Negro League Baseball

In its earliest years, the National League was not segregated, and a few teams included Black ballplayers, but in 1887 major and minor league owners adopted a so-called “gentlemen’s agreement” that no new contracts would be given to Black players. In 1920, pitcher and manager Rube Foster founded the first of the Negro Leagues, the Negro National League, to organize professional Black baseball, which was played at a very high level. Other professional Negro leagues followed, and for decades the stars of the game played in the Negro Leagues, until the National League and American League began to slowly accept Black players, starting with Jackie Robinson in 1947.

Joining me in this episode is Dr. Leslie Heaphy, Associate Professor of History at Kent State University at Stark, Vice President of the Society for American Baseball Research, founding editor of Black Ball, and author of The Negro Leagues, 1869-1960.

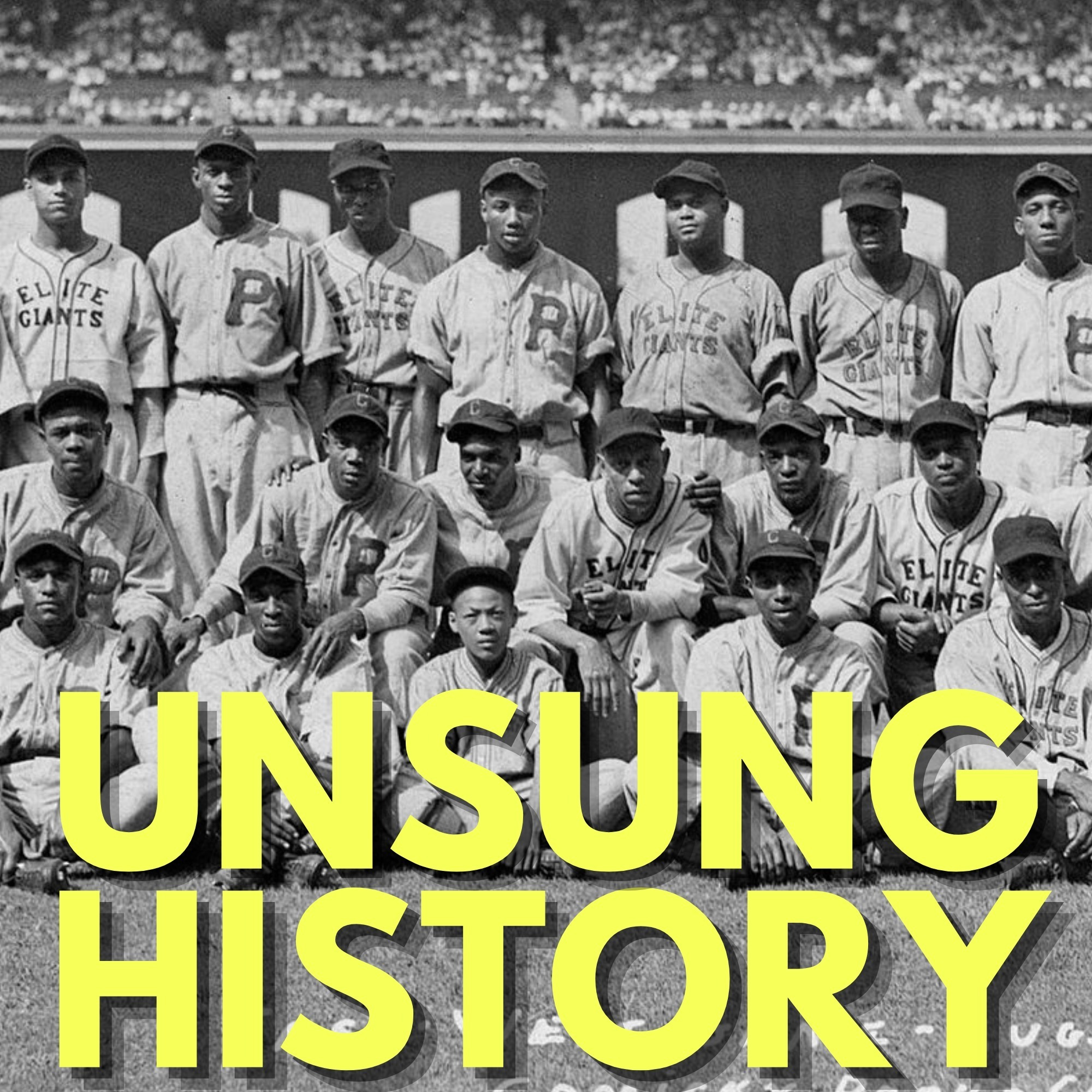

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “Boogaboo (Fox Trot),” composed by Jelly Roll Morton and performed by Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers Camden, New Jersey, on June 11, 1928; the music is in the public domain and available via Wikimedia Commons.The episode image is from the fourth Negro League East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park in Chicago on August 23, 1936; the photograph is in the public domain and available via Wikimedia Commons.

