Mary Seacole

When the United Kingdom joined forces with Turkey and France to declare war on Russia in March 1854, Jamaican-Scottish nurse Mary Seacole decided her help was needed. When the British War Office declined her repeated offers of help, she headed off to Crimea anyway and set up her British Hotel near Balaklava. The British Hotel, which opened in March 1855, was a combination general store, restaurant, and first aid station, and the British soldiers and officers came to love Mary and call her “Mother Seacole.”

Joining me in this episode to help us learn more about Mary Seacole is historian and writer Helen Rappaport, author of the new book, In Search of Mary Seacole: The Making of a Black Cultural Icon and Humanitarian, which will be released in the United States on September 6, 2022.

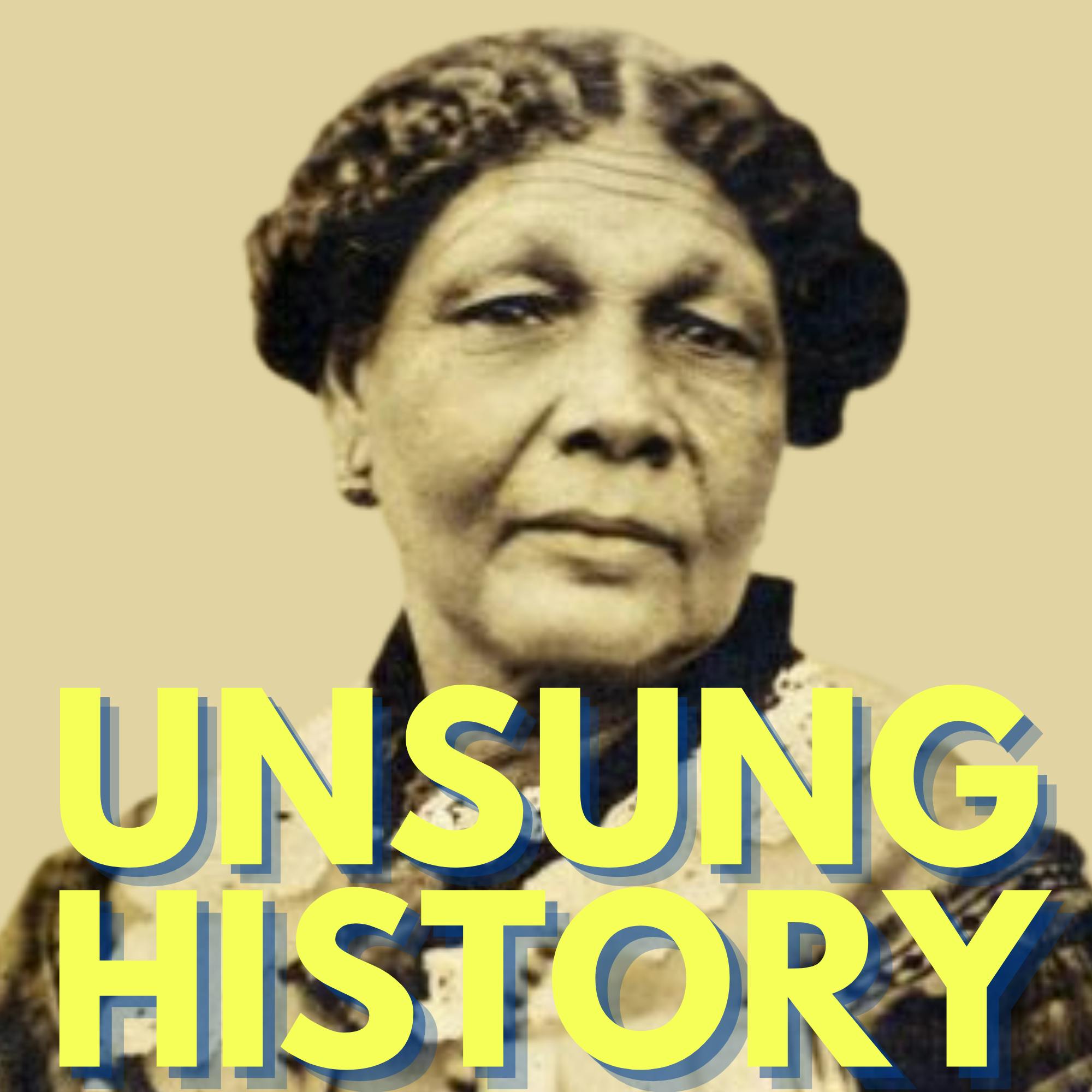

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image is a photograph of Mary Seacole from an unknown source, believed to be dated around 1850; it is in the public domain.

