Harold Washington

In 1983, Harold Washington took on the Chicago machine and won, with the help of a multiracial coalition, becoming the first Black mayor of Chicago. Winning the mayoral election was only the first fight, and 29 of the 50 alderpersons on City Council, led by the “the Eddies,” Aldermen Ed Vrdolyak and Edward M. Burke, opposed Washington’s every move. This week we look at Washington’s rise to the 5th floor of City Hall, who helped him get there, and the struggles he faced once elected.

Joining me to help us learn more about Harold Washington is Dr. Gordon K. Mantler, Executive Director of the University Writing Program and Associate Professor of Writing and of History at the George Washington University and author of The Multiracial Promise: Harold Washington's Chicago and the Democratic Struggle in Reagan's America.

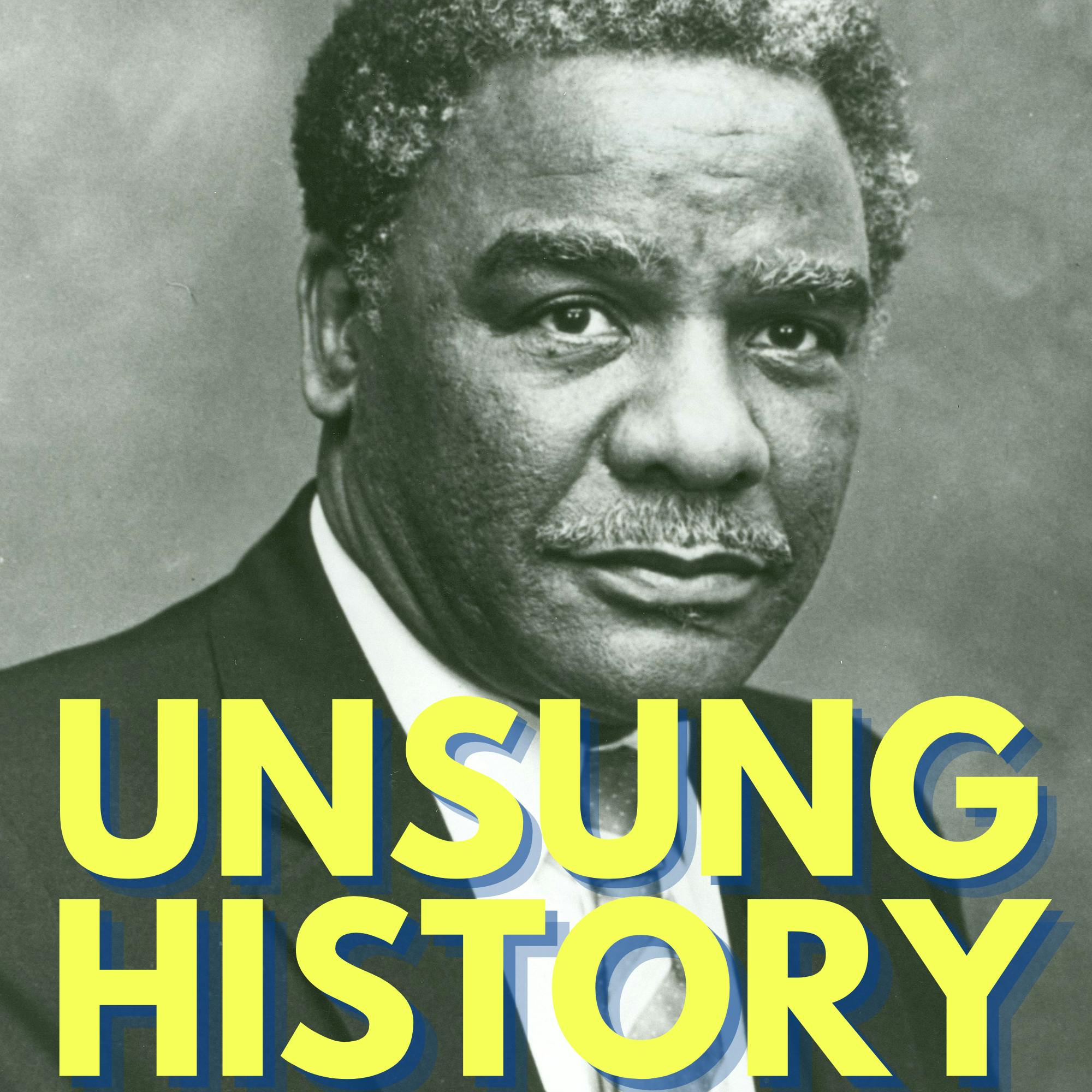

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image is a photo of Harold Washington, US Federal Government, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Additional Sources:

- “WASHINGTON, Harold,” HIstory, Art, and Archives, United States House of Representatives.

- “Mayor Harold Washington Biography,” Chicago Public Library.

- “Achieving the Dream: Harold Washington,” WTTW Chicago.

- “Who Was Harold Washington? A Look Back at the Legacy of Chicago's First Black Mayor,” NBC5 Chicago, April 15, 2022.

- “How Mayor Harold Washington Shaped the City of Chicago,” by Adam Doster, Chicago Magazine, April 29, 2013.

- “Punch 9 for Harold Washington [video],” directed by Joe Winston, 2021.

- “The Legacy of Chicago Mayor Harold Washington [video],” UChicago Institute of Politics, Streamed live on Apr 27, 2022.

- “ILLINOIS SETS UP AT LARGE VOTING; Governor Signs Emergency Bill for House Election,” The New York Times, January 30, 1964, Page 14.

- “Hyde Park Stories: Harold Washington Park,” by Patricia L. Morse, Hyde Park Historical Society, February 22, 2023.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

