The Jazz Maestros of Jim Crow America

Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie came of age in a deeply segregated country, battling racism to become celebrated musicians, composers, and band leaders whose music lives on. Joining me this week to discuss the lives and careers of these three musical geniuses is writer and journalist Larry Tye, author of The Jazzmen: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie Transformed America.

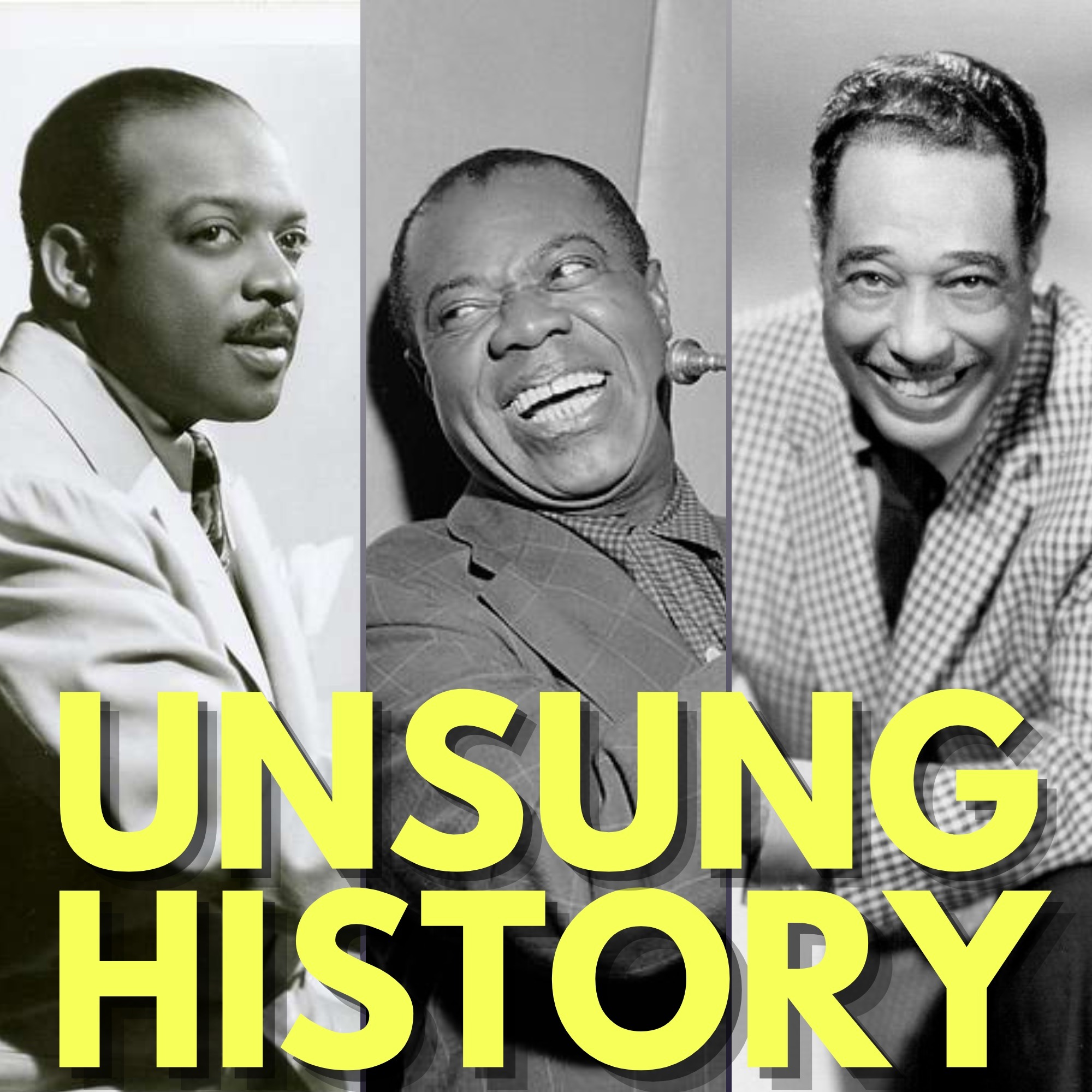

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “Riverside Blues,” performed by King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band in 1923; the song is in the public domain and available via the Internet Archive. The episode images are: “Count Basie,” taken by James J. Kriegsmann in 1955, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons; “Louis Armonstrong,” Herbert Behrens / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons; and “Duke Ellington,’’ Associated Booking (management), 1964, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Additional Sources:

- “MLK Jr. on Jazz, The Soundtrack of Civil Rights,” by Mark Taylor, San Francisco Conservatory of Music, January 14, 2022.