Additional Sources:

- “Mary Seacole & Black Victorian History: Remarkable Women in Extraordinary Circumstances,” Helen Rappaport.

- Mary Seacole Trust.

- “The Crimean War,” by Andrew Lambert, BBC.

- “Crimean War,” History.com

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

In today's episode, the third in our four episode detour into British history, we will be discussing the life of Mary Seacole. Mary Seacole was born near Lakovia, Jamaica sometime around 1805. Various sources list her birth date as November 23, 1805. But the source of this birthdate is unknown, and there's no documentary evidence to back it up. Mary's parents were Jamaican Rebecca Grant, and Scottish John Grant. It appears that her parents were not married, and that it was coincidental that they shared a last name. This kind of relationship between a white man and a Black or mixed race woman would not have been unusual in Jamaica at the time. And it may be that John Grant, who according to Mary was a soldier from an old Scotch family, did acknowledge and provide for Mary. Mary's mother, Rebecca ran a lodging house in Kingston and she also acted as a doctress. It's unknown how Rebecca learned her doctoring skills, but she passed them on to Mary. Mary says in her memoir that she helped her mother treat invalid officers and their wives from nearby Up Park and Newcastle Station. On November 10, 1836, Mary married a white Englishman named Edwin Horatio Hamilton Seacole in Kingston. They moved to Black River, near where Mary was born, and opened a store. At some point, they moved back to Kingston, and within a few years, Mary suffered a number of tragedies. A disastrous fire in Kingston in August, 1843, destroyed Mary's home and nearly cost her her life. In October, 1844, Edwin died after having been sickly for a long time. And then in 1848, Mary's beloved mother, Rebecca died. On August 16, 1848, Mary was baptized into the Roman Catholic religion, stating her name then as Mary Jane Seacole Grant. Unfortunately, her birthdate is not listed on the baptism certificate. In 1851, Mary traveled to Cruces, Panama, to help out her brother, Edward, who had opened a ramshackle boarding house, which he called The Independent Hotel. Shortly after Mary arrived, the town was struck by a cholera epidemic, and Mary was kept busy treating those afflicted. She would charge the wealthy for her services when she could, but she treated the poor for free, a practice she would keep up throughout her life. Mary herself contracted cholera in Panama, from which she recovered. On the other side of the world, in July, 1853, the Russian army invaded two Turkish held territories that would later be part of Romania, in support of Tsar Nicholas I's demand that the Eastern Orthodox people living within the Ottoman Empire should be under his protection. In October, 1853, Turkey declared war on Russia, and on March 28, 1854, England, already allied with Turkey, declared war on Russia, one day after France had done so as well. Mary decided she was needed. She sailed to England, arriving in Southampton, on October 18, 1854. By November, the British Army had suffered tremendous losses from the fighting, but also from sickness and malnutrition. On November 4, 1854, Florence Nightingale and a group of 38 nurses arrived at the Army Hospital in Scutari, Turkey, which to that point had been unclean and poorly supplied.

In England, Mary offered her services to the War Office, and offered to join Florence Nightingale's nurses, but she was rejected by every official she spoke with for racist reasons. She decided to head to Crimea anyway, and left England on February 15, 1855. With her on the ship, was her daughter, Sarah. Acute listeners will note I haven't mentioned Sarah until now. That's because it's not until now that Sarah, who was apparently around 15 or 16 years old at the time, appears in the record. I'll speak with today's guest about the mystery of Sarah. On the way to Crimea, Mary stopped at Scutari, where she met Florence Nightingale and stayed for one night in the hospital. But she quickly moved on to Crimea. Mary and her business partner, Thomas Day, set up what Mary called a hotel near Kadikoi, close to the British camp, near Sebastopol. The British Hotel, which opened in March, 1855, was both a general store and restaurant as well as Mary's headquarters, from which she nursed soldiers and set out as a sutler, selling goods and providing nursing services to soldiers in the field. The soldiers in Crimea came to love Mary, and they called her "Mother Seacole," writing home to their families about her kindness. The Crimean War ended on March 30, 1856, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. With the departure of the army, Mary, along with Thomas Day, tried to sell their stock, but they found themselves facing ruin. By August, 1856, Mary was back in London, celebrated for her services in Crimea, but destitute and summoned to bankruptcy court. The following year, Mary published a 200 page memoir called "Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands." Although it's referred to in many places as an autobiography, the focus is not on Mary's whole life, but rather on her time in Crimea. Mary's many military friends in London raised funds for her, and she spent much of the rest of her life moving around, trying to find places where she could be helpful, in London, Jamaica, Panama. Despite attempts, she was not able to follow the military to any future conflicts. Mary Seacole died on May 14, 1881, in Paddington, London. She was buried in St. Mary's Roman Catholic Cemetery in London. Her grave was restored and re-consecrated in 1973, after the editor of The Nursing Mirror found the grave that had been forgotten and overgrown. Joining me now to help us understand more about Mary Seacole, is historian and writer Helen Rappaport, author of the new book, "In Search of Mary Seacole: The Making of a Black Cultural Icon and Humanitarian," which will be released in the United States on September 6, 2022. Hello, Helen, welcome. Thank you so much for speaking with me today.

