Single Irish Women & Domestic Service in late 19th Century New York City

As many as two million Irish people relocated to North America during the Great Hunger in the mid-19th Century. Even after the famine had ended, Irish families continued to send their teenaged and 20-something children to the United States to earn money to mail back to Ireland. In many immigrant groups, it was single men who immigrated to the US in search of work, but single Irish women, especially young women, came to the US in huge numbers. Between 1851 and 1910 the ratio of men to women arriving in New York from Ireland was roughly equal. Irish women often took jobs in domestic service, drawn by the provided housing, food, and clothing, which allowed them to send the bulk of their earnings back home to Ireland.

Joining me to discuss Irish immigrant women in the late 19th Century is Irish poet Vona Groarke, author of Hereafter: The Telling Life of Ellen O'Hara.

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The transitional audio is “My Irish maid,” composed by Max Hoffmann and performed by Billy Murray; Inclusion of the recording in the National Jukebox, courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment.

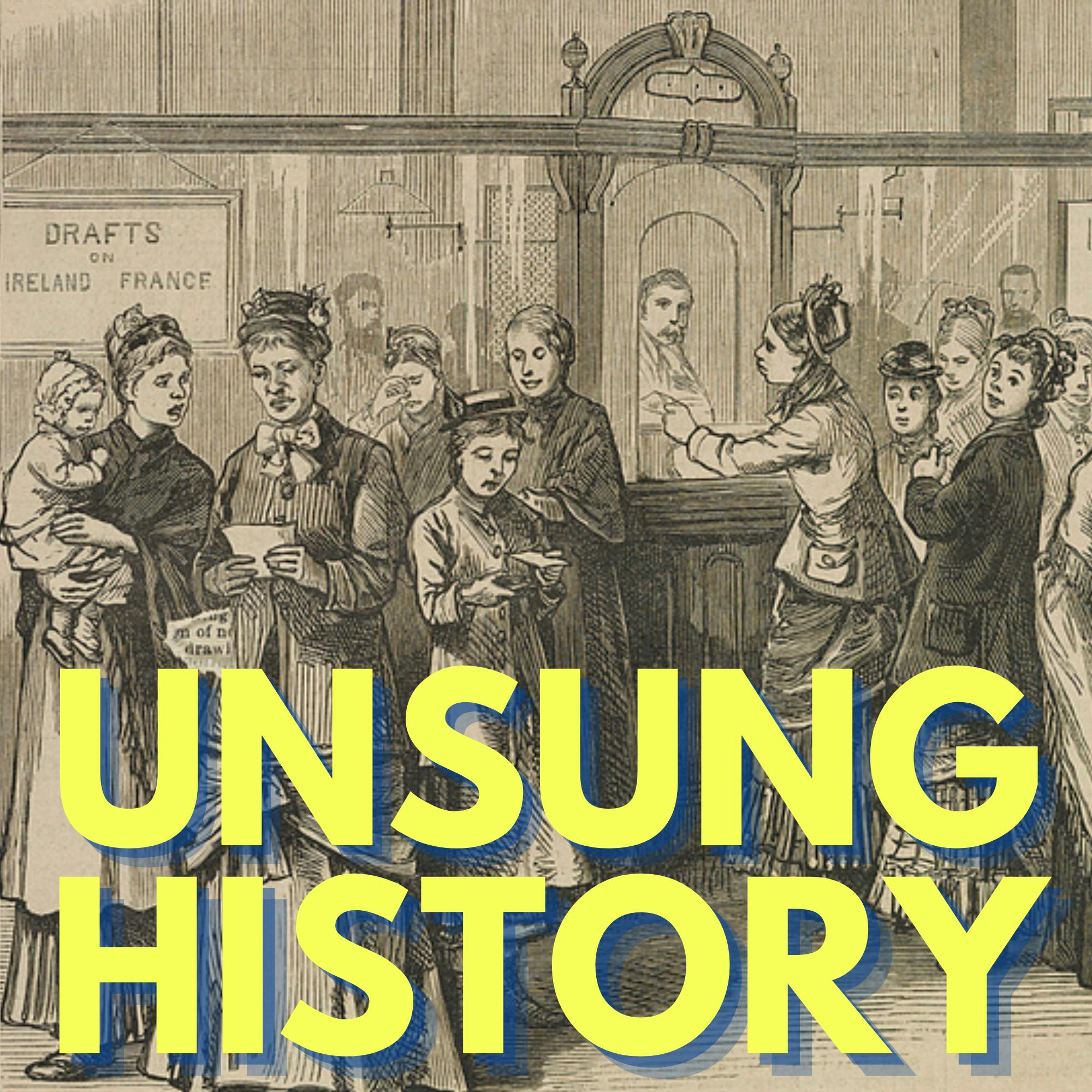

The episode image is: “New York City, Irish depositors of the Emigrant Savings Bank withdrawing money to send to their suffering relatives in the old country,” Illustration in: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, v. 50, no. 1275 (March 13, 1880), p. 29; courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; no known restrictions on publication.