Additional Sources:

- “The History Of Baseball And Civil Rights In America,” National Baseball Hall of Fame.

- “Bud Fowler’s Life Blazed A Trail From Cooperstown,” by Isabelle Minasian, National Baseball Hall Of Fame.

- “6 Decades Before Jackie Robinson, This Man Broke Baseball’s Color Barrier: Moses Fleetwood Walker played for a Major League Baseball team in the 1880s,” by Farrell Evans, History.com, Originally published April 27, 2022, and updated January 22, 2024.

- “The Great Migration (1910-1970),” National Archives.

- “The League [video],” Magnolia Pictures.

- “A 20th Century Baseball Institution,” by Matt Kelly, MLB.com.

- “The Negro League revolutionized baseball – MLB's new rules are part of its legacy,” by Dave Davies, NPR Fresh Air, July 10, 2023.

- “The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball,” National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers, to listen too.

Americans have been playing baseball, or at least sports resembling what eventually became baseball, since before the American Revolution. In 1845, a bank clerk named Alexander Joy Cartwright, a member of the New York Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, codified the rules of the game, many of which, like the three strike rule, are still in place today. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known today as simply the National League, was founded on February 2, 1876, replacing the earlier National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, or NAPBBP. In the early years of the NL, the world's oldest extant professional team sports league, there were a few Black players on the teams, starting with Bud Fowler, a pitcher, catcher, and second baseman, who played in the minor leagues in 1878. On May 1, 1884, Moses Fleetwood Walker debuted in the major leagues with the Toledo Blue Stockings, but he faced rampant racism, including the threat of a lynch mob if he traveled with the team to Virginia. Even his teammate, pitcher Tony Mullane said, "He was the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro, and whenever I had to pitch to him, I used anything I wanted without looking at his signals." Within a few years, even those few Black players would be forced out, with the so called gentleman's agreement, that major and minor league owners adopted in 1887, that no new contracts would be given to Black players. By the turn of the century, the National League was a whites only league. There were, of course, many Black baseball teams, some of them quite good. One of the stars of Black baseball was pitcher Andrew "Rube" Foster, who won 44 games in a row for the Philadelphia Cuban X Giants. In 1902. In 1911, Foster founded the Chicago American Giants team, and arranged for the team to play in Southside Park, at 39th and Wentworth, which the Chicago White Sox had just left for the newly built nearby Comiskey Park. However, without an organized league, it was challenging to set schedules, and white booking agents kept much of the proceeds. As Foster said at the time, "The wild reckless scramble under the guise of baseball is keeping us down, and we will always be the underdog until we can successfully employ the methods that have brought success to the great powers that be in baseball of the present era. Organization." Foster's vision of that organization finally came to fruition when the owners of several Black baseball teams came together at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City on February 13, 1920, forming the Negro National League with the slogan, "We are the ship, all else the sea." As president of the league, Foster controlled the team schedules and took a 5% cut of all gate receipts. In addition to the Chicago American Giants, seven other teams initially joined the league: the Chicago Giants, Cuban Stars, Dayton Marcos, Detroit Stars, Indianapolis ABCs, Kansas City Monarchs and St. Louis Giants, mostly located in cities whose Black populations had exploded during the Great Migration, as Black people moved from the south to the north and midwest in search of employment, and escape from some of the worst of racial violence. Foster's plan worked, and at least some of the teams found early financial success. The Chicago American Giants, for instance, drew 200,000 fans during their 1921 season. The success of the Negro National League inspired other leagues to form. In 1923, two teams that had been associate members of the NNL, meaning that they played an NNL teams but didn't compete for the championship, formed their own league, the Eastern Colored League, whose charter members were the Hilldale Club from near Philadelphia, the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, the Brooklyn Royal Giants, the Cuban Stars (East), the New York Lincoln Giants, and the Baltimore Black Sox. The leagues stole players from one another. They also held a World Series from 1924 to 1927. In 1929, J. L. Wilkinson, the owner of the Kansas City Monarchs, commissioned an Omaha company to build him portable generator light towers, 50 feet tall. He had to mortgage everything he owned to do so, but on April 28, 1930, the Monarchs played their first night game, five years before any white major league team played a night game, allowing fans to attend games after work. It was wildly popular. But the Negro League suffered with the onset of the Great Depression, and the National Negro League folded in 1931. Two years later, Black businessman Gus Greenlee of Pittsburgh, founded the second Negro National League with eight teams: the Pittsburgh Crawfords, the Chicago American Giants, the Homestead Grays, the Nashville Elite Giants, the Baltimore Sox, the Columbus Bluebirds, the Indianapolis ABCs and the Akron Grays, although the Columbus team folded halfway through the season. Greenlee's great innovation was the East West game, a popular All Star game played at Chicago's Comiskey Park each year, where fans chose the starting lineups via newspaper balloting. In 1937, the Negro American League founded in the west, with nine founding teams: the Kansas City Monarchs, the Cincinnati Tigers, the Chicago American Giants, the Indianapolis Athletics, the Birmingham Black Barons, the Detroit Stars, the Memphis Red Sox, and the St. Louis Stars. In 1942, the two leagues agreed to restart the World Series. The Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League swept the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League in four straight games for the championship that year. In late 1945, Branch Rickey, the club president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, signed Jackie Robinson, formerly of the Kansas City Monarchs to the Dodgers organization. After a season on the class AAA Montreal Royals, the Dodgers called Robinson up to the major leagues in the 1947 season, finally breaking the long standing color barrier. As Black baseball players headed to the major leagues, so did Black fans. The Negro National League folded after the 1948 season, which ended the Negro World Series. The Negro American League continued playing even with dwindling crowds. The final East West All Star game was played on August 27, 1962, in Kansas City. The Negro American League folded at the end of the 1962 season. Joining me now to help us understand what life was like for players in the Negro Leagues is Dr. Leslie Heaphy, Associate Professor of History at Kent State University at Stark, Vice President of the Society for American Baseball Research, founding editor of "Black Ball," and the author of "The Negro Leagues, 1869 to 1960."