Helen Rappaport 9:47

Well, thank you for inviting me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:49

Yeah, so I was really excited to read this book. I thought it was really fun. As an American, I did not know anything about Mary Seacole, and so it was it was great to learn about her. I wanted to ask how you first got interested in the story. I know you've been pursuing this for a very long time now in the midst of writing other books. So I wanted to hear sort of the the origin of your interest in Mary.

Helen Rappaport 10:13

Well, I should start by saying, I think it's really good that you've got no preconceptions about Mary. Because here in England, one of the reasons it's taken me so long, is I have fought and struggled with a lot of sort of mythology and entrenched ideas and misunderstanding and misconceptions about Mary, her life, and what she did and what she didn't do. And it's been necessary over this period that I've worked on her to try and unpick a lot of stuff. But how I first became interested in her, dates back right back to the turn of the millennium, because I was asked by an American academic publisher called ABC-Clio; they do a lot of reference books for colleges and libraries, they're not really mainstream trade as such; if I'd be interested in doing an encyclopedia of women social reformers. I'd done a couple of other books for them. And at the time, I said, "Yes, I'll do it, but I don't want it just to be a load of American and British white women," because with a subject like that, you can end up with all the obvious candidates: the suffragettes, Florence Nightingale, etc, etc. And I made it an objective of mine, to try and find as many women of color in the third world outside America and Britain and Europe as I could. And so in order to do that, I had to slightly kind of stretch the parameters of what I meant by social reform. Because first and foremost, Mary Seacole most definitely was not a social reformer. She was an inspirational figure, a pioneer who has since inspired many, many people, many women and men in the nursing and medical profession. So I also particularly wanted to find women in the West Indies, women of color. And I came across her, a passing mention to Mary Seacole. Now back back in 2000, hardly anything had been said about her. A few people had mentioned that she'd written this memoir which the feminist movement had rediscovered in the mid 80s. And luckily, a small press in Bristol had republished her "Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands," but really, there was very little available on Mary. But at the time, and I was intrigued by her life, because reading that memoir, and it is only a memoir; people mis-describe it as an autobiography, it isn't, it only covers about five years of her life. Within that memoir, there are so many gaps and so many obfuscations where Mary is kind of economical with the truth. I thought there's a lot more to this woman's story I want to find out. So I started doing some research on Mary and I became more and more intrigued, and I thought, "I'd really like to do her biography." And then unfortunately, I very quickly discovered someone else that had the same idea, and had actually signed one. So obviously, the agent I was with at the time said, "Well, there's no point doing a rival biography, I'll never sell it." So I said to her, "Well, I'm going to carry on doing Mary as a hobby, because no one's going to find all there is to say inside a year," which was this when this other one was due out. So I basically over the years have come and gone on to other things, written other books, tried to earn a living, done all kinds of other projects. And periodically, I'd go back to Mary every few months or so even, you know, every year or so, and try and fill in another gap somewhere. So it's been a long, long process of trying to uncover her story. And what has made a difference is that piece by piece, bit by bit, in the last 20 years with the growth of the internet, so much more has been digitized in terms of the contemporary newspapers. And that is largely where I built up and reconstructed the whole story of Mary, certainly in Crimea, but also bits and pieces of the rest of her life because you can't just go into a library and pick a few books off the shelf and find some useful secondary sources that are going to tell you about Mary because they don't. And the frustrating thing is and it's still going on now is that if you go on the web and search you will find an awful lot of sources all repeat each other and all repeat the same errors. So I just I kind of become this little one woman campaigner to get to the truth because I hate not knowing all the facts. I want to get to the truth of Mary's story because I feel she deserves it, and because she is such an extraordinary personality.