Additional Sources:

- “Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: Irish,” Library of Congress.

- “The Great Hunger: What was the Irish potato famine? How was Queen Victoria involved, how many people died and when did it happen?” by Neal Baker, The Sun, August 25, 2017.

- “The Potato Famine and Irish Immigration to America,” Constitutional Rights Foundation, Winter 2020 (Volume 26, No. 2).

- “Immigrant Irishwomen and maternity services in New York and Boston, 1860–1911,” by Ciara Breathnach, Med Hist. 2022 Jan;66(1):3–23.

- “‘Bridgets’: Irish Domestic Servants in New York,” by Rikki Schlott-Gibeaux, New York Genealogical & Biographical Society, September 25, 2020.

- “The Irish Girl and the American Letter: Irish immigrants in 19th Century America,” by Martin Ford, The Irish Story, November 17, 2018.

- “Who’s Your Granny: The Story of Irish Bridget,” by Lori Lander Murphy, Irish Philadelphia, June 26, 2020.

- “The Irish-American population is seven times larger than Ireland,” by Sarah Kliff, The Washington Post, March 17, 2013.

- “Irish Free State declared,” History.com.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. In today, today's episode, we're discussing Irish immigration to the United States, especially the immigraton of young Irish women to New York City in the late 19th century. In the middle of the 19th century, Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom, relied heavily on the potato as a food source for the tenant farmer population. Many tenant farmers used most of their land, to grow grains to sell to their absentee English landlords and reserved a small portion of the land for potatoes for sustenance. Potatoes could grow in the worst soil, which made them an attractive crop. But this over-reliance on potatoes, and on one particular variety of potato, the Irish Lumper, proved disastrous in 1845, when the Phytophthora infestans infected the potato crop, and ruined up to half of it. By the end of the Great Hunger in 1852, somewhere between one and one and a half million Irish people had died, and one to 2 million had fled the country. Because the Irish blamed the English and the way they ruled Ireland, for much of the misery, many chose to flee to the United States.

Even after the potato blight had ended, many in Ireland were desperately poor. And it wasn't unusual for families to send one or two of their teenaged or early 20s children to the United States to find work, and to then send money back to their families in Ireland.