Leslie, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 11:11

Thank you, Kelly. I appreciate the opportunity to come and chat. It's always fun.

Kelly 11:15

Yeah. So I want to hear a little bit about how you first got into baseball history and thinking about and studying the Negro League specifically.

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 11:24

So I've been a baseball fan since I was a little kid, for as long as long as I can remember, mostly because my dad was a huge baseball fan. He played baseball in college and things like that. So, and growing up in New York, you had the opportunity to listen to two teams on the radio then. So we listen to the Yankees and the Mets. And of course, I'm a Mets fan, still am. And in Ohio, they accept that because I'm not a Yankee fan. So it's okay. My dad, of course, was Yankees fan. And everybody always asks, "Well, then how did you end up as Mets fan?" and I said, "Well, even as a little kid, I remember thinking that George Steinbrenner was not a nice man. And therefore I couldn't like he was just mean, I thought as a little kid. So I was like, I don't like him." And some of them may have been, well, my brother, they all liked the Yankees. So I had to do something different. I don't know. But I like the Mets. So I've always liked baseball. And I've always liked history. And I was, you know, read baseball, watched baseball. And when I was in college, it was really in grad school, when I, I was actually looking for a topic for one of my very first seminar courses. And I didn't know what I was gonna do. And I was literally in the library one day, and I was sort of walking up and down the shelves trying to find thinking, what wouldn't be so bad. It was a labor history class, actually, that I had to find a project for. And I was like, "What wouldn't be so bad?" And I was in the section of the library, the University of Toledo was one of the depositories for lots of federal records related to the Department of Labor. So I thought, well, child labor might be kind of interesting. And so that's literally what I was standing there thinking, when one of my fellow grad students came up and asked me what I was doing. And I told him and I said, "Hey, this might not be too bad." And he goes, "Well, what would you want to do?" And I said, "Well, something with baseball, but they'll never let me," and he said, "Why not?" And that was literally all it took. And I went, I was like, Oh, I don't know, I just assume, because I started a long time ago. And that kind of thing. I just didn't know anybody. I didn't know you could even do that. And so I went asked my professor, and he said, "Well sure, there's labor in baseball, why not?" And I said, "Well, I think I want to do something on the Negro Leagues." And he said, "Well, what's that?" And I said, "Well, it's the stories of African Americans that nobody knows anything about. And I've said, I can't find anything much. And so I'm curious as to how that all worked." And I really didn't know. And as they say, the rest is history. Literally, and I told my students all the time, it's sometimes just how simple it can be to not ignore something. He literally said to me, "Why not?" And I was like, "Well, I don't know. I just assumed I couldn't." And I went and asked. And if I hadn't, I would be doing something very, very different today, I think.

Kelly 14:00

So let's talk then a little bit about what we know and don't know about the Negro League. So this isn't like Major League Baseball today, where you know, the second a game is over, you could read like an entire narrative of what happened and and all the stats and everything. What, what kind of records do we still have access to, what isn't really knowable about the Negro League?