Kelly Therese Pollock 15:10

Yeah, and one of the things I love about this book is you talk about that search. So as the title of the book suggests, it's not just, you know, a biography of Mary, although it's that too, but it's also about you looking for the sources and trying to find the truth. So can you talk a little bit about the you've started to talk about the struggles of that, but especially the struggles of finishing this book, during a pandemic, when at times you were in lockdown, and couldn't travel and couldn't get to where the sources were?

Helen Rappaport 15:42

Well, luckily, I finished the book. I delivered the book in in March, 2021, I think it was. And fortunately, with Mary, I had done so much research before the pandemic broke, that I really had done all the groundwork. The only thing that was missing, and I do regret it, is I couldn't get to Jamaica. But having said that, a lot of the Jamaican records are incomplete. They haven't survived, or they were never kept in the first place, especially when they relate to people of color. Obviously, I wanted to go to Jamaica to get a sense of the place and sense of Mary's homeland. But in the end, actually, what I had to do, I had no other option during the pandemic was I had to hire a genealogist in Jamaica. And in the end, it actually probably was more productive that way, because Anne Marie had been and had specialized in Jamaican genealogy for many years, and it's not that I didn't particularly need her for a lot of the story. But I particularly wanted her to get get into the sort of secondary sources, things like poll books and tax rolls and records of ownership of properties in Kingston. And also the most important search of all that she did do for me, and I'd spent 20 years looking, was to find, eventually find Mary's missing baptism, which was so gratifying. But as such during lockdown, I had accumulated an enormous archive of material, something like 10 ring binders, a four ring binders, you know, a whole shelf full, full of information. So it was all there waiting to be written up. And the one thing that it always sort of panicked me was the thought of, "God, what if I fell under a bus tomorrow or, you know, or died and my work wouldn't be written up?" I wanted to be sure that I'd given my research to the world. Oh that sounds pompous. But you know, that I'd shared my research so that other people could look at it and see if they could add anything, because I hated the thought of it all languishing in those files, gathering dust, you know, never being published. So, in a way, the pandemic when it happened, focused my mind. I had nothing else to do, but write that book. And as it turned out, I wrote two books, because at the time, America didn't want the Seacole biography. American publishers were headed hesitant about it. So I then back to back wrote a completely different book for the American market, which is about the Russians who went to Paris.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:38

One of the things as you were mentioning, you, you wanted to get your research out so that people would know but then they can also sort of know you as the person to contact if they find things. And so you had this really fortuitous thing happen many years ago now, where someone contacted you with a painting that was unknown of Mary's. I wonder if you could talk about that? It's fascinating story.

Helen Rappaport 19:04

The painting is is what has driven me all these years in a way because I felt, I know this is gonna sound so corny. But when I when I was asked to identify that painting and the JPEG pinged into my inbox just before Christmas, 2002; as soon as I opened it, and saw that image, I had an absolutely consuming sense of mission. And, you know, I felt yes, there's no doubt it's Mary. It was sent to me by a military historian who had been asked by a friend of a friend who bought it at a boot sale, can you believe that? You know, you know, like a yard sale in America, we call them boot sales here. And the minute I saw that painting, I knew somehow or other first of all, I knew it was Mary, without shadow of doubt, that I had to make sure it didn't disappear, in the sense of being sold into a private collection, disappearing abroad, going into air conditioned vaults somewhere. And I became completely panic stricken that no sooner had I found it, then I would, it would disappear again. So I went on this little campaign to track down the man who got hold of it, the dealer, and I went to see him and I didn't in any way mislead him or con him, I said, "This is a historically significant painting for women, for history, for Black people." But no one knew who the artist was, it would have been quite different if it had been by a known Victorian artist. I would never probably have been able to buy it. It would have immediately gone to auction in London somewhere. But because the artists no one had ever heard of him, was unknown that completely devalued it in that respect. And at the time, interest in Mary was only just beginning to build. So it's a long and complicated story. But basically, I eventually got to meet the dealer, who at the time was living only 15 miles up the road from me in Oxfordshire. And I persuaded him to let me buy the painting because he was humming and hawing a bit and being tricky, and he'd muttered about,"Oh, I'm gonna send a fax of it to New York," and, and my blood ran cold when he said that. I thought, "Oh, God," you know. Anyhow, but he was actually a very honorable bloke. And he said to me, "Well, I actually do care about where some of the pictures I acquire, go," and he bought and sold all the time, all the time. And he could sense that I was honorable, and that my passion was to say, God, this again, it sounds pompous, but just save her for the nation. Because I wanted to make sure that painting was somewhere where everyone could see it, who was interested in, Black history, women's history, nursing, you name it, the Crimean War. And I knew immediately there was only one possible home for that painting. It was the National Portrait Gallery in London, because there's a whole room of paintings of all the worthies and dignitaries connected to the Crimean War, including, of course, Florence Nightingale. And there it is now up on the wall in that room, or she was when I last looked at, I think they're reorganizing things. And so it was my ambition that as soon as I got, actually finally got the painting, and I had to borrow the money to buy it and tell lies to my bank manager, returned, I needed to do house improvements. I was a single parent at the time, and I didn't have the money at all. The first thing I did within two weeks of finally laying hands on it, about six months later, I took it to the National Portrait Gallery, first of all, to have it authenticated. So they did X rays and pigment tests. But the extraordinary thing was about that painting, I searched the Heinz Archive at the National Portrait Gallery, which is a huge archive of literature and books about art and painters, not a single solitary mention anywhere of the artist's name that was on the back, A. C. Challen. Now I did the genealogical research and found out who he was and filled in a bit about his life. And I've still not discovered another painting by him anywhere. So it's absolutely extraordinary, that that unique portrait, there doesn't seem to be another known work by the artist of that unique portrait. I would love one to come to light. There must be someone somewhere who's got something on their wall that's got A. C. Challen on it, and it hasn't occurred to them or hadn't made the connection. And mind you, he had only been an art student when he painted that portrait of Mary. I don't think he went to a formal art college. He probably just trained perhaps with another artist or was self taught. But he was so new in his career as an artist it may be that's why there's nothing else by him because unfortunately, he died young.