The Irish immigrants who came to the US often made it no further than the port city where they landed, especially New York and Boston. With few resources, these immigrants immediately started looking for work. In 1860, about a quarter of the population of New York City was foreign born, and nearly half of those were Irish, totaling about half a million Irish immigrants. Many single immigrants from other countries who came to the United States in search of work were men. But immigrants from Ireland were just as likely to be women. Between 1851 and 1910, the ratio of men to women arriving in New York from Ireland was roughly equal. It's estimated that by 1890, the median age of Irish women coming to New York was under 20. Most of these Irish women, untrained for other employment, found jobs in domestic service. In Kingston, New York, north of New York City, a whopping 94.5% of employed Irish women in 1860, worked as domestic servants. As with other immigrant groups, once a pattern of employment was established, it fed upon itself. The Irish American community helped each other find employment via word of mouth, and they connected each other with the jobs that they knew. Although slightly less dangerous than the backbreaking physical labor that employed Irish men, Irish women working in domestic jobs, still faced grueling and physically demanding labor, working six days a week, with only two half days off. They were often the first to rise and the last to bed every day. One of the most difficult aspects of domestic service was the loneliness of the position, especially for those who were the only servant in a household where the family did not treat them as equals. Still, there was a particular advantage to domestic service that made it especially appealing to Irish women who were sending money back home. The wages were low, but domestic servants lived in the household, and they didn't have to use their wages on lodging, food, or even clothing, since they wore uniforms to work. They could send nearly all of their earnings back to their families who desperately needed the money. In 1861, women were sending an estimated 80% of the money that was flowing from the United States to Ireland. In Ireland, this needed money went to rent, food, education, many other things. It was also used for passage for siblings to travel to the United States in a form of chain migration. Irish immigrant women may have been hired into service in large numbers, but that didn't stop native born Americans from disparaging them. It wasn't unusual for help wanted ads to state preferences for American girls, although those same American girls did not want the job, preferring to work as shop girls, or in other less stigmatized jobs. Newspaper cartoons made fun of "Bridget," a negative caricature of the Irish maid so prevalent that some women named Bridget would change their names upon arriving in the United States. These immigrant women worked hard, both to send money back to Ireland and to save for their own eventual families. They helped their daughters pursue a great diversity of jobs. And as a result, only about 19% of their daughters worked in domestic service. In the late 19th century, the Irish Home Rule Movement began, agitating for self government for Ireland within the United Kingdom. In April, 1916, Irish Republicans fought the British in Dublin in the Easter Rising. Although the rebellion was put down, the calls for independence continued. In 1919, the Irish Republican Army or IRA launched the guerrilla Irish War of Independence, which resulted in the 1921 Anglo Irish Treaty, establishing the Irish Free State, a dominion of the British Empire. The parliaments of Northern Ireland opted out of the Free State, and remained part of the United Kingdom. In 1948, Ireland's Parliament passed the Republic of Ireland Act, which went into effect in April, 1949, and which cut all ties between Ireland and the British Commonwealth. Ireland became a member of the United Nations in December, 1955. As of 2013, there were seven times as many Americans of Irish descent, as there were people living in Ireland itself. I'm joined now by Irish poet, Vona Groarke, who has written a book about her search for information about her great grandmother, Ellen O'Hara, who was an Irish immigrant to New York City in 1882. That recently published book is called, "Hereafter: the Telling Life of Ellen O'Hara."

Hi Vona. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Vona Groarke 9:44

My pleasure.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:45

I was just thrilled to read your book. It is beautiful and it was just a really wonderful read. I wanted to start by asking you about this family connection. You're writing about I believe your great grandmother. And so so talk to me, you didn't intend to write this book initially. What, how did you get into this this story?

Vona Groarke 10:06

Well, it kind of happened by accident, Kelly. So I had a fellowship in the Cullman Center in the New York Public Library. And one lunchtime I found I was working on a different project altogether. On one lunchtime, I found myself just kind of remembering the fact that I have this family connection with New York. My mother was born in New York and lived here until she was, and lived there until she was 12 years of age. And she had lived with her grandmother. And I thought, "Oh, well, I wonder, could I find out anything about that grandmother," because I didn't really know very much. So being an NYPL, I had a lot of different archives at my disposal. So I started just having a look through various search engines and just seeing if she showed up on passenger lists, if she showed up on census records, if she showed up in Polk Directory. And I realized that there was very little about this woman, in fact, and that kind of intrigued me, because I thought, how can it be that some lives are recorded in minute and scrupulous detail, and some lives seem to have no light thrown upon them at all. And as a poet, of course, I'm more interested in the latter category. So I began to think, "Right, how would you tell a story that has very little evidence, that has some anecdotal evidence," because my mother told me some stories about her grandmother that has some archival presence, very little, but some. And then where would I go to find out the rest of the story? And I thought, "Okay, the obvious thing to do is to start looking at historical research that has been done into the period while Ellen was in New York. And what do I know about her? I know, when she was born, because I have a baptism record for that in Ireland. And I know when she died, so how can I fill in little bits in between? And where do I go?" And I started thinking, "Well, what did women do when they arrived in New York, mostly from Ireland, with the education they had, with the very limited resources that they had? Really what they had, was an interest in working hard, an ability to work hard. And, and they had other people who were already there. So they had contacts and that's kind of all, they had, like many immigrants, I suppose. They had an appetite for self improvement, and they had some contacts. So a lot of them went into domestic service. A lot of the women either went into domestic service in the cities, or they worked in mills. But if you worked in a mill, you had to get yourself to the mill, you had to feed yourself, you had to get yourself home, you had to clothe yourself, and you had to pay rent, to live someplace. If you were a domestic servant, you were you were paid less, considerably less, but you didn't have any of these expenses. You were fed, you were clothed, and you were given someplace to sleep. So you didn't have overhead. So in fact, it worked out quite a bit better. And it meant that anything they earned was, was theirs to spend, or as most of them did to save, and then send sent home to Ireland. So it was an attractive place, it was also a safe place for them to be because as long as the the house they were in was a congenial one, you know, they were they were in a safe kind of a capsule. So I found that that was a very popular choice. So I thought, well, that's probably what Ellen did. And then I know from my mother, that she had run a little boarding house for young Irishmen herself. So I thought, "Okay, how did she get from being a domestic servant, which is kind of the lowest of the low in terms of of New York work to owning a little boarding house herself?" And how I found the answer to that question, and to all the other questions I had, was by reading the historical research that other people had done, about domestic service, about the lives of women, about the lives of immigrants, about the social network of immigrants, about the kind of clothes that they wore, the kind of food that they ate, and so on and so forth. And little by little, I began to build up a picture of what it was, like, most likely for Ellen. Do I know that it was exactly like this for Ellen? I don't, but I'm using Ellen as a kind of example of the sorts of lives that women like her had. So I came at it that way, and, and then I found a piece of information that was particular to her, and which was a kind of a tragic piece of information, which was I found her marriage certificate. So I know who she married. She got married in in 1897. And in the 1900 census, she shows up with her husband and two children. And so I know that she had two children, right. And then the next piece of actual evidence I find is on a passenger list for a ship that's going back to Ireland. And she's on there with her two children and no husband. And then I find three weeks later that she comes back on her own. So I know that she left her children at home, in Ireland with her parents. So this was the first time that I had something that was really the start of the real story, her story, that wasn't anybody else's story, it was just her story. I don't think that was a common occurrence. But it was her life experience. And so really, the book got written out of the research about the common experience, and then what I could find about what was particular to her. And so that's how I kind of put it together.