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 14:20

Sure. The Negro Leagues lasted from the official Negro Leagues, from 1920 to right around 1960, '61, '62. There's some, some people debate over that ending point. But somewhere, I usually say 1960, but so for about 40 years, but then there's the larger picture of Black baseball as a whole. So those are two very connected things. But I think, for a lot of people, what they think is that there are no records and that are that the stats are because stats are what everybody likes in baseball, right? That they're very incomplete. They can't be trusted at cetera, et cetera. And that's just not true. Maybe even 20 years ago, that was more true, but certainly not today. People would be very shocked, I think to realize that the work that people have done to put together records for Negro League play, official Negro League play, particularly between 1920 and 1948, which are really the heart of it, so a little over 25 years right, are pretty complete. On some of those years, they're at 95 to 96%, complete. And what most people don't know is Major League Baseball records are not complete. There are always changes being made to those, in some ways, this mirrors that in that sense, but it's taken a lot longer, obviously, to put them together. But the problem comes in, when people want to compare Negro League stats to Major League stats, and then what and then that's why they think," Well, when I only see on a statistical reference, you know, reference to 50, or 60, games that must be incomplete." And the answer is no, that's actually, that's actually, because there's a difference, because of who they were. What most people don't understand is that Negro League teams played officially, typically, somewhere around 60 games a year, 55-57, or somewhere in that, you know, and it varied. They didn't even all play the same number, because games got rained out, they didn't have to make them up, they didn't always have the resources to et cetera. So people will look at that and say,"Well, this team had a record that adds up to 55 games, and that one has a record that adds up to 60. So clearly, they're not complete," and you're like, "No, actually they are. The other 140 or so games that most Negro League teams played were exhibition and barnstorming games. And those are a whole separate entity, you know, that makes it much more difficult to collect, to figure out because they played everywhere and anywhere. So when those depending on the team, depending on the year, we might have 20% of the record, or we might have 80%. But that hasn't been where most of the work has been done. And so on the staff side of things, they're much more complete for major Negro Leagues, which are now considered the equivalent of the major leagues, are much more complete than people think. The problem comes in, when you try to look up many of these players, sort of beyond the playing field, in terms of who they were, what their life was, like. It's what they did after baseball, which is much easier on major league players. That's where there's lots and lots and lots and lots and lots of gaps. Because, you know, our primary resource most of the time, has been newspapers. And so newspapers don't often follow players when they're done. Part of it was Black newspapers follow these teams and Black newspapers have gradually, not completely disappeared, but there are certainly far fewer of them than there were back in the day. And so the idea that they're going to follow these players after they're done, and things like that is much more difficult to do. So that's part of the difficulty is trying to well beyond the 20 or 30, big names. Were there's so much work to be done there. But that's what makes it fascinating. Those stories are still out there to be found. And every time we find a new piece of the story, I always tell people, I think it's out there, we just haven't found it. Are we going to find absolutely everything? Of course not. You never can. But there's certainly lots out there too. And we're still finding it. Unfortunately, you know, as each year passes, we have far fewer actual players that we can talk to. And many of them, you know, people say, well, their families are around. Yeah. But in many cases, they never really talked, in some cases, you find out their families never even really knew. Because it's kids and things that weren't born when their dads were playing. And so they didn't even realize. And so unfortunately, they're not often not a great resource. In fact, they're often coming to us saying what can you tell us about our and so that makes it difficult as well. But that's what also makes it fascinating. Oh, and so in terms of what we know, that's kind of, and of course, the farther back you go, the harder it is to fill in. And so our 19th century information is even far slimmer than our 20th century information.

Kelly 19:03

You mentioned people who like baseball, like stats, and stats are great, but you know, what I care about is like the rest of the story. So can you talk a little bit about what life was like for these ballplayers when they're on the road? What's their life actually look like? How much money are they making? You know, what, what is that whole experience like?