- “Duke Ellington, a Master of Music, Dies at 75,” by John S. Wilson, The New York Times, May 25, 1974.

- “Seven facts to learn about Duke Ellington,” by Cristiana Lombardo, PBS American Masters, July 18, 2022.

- “Duke Ellington,” Songwriters Hall of Fame.

- “Louis Armstrong, Jazz Trumpeter and Singer, Dies,” by Albin Krebs, The New York Times, July 7, 1971.

- “Louis Armstrong Biography,” Louis Armstrong House Museum.

- “9 Things You May Not Know About Louis Armstrong,” by Evan Andrews, History.com, Originally published August 4, 2016 and updated June 1, 2023.

- “Count Basie, 79, Band Leader and Master of Swing, Dead,” by John S. Wilson, The New York TImes, April 27, 1984.

- “Count Basie Biography,” Rutgers University.

- “William ‘Count’ Basie,” National Endowment for the Arts.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

In 1964, at the first Berlin Jazz Fest, Martin Luther King Jr. said this of jazz, "Much of the power of our freedom movement in the United States has come from this music. It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down. And now, jazz is exported to the world, for in the particular struggle of the Negro in America, there is something akin to the universal struggle of modern man. Everybody has the blues. Everybody longs for meaning. Everybody needs to love and be loved. Everybody needs to clap hands and be happy. Everybody longs for faith. In music, especially this broad category called jazz, there is a stepping stone towards all of these." In this episode, we're looking at the lives of three of the biggest jazz musicians and band leaders of the 20th century, who succeeded despite the challenges of being Black musicians in Jim Crow America, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie. Edward Kennedy Ellington was born on April 29,1899, in Washington DC, then a city of over a quarter million people, around a third of whom were African American. Both of Ellington's parents played piano, and he began piano lessons at age seven, although he was more interested in baseball at the time, and he had an early job selling peanuts at Washington Senators baseball games. From an early age, Ellington's friends called him Duke because of his regal bearing. Inspired by the Ragtime pianists he heard at Frank Holiday's Poolroom, Ellington started taking piano more seriously. He composed his first piece at the age of 15, "Soda Fountain Rag," while working as a soda jerk at the Poodle Dog Cafe in DC, near Howard University. A skilled artist, Ellington won an art scholarship to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, which he turned down to stay in DC. He worked as a freelance sign painter, while also performing. When a client would request a sign for a dance or party, Ellington would ask if they needed musical entertainment, booking gigs for his band that way. Ellington followed drummer Sonny Greer to New York, and in 1927, the Duke Ellington Orchestra began a four year run at the Cotton Club in Harlem, bringing him national attention. Ellington wrote or collaborated on over 1000 musical compositions, and he won 14 Grammys, three of those posthumously. Ellington married once, to Edna, and they had one child, a son named Mercer Kennedy Ellington. However, Ellington also had several long term mistresses whom he never married. On May 24, 1974, Edward Duke Ellington died of pneumonia, a complication from lung cancer, in New York City. He was 75 years old. Louis Armstrong was born in New Orleans, likely on August 4, 1901, although his birth date is debated, and Armstrong himself sometimes claimed he was born on July 4, 1900. Armstrong's father abandoned the family when Louis was little, and he was raised in poverty by his mother and his grandparents. In 1912, Armstrong was arrested and sentenced to the Colored Waifs Home for Boys, where he lived for 18 months. While there, he played cornet in a band, and further developed his musical skills, which he'd learned on the street. In August, 1922, his mentor, band leader Joe "King" Oliver, invited him to come play with his orchestra in Chicago, which launched Armstrong's career. Armstrong's aggressive style of trumpet playing was rough on his lips, and he suffered from scar tissue and lip ulcers through most of his career. He self medicated, becoming at one point an official spokesperson for Ansatz-Creme Lip Salve. In part because of how painful the trumpet was, Armstrong increasingly turned to vocals, incorporating scat singing into his performances. Armstrong composed over 50 songs, had 19 Top 10 records, and won a Grammy in 1965 for male vocal performance for "Hello Dolly," the recording of which knocked the Beatles off the number one position on the Hot 100 chart, and which remained in the top 100 for 22 weeks. Armstrong regularly collaborated with other jazz artists of the day, including recording three albums with Ella Fitzgerald, "Ella and Louis" in 1956, "Ella and Louis Again" in 1957, and "Porgy and Bess" in 1959. Armstrong married four times, staying with his last wife, singer Lucille Wilson, from 1942 until his death. None of the marriages produced children, but he secretly supported a child he believed he had fathered in an affair, sending monthly checks to her and her mother for over 15 years. On July 6,1961, Louis "Satchmo" Armstrong died of a heart attack at home in Queens, New York City. William Basie, was born on August 21, 1904, in Red Bank, New Jersey. Basie's father was a coachman, and then after automobiles replaced horse drawn carriages, he became a groundskeeper. His mother was a laundress. As a child, Basie did odd jobs in the theater in exchange for free admission to shows. He was the best student in his class and a natural at the piano, though he preferred drums. Before he was even 20 years old, Basie was touring around the country as a solo pianist, and as an accompanist for vaudeville acts. When one of his touring groups disbanded, he was stranded in Kansas City, and he stayed there, playing first with Bennie Moten's band, and then with his own nine piece band, The Barons of Rhythm. It was during a live radio broadcast at the Reno Club with the Barons of Rhythm that a radio announcer gave him the nickname, "The Count." Basie's composition, "One O'clock Jump" from 1937, was the signature piece for his orchestra and became such a popular jazz standard than in 2005, The National Recording Preservation Board included it in the Library of Congress National Recording Registry. Basie recorded over 480 albums over a 50 year career, and won nine Grammy Awards, becoming the first African American to win a Grammy in 1958, for his album, "The Atomic Mr. Basie." Basie was married twice, briefly to Vivian, and then for decades to Catherine, with whom he had his only child, a daughter named Diane,who was born with cerebral palsy. Bill and Catherine chose to raise Diane at home, even when others recommended institutionalization.