Kelly Therese Pollock 15:38

Yeah, can you talk a little bit about genealogical research? So I've dabbled a little bit in it. And, you know, I, there were some familiar moments to me. It's like finding like, "Oh, that name matches? Is that it? You know, is that so?" So, can you talk about that, and sort of, especially these are common names, right? Ellen O'Hara is not a super unique name. And what that means as you're sort of looking through and trying to piece together, "Is this the person I'm looking for or not?"

Vona Groarke 16:03

Yeah, I sometimes think that if anybody comes looking for me, in a couple of 100 years time, they'll have an easier job, because I have I don't think anybody else in the world has my name, I'm Vona Groarke, and both, those are both unusual names. Ellen was Ellen O'Hara, which you're quite right. It's not. It's not it's not a really unusual name. But one of the delightful surprises, because I did have surprises where I just thought, "Oh, I cannot find what I'm looking for. It's so frustrating." But one of the delightful surprises was that if you have a name and a date of birth, you are well on your way to getting almost everything that is available about somebody. So there weren't any other Ellen O'Haras that I could find in the records, who had her date of birth. And of course, I had that from from the records in Ireland. So I had the two key pieces of information. And that meant that I could find her in census records. It should be very easy. My my, my difficulty that I encountered was that she lied about her age. And she was a not a few years older. And in talking to other women, you know, when I was researching and writing the book in America, they said, "Oh, my grandmother used to do that too, all the time. And if we ever had to bring her to the doctor, there was always a big kerfuffle, where she would send us out of the room while she gave her actual date of birth." But I kind of grew wise to Ellen's Ellen's little fibs about her age, and I was able to able to still locate her that way. And also because I knew the names of her children, then in the census records, there actually wasn't anybody else who had her name and her two children. She did I should say that she did get them back to America, in in much later. They were in Ireland for 12 years. And then she got she brought them back to America. So after that, I can find her in the records because she's the only one who was Ellen O'Hara, but she changed her name to O'Grady because that was her husband's name, who has a James and an Anna. And that was her son and her daughter. So actually, it's amazing with genealogical research how far you can actually go with just very few, but very specific pieces of information.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:20

Yeah, did you ever, as you were sort of putting this idea together, start to think there's just not enough here, I just can't do this, because that's how I, I've thought about writing about my grandmother. And it's a similar sort of thing that like, I can find passenger record on a ship, I can find, you know, maybe birth certificate, but there's just not that much there. And it always sort of stops me and goes back to, "Can I do this?" So how did you sort of navigate that?