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 19:21

Yeah, and I people are always surprised to find out, I agree with you. I'm not the big stats person. I don't do that much. There are other people that get to do that. I am much more interested in the stories. And so for Black ballplayers, and it varies, you know, across '20 to '48 timeframe, but in general, the things that you can say that were pretty similar for all of them was they lived in a segregated America. And right there, that is the first most important thing you have to think about in terms of their experience. Their experience is going to be colored every single day by that specific fact. And of course, it will be worse in certain places than others. But what that meant was, travel was difficult, finding places to sleep, finding places to eat, finding places to play, because a lot of times they weren't allowed into. But as a consequence, you know, most of their travel, for example was done in individual cars, they just pile into, or the rare teams that had a bus. But that also meant often, they would go and play a game in one city, and then as soon as the game was done, they're not staying. They're taking off, to go play somewhere else, which might mean they pull over on the side of the road to sleep, if they don't have place, or they're driving through the night, and they take turns having to stop at gas stations and restaurants, where if they're not sure, they don't know if they're gonna get going to be able to get served. And so some people may have heard of the Green Book, but that was a very valuable resource for lots of people traveling to know places they could go what where they were going to be accepted and things. But often, what you had to rely on, so think about this, that was, whoever was the lightest skin member of your team that could potentially pass or at least not raise too many questions. And often, they would be the one that would go pay for the gas, they would be the one that would go in and, or you'd find a place that would say, yeah, we'll feed you, but you have to come around to the back of the restaurant, we're not going to let you in, or they'd go to the grocery, you know, and grab things from marketplace and just eat on the road. Consequently, that meant and this is something people don't think about, they often had to wash their uniforms in, you know, the sink at the ballpark, and then hang them out the windows as they drove so they would dry depending on where they are, which is why sometimes, you know, you see a lot of the Negro League official games taking place, in big cities, on the weekends, things like that. So you travel during the week, and know that by Friday, Saturday, Sunday, you're gonna get to be in Chicago, or Pittsburgh, or Philadelphia, where there are going to be places for you to stay. And that's when you can catch up on your laundry, and you can do some things that you can't do the rest of the week. And so when you start to think about that kind of circumstance, it's amazing they played it all, and it's amazing they played as well as they did, because you're constantly have and then I mean, that's just the travel part of it thinking about, you know, where are we going to eat? Where are we going to sleep, how long is our day going to be, but then you're also constantly thinking about how you're going to be treated as well. And that was true in the ballpark, outside of the ballpark. So it was a in many ways, to some extreme a never ending challenge, right in terms, thinking about that. And then of course, pay wise, I mean, some of them will say, you know, it's obviously no, no players back then, white, Black, doesn't matter, got paid anything like what they get paid today, but Black ball players, when they were on a steady team, a team that actually could meet its paychecks, and things like that, was a decent paycheck. It was comparable to what often a general laborer might be making in a week, you know, white or Black. And so for many, this was a pretty decent paycheck. It could vary from, you know, most of the time it was, you know, they might get paid 50 bucks a week, or they might be being paid by the month at $200. And certainly, there were some that got more than that, Satchel Paige being a good example of that. And many who were certainly under that. But what they didn't get, you know, in addition to that usually was you don't get a daily allowance for your food, you don't get any of those, right, it's just, and many of them were sending that money home to for their families that were left. And of course, the other thing people don't realize is that they only played and had league play during a certain part of the year. And when that was done, unlike today's, right, you're not going to continue to pick up a paycheck. So you might get paid for six months out of the year. It's not going to carry you through. And so then the thought of having to think about what are we going to do. And so this was where many of them would end up playing, going out to the West Coast and playing in California where it was integrated, or many of them went south and played in Latin America for the winters, because that was a better paycheck even than here most of the time. But it allowed them to continue to receive a paycheck. And then others went to work during the offseason, but then had to find work that would be that seasonal for them. So it's not surprising particularly early on, and this is late 19th century, early 20th century, so many of the ballplayers worked as waiters at hotels, because that was a more seasonal kind of and it was easier to and then later on a lot of factory work, things like that. But that that was part of the reality. Because otherwise, they they and their families weren't going to survive, but not to and not to make it sound all this terrible struggle. They all everyone you talk to every player that I've ever interviewed every one that I've listened to being interviewed by somebody else, family member, they'll talk about the same way how much they just loved playing the game. And so it was worth it for the most part. And they also will acknowledge they got to travel, they got to see the country, they got to see some of the world. In some, I mean, there's groups that went over to Japan in the 1920s. So they got literally to see some of the, which they never would have gotten to do otherwise without the impetus of baseball, because there just wasn't opportunity for them to travel that way. And so for many of them, those things, were the big positive and made it all, you know, all worthwhile. And they will tell you that the quality of play was as high as it could be. And so they always thought they were playing the best and the highest level of baseball that you can find.

Kelly 25:37

So let's talk about that a little bit. What what do we know about sort of the the skill level of the players in these leagues? Of course, some of them ended up later making the jump to the major leagues. So you know, what, what do we know about they're the kind of thing they were doing?