This week, we're discussing the first Black mayor of Chicago, Harold Washington. Harold Lee Washington was born on April 15, 1922, in Chicago. Washington's dad was a lawyer and Methodist minister, who became one of the first Black precinct captains in Chicago. Washington attended DuSable High School in the South Side Bronzeville neighborhood. Other notable alumni of DuSable include basketball players Maurice Cheeks, and Kevin Porter, singer Dinah Washington, and publisher John H. Johnson. In 1942, Washington was drafted into the military, and he spent World War II serving in the Pacific with the 1887 Engineer Aviation Battalion, where he rose to the rank of first sergeant. He was honorably discharged in 1946. Upon returning to Chicago, Washington studied political science at Roosevelt University in Chicago, serving as class president during his senior year. After earning a JD at Northwestern University School of Law in 1952, and passing the bar in 1953, Washington joined his father's private law practice. Washington's first foray into politics was as precinct captain in the Third Ward Democratic organization, succeeding his father after his death. In 1965, Illinois had yet to redistrict the state following the most recent census, when the governor vetoed a proposed bill, and then a 10 person committee failed to agree on a map. The Illinois State Supreme Court ruled that all candidates for the Illinois House of Representatives needed to run in an at large election across the state. Mayor Richard J. Daley ran a slate of candidates that included Washington, and Washington won a seat in the house. He would serve in the State House of Representatives until 1976. He was aligned with the Democratic machine, but he didn't always follow their instructions. And in 1967, the independent voters of Illinois ranked Washington, the fourth most independent legislator in the Illinois House and best legislator of the year. In 1971, Washington spent a month in Cook County Jail for failure to file income tax returns, a violation that usually resulted in only a fine. Despite his stint in jail, his constituents continued to support him, and in 1976, he ran for and won a seat in the Illinois Senate.