Vona Groarke 18:45

I couldn't have written a straightforward historical account of her life that that claimed to be true and accurate. I couldn't, there was not enough information to do that. But I'm a poet. And so I thought, "Okay, I've got some very few, but still useful pointers as to what her life would have been like and to what her life actually was." And I thought, "Right, how can I use them to tell a story and I thought, well, I could use my imagination." Novelists do that all the time. And they make up a story and they fill in bits and pieces of historical accuracy. But the rest is drawn from conjecture, perhaps, informed conjecture, perhaps really not informed. But I thought, "Okay, I could do that. But I don't want to write a novel. Because there are a lot of novels about the Irish immigrant experience in in New York and the other cities on the coast." I thought, "I don't want to do that." And also because I'm not a novelist, I thought there's a good chance that I won't really do that well. So I thought, "Okay, what what, what could I do?" I thought, "Okay, I could probably write a sequence of poems about her and I know how to do that because I've already written 12 other books of poems," but I thought, "Well, no one will ever read that." And I thought if I'm going to rummage around into this woman's life who had a hard life, she was hard done by in many ways, then I want I want to write a book that is fair to her, and that isn't all about me and what I know how to do in terms of poems, but I want to write a book in which I can somehow I conjure her voice and, and make it seem credibly, that she's involved to some extent, right. So if I was writing a novel, I could make it seem like she was completely 100% involved, because I could make her a character. So I'm not doing that. I'm not having her be naught percent, because that seems like that would be to dishonor her. So I'm having her somewhere in the middle. And I thought, "Okay, I think what I really want to do is to write an account that acknowledges as it goes along, that it's watching itself, that it's checking itself, that it's noticing where it makes assumptions that might be wrong, that might be entirely incoherent, or baseless. And when it does that, I want to have some mechanism whereby the book can say, "Look, you've just, you've just said something that might not be true." And I thought, "Okay, how do I do that?" And I thought, "I know, I'll create a character who was watching me write her story. And every time I get something wrong, she will laugh at me, or she will say to you, 'Oh, you think you know it all, but you don't.'" And I tried it out. And I kind of, I felt like I had created a character who lived with me then for a couple of years while I was writing and editing the book. And honestly, it really did seem to me like she was there as a kind of a judging voice on the book that I was writing. And that was very useful to me, because it became a kind of a dialogue between me writing the book and between her who owned the life. And, and, of course, everything that I had her say, was drawn from the historical research that I had done. So I didn't have her say, you know, "We worked seven hour days" when I knew from research that she worked a 15 hour day. So I had her account for her life in a way that was drawn from the historical sources. But I also had her with a personality that was skeptical, and that was a bit abrasive, and that was a bit resistant to my attempts to write the book, because that gave it a dramatic tension. And for me, that was more interesting to write than somebody who was saying, "Oh, aren't you great now to be writing my story. "It was much more interesting to have somebody say, "Oh, you think you know it all, but you don't. You got that wrong, and you got this wrong." So you know, I think any, any writer wants to write a book that's interesting to them in the writing. And this one certainly was really interesting to me to write, because it was a new kind of form for me. But I have discovered that it's much easier to conjure a ghost than it is to get rid of a ghost.

Kelly Therese Pollock 23:04

I love that. And so it almost in a way gave you this, this relationship with at least a version of who your great grandmother might have been in a way that you didn't get to know her in real life.

Vona Groarke 23:17

Yes, exactly. I didn't. I know that my mother was very fond of her. But my mother has been dead a long time. So I can't go back to her and say, "Is this right? Is that right?" There's nobody alive, who knew her, absolutely nobody, and I don't have anything that I know belongs to her. I am I have, I have ideas about a couple of the things that I decide belong to her. And I have some sort of, you know, not entirely logical reasons for making that decision. But there's nothing that I can say this was in her hand at one time. I have no letter I have no photograph. I have no teacup. I have nothing of the kind. So you know, she's she's not known to me in that sense. But I feel it's the strangest thing, because obviously, she came from my imagination, but I almost feel like, like, that's not entirely the case. And that I have learned something about somebody who's not entirely from my imagination. So I you know, it's a it's a delicate kind of balance between sounding like you're, you know, like, like, you're sitting around a Ouija board and believing in visions, or are actually just thinking, you know, there are there are points where, I think have succeeded in this because it doesn't sound like me. And I guess that's that's part of the craft of writing as well. You don't always want us to sound like yourself. You need at times to throw your voice into another character. And, and that's what I think happened here. I learned how to throw my voice into a voice that just had a I suppose a kind of authenticity that talked a little bit like I think a woman of the time who came from Ireland who would have had Irish usage in her English, but who would have also had some Irish language in her English usage, but who lived in America for, for all of her adult life past the age of 20. So she would have had American usage as well. So, you know, the to get her voice right, to get the way that she used language some way right, to get all of that was, was a matter of chance but I think, I think it's okay, I think it's okay. Yeah.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:32

So you mentioned, of course, that you're a poet, and you have a note at the beginning about the the form of poem that you decided to use? Can you talk a little bit about that? Just for maybe listeners who don't know a lot about poetry, you know, how, what the different forms do, you know how that sort of changes the way you might imagine a poem, you might, you know, experience a poem?