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 25:52

Yeah, well, I think the first thing that people need to realize, because I often get asked this question, do they use the same equipment, the same rule? And the answer was, yes. And literally, sometimes buying it from the same companies that major league companies and things like that. The difference was they they didn't get a new ball, every single game and every single at bat, things like that, but but they were basically, you know, and they played in major league stadiums a lot. They played in minor league stadiums, but they also played in the high school stadium, and they played in the park and things. And so the quality of play varied dramatically, depending on where you were playing and who you were playing against. But there is no doubt and the statistics, what we do have absolutely prove it, that just like in the majors, and any team, yeah, you've got the 300 hitters, but you've also got the 200 hitter on the same team, right. And the quality level is exactly the same. It goes to this the simple thing to realize that your color, your your skin, didn't determine your skill set, right, or your love of baseball. Everybody wanted to play. And it was just the problem was, of course, that they weren't allowed to play together. But they did. And so there's another way we know, we know, you know, the skill level of those who played in the games. And you can look at, you know, Josh Gibson, the big home run hitter, and Satchel Paige, winning the game, and then striking out the players that he did. But they also played against major league, barnstorming teams. They played against white teams on a regular basis, and held their own and beat them the same, you know, way they beat one another. And so those aren't, those are the good measurements when people want to say, "Yeah, but what was the how do we know what the quality?" And I'm like, "Well, there are lots of ways to do that." And those who do statistics do it better than I do. But for me, it's it's just, well, let's look at who they played against. When they were playing white teams, if that's going to be your measurement of what and that I mean, that's the other part of it. Is that your only measurement of success? For most people it is right, the major league. And so they did they played in fact, Kennesaw Mountain Landis, the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for many of those years, basically issued a and there's debate whether it was official or unofficial, regarding, to me a ban is a ban, against major league teams, full major league teams like the Detroit Tigers, playing the Homestead Grays, because he didn't want them to get beat. You know, and so that says a lot for what you ended up having happening instead is, you might be Dizzy Dean All Star Team. So it'd be a couple players from the Tigers couple players from the Yankees, but it wasn't a full, right. And sometimes those teams were also filled with minor leaguers, things like that. But these are still people in the highest ranks and Black teams beat them regularly, lost to them, you know, and so the quality, and now that they're looking at some of the statistical evidence, it's very clear that in single season kinds of records, Negro League players in that time period, are going to find themselves as Major League Baseball starts to release these records, holding some of those records for single seasons and things. And I think that will amaze some people will probably surprise others and maybe and generate the usual that can't be so this player is better than that player kind of conversation that you get in baseball, but the quality of play is everything that you expect. It's it's high, it's high level. No doubt about it.

Kelly 29:15

You've mentioned Satchel Paige a couple of times. Could we talk a little bit about him? I mean, this is a generational challenge. Like can you can you please just talk talk some about this phenomenal player?

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 29:27

Yeah, so Satchel is usually the player that most people know if they know anything about the Negro League, the pitcher who came along and had a very long career in the Negro Leagues and then a career in the in the majors, but he was in his 40s by the time that opportunity came along. And so here's the here's something to think about with Satchel. When he is signed by the then Cleveland Indians, Guardians today, right, in his rookie season for Major League Baseball, 42 years old, he was six and one at 42. And so that right there tells you something about Satchel. Satchel basically spent most of his main part of his career with the Kansas City Monarchs. And JL Wilkinson, the owner of the Monarchs actually at one point, bought Satchel his own plane, so that he could be where he needed to be, because Satchel basically was often an itinerant pitcher for the league. But when Satchel actually crashed the plane, JL Wilkinson banned him from flying it himself ever again, made his son be his pilot, because Satchel was so valuable that he didn't want anything to happen to him. Basically, you talk to people and you read accounts and things and they would constantly say the general idea was, if you could put Satchel on your placard, to announce, or your poster to announce your game, or by word of mouth, you guaranteed an increase in your attendance, because people were going to come see Satchel pitch. And so as consequence Paige, probably pitched for and against every every existing Negro League team, because they basically, and not really, but that's the best word I can think of to use, rented them out to vary. And so he'd go pitch, you know, three innings for this team. And then he'd leave, to go pitch three innings for in another game. And so he was the true itinerant. And so in some ways, it's sometimes hard then to put together all of Satchel's innings and things. And his won loss record as a consequence, might not be what people expect, because he wasn't pitching full games in one game. He was pitching full games in one day, but not necessarily. You know, and I think that right there tells you what kind of a player Satchel was. But he was also a character. And I think that's what has made him sort of this larger than life, kind of like Babe Ruth. He in terms of he loved the press, the press loved him and Satchel loved to talk to people. He loved to tell stories. And so today, a lot of the time is spent when you're hearing stories about Satchel going, "Is that really true, or was that Satchel exaggerating?" And Satchel being Satchel? Right? Did he have pinpoint control? Yes. Could he throw it over a bubblegum wrapper? Claim was yes, people have seen it. That's probably true. The story famous story about Cool Papa Bell being able to jump into bed after the light switch went off before the lights went out. Not technically true, an example of one of Satchel's kinds of stories. Now he named all his pitches, just because he could because he thought it was funny. And he liked to tell people that I could tell them what I was throwing and they even knowing they but yeah, when you call it a fastball, they know what's coming. But when you call the the Uncle Tom, they don't know what you're gonna throw until they learn. You know, so the stories about Satchel are as legendary as he is. But I mean, he really epitomizes what the Negro Leagues were all about, and certainly no one, no one will argue the talent level that Satchel had. So if you're thinking about a league that leagues that lasted for 40 years that had hundreds of players, they're, Satchel is not the only good player. And so to your earlier question, right? He's a good example of, yeah, he's the tip of the iceberg. But there were many just like him.