On April 26, 1984, William "Count" Basie died of pancreatic cancer in Hollywood, Florida. He was 79 years old. Joining me now to help us understand more about the lives of these fantastic musicians is writer and journalist Larry Tye, author of "The Jazzmen: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie Transformed America." First though, here's "Riverside Blues," played by King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, in 1923. You can hear a young Louis Armstrong on cornet and his soon to be wife, Lil on piano.

Hi, Larry, thanks so much for joining me today.

Larry Tye 12:08

Great to be with you, Kelly.

Kelly 12:09

Yes. I am thrilled to be talking about these three incredible jazzmen. So I want to start by asking what got you interested in writing the story?

Larry Tye 12:21

So I'll tell you that. But I want to say if your toes aren't tapping by the end of our interview, then I've failed and more importantly, three maestros, who more than any three people in America over a whole half century, got America's toes tapping. And what interested me was I did a previous book on the Black men who worked on George Pullman's railroad sleeping cars, and they were known as Pullman porters. And they were an extraordinary group. And they were hired by George Pullman, because many of them in the early days were ex slaves. And they ended up I think, giving birth to today's Black middle class, a professional class. And when I interviewed the Pullman porters, they made me promise that I would someday write two books when I got done writing about them. One was about an amazing baseball player who may have been the fastest and most talented pitcher ever to pick up a baseball, and his name was Satchel Paige, and as promised, I wrote a biography of Satchel Paige several years ago, and the three favorite passengers of my Pullman porter interviewees were three guys named Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie. So I wrote about them partly because I promised the Pullman porters, and I would never go back on my word to those Pullman porters, but also because, as the porters helped point out, I thought these three guys did something that was never part of the written legacy, or the previous biographies of what they did. There are a million smarter people than me who understand music much better than me, who've written about what these guys did on their bandstand. But I thought their life off the bandstand was maybe more compelling, and was an even longer lasting legacy. And that is in simple terms, that these Pullman porters wrote what I think of as the soundtrack for the civil rights revolution in America. And you can't do anything better than that.