Vona Groarke 25:54

Well, I suppose the first thing to say is that the the poems that are in this book are not, they're not poems in the sense of like, usually, when I, when I, when I write poems, they're quite kno lyrics. And sometimes they're kind of complicated, and they're very interested in the surface of language and, and, you know, metaphor and sound and rhythm and all those things that poems tend to be interested in. And these poems are not like that. So essentially what they are, is, is just a way of drawing on a kind of folk tradition. So I have this character, and I imagined her sitting in the corner of my office in the New York Public Library, watching me, listening to me, judging me, sometimes complaining to me about what I'm doing and so on. And I think, "Okay, so how do I put some kind of a shape on, on what on what her voice is, so that it doesn't sound like mine?" Because my voice is present in the book as the researcher, and it's a version of myself, it's not exactly me, but it's a version of myself. But it sounds more like me than it doesn't sound like me. So I don't want her to sound like me as well, because then you've got a book that is kind of monotonal or monotonous. So I thought, "Okay, well, maybe there's a way to do this by drawing on the kind of folk tradition and poetry." Really, what I want to do is to have a kind of a shape on what she says, to make it look different on the page to what the bits that I'm writing, you know, directly look like. And, you know, the idea of having a little bit of rhyme every now and then or a little bit of half rhyme, just to have a kind of musical quality to the voice, that could be useful. So I started thinking in terms of sonnets. So really, they're just 14 line poems, where where the 14 line pieces of language where she talks, they don't do traditionally what sonnets do, but they're just a way of putting shape on what it is that she says, so that it sounds a little bit different to what I say. And so that looks different on the page. And so that it allows her to kind of just sound so all the sonnets, I think sound a little like each other. And then all the prose pieces that are in my voice sound like each other. But prose pieces do not sound like her sonnet pieces. So there's a bit of tension between them, which I think is useful in terms of reading the book. But they're not, they're not hard. They're conversational. They're just somebody telling a story that happens to be in 14 line blocks.

Kelly Therese Pollock 28:23

Yeah. So in this research, you also found a bunch of other Ellen O'Haras. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that and sort of your choice to include their stories, a little bit of their stories in the book as well.

Vona Groarke 28:37

Yeah, so I've said already that, once you have a name, and a date of birth, you can go a long way towards tracking somebody down. But if you don't have the date of birth, and if you just put in the name, then you yield loads, and loads and loads of people, unless you're called Vona Groarke, likely yield loads of people who have that name. And I started doing that just to see well, it was kind of a game really, it was kind of a game to see who else was called Ellen O'Hara, and what kind of lives do they have? And were they in any way like ours, or what I know of her or what I'm giving her in terms of her life? And I found that some stories of women who had her name, or were stories that were based on advantage, and having a little bit of money and having a little bit of prestige, and a social circle and a place in society, I suppose is a better way to put it. And some women of the same name as her had much worse lives than her. I mean, hers was was hard enough and plenty tragic in its way. It's not a good thing to lose your your tiny children, and have to give them up for 12 years. But other women of the same name had even even worse experiences than her. And I thought it's interesting to me that the same name can yield so many different kinds of stories. And I because the book is really about how you tell a story, as much as it is about the story, I thought, well, you know what I've kind of found this other story, which has to do with just the name. And some of the stories, I found in newspapers. And some of them were kind of funny. And then I found this extraordinary character, which right at the start, and I thought was my Ellen. And she was Deputy Police Commissioner in the New York Police Force, the first woman to ever hold the position. And for about a minute and a half, I thought it was my Ellen, and then I realized it's definitely not my Ellen. But her story was kind of extraordinary, because she was a sort of Puritan person who, who believed that the fashions on display in department stores shouldn't be showing any cleavage or even any arms that the French fashions were, ought to be, you know, protected against, as the New York women should be protected from these insidious French designs. So there was a kind of a comic element to the stories of her time in the police force. So I thought, Well, look, there's not there's not a whole lot of comedy in the book. So I think this is an opportunity to include some different stories on some different notes. And I was very glad of them, you know. And, of course, at a certain points, I thought, "Well, these, these are kind of at a tangent to the real story, I'm telling. I wonder, should I leave them out?" And I tried it without them. And I thought, you know, what, there's something missing, there is actually something missing that just this idea of, of these other women and the lives that they weren't able to make of the same name that they had, and just different circumstances, I think that tells a story that's not unrelated to the story of Ellen.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:38