When Mayor Daley died in late 1976, after 21 years as mayor, Washington ran in the special election, against machine candidate, Michael Bilandic. Although he won only 11% of the vote in the Democratic primary, he promised voters he was permanently splitting with the machine saying, " I'm going to do that which maybe I should have done 10 or 12 years ago. I'm going to stay outside that damned Democratic Party and give it hell." In 1980, Washington ran for Congress in the Illinois First District, a majority Black district on Chicago's South Side, winning in a crowded primary against the machine backed incumbent, and then trouncing his Republican opponent with 95 percent of the vote. With Ronald Reagan in the White House, one of Washington's main roles in Congress was as a critic of the Reagan administration's cuts to spending on federal aid programs, which he argued unfairly targeted districts like the Illinois first, and the President's foreign policy, including military intervention in Central America. In Congress, Washington fought for extensions to the Voting Rights Act, and endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment, saying, "To me, the ERA is a non-debatable issue. Black people have suffered from discrimination, degradation and inequality in all areas of life. So on the issue of people's rights, it's easy to identify with the inequities women are facing." Washington won an easy re-election to Congress in 1982, this time, with 97% of the vote in the general election.

Many African Americans in Chicago were looking for a Black candidate to run against incumbent Mayor Jane Byrne. Washington agreed to run, but only if they could register over 100,000 African American voters in Chicago, which they did. Washington was out-spent in the Democratic primary, but he built a multiracial coalition that turned out voters, including those newly registered African American voters, in the largest primary turnout in the city in 25 years. In the February, 1983 primary, Washington won 37% of the vote, with massive support from the south and west sides of the city, winning over Burns 33% and 30% for Richard M. Daley, son of longtime Mayor Richard J. Daley. The general election was surprisingly close, with some high ranking Democrats supporting his opponent. But Washington defeated former state legislator Republican Bernard Epton 52% to 48%. The majority of the city council was opposed to Washington, led by Alderman Ed Vrdolyak, who was also the chair of the Cook County Democratic Party, and Alderman Ed Burke. It wasn't until a court ordered redistricting and special elections in 1986, that Washington finally had the support of a bare minimum 25 of 50 aldermen. In 1987, Washington ran for reelection, again defeating Jane Byrne in the Democratic primary 54% to 46%. Ed Vrdolyak ran against Washington in the general, representing the Illinois Solidarity Party. Washington beat Vrdolyak 54% to 43%, with the Republican candidate coming in a very distant third. Just months into his second term, on November 25, 1987, at 11am, Washington collapsed at his desk in City Hall. Paramedics rushed him to Northwestern Memorial Hospital, but the attempts to revive him failed, and he was pronounced dead at 1:36pm. He was buried in Oak Woods Cemetery on the South Side of Chicago. Joining me now to help us learn more about Harold Washington is Dr. Gordon K. Mantler, Executive Director of the University Writing Program, and Associate Professor of Writing and of History at the George Washington University, and author of, "The Multiracial Promise: Harold Washington's Chicago and the Democratic Struggle in Reagan's America." Hi, Gordon, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 9:38

Thank you. It's great to be here.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:39

Yeah. So I want to hear a little bit about what inspired you to write this book. It's not a biography of Harold Washington, but the story of the Harold Washington Coalition and the movement and the election. So talk to me about how you got started on that.