So I want to hear a little bit about the research you did because it seems massive amount of research went into this book. You talk about the number of people that you interviewed, pages and pages of notes you have. So could you talk a little bit about how you went about doing this and keeping the stories of three separate, interrelated but separate, people straight?

Great. So those are two great questions. And I'll answer the first one first, which is the research that I did. And the only common theme in the nine books that I've written is, I get to people late enough that the first reply I get from everybody I talked to is, "You should have been here 20 years ago, when more of their family and friends and bandmates were alive." And as with the eight previous books, who were on subjects that which were on subjects ranging from Bobby Kennedy, to Senator Joe McCarthy, as in those books, I found that once I got to one family member, they would point me to three or four others. And once I got to one bandmate, they would tell me, "Oh, well, all of these people are alive, and you just have to get to them in their nursing home and get to them tomorrow." And the biggest challenge was, I naively thought that when you were writing a biography of three people, you would only have to do a third of the work that you would in a normal biography, and at the end, you'd end up at 100%, the same amount of work. It is not true. And for any of your listeners who were ever contemplating putting more than one character into a book, you multiply the research you have to do by the number of people you're writing on, meaning, even though only a third of my book was about Duke Ellington, I had to do the research, as if I were writing an entire biography of him. And what that meant was, the thing that I trust most in any of these things, is not getting accounts secondhand, either from journalists, or from previous biographers, but by getting it firsthand from people who knew them. And so let's just take Duke Ellington. What I did was I talked to his granddaughter, who was his closest living relative. And then I talked to his nephews. And then I talked to probably two dozen of his bandmates. And then I talked to everybody who knew intimately his story in a way that I could get a firsthand sense because they had known Duke. And then you go, and you do all the library research, you look at archive. And that means in Duke Ellington's case, the Smithsonian, it meant all the jazz museums around the country that had anything Duke Ellington related, it meant asking every government agency from the FBI to Washington, DC, where he was born, from their archives, divisions, every document that I could get on him in everything anybody had ever written over the years. And when you are as famous a musician as Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie, that means 10s of 1000s of papers. The good news is no three more fun people to be reading all that material about, and I had a blast. And I just now have to figure out what I do with the 250 books that I gathered in the course of writing this book, in order to make space for the next book I just signed up for. And what I hope to do is give back to them by auctioning off these books and the papers to collectors of materials of these three guys, and then giving it to one of my favorite sources of charity, which is public radio.

Did you find yourself at all getting their stories confused? Or were they such distinct personalities that it was easy to sort of remember who you were talking about at any given time?

So they were, for three guys who grew up in the same era, who lasted for the same 50 years at the top of the music heap in the jazz world, and who shared so much on first glance, they were extraordinarily distinct characters. Duke Ellington was an incredibly elegant and understated guy. If he could have picked one word to describe him, it would have been suave. And that is what Duke Ellington was. Louis Armstrong was an over the top guy whose heart was on his sleeve, whose soul was on the other sleeve and who just in everything he did, he was out there loving to ham it up and to be a life of whatever scene he was in at the time. And Count Basie was somewhere in between. He was as soft spoken as Duke. He was much more private than either Ellington or Armstrong, and he considered himself the consummate bandleader wanting the showmen in his band to take center stage and never wanting to do it himself. So, it was on the one hand, some overlap because of all ways that they overlapped. But it was never possible even for somebody has ham handed as I was at times, to mistake one for the other two.

Kelly 20:12

Can you talk a little bit about the the America that they are born into, that they're growing up in, what it's like for the three of them as African Americans in this time period, to be able to break through to become eventually the world famous musicians that they did?