Kelly 33:10

So there were also some women who played in the Negro Leagues. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 33:16

Sure. So officially, when we think about the Negro Leagues, on official Negro League teams, there are three that actually played in what we would consider official Negro League games. And I say that because there are others who played on the on Black teams and things like that. And they all played in the in the 1950s. So 1953 in 1954. So Toni Stone, Connie Morgan and Mamie Johnson were the three and Toni Stone was the first one. And she came up with the Kansas City Monarchs in '53, was signed by them, plays the infield for the second base for the most part, and then she'll get traded from Indianapolis to Kansas City. And so when she gets traded, Connie and Mamie come in to to the Indianapolis Clowns in 1954. Connie was a infielder a little bit of outfield, and Mamie of course, was a pitcher, which made her pretty unique and makes her actually on that, on that level of major league play the first female professional pitcher we ever have. And her nickname was Peanut, because she stood about. I think she was exaggerating if you said she was five foot two, but all three of them were incredible athletes. All had played baseball, long before they ended up in the Negro Leagues, Toni probably more so than any of the others. Toni grew up in the St. Paul- Minneapolis area, played baseball there, played baseball in San Francisco, played baseball in New Orleans and then ended up with Kansas City and Indianapolis, and in fact question though, "Well how good were they? There's, these are just women." Well Toni made the all star team so you know, yes, popularity vote to some degree, but you're not going to vote in a player who's hitting 110. You're just not no matter how popular they are, and then Mamie, record of three and one in her first season. And Connie was a, probably athletically, one might maybe be able to argue, might have been the best, just just general all around athlete. She was from Philadelphia. And she was known in the Philadelphia area actually more for her basketball play than her baseball play, because she played on a number of basketball teams. And probably the most famous one was a team called the Honey Drippers. And she was one of their stars. But she also played on their baseball team. And so that brought her into the fold. And they're playing of course, '53 and '54, after Jackie Robinson has integrated reintegrated, Major League Baseball, and so some people, certainly, rightly can argue. Was this done partly to bring publicity? Sure, absolutely. But it's not going to work if they're not any good. And you won't keep them for full seasons. And if Toni hadn't been any good, and they wouldn't have brought in two more. Right? And so that's my answer to people who say, "Well, yeah, but..." I'm like, "No, there's no Yeah, but." And if people have seen the movie, "A League of Their Own," which a lot of people have, there's a scene in there with the young girl that comes with her friend, the Black girl and throws the ball and they tell her to leave. That's supposed to be based on Mamie Johnson's story. And she did try it want to try out and was not allowed to. And so ended up in the Negro Leagues instead.

Kelly 36:30

There's a great musical now about Toni Stone, which I had a chance to see. And I highly encourage that if people have a chance to see it they should.

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 36:38

Yeah. And there's a new one, there's a new film being worked on that's gonna look at all three of them.

Kelly 36:43

I want to talk a little bit about the sort of unintended consequences of integration of Major League Baseball. So of course, that's the goal all along is to have Black players playing with white players in the major leagues. But there's some things that are lost for Black communities, right, once that happens. So what does that look like once we finally get the color barrier start to break down?

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 37:07

It's a fascinating part that nobody ever wants to talk about, right? Because it feels like you shouldn't. And yes, when Rube Foster started the Negro Leagues, that was the idea, that they would, this was necessary until the day came when they could play. But Rube Foster's idea was never to was never what actually happened. His idea was to have whole teams being taken into major leagues, not an individual player here, an individual player there, right, that kind of thing. And those are two very different experiences. And the consequences are very different. And unfortunately, with integration comes a loss of something on so many levels that can never be replaced, right? And what people don't think about is okay, yeah, that's great. But here it was, was okay, so, Jackie Robinson, gets signed, Monte Irvin gets signed, Larry Doby, right, six or eight players. That's wonderful. But what happens is, of course, then all the fans follow to watch them, all the newspapers start covering them, which means what happens to those hundreds and hundreds of Negro League players who are still playing, who are never going to get that opportunity, because all you're doing is taking one or two of them. Well, eventually, those teams are all going to fold, which means all those people are going to lose their jobs. All those owners are going to lose their businesses, and all those ancillary businesses, all the Black hotels, all the Black owned restaurants, all of the right, and then they lived in these communities with these jobs. And you can't just take something that is a multimillion dollar industry, and remove it and replace it essentially with nothing, and expect that to be okay. And that's the part that people don't stop and think about. We didn't replace it. We didn't leave them with anything we didn't give them. And so it was great for the few that made it initially and all. But the loss on the other side, it mirrors what happened with Brown versus Board of Ed. Right. You integrate the schools and so the kids, what happened all those Black teachers, and hundreds and hundreds and thousands lost their jobs. And then we don't replace that. And so the infrastructure right is gone. And you don't want to think about it, but it's the reality. And then we look at the world today. And it explains a lot about cities and some of the infrastructure difficulty because we took away and gave nothing back. And then that's just the practical side. These pains were also on the players who were heroes in their communities. They were they what everybody looked up to. And so you're also removing some of that. So yeah, great. You've got one or two players now that you can watch in the major leagues, but you used to be able to go out and watch 30 or 40 of them and think that that could be you one day. And now there's one or two. And so is that really going to be you one day? Right? And so just when you start to pull it apart, the pieces of what was lost get bigger and bigger and bigger. And that's hard to talk about, because it never should have been that way in the first place. But it was, and unfortunately, we didn't really think through what the integration was going fully to mean, with because of the way we did it. I think if we had done it the way Rube Foster had hoped, where entire teams got, then businesses wouldn't have been lost, owners would have kept their teams, right. But that is not that is not the way it worked, unfortunately.