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 9:54

Yes, absolutely. And you're right. It's definitely not a biography. I think some people have described it as such when I first talked about the project, and I said, "No, no, no, this is about the movement that made this possible." And the moment but also, I think so often Harold's triumph in 1983 has been discussed by itself and not really as much in as part of the larger governing process, right. So it's one thing to win a campaign. It's another thing very much so to govern. And while maybe older Chicagoans and older politicos alike know about the council wars and know about the debates over governing in Chicago in '83, '84, and '85, it usually gets overshadowed by just the election itself. To answer your question more directly, there's, there's a few reasons why I started working on this project. One, I'm not I'm not from Chicago, I should be, I should be very transparent about that. And so so if you're an outsider, I'm very much an outsider. And I know that and I, you know, I, I completely embrace that identity. I totally understand that folks are like, "I get to dismiss this guy, because he's not from Chicago," but I am the grandson of two small town, Midwesterners that moved to Chicago, fell in love, got married, had my aunt before they move east and had my mom. My grandfather, at the end of his life lived with us for six and a half years. And even though it was 60 years ago, he talked incessantly about the city and his time here, it just, it was a formative moment for him in the 20s and 30s. And it was a rough time. I mean, I sometimes think about it, he kind of romanticized industrial Chicago in the 20s and 30s, you know, when Al Capone was in the headlines during the Depression. He famously told me stories about working as a night security guard at the World's Fair in 1933, shooting rats, among other things. And so he kind of planted a seed about the city for me, I found myself in the city while working on my my first book, "Power to the Poor" on the Poor People's Campaign, because you can't really understand Dr. King's Poor People's Campaign in '68 without getting a sense of the Chicago Freedom Movement two years before, and many of the things that they decide to do in terms of the coalition that they build, and some of the issues that they pursue, in '67, and '68, are shaped by the Chicago Freedom Movement experienced by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And so I came to Chicago, was digging around the archives, following the story of Al Raby, who was one of the people that invited Dr. King, in 1966, to have a campaign here. And then outright, he shows up 17 years later, as a campaign manager, precisely the second campaign manager for Harold Washington in 1983. And he writes, in one of the memos that I found in the Harold Washington Library, about how Harold's campaign and the coalition he was putting together was, in many ways a continuation, and a culmination of the Poor People's Campaign from the late 60s. That really struck me and ends up showing up in my epilogue of my first book, and then reappears in this book. But that really got me thinking, "I want to know more about Harold, and this moment." The third thing I would say is that I was wrapping up the first book and thinking about another project when Barack Obama was in the first couple of years of his presidency. And what I've found is some remarkable parallels between the experience that Harold had as mayor in Chicago and what President Obama had, as President, the remarkable kind of white supremacy that both men faced, the opposition to their agenda simply because they were Black men. It was very obvious that that was the reason for some of the opposition. And also, I think, a certain level of complacency that may have occurred when there was so much energy spent to elect Harold in '83, you know, in the primary, and then the general, and then again, for President Obama, in the in 2008. So much energy spent, there's a sigh of relief among many folks who were part of both campaigns. And then for many people, they just go back to work, they go back to their lives, right, raising their kids, their jobs, whatever they happen to be. And I noticed really some distinct parallels between that kind of, I mean, I hate to say complacency, but I feel like that's what it is. Where, "Oh, my guy is in power now. I don't have to worry so much. The store is being minded the way it should be. The policies I care about, the values I share I have are going to be you know are going to be looked over well." And what we find is, and this is a major argument of the book is that doesn't matter if you elect people unless you continue to keep them accountable, through grassroots organizing, keeping them sticking to the values and the promises that they made during the campaign, then it's very easy to slip away from those and not actually pursue the policies that folks ran on. And I think that you see that time and time again, on both sides, the both the right and the left. But I think it's particularly striking with these coalitions that are developed, that are very fragile, inherently, on the left, that then folks stop paying attention. And then all of a sudden, the, the forces of the status quo and an opposition end up stymieing most of the reform that the people were hoping for.

Kelly Therese Pollock 15:54

So I want to ask a little bit about sources, because I know you did some oral history for this project. And, of course, we're talking about 70s and 80s. So it's not that long ago, people are still around to talk to, but it's striking how many of those people are also still names in Chicago politics. So many names that come up in this book, I was like, "Oh, yes, that person is still on the city council," you know. So talk to me a little bit about that process of talking to these people about their memories of the time.

