking for: what do women want out of legislation? What were the kinds of things that women at this conference wanted?

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 35:11

Sure. And so the planks are much more encompassing than listeners might imagine at first thought. Yes, there are the expected subjects, the ERA being one, reproductive freedom being another, sexual preference being another. So those are expected things. The issue of violence against women, with a more old fashioned language being battered women being built the language from the 1970s, not unexpected that that would be there. There was a plank, on on credit. And we might not think that one so much today, because it's relatively easy to get credit today. It's not so easy, maybe to have good credit today. But if you go back to the 1970s, I'll tell you a story from just a little bit earlier in the 1970s. Pat Schroeder was elected to Congress from Colorado. And so that meant a lot of airplane trips from Denver to DC and DC to Denver. She did not, prior to her election to Congress, have a credit card in her own name. And American Express would not give her a credit card in her own name, but would only give her one in her husband's name with a very tiny credit limit that would buy about a third of what a ticket would cost. And so she used to joke, "What am I supposed to do, parachute out of the plane over St. Louis?" because that was about all that her credit would would require. Another congressional story bringing in another woman in Congress again, a little bit earlier than this time period. Lindy Boggs was a democratic woman in Congress from Louisiana. And she was a member of what was then called the House Banking and Currency Committee. It's now the Financial Services Committee. And so they were considering some equal credit legislation that really had more of its focus dealing with racial discrimination in in credit, and Lindy Boggs in her best New Orleans, more deep south of southern drawl, not the twangy nasally thing that I've got going on, said, "Now gentleman, I'm sure you had forgotten to omit women from the bill." And in that very bless your heart kind of way that only a proper southern lady can pull off, pulled off writing women into this equal credit legislation in the very, very early 1970s. It was very difficult for women to establish credit records on their own because of the assumption that we lived in one income households were men worked, and women tended to children at home. And of course, that model was never quite as true as the myth would have it be and was busting apart at every imaginable seam and then some in the 1970s. So access to credit was a huge, huge problem that so many of the participants talk about when you start reading oral histories with women who were delegates to the National Women's Conference. Some of them even tried to form women only credit unions and the like to, you know, bust up the patriarchy. So we have things like that. There were also planks that were dealing with the arts and humanities. There was a plank that dealt with rural women. There was a plank that dealt with older women, so as diverse as you can possibly imagine. The planks really did show the thoughtfulness and the breadth and depth of representation and I almost forgot another really significant and controversial to negotiate plank, and that was the minority women plank. So, there's another important piece about the NWC is the way that it blows up the myth of feminism being for middle class and upper middle class elite white women. And there's quite a bit of pushback, both by lesbians who are pushing hard for the sexual preference plank that were bullied, if you can believe it, there were feminists who were opposed to including lesbians within the feminist movement. I know, it's totally crazy to hear that in 2023. But it's true. And one of the loudest opponents of providing space for lesbians in the feminist movement was none other than Betty Friedan. And more than a few delegates gave Friedan a talking to at the conference. And she ultimately agreed to go on the floor and speak in favor of the sexual preference plank. But there was a lot of politicking going on over that issue, and over the issue of minority women, and writing a plank that was inclusive, and honoring women of color.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:23

I definitely want to talk some about how listeners can get involved, how could they can learn more on the sites, how they can contribute, if they have their own memories, and memorabilia and stuff. So Liz, I wonder if you could talk some about the site and the way it's organized and how people can learn more on it.

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 41:41

Yeah, so as I mentioned, we have a fairly complex situation going on. We've got, we've got so much powerful data to present. And so the site is a combination of resources grouped according to kind of wherever they happened, so people can locate and really map out the experience of the events in space and time. And then we also have the capacity to search, you know, in degrees of complexity for specific individuals involved, we can you can browse through the the materials that we've collected. You can I mean, you can even learn about all of us the project team, but there is a resource, a part of this site that allows you to contribute, to get involved. And this can really take the form even for people who are just interested in helping to test out the site. You know, we're hoping to appeal to a really broad audience. So when we talked about like, "Who is this for?" I mean, you know, the pithy answer is, "everybody," but at the same time, we had to define, really a range of kind of target audiences. So apart from, you know, the original participants in the event, we also want this to be a resource that can be accessed by, you know, people who are looking into this for a school project, you know, before even the university level. So we are always looking for people to help test the site. Tests are often run by students. As Nancy said, we really try to involve students at absolutely every level on this. So the students who I've trained on my side will, basically whenever we develop and set up a new aspect of the site, so a new, you know, a new search element, a new capacity to find things on our interactive map, we will have people try it out to see if it's actually effective. And this is really good feedback for our designers who are also usually students as well. Not usually. They are our students, as well. So really, folks can, can go to the site, and which SharingStories1977.uh.edu. And there's a kind of prompt in there to contribute, if you do have materials. We kind of foreground the "how to contribute" section. And so you know, we'd absolutely love to hear from people, if you have any materials that could be useful. But even if you just think it's cool and want to get involved in some way, we have a possible role for everybody. I love testing with original participants, but I actually also really love testing with college students and high school students. They are they're great because they're it's not that, you know, there's this sense that like Gen Z, they're they're so tech savvy. It's actually that their standards are rather high for what's engaging. So it's the subject matter actually to them is almost less important than the experience. If the experience is good, if the experience is intuitive, smooth, easy to navigate, then they'll get into it. So like testing with high schoolers who are like, "National Womwn's Conference? What is that?" And seeing them kind of go, "Oh, this is this is really cool," is is one of the highlights of doing testing with with people in general. I like the the teenage audiences. They'll they'll tell you straight if you're not engaging them.