Larry Tye 20:32

So in some, in some ways, they grew up in three entirely distinct worlds. And it's one of the things that was appealing to me about picking these three guys, other than that they were the naturals if you were looking at jazzmen who had influence at that time. Louis Armstrong grew up in an area in a very tough part of New Orleans at a moment when it was the ultimate representation of Jim Crow America, meaning that everything from the water fountain you used to which park you were allowed to go to, to which library you were admitted to, everything was defined by Jim Crow segregation laws, and everything for a Black man, like Louis Armstrong, was generally considered to be second rate. All of those institutions got much less funding than their white counterparts. And he was told no, repeatedly, just as a matter of course, when he was growing up in segregated New Orleans. Duke Ellington grew up in a place that had the largest Black community in America, which was Washington DC. And it was in a way, like a border territory. It had some of the worst of Jim Crow in terms of what he could or couldn't do. But it also had some of the relative and I definitely underline the word relative enlightenment that the north had, in approach, then approaching race relations at a time when the entire country was racist. The Count Basie's world was as north as you could get in terms of racial mores and standards and codes. And that meant that he had a whole lot more freedom in what he could do, than either Armstrong or Ellington, but not nearly what a human being should come to expect, and hopefully today can more come to expect in terms of the way his country treats him as a Black man. And Jim Crow is generally thought to be describing something that happened below the Mason Dixon Line in the southern states. But in fact, anywhere you went to in America back then, you were subjected to Jim Crow bigotry.

Kelly 22:47

So you mentioned that you talk to the Pullman porters, and that they encouraged you to write about these three. Could you talk about how travel is such an important thing to these three? They're on the road constantly through various parts of their life. And so what does travel look like for them? And why is it so important to them once they're able to to ride in the Pullman cars?

Larry Tye 23:12

So travel was important because especially when they were going south, that was where are they spent their time. They spent time, endless amounts of time, getting from place to place, much more time than they spent, actually on a bandstand doing what they came to do, which was to play great music. And getting there was an enormous challenge. Many of your listeners will have seen a movie about the Green Book, the famous book that told Blacks of that era, "Here's where it's safe to stay. Here's where it's safe to eat, when you're traveling in dicey segregated America." The truth is, that long before there was a Green Book, the Pullman porters and traveling jazzmen like these guys, knew from harsh experience where it was safe to stay, where it was safe to eat, and word was passed along. The porters told them, they told the porters, everybody exchanged experiences for one simple reason, which was the wrong choice, trying to go into a hotel that didn't allow Blacks there, trying to get served at a restaurant that didn't allow Blacks there, could end up putting you on a lynching noose. It was potentially a deadly experience. It was certainly guaranteed to be embarrassing as you were shown the door. But in lots of cases, people did more than show the door. They responded with violence. And what that meant was when these guys could finally afford to travel in a degree of luxury, what they did was hire Pullman sleeping cars, and they hired them because when you went south, and you were performing, let's say in Atlanta, if at night, if you knew you could, you had a safe hotel and dining room for you in the form of that Pullman sleeping car, which they rented and had pulled off on a sidetrack, it meant that you didn't have to hassle after you had done your great performance, with where could you safely be? And it meant that you had these extraordinarily elegant Pullman porters taking care, every whim that you had. Did you want your suit pressed? Did you want a meal in the middle of the night? Whatever you wanted, you got, because these were Pullman porters, who were trained to give that kind of service, and they adored Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie. So whatever their general level of high service was, it was three times higher for these three, and what these guys did in return for them, and I can only begin to imagine how magnificent this was, what they did was in their closed capsule of a sleeping car in the middle of the night, when these guys got back from the late night performance, they would give a private jam session for the Pullman porters who were taking care of them. So the acoustics must have been amazing. The idea of having Ellington, Armstrong, or Basie and their bands to yourself, must have been made you feel about as special as you can get. And it was a tit for tat that never had to be discussed in those terms of tit for tat, because just the porters knew what the bandsmen wanted in terms of being taken care of, and the maestros knew how to give back. And that was by performing.