Yeah, yeah. And one thing about that Ellen O"Hara, of course, is that we have actual pictures of her. I love that you have graphics throughout this book, even though of course, as you mentioned, you don't have a photograph of your own great grandmother, but you're able to find other graphics to sort of complement the story. Can you talk a little bit about that? Because I think it really does add to it.

Vona Groarke 32:01

I think so too. You know, all the time, when I was writing this book, I was feeling my way by imagining what what the world was like that Ellen lived in. So I had certain things that were still there to me. So some of the houses that I knew she lived in, one of the apartments and houses that I knew she lived in from census records, some of them still exist. So I was able to go and stand outside them and have a look at them. And a couple of them were were were gone. A couple of them were around where Fordham University is now, but they're not, they're not there anymore. But just being able to see some physical connection to her life was useful to me. And then I began to wonder, "Well, what clothes would she have worn?" And then if you're a servant, for six and a half days a week, and you're trying to mind your money all the time, because it's needed at home, then what could you do with the few little bits of money that you might allow yourself? What could you do with that in terms of your clothes, because she's a young woman, and she, she's gonna want to dress up, and she's gonna want to, to meet other women and to meet men and all of that. So how can she? What could she do with very little money? So that was kind of interesting research for me to see what what were the kind of day dresses on the house that you could make very little money. So all the time I was thinking of the stuff of a life, like, what would she touch? What would she have worn? What would she have eaten? "There was a lot of research into what the right kind of food for her time was what the servants would have been given to eat, what they would have been cooking for, for, you know, the employers. And I found the Merchant, the Merchant's House Museum, really, really helpful to me in New York, in that respect, because they they have the downstairs house as it was when the Merchants lived there. And then they have some maids' rooms upstairs, that they have still got the furniture from, from the time that the maids were there, and they have their own census records. And the census records show that they were Irish maids, who lived up there at the top of the house, on East Third Street in New York. And so those kinds of little things were ways into the character. You know, you start with an abstract idea, I'm going to build a character, but the way you get to build the character is really through through material objects you imagined. What kind of shoes that you wear? Was she thin? Was she not thin? And what kind of hair did she have? What would her accent have sounded like and so on and so forth. Like what objects would she have had would she have owned very little, probably a set of rosary beads and you know, a pen and things like that for letters home but very little in the way of concrete objects. So, but the minute you start thinking in terms of, of those objects that allow you in on the character, then you can start building all the bits that are a bit more abstract that are a bit more esoteric: her outlook, her her values, her affections, her hopes. But you start to think with with the material objects, and you use them as a kind of a way of, of getting from the practical to the more abstract.

Kelly Therese Pollock 35:09

Yeah. So I want to ask about this story that I really want to be true about how your grandfather ended up back in Ireland.

Vona Groarke 35:20

Yeah, I want it to be true as well. But because of the nature of the story, I'm not sure that I will ever be able to prove it. But it certainly it's, it's the story that exists in the family. And I'm not the I'm not the only one who has heard this story. So I didn't I know I didn't make it up. And the story is that he won. So he was he was married to my grandmother, and they had four children in New York at that stage. My mother was the eldest, she was born in 1924. And he the story is that in 1936, he won a pub in County Mayo in the west of Ireland, won that pub in a poker game. And then they decided to move back to Ireland to take possession of the pub. So I would really like that story to be true. And I'm not entirely sure because as I as I write in the book, my limited understanding of poker leads me to believe that in order to win a poker game, to win a pub in a poker game, you have to have something of roughly equal value to bet. And I don't think he did. So maybe somebody who's an expert poker poker player would say, "Now you've got it all wrong, you can start with, you know, $100. And you can end up with a pub in County Mayo, or you can start with $5, and end up with a pub in County Mayo." And maybe that's the case. But it's a good story. And I love that idea of chance. And, you know, in Ellen's life, she had some bad luck in terms of the man she married, I think that was the was bad luck. She had some good luck as well. But she had some bad luck. And I just love that there are these kinds of random extraordinary things that can happen in a life and change everything.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:09

Yeah, well, it's a beautiful book. So it tell people how they can get a copy.