Kelly Therese Pollock 45:20

Can I send you a middle schooler?

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 45:22

Yes. I love middle schoolers too. Yeah. Similarly, like, again, if they're not engaged, you'll know. And they're a great, they're a great test case. Like a you know, middle aged folks are more diplomatic. Middle schoolers and high schoolers will tell it to you.

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 45:41

Can I add another way that people out there in podcast land can get involved? So we really do want you to participate as testers, that's really super, super important. But if you are a college teacher, or a high school teacher listening to us, and you want to involve the project with your students, please reach out. If you think having your students write biographies would be a fascinating and creative assignment that would engage them, please reach out. We would love to have you become a part of our crowdsource team. So reach out. And we would be more than happy to meet with you to explain what the biography assignments are like, or maybe what the oral history assignments are like. Maybe you would like to involve your students in having an intergenerational conversation with someone who was a participant in Houston in 1977. So that would be another way for people listening to get involved.

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:45

I love it. And I will put links in show notes so that people can find things that way as well. And for anyone who's a chronological thinker like I am, there's a lovely timeline. That's wonderful. I love the timeline. And there's links to videos for things that there are videos of including, we're not going to discuss Phyllis Schlafly here. But if you want to go watch Phyllis Schlafly, she's in the timeline. So you can find her. Is there anything else that either of you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 47:17

Oh, boy. I think we need to bring the National Women's Conference back. I feel like yes, I just, how was this? How is this just not something we're constantly doing? I mean, especially at this point in American political history, why are we not getting together? And getting mad? And you know, getting political? And, yeah, I think like, this is this is one step, making sure people understand that this happened, I think is the first step to making it maybe making it happen.

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 47:51

Yeah, yeah. Well, I think that there are people getting together and getting mad. But I think it's the wrong people getting together and getting mad, and engaging in the wrong kind of behavior with their anger. I think it is important to stress that this was an entirely peaceful and thoughtful and cerebral exchange of ideas. And I think that that would be the way to engage discontent with the status quo. And a status quo that is worsening, right?

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 48:30

Yeah,yeah. I mean, there were counter protesters for this for the original events. And it still, it still happened. It was still powerful. There was certainly like, you know, a robust set of forces who were organizing against this event. We won't get, we won't mention anybody's name. But you know, there was pushback then, and...

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 48:54

And there were conservative voices within the National Women's Conference. Not every delegate agreed that the ERA was a good idea, or women should have access to safe and legal reproductive care as part of their health care. There were vociferous opponents to both of those, both of those issues.

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 49:18

Yeah, that's one of the coolest things about it, for me is is the diversity, that it wasn't just, you know, a symposium of the privileged. So that's the kind of thing I would love to see come back, is really all of us talking to each other, you know, across backgrounds, and yeah, across even political orientations.

Kelly Therese Pollock 49:37

All right, well, if you're listening to this podcast four years from now, when we hit the 50th anniversary, we're all going to Houston, whether anyone plans it or not. So...

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 49:45

Yes, you're welcome.

Kelly Therese Pollock 49:47

Nancy, Liz, thank you so much. This was really really fun to learn about and I'm so thrilled to hear about your project.

Dr. Nancy Beck Young 49:55

Thank you, Kelly. It was a great pleasure talking to you and much good luck with your podcasting.

Kelly Therese Pollock 50:02

Thank you.

Dr. Elizabeth Rodwell 50:02

Yeah, thank you so much for having us. It was super fun.

Teddy 50:29

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources use for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Nancy Beck Young

Nancy Beck Young is a historian of twentieth-century American politics. Her research questions how ideology has shaped public policy and political institutions. Much of her work involves study of Congress, the presidency, electoral politics, and first ladies. Dr. Young is also interested in Texas political history, especially Texans in Washington. She joined the faculty of the University of Houston in 2007 after teaching for ten years at McKendree College in Illinois. She has held fellowships at the Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University and at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Along with colleague Leandra Zarnow, she was awarded funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to host a 2017 Summer Seminar for College and University Teachers entitled Gender, the State, and the 1977 International Women’s Year Conference.

Elizabeth Rodwell

I am a media anthropologist who is interested in interactivity, television, emergent technology (in general), and artificial intelligence (specifically). I am also a usability researcher (UX). My first book Push the Button: Interactive Television and Collaborative Journalism in Japan (forthcoming) examines the post-Fukushima tensions in the Japanese journalism and television industries, and seeks to account for the ways that media professionals are responding to increasingly skeptical and distracted audiences. I also track the global debut of interactive television in Japan– a cutting-edge fusion of mediums that represented the most dramatic departure from existing television technology in several decades. I was interested in examining how the concept and practice of participation change as technology evolves the means by which people can contribute.

Currently I am working on a project at the intersection of artificial intelligence / machine learning and user experience (UX). Partnering with UX researchers and designers in companies both in the U.S. and Japan, and I am exploring what it means to think about usability when we’re attempting to replicate human interaction via machine.