Kelly 26:40

That's incredible to think about. So the subtitle of your book is about how they transformed America. And so I wonder if we could talk a little bit about that. They are not the sort of outspoken civil rights activists that you might find a generation later, but they are clearly at the forefront of changing people's views about what is possible, about where they can and can't go. Could you talk a little bit about that, and how each of the three approached that?

Larry Tye 27:10

First I would say, self consciously, and very intent, intentedly, if that's the word, these guys were trying to be low key. They knew that if they were taking on controversial issues, like trying to tear down Jim Crow, that it would make it more difficult for them to get bookings, and for their bandmates to make a living. And so what they did was, they did it quietly at the beginning, a little less quietly, as time went on, but they did it, I think most effectively as people who set the table for things that were going to come, like Brown versus Board of Education, the Supreme Court decision that desegregated America schools, the desegregation of baseball, so there no longer needed to be a Negro Leagues, the major leagues integrated long before any of that happened. These guys were out there, traveling across America, and their records were being offered across America, showing that their magnificent music, making the case without having to say it, that it could only be magnificent artists who could produce music like this, and showing Black brilliance and opening America's ears and souls, to the fact that Black men could entertain them in this way and could be artistic and define a new medium, like jazz was back then, just made a case in a way that trying to do it overtly would never have done. And so I would suggest to you that white racist men who would never have thought to let a Black cross their threshold, were wooing their sweethearts with the music of Louis Armstrong, and white women who would have walked to the other side of the street if they saw a Black man come down the street towards them, were listening every chance they got to the sweet sounds of Duke Ellington and Count Basie. And don't trust me, because I'm an old journalist and you never trust a journalist. Trust Martin Luther King Jr. who said in very little noticed speeches twice, he paid heed to these jazzmen, saying that they had made his work as the pioneer in civil rights so much easier by having shown the country just how magnificent these artists were. And I would like to say that if Martin Luther King opened the door to civil rights, the Civil Rights Era in America, it was Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Count Basie put the key in the door. They set it up that he could succeed.

Kelly 30:01

And yet, as we get into the later civil rights movement, there are people who are complaining that these three are not doing enough, that they are, you know, especially Louis Armstrong gets accused a lot of Uncle Tomming. Could you talk a little bit about that? And I imagine it was very hurtful to these musicians who were trying to change America, who were trying to find a way to also make a living and help their bandmates make a living, to be accused of not doing enough.

Larry Tye 30:33

So I'd love to talk about that, and exactly the way that you set up the question. I'd love to do it through the eyes, and through the understanding that we have today of Louis Armstrong. When I grew up, and watched him on television and watched his mugging and watched his handkerchief waving, all the things, it was easy to not take him as seriously as an artist, as I should have known that I should have been doing. And when we go back and look at the record, we see a number of things. One, we see that he understood perfectly, that it was not a contradiction, to be an artist and an entertainer. Nobody who knows anything about jazz and my experts on this, to start with were two guys named Wynton Marsalis and Jon Batiste, two of the preeminent jazzmen of today, nobody would begin to say that they weren't building standing on the shoulders of people who came before. And if you were a trumpet player, you were standing on Louis Armstrong's shoulders. If you were a lover of jazz being taken to new levels, any jazz artist understands Armstrong's contributions. He felt like his public art of of understand it better understood it better than whether it was Black public or white public, that he was as serious as a musician could get. But he did what I think was an extraordinary thing back in the early days of the civil rights movement in Little Rock, Arkansas. It was one of the most violent confrontations in that era in the 1950s of the civil rights movement. It was when an order had been given by judges to desegregate the public high school in Little Rock, and Black children were subjected to unconscionable heckling, and made to feel as unwelcome as they in fact, were at that previously all white high school. And President Eisenhower was sort of wavering on what he ought to do. The governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, was doing a George Wallace. People, I think, are probably more familiar with what George Wallace in later years did, saying, "I'm going to stand in the courthouse door and stop these kids from coming in." Louis Armstrong wrote a letter to the president, basically calling him a gutless so and so for not escorting those kids safely into the school from the beginning. In fact, Eisenhower later did send in federal troops, whether he did it because it was Armstrong called him out whether it was just the right thing that he did, and just not as quickly as he should have done it, we'll never know. But Armstrong got more letters to the editor and newspapers across America, attacking him. How could he? He should go back to Africa, he should do all kinds of again, things that in a polite podcast we won't talk about, because he had stood up in a way that most Blacks of the era were rightfully afraid to do. And the way that somebody was appealing to white audiences, genuinely would never have done, Louis Armstrong did it. He did it from the earliest days in New Orleans, and people like me, were just not smart enough to have seen it, and to have looked beyond the mugging he did on stage. He was an entertainer. He was a proud Black man. And he was in my mind as important, a civil rights leader, as Martin Luther King would later recognize.