Vona Groarke 37:15

Well, it's it was published on November the 15th, by New York University Press, and it's available in bookstores. It's also available online through New York University Press. And I think it's very reasonably priced. I think it's $22. And I'm told that it's the kind of book so I don't mean to sound too, too self important. But other people have said to me, after they read it, people have said to me, "I want to buy copies for other people, for my sister, for my aunt, for my grandmother, for whoever," because it kind of tells the story that they would have certain memories of hearing little bits and pieces of it, but it kind of pulls maybe all those different bits and pieces together. So I'm really hoping that it's it's read and enjoyed by people. I mean, it's very, very important to me that I wrote that I have an enjoyable book here. Because it's not like the books of poems where there's something else at work rather than just pure pleasure. But I wanted to write an enjoyable book, because I felt like that was the best way to honor Ellen, whose story it was, not not to write a boring book. So I think I think that was very important to me. I hope that I have achieved that.

Kelly Therese Pollock 38:34

Yeah. Is there anything else that you wanted to make sure we talk about?

Vona Groarke 38:39

Well, I suppose one of the the aspects of the book is that I go thinking about money in the book. And I think about Ellen working, you know, 15 hour days, six and a half days a week as a domestic servant, and I thought, "I wonder how much she earned? And what would she what would that money have meant at the time?" So I do a lot of research about that. And I find out how much she would have earned. And I start thinking about all these women and what they're earning. And I start thinking of all the money that was sent back by them to their families in Ireland, and I'm thinking, "What kind of change would that money have made?" And so I go, I do I do, the thing that we're always told to do is just follow the money. And so I started looking into how much money was was sent back to Ireland by way of remittances, and what percentage of that might have been sent back by women as opposed to men and I find that because of the reasons we talked about at the start, which is that women were able to save money, where their male counterparts, maybe had to had to pay for things that were included in their lives, that they were able to send back more and I have quite a few contemporary accounts that support this idea that women domestic servants sent back more money than any other kind of, of Irish immigrant in the United States. And I also found that the amount they sent back was staggering. It was an absolutely enormous sum of money that they sent back. Now, of course, it got dissipated back to their families. But it was used to pay rent, it was used to bring other younger siblings out to America, it was used for doweries for younger sisters, it was used to improve the livestock on the farms at home, it was used to add on rooms to and to generally improve the quality of of living, for their families back home. And it was used to drain land. And generally speaking, one of the things that I wanted to do in the book is to say, "This is not just an interesting story. But here's a story about the economic contribution of women to Ireland in the early decades of the last century, that really has never been told before, because people think of it as a kind of a sentiment or a tragic story. But look, what a difference the money they earned and sent back made to Ireland." And I have this idea in my head, which is very hard to prove. So I put it forward as a suggestion rather than as a definite argument that the money that they sent back, the improvements that were permissible in Ireland on foot of that money, had to contribute to the confidence of Ireland, when it came to setting up its own state, to the independence movement. And it meant that they were coming from a much stronger position than they had been, you know, 20 or 30 years previously, when just making the quarterly rent was a hard job and just feeding the family was a hard job. And so, you know, I'm putting forward that idea that they were hugely significant in terms of the actual history of the Irish state and their contribution, their economic contribution to that. And I think that's something that might be new to some people it might be something that hasn't really been in the heart of it but much before and I think it's very important to remember that their work made a difference here in Ireland.

Kelly Therese Pollock 42:11

Yeah, that was a really compelling piece. Well, Vona, thank you so much for speaking with me. I really loved this book. And it has me really thinking about how I could tell my grandmother's story, you know, if there are ways that I can I can put that together. So I really appreciate the the inspiration as well.

Vona Groarke 42:30

Thank you very much, Kelly, it's been a pleasure talking to you.

Teddy 42:35

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Vona Groarke

Vona Groarke has published eleven books with The Gallery Press, including eight original poetry collections. A Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library 2018-19; former editor of Poetry Ireland Review and selector for the Poetry Book Society, she teaches part-time at the University of Manchester and otherwise lives in south Co. Sligo, in the West of Ireland.