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 16:23

Yeah, no, a great question. And I will say actually, I'll be really candid. One of my regrets is probably not doing even more oral histories, right? I did a number with, you know, folks from like, Chuy Garcia, who at the time he wasn't a congressman, he was a county commissioner; Brenetta Howell Barrett, and Jacky Grimshaw; some folks that became academics like Nina Torres and Dick Simpson, who was an alderman at one time in the 70s, but then a political scientist at UIC, a number of other people. And yes, the oral histories were absolutely essential in filling in some of those, helping me understand some of the nuances of what was going on, Helen Shiller, of course. And you know, I really do like, it's funny. It reminds me of a conversation I had with a historian colleague of the 19th century, who said to me very bluntly, "Oh, I'm glad my sources don't talk back to me." And I always thought that was a bit of a cop out. I said, "No,I think it's, it's good," you know, because then they can, I've had a number of people, from my first book, say, "I learned a lot from your book, because my worldview was, in some ways, a little narrow. It's like it was my experience, but you put it into this context that I didn't always see." Right. And so they found it really fascinating. I hope I get the same kind of response from the folks in this book as well. But you know, the oral histories are absolutely essential. There are also of course, collections that are existing, like the HistoryMakers Digital Archive, which I had access to, when I was a fellow in the Black Metropolis Research Consortium. And I was able to spend time listening to those oral histories that they were absolutely essential with folks that are no longer with us, or just have forgotten so much that an oral history with that may not be as productive. But those oral histories are really, I think, essential, in under, in complementing the written sources, both Harold Washington administration's power, you know, all the paperwork that was produced by the administration, certainly the the local media, other commentaries. I mean, what one of the things about being a 20th century historian or a more modern historian is, there seems to always be something else I can look at. And there's a moment where I have to draw the line and say, "I think I have enough to do it, you know, to make the arguments I want to make." But it brings up another point that I would like to stress is that it was a balancing act in this book that I was really trying to strike, which was doing the Chicago story correctly, where people in Chicago would say, "Okay, he might be an outsider, but he actually knows what he's talking about." And getting enough of the details in there that folks care about some of the inside baseball, maybe even the folks care about and, and know, and will quiz me on if I didn't know, but also trying to make a national to really make a an argument about the national implications of this. I think it's important that that across the nation, people understand that while Chicago is a really unique place, the machine is quite unique in its power, at least at that time. That it's the other cities have similar experiences at to a certain extent that we can learn a lot from the Chicago story about understanding national politics, the limits of the Reagan, the Reagan Revolution, the alternative politics that happened in urban spaces like Chicago that, that really preview the Democratic Party of the 21st century, in many ways. So trying to balance that kind of Chicago story with with the national one that I think is very much there that is often overlooked. And it goes back to a question that you asked before, is that I really thought the story of Harold was was told, narrowly, and told too much through the lens of him as a person, the decline of the machine, and the kind of unity of the African American community in the city, all absolutely true. But I also thought that there were other aspects of this that are particularly important to understanding the 80s, politically, the rising Latino role in local politics, but also increasingly national politics that we see, as well as the role of the War on Drugs and crime and the limitations that even Black mayors have, in trying to control that without falling into the trap of mass incarceration, the AIDS crisis and the response to that; there's a lot of things that are going on in Chicago that are also going on in other cities, that I think that Chicago is a great vehicle to talk about both what happened here and, and give Chicago activists and Harold Washington their due, while also making some arguments about the national political scene.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:32

You mentioned in the book that you don't want this to be "the great man story." And that's very easy to do with Harold Washington, the same way it would be with Barack Obama. How do you strike that balance, then? Because he he was a very singular, once in a generation kind of politician. So how do you strike that balance of figuring out how much to emphasize what is unique about him versus this moment, that isn't just him?