Kelly 34:17

So one of the things I found most surprising in this story was not just the amount of international travel that all three of them did, but that some of this travel was sponsored by the State Department, that they were really on a mission of international diplomacy. Could you talk a little bit about that, how that came to be, and how that's important to the way that we think about them now?

Larry Tye 34:39

So it was partly a function of Cold War politics in America, that our adversary, nobody had to ask who America's number one enemy is. It was the Soviet Union. And the Soviet Union was accusing America rightfully, of being a racist place. And what better way to show just how embracing their country was of these three Black men, than sending them across the world, where they were drawing audiences in the 10s of 1000s. It was just extraordinary how well received they were everywhere they went, including in the Soviet Union. And what better propaganda tool could America have had than these guys, who I think, hesitated about whether they ought to go out and represent a racist country. And they knew that they were being sent as showpieces, suggesting that racism wasn't what people were reading in, in a Russian newspaper, that in fact, these were people who were toasted in their own country. And they had to bite their tongue repeatedly as they did these trips, but they did them. They were incredibly patriotic and proud Americans. And they decided that all the things that they were doing to promote equal rights back in America wouldn't prevent them from being out there and being ambassadors for a country that had problems but was trying to get better.

Kelly 36:08

You've mentioned a few times their bandmates, and I think it's important to highlight that while these are three extraordinary and talented individuals, they this was all very much a large effort. All of the work that they did, they had bandmates. They had managers, they had people who helped them on the road, they had lawyers. Could you talk a little bit about that, and what you learned when you were interviewing the bandmates about this, this sort of team effort?

Larry Tye 36:36

At times the bandmates were cryptic about, especially Duke Ellington, because Ellington at times, pushed the limits of claiming for himself things that in fact, his bandmates had contributed to, but generally, everybody who worked for these musicians, and that meant people who played in their band, people who traveled with them on the road, said that they were three people who were enablers. They enabled their bandmates to make a living, which was not easy for Black men back then. They enabled them to get publicity. And there was seldom, I would have a hard time thinking of any prominent jazz performer, male or female, Black or white, who didn't spend some time with one of these three, and wasn't better for it and wasn't better known for it, though, just, they were the first ones to say that they were the public face of a bigger world. And that wasn't just the world of Black America, it was the world of their particular bands. And the idea of these guys remaining on top for 50 years was partly because they had people who thought it was so much fun to work with them, that they would put up with terrible conditions of being on the road when questions of were they gonna be lynched. All of these things, when you have Duke, or Louis or the Count, said, "Come with us," they went.

Kelly 38:13

So it's probably worth noting that while they were incredible people, they were not saints. They, you know, each of them had their own their own idiosyncrasies, their own foibles, their own vices. Could you talk a little bit about that just to sort of humanize them and not make them sound like just just jazz gods?