But that is part of the search for Mary. It was that painting, Mary's story. And the reason I wrote the book in the way I did well, first of all, you can't go do a conventional biography of Mary, because there's too many gaps and expanses where you don't know a lot about what she was doing. I wanted to take the reader with me along the way, and sharing the research and then the, you know, the discoveries, the disappointments, the dead ends because if there's one thing I've learned from all the books I've written and doing talks at literary festivals, people love to know how you do it. Many people said to me, "Well, how do you go about researching, you know, someone's this story or this person's life?" And I think it explains the process that you can't just miraculously walk into the British Library and find everything sitting on a shelf, or do a few clicks on the internet and it's all there waiting for you; because it isn't. It's hard work.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:31

And one of the things that you were searching for, and the thing that makes Mary identifiable, so identifiable in that painting, is the metals that she has, these three, possibly four medals that she's gotten. Can you talk some about that and the the sort of unknown provenance of how she got some of them?

Helen Rappaport 25:49

Well, I'm afraid the whole issue of Mary's Crimean War medals is a massive hot potato, because it's been the most contentious aspect of her career, certainly, in terms of these are the military historians, and in particular historians of the Crimean War. And I've had, you know, over 23 years, I've had endless discussions, quite lively ones with some of the members of the Crimean War Research Society, who very rightly dispute there is no official documentation for any of the medals Mary had. Now the first and most important thing is that no woman, no woman at all in Britain was awarded the Crimean War Medal by the British government, not even Florence Nightingale. That was a hard and fast rule. And in fact, the British government were quite sniffy about even foreign governments awarding medals to participants in the war. So for example, they got rather annoyed when apparently, I mean, the press said it was in the contemporary press, the Sultan sent Mary a medal, because she helped some of the Turkish soldiers in Crimea and you know, she new Omar Pasha, the head of the the Ottoman troops there. Now the Sultan sent her a medal. There's no documentation, there's no official record, but at least two or three war correspondents mentioned the fact, but with the Crimea medal with the French medal, and a possible Russian medal, we're not sure. A possible Sardinian medal, we're not sure. There was a small Sardinian contingent among the allies. Everyone's looked, and there's no evidence. I spent hours going through all the medals documents in the National Archives at Kew, looking for any mention of Mary being in some way being granted the Crimea medal, there's nothing. And the only conclusion I've been able to come to and we found no documentation for any medals anywhere, French, Russian or anything. The only conclusion I can come to certainly with the British Crimea medal, is that Mary had so many admirers and patrons, not just within the top brass of the military who were out there and who knew her, but also the aristocracy that you know, she had patrons and supporters, and most importantly, the royal family. Because the Queen's cousin, the Duke of Cambridge was out in Crimea. Edward of Saxe-Weimar out there, and Count Gleichen, the Queen's uncle was out there. And there, obviously various people within the royal family had reported back to Victoria, about the heroic doings of Mrs. Seacole. She must have read all the press, and seen all the accolades for her. The only conclusion I can come to is that everyone felt Mary should be given something for her her contribution to the war effort. They felt she deserved an accolade of some kind. And what better accolade would there be for someone who was so proudly patriotic and absolutely adored and admired the you know, the Empire and the Queen? What better thing than to give her a medal? So, I think basically, it was given to sort of via the back door. A private arrangement was made, and people said, "Look, give her a medal. Just let her have a medal." Because Mary proudly paraded around London for decades afterwards, wearing her medals or the miniature versions because you know, they a lot most Crimean veterans wore miniature medals which were smaller and less heavy than the great big official ones. She many people talk of seeing how walking up the Tottenham Court Road wearing her medals. And the medals unfortunately are described, variously described in different press accounts. Sometimes there's three, sometimes there's four, there was a lot of confusion. There was at one time three surviving medals of hers, in Jamaica, in the I think, the Jamaica Institute, but there was an earthquake there in 1908. And one of them got lost in the debris. There are two surviving medals still in Jamaica. One of them is the Turkish Medjidie, but the others have been lost. So it's something I tried very hard to unravel. But unless some new evidence comes to light, I can't get any further than I have.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:41

So when you're thinking about Mary, when we're thinking about what she did in the war, she was not, of course, a trained nurse. She was trained by her mother, but she wasn't trained in like a medical school or something. But I think that that's important, as we're thinking about that, to think about the context of what the medical field was like at the time. So I wonder if you could talk about, you know, for nurses like Florence Nightingale and those who are at the hospital or for the doctors who were operating, like, what was the state of the medical field around this time, you know, in in comparison to what Mary was providing?

Helen Rappaport 31:20

Well, first and foremost, no one can accuse Mary of not being a nurse because there was no nurses training. It's as simple as that. But official, formal training of nurses was set up by Florence Nightingale at St. Thomas' hospital, after the war, as a result of all the heroic work women had done out in Crimea. When the war broke out, and they were desperate for nursing volunteers because at the time until then, all the army had had were a few kind of male orderlies and kind of stretcher bearers or the doctors, the basic establishment allopathic doctors. The only women available to nurse as such at the time the war broke out, were either nuns from some of the nursing convents and there were one or two in and around London. There were quite a few Irish nuns, who were experienced in nursing the sick poor. And of course, in in and around France and Asia Minor, there was a whole network of convents of the Sisters of St. Vincent DePaul, who had been nursing the sick poor for decades, for centuries. But as such, there was no nurses training beyond benevolent nuns who, who learnt almost learned on the job nurse, nursing the sick during epidemics, or what were known as the hospital nurses who worked in the general hospitals, but they weren't nurses who took us took the pulse and administered medicine and did all that more sophisticated things that we think of nurses doing now. The hospital nurses effectively were dogsbodies. They filled the mattresses with straw, they emptied the slop pails, they fed the patients, and that was pretty much the limit to their nursing. So there was as such, no official nursing training, but in comparison to what was on offer in Britain, and in most of the western world, out in Jamaica, there was this --and, the West Indies as a whole--on the plantation, a whole school of these doctresses, as they were referred to had had grown up. And as a result of women of color and Black women being recruited to nurse the sick slaves on the plantations. And the thing about Mary's nursing background, which she learned at her mother's knee, was these women didn't rely on allopathic medicine, on on opium and opiates and laudanum and all the heavily sort of soporific drugs that medical establishment used. They drew on the natural pharmacopoeia. So as such, they were herbalists. They made their own concoctions out of the natural indigenous plants and wood barks and spices. They were not homeopaths. That's a different thing. But interestingly, one of the things that happened after the war, one of the reasons Mary was so well patronized when she came back to Britain was that homeopathy was beginning to grow, just in the late 50s. And a lot of people who patronized the homeopathic movement, admired Mary and and they even probably privately sought her help for her more holistic cures. So Mary and the West Indian nurses in general and there were many of them, who helped nurse sick white people in Jamaica and elsewhere in the Caribbean, earlier in the 19th century, they had a tremendous reputation for being very very good, kind, efficient caregivers. So it's that tradition that Mary came from as a nurse, as a caregiver, as a much more all around thing than just someone who mopped the fevered brow.

Kelly Therese Pollock 35:24

I want to ask about Mary's daughter, Sally. And so this is a another mystery that you that you tried to unravel throughout the book that it is frustrating that we don't know more. So could you say just a little bit about Sally, what what we do know about her and then sort of what what we just can't know about her?

Helen Rappaport 35:43

I'm afraid frustratingly little. The problem with Mary was Mary's daughter, well, Sarah, Sally, I call her Sally because that's how she was affectionately referred to by the French chef Alexis Soyer, who was in Crimea to help improve the nutrition of the troops. We don't know for sure what's what name she went under. Okay, if she was Sarah, Sarah, Sarah who? Sarah Grant? Sarah Seacole? Sarah Bunbury, by the possible man who fathered her? I'm not you know, we I'm not 100% sure that Colonel Bunbury, the Colonel Bunbury that Florence Nightingale alleged Mary had an illegitimate child by, was she right? Did she have the right man? I mean, Nightingale might have just heard, had misinformation passed on to her. I've tried to make it stack up. But there's so many problems with this possible illegitimate daughter and of course, one of the biggest issues is Nightingale said she was about 15 in Crimea, well, that would have been 1855. So we're looking at a birth at about 1840 Well, in 1840, Mary's husband was still very much alive. So people have said to me, "Yeah, but you've got it wrong. It was she was probably Sally Seacole." Why, why would Mary not mentioned her daughter if she's the legitimate child of a legitimate marriage?" No, that doesn't make any sense whatsoever. Sally is, Sally was not Seacole. I found one possible passenger listing slightly garbled one when they arrived in Malta on the way out to Crimea, which talks about a Mrs. Grant and a Mrs. Sencole. Well Mary's name got muddled or misspelled all the time. Now, Mrs. Miss Grant, what if Sally was Sally Grant, Sarah Grant? Well, as an impossibly common name, impossibly common name without a middle name or some piece of information attached to it a proper date of birth, I had nothing to go on. And the awful thing is that Mary is completely airbrushes out all her relatives pretty much except for a passing reference to her brother, in her memoir, for very obvious reasons. Sally is disguised as her little maid when she took her to Panama with her. We don't know anything about her except a couple of places where I think I spotted her where she was hiding in plain sight, and probably was with Mary certainly till about 1871. But I just cannot find her. And thing is, I don't really know what I'm looking for, what name? I've tried every permutation. You would not believe how many hours I've sat on Ancestry and Find My Past, searching censuses, baptisms, registrations, every possible permutation of names, trying to find someone who might just fit. And I've drawn a complete blank, as Sally has totally eluded me, and it really breaks my heart because I don't like not being able to say what happened to her, because she comes across as such a charming and animated and likeable personality. And all, quite a few soldiers mentioned her and said how delightful she was. And I think, "Gosh, isn't it awful that Mary felt obliged to completely deny her own daughter's existence, because of morality of the times?"

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:30

Yeah. We should talk then about kind of why Mary was forgotten, and then why Mary was remembered. It's so I, you know, I wonder if you could talk some about you know, we all even you know, in the US, everyone knows who Florence Nightingale is. She's been known since her life. But But Mary, who was just as important during the Crimean War, it you know, was forgotten for so long. So can you talk a little bit about what you think reasons for that are?