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 21:58

Yeah, it's a great question. And I think I still struggle with it a little bit. And just when I when I talk about the book, and as I read the book, I you know, again, I'm like, yeah, it's, you could very easily I can see why people fall into the trap of no one could have done this but Harold. He was such a kind of a once in a generation leader in many ways in terms of his charisma, and its ability to walk into any room and charm people, even folks that were politically opposed to him. And that was something that was really striking about the '83 and '87 campaigns. But I think it's good to remember that, even though that might be the case, he would have lost without every member of that coalition showing up, without the more than 100,000 new voters registered in '82 and early, really in '82, in part for the 1982 congressional and statewide races. It wasn't clear if Harold was going to run. And so there's all this federal registration, all this kind of groundwork done by Lu Palmer, Slim Coleman,, Helen Shiller, all these folks on the ground and in different parts of the city that make it possible for him to succeed. Right. And I think that that's what I continue to stress is that Harold was able to take advantage of this moment because of all the work that people that we have heard of, in local politics since then, and many people that we have forgotten or haven't heard of, right, that made it possible. The first several chapters of the book, really decenters Harold. He's mentioned on occasion, as an early, you know, he's a, he's a member of the machine until the 70s. He's part of his ward organization. He's a state legislator in Springfield, every once in awhile strays from what the machine wants him to do. So he's always been a little bit more. He's always a little bit more independent. But he's pretty much a machine pol in many ways. And so what I'm sketching out in this first several chapters is what everyone else is doing, right? What Brenetta Howell Barrett is doing and the protest at the polls organization; the Chicago League of Negro Voters in the 50s that start running city wide folks for not mayor but for other other positions; the role of Ralph Metcalfe who breaks with the machine at least briefly over police brutality; Rudy Lozano, and then Chuy Garcia who really decide that Latinos, at least their kind of contingent of really progressive Latinos, need to get involved in electoral politics in the way they hadn't before. All of this sets up the moment for Harold to actually take advantage, but, you know, as someone told me early in this process, if it wasn't for A.) Incumbent Mayor Jane Byrne, who was quite unpopular, but had her support because she was an incumbent mayor, and Richard M. Daley, the boss's son, and the current, you know, at the time current State's Attorney, running against Harold in the Democratic primary in a three way race, two white candidates who had strong support, he doesn't win. If there's only one of them, he ends up losing to one of them, whoever it was, and it really took, there was some, so there's contingency as well. That's all to say that Harold, of course, is an incredibly important part of his story. And he shows up on the cover for a reason, he's in the title for a reason. But it doesn't happen without all these other people. And and I think that that's my first book, about the Poor People's Campaign, it happens, in part because of Dr. King, but also, because of all the people that pick up his mantle after he's assassinated and go forward. And so I think it's important for us to try to balance, give due and respect to these, you know, these kind of larger than life figures, but also kind of show how they're just, they're human beings. And they're not, they can't do it on their own. Right, they need a bunch of people around them.

Kelly Therese Pollock 26:11

So let's talk about the machine. What I find so fascinating about the Democratic machine in Chicago, is that even the people who are not in the machine, all come from the machine. There hasn't been a Chicago mayor in, you know, a century who wasn't somehow at some point part of the machine. So for people who are perhaps not as familiar with Chicago, what the heck is the machine? What what is this apparatus?

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 26:37

Wow, yes, you're right. It's striking how how powerful it is. And I think that that is, you know, there are machines and other cities, I think it's important to note, but none of them are, you know, they all pale a little bit in comparison to Chicago, the strength of the Chicago machine, which has changed over time, right. Really, the machine that I talked about in the book started in 1931, with Mayor Cermak, and of course, it was replacing what was not as strong of a machine, but a Republican machine, actually in the teens and 20s, under Mayor Thompson. It started in '31. It is it is really the Democratic party organization. And through patronage where from you know, both the alderman and the committeeman, who is of course, the most powerful figure, so a member of the Democratic Party Committee, or a Cook County Committee, they pretty much dole out favors, they will fix your sidewalks, they will fix the streetlights, they will make sure that zoning goes your way, as long as you promise to support them, in the next election. And it is a pretty well oiled machine, hence the word "machine," right where it works. And it worked for a remarkable length of time. Again, it's interesting because it sounds pretty conservative, and in many ways it is but of course, it also relies on infusions of federal money, the machine politicians from the 30s, 40s, 50s, and onward, it's especially Richard J. Daly, liked federal money, and liked a lot of it. And so they could build big projects. And they could dole that money out to all their supporters and all the folks that work in their machine organizations. And so that would be you know, that that was always the striking thing about Mayor Daley, for instance, is that he didn't fit exactly in what we would think of as the conservative liberal like pol of politics today, right? He liked a lot of federal, he was very conservative culturally, built neighborhood and ward based organizations to support him, gave them both city money and federal money that he controlled usually, to make sure that those loyalties remained. And, and so a big federal government that spends a lot of money like in the New Deal, totally fine, as long as he can control it. And I think that's where he starts running into problems in the late 60s, and that the War on Poverty and some of the other kinds of legislation and what money was going toward, like the maximum feasible participation in the poor. It's like, why would you give poor people the power to actually dictate where money is being spent? So this organization takes advantage of neighborhood ties, ethnic ties, oftentimes, which are the same thing right? The Irish neighborhood of Bridgeport, for instance, where those Daleys are from, that becomes very central to how the machine works, and the relationship with City Hall. In some ways, there are people that are better at talking about the heyday of the machine, because a lot of a lot of ways I talk about the how the machine falls apart, at least briefly or doesn't fall apart, maybe fall apart is overstating it. But but really, I write the core of my book is about the three elections where the machine loses in 1979, '83, and '87. And a lot of ways it really is. I mean, speaking of great man, right? I mean, one could argue that Richard J. Daley also has a great man kind of story that around him, that he was able to kind of keep this coalition his own coalition together, by controlling very closely the levers of power. I mean, he was by far the most powerful boss, and because he was not just the mayor of Chicago, but he also was the chair of the county party. And that was the key. No one had ever done that before. And no one has ever done it since. Even if the county chair is a close ally of the mayor, it's never been the same person. But it was under Richard J. Daly, between '55 and '76. And so that was even his son doesn't do that, right, in the 90s and 2000s. So, but yeah, it produces even there's three, there's two people that do beat the machine eventually, for the, in the mayor's race. Jane Byrne in 1979, you know, is a protege of Mayor Daley. And then when she gets kind of pushed out by the by his successor, she runs against him, calls them a cabal of evil men. But then, but as soon as she wins, she turns to them to help run the city. And then Harold Washington has a little bit, I mean, there's a little bit more of a legitimate anti machine candidate by '83. And then he really breaks with the machine in the 70s over police brutality and other issues and other civil rights issues. And so when he runs for mayor the first time in 1977, which a lot of people don't talk about, but as it was an important kind of test run, where many things didn't work. But he learned and his key, some key aides like Jacky Grimshaw and others learned, "Okay, if we run again, we have to actually build the coalition and not just talk about it." But he, yeah, but when he announces that he's running in '77 and breaks, that's a that's a clear break with a machine that he never, never tries to restore.

Kelly Therese Pollock 32:33

So I think one of the tensions then that happens is Harold Washington is elected, he has broken with the machine at this point. And he wants to make genuine reforms and does make genuine reforms. But some of the reforms he makes actually makes his supporters angry. So he gets rid of a lot of these patronage positions, which is great, that's a good thing. Let's, you know, tear down the machine, but then he doesn't have patronage positions to give people. So can you talk some about that tension? And what's going on there? And why it makes it difficult for anyone to make a reform in this system that you just won a seat in?