Kelly 40:42

Yeah, so you've been involved in this new exhibit that's going to be at the Baseball Hall of Fame, I think next month. Could you talk a little bit about the goals of the exhibit and what it's like to work on something like that?

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 40:54

Well, I can first say it's been amazing. For the last two and a half years, we've worked with them, and it's so excited to see it open. But at the end of May, biggest thing for people to realize is that this is not what museums typically do, which is they update an exhibit. And they'll refresh it. And this is literally, we take it all down start from scratch. And that's what we did. And been taken it is a complete new exhibit. Every aspect of it is new and the goal, a couple fold big keys, were first and foremost, to try to use this as an opportunity to look at Black baseball as a whole. So not just the Negro Leagues. In fact the Negro Leagues are a very small part, because Black baseball goes way back into the 19th century. And there are Black ballplayers still today. And so that's a big change from what had previously been there is that bigger story, and particularly bringing it up to the present and hoping that it continued to it will allow it to continue to grow that way. So it's not a static dead exhibit in that sense. And so that's the first big thing. I think the other is we wanted to use it as an opportunity to correct misconceptions, whatever those misconceptions, and so there's an opportunity to do that. But I think the biggest goal was to ensure that we took a slightly different approach. And that was to a pro and it comes out in the title in the choice of the title, "The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball," and it's that voices piece. Normally with most exhibits when you go to a museum, the story is told, yeah, with the artifacts, what the story is about those artifacts are generally told by the curators and the curatorial staff, they are making the well that's not what's happening here. The stories are being told using the words of those who were part of Black baseball, through their interviews, through quotes in the newspapers, all the things that can be verified, but that's how the stories are and so that I think is the most important and interesting thing about this exhibit that people are going to be surprised to be able to see and hear present day ballplayers, ballplayers coming alive from the past, with quotes, some from their direct interviews, others voiceovers, you know, quotes on the wall all about it's all their voices and not the voices of the curators.

Kelly 43:16

That's excellent. It's too bad you live right by The Football Hall of Fame instead of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 43:21

Yes, that is true, though. I was just there last week.

Kelly 43:24

So you have written and edited a number of books about baseball and Negro Leagues. Can you tell people how they can find your work?

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 43:33

Sure. So most of it nicely is available on Amazon. So if you just look up my name, you're gonna find the most prominent one is just called, "The Negro Leagues, 1869 to 1960." And then the others, on various aspects of Black baseball, are all available on Amazon, or through McFarland. McFarland Publishing out of North Carolina is who has published most of and so they're available there. McFarland also publishes a journal called, "Black Ball," which I've been the editor of, since their very first book that came out. And so those are available through McFarland Publishing. Yeah, those are the main ones. And then I've helped edit it. So it's not me, it's just an editing. But I did do a fun project with SABR, the Society for American Baseball Research. We did two companion books on the 1986 Boston Red Sox and the 1986 New York Mets. I edited, of course, the New York Mets side of that, which was fun.

Kelly 44:25

Excellent. Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 44:29

This was fun. It's always nice to get an opportunity to, I've really appreciated the thought of focusing too much people focus on stats, and I will say stats only tell part of the story. And if that's all you got, you really don't have the full story. And so they can't be used, particularly with the Negro Leagues to understand because the stats miss, "Well, why are there only 60 games when we know they played 200?" I don't understand that right, that comes out of the story. And so I think that And then I think the biggest coolest is really understanding that it's about more than just stats and numbers. But all history is about more than just stats and numbers.

Kelly 45:09

Yeah.Well, Leslie, thank you so much. This was just great I enjoyed your book on the Negro Leagues, and it's been great to speak with you.

Dr. Leslie Heaphy 45:17

Well thank you very much, Kelly. I appreciate the opportunity. It's been a lot of fun.

Teddy 45:39

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode, and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai