Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was born in China in 1896 but lived most of her life in the United States, where, due to the Chinese Exclusion Act, she had no path to naturalization until the law changed in 1943. Even though it would not benefit her for decades, Mabel Lee worked for women’s suffrage, leading the New York City Suffrage Parade on horseback at the age of only 16. Lee was the first Chinese woman to earn a PhD in Economics in the United States, graduating from Columbia University in 1921 with a dissertation entitled: “The Economic History of China: With Special Reference to Agriculture,” and then spent her life helping the Chinese community in New York City through her work with as director of the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City.

Joining me to help us learn more about Mabel Lee is Dr. Cathleen Cahill, Associate Professor of History at Pennsylvania State University and author of the 2020 book Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement.

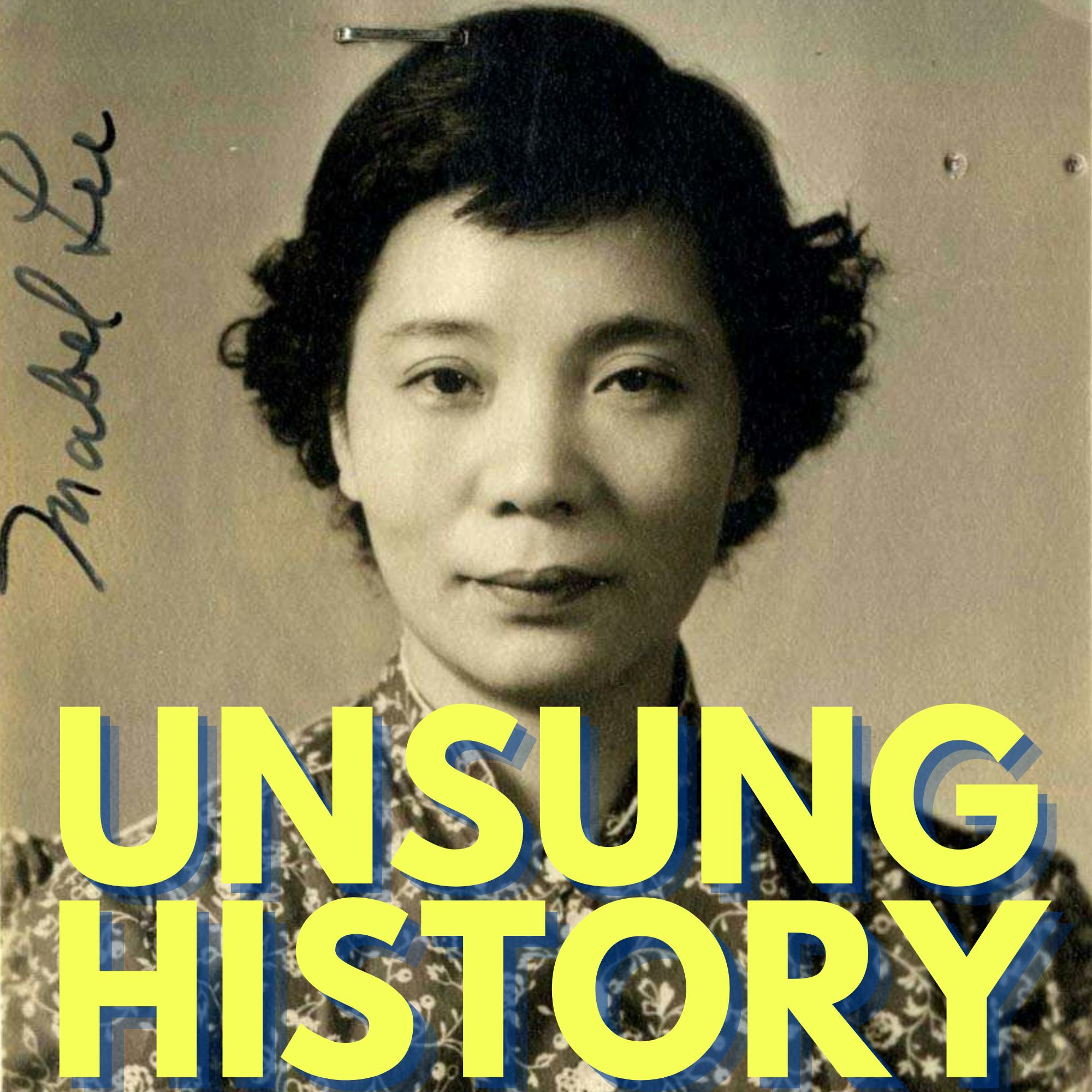

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image is “Radiogram; 6/26/1937; Case #12-943; Chinese Exclusion Act case file for Mabel Lee (Ping Hua Lee);” from Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files, ca. 1882 - ca. 1960; Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group 85; National Archives at New York, New York, NY.

Selected Sources:

- “Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee,” National Park Service

- “The 16-Year-Old Chinese Immigrant Who Helped Lead a 1912 US Suffrage March,” by Michael Lee, History.com, March 19, 2021

- “Asian American Legacy: Dr. Mabel Lee,” by Tim Tseng, December 12, 2013.

- “Overlooked No More: Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, Suffragist With a Distinction,” by Jia Lynn Yang, The New York Times, September 19, 2020.

- “Mabel Ping-Hua Lee ’1916: A Pioneer of the Suffrage Movement,” by Lois Elfman, Barnard Magazine, Fall 2020.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

Today's episode is about Mabel Ping-Hua Lee. Mabel Lee was born in China in 1896. Her missionary father moved to the United States when she was very young, and at first, Mabel and her mother remained in Hong Kong, where Mabel learned English. When she won a scholarship to study in the United States, she and her mother were able to get US visas and they joined her father in New York City, where he was a minister at the Morningstar Mission. The Lee family lived in a tenement at 53 Bayard Street in Chinatown by 1905. Mabel Lee attended Erasmus Hall Academy in Brooklyn. In 1912, suffragists in New York City planned a parade to advocate for women's voting rights. In the parade on May 4, 1912, Mabel Lee, then only 16 years old, helped lead the parade on horseback from its starting point in Greenwich Village. The parade drew a crowd of 10,000. Anna Howard Shaw, who was then president of the National American Women's Suffrage Association, or NASA, followed Lee carrying a banner that read, "NASA Catching Up with China." Lee began her studies at Barnard College in New York City. Barnard was the all women's school founded when Columbia University refused to admit women. At Barnard, Lee majored in history and philosophy. She joined the debating club and the Chinese Students Association, and wrote for the Chinese Students Monthly. In May, 1914, Lee wrote an essay in that publication titled, "The Meaning of Women's Suffrage," in which she argued that suffrage for women was necessary to a successful democracy. In 1915, Lee gave a speech at the suffrage workshop put on by the Women's Political Union. The speech was titled, "China's Submerged Half" and was covered in the New York Times. In it, Lee argued, "The welfare of China and possibly its very existence as an independent nation, depend on rendering tardy justice to its womankind, for no nation can ever make real and lasting progress in civilization, unless its women are following close to its men, if not actually abreast with them." After Barnard, Lee attended Columbia Teachers College, where she earned a master's degree in educational administration. In 1917, she was admitted to Columbia University for a doctorate in economics. Although Columbia College did not start admitting women to study for undergraduate degrees until the 1980s, it had been admitting women in small numbers to graduate programs since the 1880s. At Columbia University, Lee was the vice president of the Columbia Chinese Club, and associate editor of the Chinese Students Monthly. In 1917, the state of New York gave women the right to vote, but because of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Chinese immigrants like Lee and her family were ineligible for naturalization, and thus could not be granted the vote. When Lee graduated from Columbia, in 1921, she became the first Chinese woman to graduate with a PhD in economics. Her doctoral dissertation, titled "The Economic History of China, with Special Reference to Agriculture" can still be found for sale online. Lee had always planned to return to China after her schooling. Highly educated women had difficulty finding appropriate work in the United States, and that was especially true for Chinese women. In China, Lee could have started a school for girls, and could have helped build China after the 1911 revolution. However, in 1924, Lee's father died and she remained in New York, taking over his role as director of the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City.

In memory of her father, Lee raised funds from the American Baptist Home Mission Society, and local Chinese American organizations to fund a Chinese Christian Center. In 1926, she purchased the building at 21 Pell Street in Chinatown. In 1954, she was finally able to secure the title for that building, solely under the First Chinese Baptist Church, which became independent of the American Baptist Home Mission Society at that point. The church became the first self supporting Chinese church in America, and still operates at 21 Pell Street. The Chinese Christian Center became a community hub within Chinatown, offering English classes and other skill building activities, a medical clinic and even a kindergarten were Lee taught. Mabel Lee never married, and she was able to maintain economic independence, in part because of her education. She died in 1966 at the age of 70. Although Lee is not as well known as other suffragists of the time, she was recognized in 2018 when the US Congress passed a bill introduced by Representative Nydia Velazquez to rename the Chinatown Station US Post Office at 6 Doyers Street in Mabel Lee's honor.

To help us understand more, I'm joined now by Dr. Kathleen Cahill, Associate Professor of History at Penn State, and author of the 2020 book, "Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement."

Hi, Kathleen. It is wonderful to finally meet you face to face, virtually. And thank you for joining me.

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 7:34

Absolutely. It is a delight to be here. I really enjoy your podcast.

Kelly Therese Pollock 7:38

Thank you. So I want to start just by asking, first how you got the idea of writing a book about women of color in the suffrage movement, and then more specifically, how you got interested in writing about Mabel Lee.

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 7:52

Yeah, absolutely. I had sort of two ways that I came to this project. The first was realizing that the anniversary of the 19th Amendment, the centennial was coming up, and sort of thinking about what those conversations would look like, and assuming that they would primarily be focused on white women and the East Coast. And as someone who studies Western history, and who was living in New Mexico at the time and thinking about sort of the variety of women's experiences, I wanted to think about how I could include some of you know, stories that might look really different from our regular suffrage stories in that conversation about the anniversary. One of the reasons I came up with that is because I had come across a woman named Marie Bottineau Baldwin, who was a member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Nation of Ojibwe and French heritage, and she had marched in the 1913 suffrage parade. And I had learned about her through my first book, which was an exploration of women who'd worked for the federal Indian Service, what becomes the Bureau of Indian Affairs. And so kind of taking that earlier research and thinking about contributing to the anniversary conversations, I thought, "Well, I'll write an article about Marie Bottineau Baldwin." And as these things are wont to do, right, it's sort of snowballed into a much bigger project. And the way I came to Mabel Lee was, I thought, "Well, let's think about that 1913 parade and some of the women of color who were involved in it." So starting with Marie Baldwin, and thinking about Indigenous women, and then I knew that African American women were there because of the work that had been done particularly on Ida B. Wells by other scholars. And so I was sort of looking for well, who who else might have been there? And this is we can talk later about the digitization of newspapers. But there was one Chinese woman who identified as Mrs. Wu who was in that parade on one of the floats. And in the process of trying to find out more about her and kind of Chinese women who were involved, I stumbled across Mabel Lee's story, because the year before the DC parade, which was 1913, in 1912, there is a major parade in New York City. And Mabel Lee is really one of the centerpieces of press coverage about that parade. So it she really was the reason that I even moved beyond kind of the 1913 parade and the project really expanded.

Kelly Therese Pollock 10:24

Yeah. And so she's in these, these newspaper stories about 1912, when she's only 16 years old. So we've got those sources, but we actually have a lot of material about her, a lot of sources to look through. Can you talk some about what what those are the kinds of ways that you were able to learn about her life?

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 10:45

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, the great thing about the newspapers was it allowed me to sort of find some of these women, because they are in the papers, and they're named and I can kind of follow up on on that. But then expanding beyond that, you know, I started looking at well, where might Mabel Lee have been having other kinds of conversations. So the Chinese Student Association, which was a college organization of Chinese students in the United States, had a journal, the Chinese Students Monthly, that luckily, I was able to access. At the time, I was at Princeton, and they had it in a database. So I could go through that and find, you know, she wrote three articles for them, specific ones, but very specifically about feminism and suffrage, the others constantly touching on sort of the issue of women's rights. But she's also kind of all over the reports that were also in that journal. And so learning about what she was doing in that organization helped me think about how her suffrage activism wasn't just confined to again, the kind of traditional national American Women's Suffrage Association that we often think of, but was in these other community spaces. And then because she is a Chinese immigrant, I knew that there were immigration files, and I knew that she had gone back to China. So, trying to find trying to track those down, and I was able to find the file for her first trip, which I believe was 1923. So when she leaves the United States, because she is not a citizen, and because she is Chinese, she has to request permission to come back in which was not necessarily guaranteed. So the file is very thick, right, where she has to get sort of non Chinese people to affirm she is who she is, she has to prove that she has been a student. I actually love she's a little sassy, I think and she is, she by this point has a PhD, right. So she has a degree from Barnard College as an undergraduate, she has a degree from Teachers College at Columbia. And then she has a PhD, and she literally sends them her 621 page dissertation to prove that she has been studying, right? She goes to China a second time in 1929 and I, that file seems to be missing. I've tried to find it in Seattle and San Francisco, and they can't track it down. So and then, um, her the first Chinese Baptist Church that her father founded, and that she ran for many years still exists. And another scholar had written an article about her and he connected me with Pastor Bayer Lee, who's who's not related to Mabel. And so they have, that community has been really generous with me. And in fact, as I mentioned, I'm going to speak there tomorrow. They're holding another anniversary celebration for her, the 100th anniversary of her PhD, which was in 1921. So they've been very generous in talking to me and sharing sources. And, again, they really have kept her memory alive. So all of those, right, once I was able to find her name, kind of following up in all of these other places really opened up her story.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:20

Yeah, I think what's so perhaps not surprising, but I feel surprising is that we don't know her better. Right? You know, so and this is the thing I think a lot about on this podcast in general is why don't we know these stories better? Why aren't these things something that we hear more about? And sometimes, of course, the answer is we don't have sources but here obviously, the sources are there. They could have been found and there's the First Baptist Church that continues to, to think about her and to celebrate her. So there's no as far as I can tell a full length biography of her. I looked around for videos about her and they'll be like a little one minute video and you know, like all these one minute videos, all repeat the same stories over and over again. So why do you think this really important figure, someone who is Chinese American and a woman and gets a PhD from Columbia, in 1921 in economics, I mean, this is like a big story. She's the head of this suffrage parade. You know, why, why has her story been, you know, except in the small pockets, not more widely thought about, widely talked about?

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 15:23

Yeah, I mean, that's the the, what is it, $64,000 Question? Um, it's a really good question, and I the, the answer I've come up with is her story didn't fit. Right. It didn't kind of fit into our narratives. For a lot of the women I write about, they're talked about as activists, but not necessarily suffragists. And then their activism is often in kind of more recognizable places. So, you know, Gertrude Bonnin, or Zitkala-Sa, who's who you've talked about in your podcast, you know, she's very well known as a leader in the Society of American Indians, or as an author. And Mabel Lee certainly wrote some things but didn't publish any books. And the people that she was writing for were really this Chinese student audience, many of whom went back to China, right? They couldn't naturalize in the US. And then kind of an international audience of business people and missionaries. So it really, and really, the Chinese suffragists, even those in the US are often at the time were positioned as foreign. Right, they were Chinese, they were part of the Chinese movement. And that has a lot to do with the US citizenship laws that, that were keeping them from becoming citizens, but also in the way that they were being othered. And so I think her story kind of falls into that. And so she didn't get remembered as a suffragist. She also, you know, really does most of her work in the Chinese community in Chinatown, and mainstream US narratives of US history are still not great about incorporating kind of those. There, again, the Chinese were seen as kind of outsiders and others and not really part of the central story. So I think that's, that's a big part of it. And, you know, there's a whole, there's a whole kind of story about what happens after 1920 that I think we are just beginning to uncover. I think the anniversary really revived a lot of these questions. But when I look at, you know, she's at Columbia, she's getting a PhD, there are other women, that getting PhDs. And the numbers of women getting PhDs are actually rising in the early 20th century, but they run into this problem of there are no jobs for them. People refuse to hire women as professors, and especially a Chinese woman in the US. And so the numbers then begin to drop, right, so for so after the 20s, I think it is, the 30s, 40s, and 50s, the numbers of women getting their PhDs really dropped. And so we kind of assume that women weren't getting right, that it wasn't until the 60s or 70s. So I think part of it is also just that context and story that we tell ourselves about women's history. And there is really, we think of history as like, always positive and always progressing. And I think this is a really good example of, you know, women made a lot of strides in the early 20th century that then and then there was some resistance and loss of those gains, that had to be re- fought in the 60s and 70s. And so you know, the way we tell historical narratives can create these places where people get overlooked, either because we assume well, women didn't start doing this until later, or well, who was a suffragist? Mabel Lee didn't necessarily fit into that.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:08

Yeah. Do we know from her writings at all, or from the stories that people that knew her talk about, did she think of herself as American or Chinese? Was it not that that simple?

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 19:22

Well, she couldn't become a US citizen. And she does talk a lot about returning to China initially, and she talks about right China as her country. And, and she really does focus a lot of her women's rights advocacy on this Chinese Students Association, where most of those students are men, not all of them, but most of them. They are absolutely going back to become the leaders of the new Chinese Republic. And so she is part of building that new nation and she's very involved in these trans- Pacific conversations. She ultimately doesn't go back, and I think there are a couple of reasons. One, you know, kind of the rising tensions between China and Japan, and the violence there that that ultimately it starts before World War II broadly. But then also when her father dies, she's sort of torn between, you know, does she take over his life's work, which is the the First Chinese Baptist Church that he has founded? Or does she sort of move into, she was sort of thinking about international business. And she had thought about going back to China. And she ultimately decides to, to work with the church. And she raises money to build a five storey building in Chinatown in his honor, where the church still exists and serves as a community center. And, you know, he had really supported her, in some ways, very unusual for a Chinese girl to be educated as highly as she was both in kind of the Chinese classics and those traditions which he was working with her on, and you know, in the US system, where she, again goes to college, and he was a big supporter of that along with her mother. So she has this and she talks about filial piety and one of her articles and felt very strongly about that. So, you know, I think she, she did consider herself Chinese and was excited about the new nation, and, and felt very much a part of building that. But ultimately does choose to stay in the US.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:37

So I guess maybe that starts to answer this question is, you know, why, why is she working in in suffrage and women's suffrage when she is not going to get to vote? So you know, women in New York state get the vote, and then, you know, across the country in 1920, and but she doesn't. She's can't vote until 1943. And as far as I can tell, we don't know if she ever did end up voting. But is that because she's thinking more broadly than just America and her own ability to vote?

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 22:08

I think she's thinking more broadly in two ways. Both she is thinking in terms of these international and transnational conversations about women's rights, right? This was a global movement. It wasn't just happening in the US. Carrie Chapman Catt is initially before she's president of the National American Women's Suffrage Association, she's president of the International Alliance Women's Suffrage ( I can't remember the full title.) But so so conversations are happening in China around questions of modernization, and ultimately, what becomes the Republican revolution in 1911, that overthrows the Qing Dynasty, and is talking about right, ending the Empire and establishing sort of democratic systems of governance and how women's rights are part of that conversation. Dr. Sun Yat Sen and the revolutionaries are supportive of women's rights. And initially, it seems as though women will get suffrage in China. So she's part of those international conversations, as are you know, her mother and some of the other women in New York City's Chinatown. But she's also and this is true for many of the women I write about. They see suffragists, white suffragists and suffrage conversations as a way into a much larger conversation about citizenship and rights, that their communities that they really want to advocate for. Right. So she, when she gives her speech at 16, to these prayed that the biggest suffrage leaders in the nation, Anna Howard Shaw, for example, who's president of NASA, she's talking about women's education and how Chinese students, boys and girls are sort of shut out of educational opportunities. And she talks about right what we would call intersectionality. And how being Chinese and the sort of limitations on on citizenship for Chinese immigrants are affecting Chinese women and, and white American women should be caring about this topic and should be sort of helping. So she's really navigating kind of these multiple conversations. And suffrage is a place where, women's suffrage is a place where enormous numbers of women are active. They're having these conversations about citizenship and rights. And it dovetails really nicely with again, women of color who want to talk about rights and gender and how their experience is different from white women, but equally valid.

Kelly Therese Pollock 24:48

Yeah, so I want to talk some then about her time in the ministry, taking over after her father dies. Would this have been unusual at all for a woman to take charge of this congregation? It you know, it seems like it's, it's just sort of accepted. Okay, she, you know, it was her dad's ministry and now it's hers, you know, and you know, as she's raising money for a building, you know, and and all these activities as, as a woman in this was like 1920s. Like it seems unusual not just for a Chinese woman, but for a woman at all in this time. So can you talk some about that and the the sort of the the way that this congregation then accepts her and seems, at least in hindsight, 100 years later, seems to have really welcomed her.

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 25:39

Yeah, that's a great question. And I will say that the scholar who introduced me to the church, Dr. Timothy Tseng, has written a little bit about this. So I'm going to draw on his work. But yeah, I mean, she, I think, as someone who was very well educated, right, she has a PhD, she is her father and mother's only child, she's an only child. So in some way, she's sort of a natural heir to this position. But also, she's part of a generation that's coming out of the settlement house movement, right. And so women like Jane Addams in Chicago, or Lavinia Dock and the Henry Street settlement in New York. But there's that as a precedent. And at the First Chinese Baptist Church, they're largely helping Chinese immigrants, and and the community. And they're doing things like there's there are kindergarten classes and kind of language classes. And so the church work is also part of that kind of settlement house work. And there is a precedent for women in those positions. And actually, her very good friend, who, she who was a Chinese intellectual, he'd been a student at Harvard, he's an editor in China. And he, he says to her, right, "Weren't your ambitions to be the Chinese Jane Addams?" And so I think that model was there. I think the the Baptist Church appreciated, I mean, she has these incredible skills, I think she was very good at it. Ultimately, there's a lot of tension there. And she spends quite a bit of kind of the 30s and 40s and 50s, trying to get control of the church, from the Missionary Society. And I imagine as a woman with a PhD, it was really frustrating that she couldn't make a lot of the decisions on her own. And so she never becomes the minister. Right. So in that sense, it's she's not quite the same as her father, but she's administering it. And she does have a board of deacons, and men who are helping her run the church. And, and a lot of the pictures from this period are right, she's the only woman kind of in the group of men, which is interesting. But I have less from her in terms of sources writing about that. So I don't know for sure. But I do think initially, she really, that settlement house model worked for her. And there were, again, sort of these moments in women's history, right? Women missionaries, who the sense was, I mean, especially in terms of proselytizing to other women, you needed female missionaries. So there are in that early, you know, kind of late 19th, early 20th century, these other models of the missionary model, kind of the settlement house model where women were, had more, I don't want to say power, but had more ability to kind of be in charge of some of these organizations.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:39

Yeah. So at the end of your book, which everyone should go read, by the way, it's very readable, in addition to being a wealth of information, but you talk about these women, the women of color, not just Mabel Lee, but all of the women that you write about thinking about history and their place in history and how we construct history, you know, sort of where we started this conversation. So can you talk some about that broadly, not just for Mabel Lee, perhaps but you know, what, what they were doing in a way to make sure they were sort of writing themselves into the story?

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 29:17

Yeah, absolutely. Well, let me start with Mabel, and then kind of open it out. So for her, she's really thinking about tradition, and breaking tradition, because of the Chinese revolution, right. And the language of those revolutionaries is right, in part, it was a response to these sort of Western stereotypes about China as backwards and caught in traditions so much so that that again, Chinese, they're seen as so different from the Western world. And this is part of the reasoning behind the US enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Act and not allowing Chinese immigrants to naturalize. I mean, that's unusual. There's no other group of immigrants that the US treats like this. It has everything to do with the sort of stereotypes of China and the Orient, right, quote, unquote Orient. So the revolutionary that she is, and sort of this younger generation that she's engaged with, they're all thinking about, you know, overthrowing tradition and starting something new. And in her dissertation, which is an economic history of China's agriculture, and she looks at like two centuries of agricultural history, she's arguing, you know, we can't throw everything out, we actually should look, she says, at older sources, with new scientific methods and sort of learn from that past to help the future. So she's really thinking about these kinds of questions broadly because of that. And she's also right, as she's engaging, with white suffragists, really educating them about what's happening in China, and trying to pull them out of their very ethnocentric notions of suffrage and saying, well, here's what women in China are doing, and the women's rights movement in China. And you know, let's think about these things together. The other women that I write about are also really thinking about history, in large part because they recognize that in the United States, these claims to belonging are often very steeped in history. For African American women, this is the moment where the Civil War is being rewritten, right? And white Southerners, the Daughters of the Confederacy, are really rewriting the Civil War into the kind of honorable fight between brothers, that slavery, you know, maybe shouldn't have been overturned, and rewriting, you know, what emancipation meant, that it was actually bad for African Americans. And Black women are responding to that by offering an alternative history of "No, actually, right. Slavery was bad. Women were sexually assaulted all of the time, right? Families were torn apart." And so trying to counter those narratives that were really seductive. And I should say, it's not all white Southerners. Professor Dunning at Columbia was one of Mabel's, she's there at the same time, Mabel Lee is there is also participating in this. Woodrow Wilson is participating in that retelling. So, you know, this is a moment that early 20th, late 19th, early 20th is very similar to our discussions today, right? For me, I see in the discussions about the 1619 Project, very similar stances, right, where there are a group of people who don't, who reject kind of what the 1619 Project is saying, because it undermines claims about sort of the progressive history, right, that history is always getting better. And that the the people writing in the 1619 Project are saying, but actually, you know, "Let's confront this past." So history is always political. And it was for these women as well. And again, that that turn of the century, along with the rewriting of the Civil War, there's also a real interest in the revolution. And this is Laurel Thatcher Ulrich's "The Age of Homespun," where, you know, there's a real kind of fascination with that American Revolution and American identity. And so women like Nina Otero-Warren and other women of Hispanic descent, and they choose Hispanic very deliberately, as opposed to Mexican descent in the southwest, in California and New Mexico. They're making claims, they're talking about their community's history as conquerors of Native people, as a way to claim US citizenship, right? Well, yes. Just like, you know, the people on the East Coast, the British on the East Coast, conquered Native people. And that's what made them Americans, right. This is, this is the moment of the frontier thesis,you know, Hispanic, our Spanish ancestors. And they kind of ignore that their, their ancestry is both Spanish and Indigenous. They were also sort of conquering from the south. And so they're using that to claim an American identity. So the way in which history is used to claim identity as a member of the United States. A lot of these women are doing that. And part of that is to say, here's how our community contributed to the creation of the US and in Mabel's case it's less that and more, here's how we're contributing to sort of women's rights as a as an international conversation.

Kelly Therese Pollock 34:45

Yeah, yeah. It's so interesting reading those sort of seeing how these women are navigating, being not white in different ways and how they are received differently by white society and you know, it's really fascinating to sort of, you know, sort of thread that through. And so that that I think, is one of the really interesting parts of the story is, you know, it's women of color. But of course, these are all very different. They're experiencing it differently. They're experiencing being in America differently. And in doing what they have to do to sort of get get the rights that that they would like to get.

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 35:26

And that was actually a really kind of a tough coming up with a term. And I don't love women of color, right? Because it does lump every, you know, all of these women into a category that is not right. And what I hope is, by the end of the book, people will realize that they're coming from different places with different motivations. There are places where those things overlap, and they overlap with white women in some places as well. But we can't just say that there was one kind of women's experience, that we have to think intersectionally that we have to think about the communities they're in, the places they're in, right. Suffrage, in particular is a real state by state narrative. And that does matter. You know, Black women in the South have a different experience from Black women in the north or the West. So yeah, I do hope that that even though I use women of color in the title by the end of the book, people might think well, that's, that's too, the term doesn't, it's too flattening.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:30

Yeah. Yeah, no, definitely. And you mentioned Woodrow Wilson a bit ago. So let's just say he does not come off very well.

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 36:38

He does not, you know, and yeah, exactly. I and I knew, again, I had been at Princeton for a year, I was on sabbatical. And it was during the sort of, when the students were were when the students were protesting the name of the school and sitting in in the president's office. And I sort of knew that, and I knew Wilson was bad, but it really was writing this when, and sort of seeing exactly those moments when he is segregating the civil service and what that meant, it was extremely disappointing, but also just really revealing. And, and as I said, I sort of knew that, but to really see it affect the women I was writing about was powerful. And, and that led me to write kind of one of the moments when you're writing about individuals, you often become, you know, you feel like you know, them, enjoying writing about them. And and that was one of the early moments when Marie Bottineau Baldwin, who is a Native woman working in the Civil Service in Washington, DC in 1913, where I found a letter from her attacking a Black doctor, who was also an employee in this in the Civil Service. And using this really racist, white supremacist language about Black men shouldn't be with, you know, young Indian girls. And we all know how that they are. And to sort of take that and say, "Well, what do I do with this right? Here is a woman who, you know, is also from an oppressed group, right as a Native woman, and is very politically active both in the Society of American Indians and in the suffrage movement, and here she is attacking a Black man. What do I do with that?" And that's where I really had to start thinking about well, just because people are from oppressed groups doesn't mean they don't also participate in oppression. And that helped me think about, again, how a Native woman could use white supremacist language to talk about a Black man. It made me think about how women like Hispanics or Latinas, like Nina Otero-Warren could be talking in very patronistic ways, and using a language of of colonization and imperialism to talk about Native people. And how these were parts of their political strategies, um, that we have to think about as well.

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:06

I just want to bring up the the sort of what would feel to me like the most shocking is probably not the right word, because if I'd really stopped and thought about it, I think I would have realized that this moment would happen. But it's right after the 19th Amendment is finally ratified. Women are voting for the first time in the 1920 election, African American women in the south are not able to register to vote or show up and have been struck from the rolls. And they go to Alice Paul for help. And she basically is just like, "Can't help you. It'll make too many white women mad." And so I don't know, maybe if you could just talk about that. That moment and that tension, and you know, what, maybe what they can tell us about sort of today and the importance of white women being allies for women of color.

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 39:57

Yeah, one of the thing and one of the things that I want the book to do is to make us really think about 1920. And, and here I am not original right. Here, I'm absolutely learning from feminist scholars of color, and especially African American scholars of African American women's history that, you know, just because this 19th Amendment passed doesn't mean that all women suddenly started voting. And, you know, when I looked at these individual women, you could see that 1920 isn't necessarily the endpoint for a lot of these women's fight for the right to vote. And it's because it says, right, "The vote shall not be denied on the basis of sex." But that leaves a lot of other ways in which it can be denied. And so you see this with the women that I'm writing about that some of them, Nina Otero-Warren, as a woman whose citizenship and whiteness is guaranteed by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, is able to vote and even run for Congress in 1922. Native women are still not considered US citizens in 1920. They have to keep fighting. We see Black women in the South keep fighting. Mabel Lee is again, also not a citizen, and Chinese immigrants are not going to fall under that naturalization of the 14th Amendment until 1943, and then 1950, I think it's the 1954 loss. So those narratives, keep the fight head keeps going for those women. And you're absolutely right, they go to white women who now can vote and ask for help. And we see this Gertrude Bonnin, or Zitkala-Sa really does this. She asks Alice Paul, and these Black women are also asking Alice Paul, and this major conference right after that 19th Amendment and Alice Paul is sort of like, well, you know, what kind of, she sort of says, "We'll take care of it at some point," but she's not interested in focusing on that. And she eventually will say, well, the equal rights amendment will, will take care of it. And that's her focus, but she's clearly not met her she sees the fight for the right to vote as over. And it's not. And these women have told her that it's not, right. They've told her their experiences. Other women's groups, white women's groups are more willing to ally in other places. The NAACP is biracial, the General Federation of Women's Clubs really takes up the question of Native women's right to vote, but it is not all white women's groups do. Right. And that's where we see for sure, you know, some disappointment in terms of allyship. So I don't I get, I do get asked that a lot. Like, what does this mean for the present? And I, I mean, I think, I don't always feel like I have a good answer to it. It is disappointing, right? It was really disappointing. And it does make me at least stop and think about how I'm approaching issues, who I'm listening to. As I said, a lot of these women were trying to educate their white audiences, and they were not always getting through. And so I really do try to myself make sure that I'm listening to women of color and asking, "What are they suggesting?" Because and again, Black women in particular, were often saying, you know, "If we who are really, right, the most, you know, oppressed group of people, and with this intersection of race, and, and sex, if we have our rights, then everybody will have their rights." And I think that's a really powerful position to keep in mind. And I think they were absolutely right. And they've been saying that for many, many, many decades. So.

Kelly Therese Pollock 43:51

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 43:53

I think what most surprised me in finding her story was just how much people were talking about Chinese women and Chinese women's right to vote. And you know, there's a good year and a half where that's a really dominant theme in US suffrage organizations. Again, Anna Howard Shaw, who's the president of the national organization, spends an entire summer carrying this banner that she had carried in that 1912 parade that says "NASA Catching Up with China." Her whole speaking tour, from the parade in May, through the summer to the Democratic Convention in August, is about China and Chinese women's right to vote which the US sort of thinks is happening. It's more complicated. And so that, you know, the fact that it was that visible at the time, and then completely got forgotten, really fascinated me sort of thinking about how did that happen? And what was going on, right? I always tell my students if you find something in the sources that you don't understand and you think, "What's up with that?" you've got to follow that. And I'm so glad that I followed this question of, you know, what is Mabel Lee doing it the head of this parade. That didn't make any sense to me in terms of how the suffrage story that I had been taught and suffrage narrative I had been taught. And so there it there was.

Kelly Therese Pollock 45:23

Well, I'm glad you followed it up too. And I'm glad I got to learn about Mabel Lee. So Kathleen, thank you so much for joining me. This was a terrific conversation. And I'm so glad that I got to learn more about Mabel Lee and and all of the women that you write about.

Dr. Kathleen Cahill 45:38

Thank you. This was so much fun. I really appreciate it.

Teddy 45:41

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode at UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History. Or on Facebook at Unsung History Podcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Cathleen Cahill

Cathleen D. Cahill is a social historian who explores the everyday experiences of ordinary people, primarily women. She focuses on women’s working and political lives, asking how identities such as race, nationality, class, and age have shaped them. She is also interested in the connections generated by women’s movements for work, play, and politics, and how mapping those movements reveal women in surprising and unexpected places. She is the author of Federal Fathers and Mothers: A Social History of the United States Indian Service, 1869–1932 (University of North Carolina Press, 2011), which won the Labriola Center American Indian National Book Award and was a finalist for the David J. Weber and Bill Clements Book Prize. She is currently engaged in two book projects. Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement (forthcoming Fall 2020) follows the lead of feminist scholars of color calling for alternative “genealogies of feminism.” It is a collective biography of six suffragists–Yankton Dakota Sioux author and activist Gertrude Bonnin (Zitkala-Ša); Wisconsin Oneida writer Laura Cornelius Kellogg; Turtle Mountain Chippewa and French lawyer Marie Bottineau Baldwin; African American poet and clubwoman Carrie Williams Clifford; Mabel Ping Hau Lee, the first Chinese woman in the United States to earn her PhD ; and New Mexican Hispana politician and writer Nina Otero Warren–both before and after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Her next project, Indians on the Road: Gender, Race, and Regional Identity reimagines the West Coast through … Read More