Larry Tye 38:34

Great. So let's just pick one area to look at as a lens into the fact that these three weren't saints. And that is the area of understanding the meaning of a word, faithful. And they were, Louis Armstrong had endless affairs with women, he had four marriages. And even with his last and by far best marriage, he was still unfaithful and his wife knew that he was unfaithful and put up with it because there was enough good in him and, and she felt that he was trying. Count Basie's wife threatened to and at times, did leave him because she knew how unfaithful he was. And Duke Ellington stayed married to the woman who he had stopped living with and had largely stopped communicating with very early on in his marriage, and he stayed married, because it was easier for him to fend off all of his mistresses wanted to marry him by saying, "I'm already married. And you wouldn't want me to sacrifice the money that it would take for me to get a divorce." And it was, on the one hand, endemic on anybody be they a politician, or baseball player or musician who was traveling for 300 days a year. There were temptations out there on the road, temptations to drink, temptations to smoke pot the way Louis Armstrong did just about every day of his adult life. There were temptations, Count Basie, the first time he would get to a new town he'd want to know where the racetrack was, and before he was practicing with his bandmates, he was off to the racetrack. And Duke Ellington, I got on a magnificent tour of Duke Ellington's life, in New York, by his granddaughter, and on our itinerary was the place the places where he performed, the places where he lived, and the places where he stashed his mistresses. And it was just all of these guys were, on the one hand, deeply religious, and on the other hand, violating one or more of the commandments, at most points in their lives.

Kelly 40:51

So there's obviously much more in this book, we're not going to get a chance to talk about. Can you tell people how they can get a copy?

Larry Tye 40:58

So they can go, and this is my bias, to start out with go to their favorite independent bookstore, in their community, wherever they are. And they could go to the website of my publisher, which is Harper Collins. And they can go to the place where most of them are going to end up going anyway, which is Amazon. And it's available everywhere, for pre ordering and ordering and ordering, as Father's Day and other gifts. But I would say who I was writing the book for more than anybody, are of young people of my children's generation who grew up understanding there was something called Jim Crow in America, but would never want to sit down and read a biography of Jim Crow in America. And so what I tried to do is disguise that whole understanding of our Civil Rights and pre Civil Rights Era, disguising it by writing a book about three of the most toe tapping magnificent musicians ever to be born on this planet.

Kelly 42:03

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talk about?

Larry Tye 42:07

Yeah, so I'd love to talk for one minute if we could about why the book is called "The Jazzmen," rather than the jazz players or the jazz women. And that is, for a reason, which I'm sad about, which is that while there were extraordinary vocalists, female vocalists of this era, people like Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday, there were no band leaders who had nearly the expectation of being on Mount Rushmore of jazz, like these three. And so I have a whole chapter on side women because they were incredibly important. But unlike today, women, and especially Black women, had a double stigma, the stigma of being Black, in an era when Blacks couldn't do the things they ought to have been able to do, and the stigma of being a woman in an era when jazz among all the music forms, I think, had a special sexist element to it. And I wish if I were writing about today's era, I would figure out another title and a lot of people, I'm sure we'll be upset with the idea that it is jazzmen. And I think it's important that it be jazzmen, because we have to understand the gender biases, as well as racial ones.

Kelly 43:29

Larry, thank you so much for speaking with me today. I've really enjoyed learning more about these three musicians and found myself going and ordering some jazz music because I was so inspired to to listen to their music.

Larry Tye 43:43

I love that and it's been great to be with the Kelly.

Teddy 44:40

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain, or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Larry Tye

Larry Tye is a New York Times bestselling author whose latest book — a joint biography of Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Count Basie — looks at how these three maestros wrote the soundtrack for the civil rights revolution. It will be released by HarperCollins on May 7. 2024.

Tye’s first book, The Father of Spin, is a biography of public relations pioneer Edward L. Bernays. Home Lands looks at the Jewish renewal underway from Boston to Buenos Aires. Rising from the Rails explores how the black men who worked on George Pullman’s railroad sleeping cars helped kick-start the Civil Rights movement and gave birth to today’s African-American middle class. Shock, a collaboration with Kitty Dukakis, is a journalist’s first-person account of ECT, psychiatry’s most controversial treatment, and a portrait of how that therapy helped one woman overcome debilitating depression. Satchel is the biography of two American icons – Satchel Paige and Jim Crow. Superman tells the nearly-real life story of the most enduring American hero of the last century.

Tye’s most recent books look at how two U.S. senators helped shape their times. Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon explores RFK’s extraordinary transformation from cold warrior to fiery leftist. Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy probes America’s prolonged love affair with bullies.

In addition to his writing, Tye runs the Health Coverage Fellowship, which helps the media do a better job reporting on critical issues like pandemics, mental health, and high-tech medicine. Launched… Read More