Helen Rappaport 40:01

Very simple reasons. And I get annoyed when people say, "Oh, she was deliberately airbrushed in the record because of racism." It's not as simple as that. Mary had no paper trail. There was no legacy for Mary. You go all over England or if you did after the Crimean War, every other town had a Nightingale Street, or an institution, or a statue, or a bus or something mentioning Florence Nightingale's name. You know, the whole country, referred to her as "The Lady with the Lamp" which she hated. She hated that sobriquet. But the bigger issue is Florence Nightingale left 14,000 letters. She became a very important leading social reformer of social public health reform, military health reform. She was a gifted statistician. She published notes on nursing after the Crimean War, which has never gone out of print. What did Mary have to compare with all that to keep her name alive? And of course, okay, Florence didn't have children, but she had family and admirers to keep it all going, Mary, Mary's only possible child disappears from the record, the one person who might have kept her legacy going. So there was no one to carry on the memory, to pass the torch, as it were, except the old soldiers who knew Mary in Crimea. And, you know, for the first few years after the Crimean War, she was celebrated, she was always in the press of, you know, until about 1859, when she went back to Jamaica for a while. But of course, as time went on, because Mary didn't publish a book on nursing or an account of her medical practice, although there was that slim memoir, it only covered just the war, as time went on, and the old soldiers who'd shared her story, who'd known her in Crimea, who'd been nursed by her, as they began to die, the memory was lost. And so the last mentions of Mary, she'd had quite a lot of papers covered her death in 1881. Although, of course, it was really just The Times entries syndicated. But it even you know, it was in the American press, the British colonial press, in Australia, New Zealand, India. A lot of papers around the world did mention her when she died. But after 1881, after her death really, things really did drop off very quickly, apart from occasional very late memoirs, or letters or diaries, being published that mentioned her, and also a couple of kind of rather worthy Christian collections of about, you know, who wrote women that talked of Mary. So it just got lost, because there wasn't anyone to keep the flame burning, and because she didn't have a huge body of letters and diaries and paperwork that could be shared and published and studied. So Mary's rediscovery? Well, there were there was a flurry of a mention of her in in 1954, on the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of the war, where one or two people in Britain said, oh, people ought to and this was the beginning of the Windrush immigration of Jamaicans on the ship, the Windrush from Jamaica, and, you know, people were getting very concerned about this, and there was much discussion about it. And one or two people wrote to the press and said, you know, people should look at Mary Seacole as an example of the good colonial subject as it were. And but then that died down and things really didn't get going until the feminist movement began rediscovering a lot of forgotten women, not just Mary of course. And in the mid 80s, a couple of women involved or connected to a library in Brent in in North, sort of this outer suburbs of London, suggested an exhibition about Black history. And one of the things offshoots from that was the idea that they moved to that Mary's memoir should be republished because it had languished since 1857. It was only brought out in a very cheap, very flimsy paper, paper covers, you know, cardboard covers, not the kind of book that would have survived very long. In fact, there were only about five or six copies across Britain in in libraries. So a press in Bristol called Falling Wall Press, reprinted the memoir, in 1984. And from then on, it really began to gather and then the big big momentum of course came at the end of 2004. There was vote on British the greatest Black Briton, which Mary won. The following year was her bicentenary, which is the year I unveiled the portrait, the other biography came out. And that's really when things are snowballed, because Mary then was taken on to the national curriculum for our school children, more and more people began to study her and write about her. I mean feminist women's historians have been writing about her since the 90s, really, but only in feminist journals, and not particularly in the mainstream. So since 2005, Mary's triumphant rise been unstoppable, pretty much.

Kelly Therese Pollock 45:44

Well, there's a million other things we could talk about, but people need to just go read the book instead. So tell everyone how they can get your book.

Helen Rappaport 45:52

The book is going to be published in New York by Pegasus Press on September 6. And I do urge people, anyone interested in Black history, women's history, history of the Crimean War, or you know, of just unusual, extraordinary and forgotten women, do read it, because in the book, I take the reader on a journey through history and how you dig out the facts for difficult subjects who many people will give up on and say, "Oh, there's nothing to find." But there is, if you stick at it long enough. I mean, it took me 20 years on and off, but I think I've found as much as I can hope to find short of some long lost or hidden archive or family papers turning up that mention Mary.

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:40

Yeah, and I'll put a link in the show notes. It's a great book. I think everyone should should go and buy it.

Helen Rappaport 46:46

Well, thank you very much and do spread the word, won't you?

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:50

Yes. Is there anything else that you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Helen Rappaport 46:53

Just to say that I'm never giving up. Okay, the books out, it's here out here. It's out in the UK, and in America, but that doesn't mean I stopped, it never stops. My search for all my subjects never stops. I revisit them constantly looking for new information because one of the great joys of my life is digitized newspapers. I wile away many a winter's day, long, dark rainy winter's day here in deepest Dorset going through the digital newspapers, and there are always new and fascinating things to find. So I'm optimistic that yet more still might come out about Mary, bit by bit little sightings, little snippets. But if anybody knows what happened to her daughter, I am just longing, longing to solve that particular puzzle more than all the others.

Kelly Therese Pollock 47:50

Well, Helen, thank you so much for speaking with me. It was really great to learn about Mary.

Helen Rappaport 47:55

Thank you.

Teddy 47:55

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Dr Helen Rappaport is a Sunday Times and New York Times bestselling author and historian specialising in the period 1837–1918 in late Imperial and revolutionary Russia and Victorian Britain.

She has written 14 books covering her broad range of historical knowledge, and is a regular contributor to history and documentary programmes for TV, radio and online media such as Netflix. As a historical consultant she most recently worked on the first two series of the ITV drama Victoria.

As a linguist with a degree in Russian Special Studies, she has also worked for many years as a literal translator in the theatre, specialising in the plays of Anton Chekhov.

In 2016 Helen was awarded an Honorary D.Litt by her old alma mater, Leeds University, for her services to history.