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 33:08

Yeah, no, that's a great question. And I think it's the part that has not been talked about very much, especially, I think much of the focus is, is on the racism of his opposition in the council wars, and, you know, led by Alderman Ed Vrdolyak and Ed Burke, who, of course, is still around with us, you know, finishing his career. But yeah, the fragility of his coalition is a really striking one, because there are inherent contradictions to it. And folks that ran, the people that had been against the machine for the longest time, for lack of a better term are like good government reformers, people that thought patronage was corrosive and corrupt, that paying to play, you know, doling out jobs to support people was just not the way you govern in a democracy, in a small "d," small "d" democracy. And so those folks are behind Harold. And they are some of the clearest independents throughout the 60s and 70s, white and Black. And so they you know, they have expectations of Harold when he becomes mayor, which he honors in many ways around transparency, opening up the budget process, opening up freedom of information, and also endorsing the Shakman decree, which really greatly reduced how patronage worked in the city. So let me I think it's it's one, it's good to note that, you know, there are 1000s of city jobs that were directly connected to patronage. But then there's also a lot of folks that are indirectly affected or get city money, or federal money through this through city mechanisms that are part of the patronage system. So it's not just 40,000 or 50,000 city jobs. It's all these other things. But the Shakman decree at least is saying that you can't just willfully fire and hire people without a process, shifting many positions from being strictly political positions to being something that has some quasi protection through the civil service in the city. And so Harold embraces that that reform. But at the same time, many of his supporters, including African Americans, like Lu Palmer, that I mentioned before, and other folks are like, well, we've been a junior partner in the machine for a very long time, or are cut out of it completely. Yes, there are Black aldermen, who will run their ward organizations, yes, they can dole out a certain amount of city jobs, they there's a certain amount of Black police officers and Black firefighters and Black teachers, etc. But now that we're in power, we really should get our full share that, you know, they, if you looked at the numbers, and I'm not gonna, I'm not gonna get all the numbers correct. So I'm gonna, I'm gonna stay in vague, using vague numbers here, but but their percentage of city contracts and city jobs never matched up to 1983, the number of African Americans the demographics in the city, which is, you know, roughly 40%. But contracts were in the teens or low 20s. Same with city jobs. So, whites always were over represented in the in the contracts that were given by the granted by the city. And in the jobs, whether it's in sanitation, or the Parks Service, which are two of the most notorious patronage agencies and many others. So when a Black mayor entered a city hall, or the fifth floor of City Hall, with their support, the expectation by many was like, "Awesome, we're going to start getting these jobs, and we're going to start getting these contracts." And while I would say that it's very clear that city contracts, affirmative action is start started to be used in some pretty clear ways by by Harold in the mid 80s. And so you start seeing a lot more African American workers and African American owned firms getting city business, it takes a while for that to happen, in part because the the patronage system is working out is working differently than it used to right. And Harold is very proud to say, you know, "I was elected by a coalition. I think the most important thing is not to do what the white dominated machine did, except the opposite. It's best to be fair, and I want to be known as a mayor who is fair to all." And some folks are like, "Are you kidding me? Do you, you came from the machine, you were born out of this machine, your dad was part of the machine, right? Even born and raised in Chicago. This is the way the game is played. If you win, you get some of the spoils." And there's a lot of grumbling among some of his supporters, both in city council and outside that say, "That is a missed opportunity. If you want to help. And I think this is an interesting argument, "If you want to help working class African Americans in the city, which you say you do, then you will give them jobs, that the kinds of jobs that white ethnic working class folks often got with no more merit than our folks had, or maybe less merit. And so we're missing an opportunity here to benefit the community, and the people that put them in power." So So you have these good government folks on one side who are cheering these efforts by Harold to open up the city in many ways. And then there's other folks who are like, "Well, no, I should get a job." And it wasn't just African Americans, I think it's important to know, there were many Latinos, you know, folks that were canvassing, pounding their beat, so to speak, with the hopes that, "Okay, I'm gonna get a job at the end of this," and many of them didn't, or they did, but it took several years for it to happen. And that was something new, I think, for this city in particular to, you know, for many folks, and it's like, this is not the way it's not the way business operates in Chicago. But it was very clear that Harold was like, shouldn't be business as usual. That's not the way small "d" democracy works. That's not the way I want to, you know, I want to run my administration. And yet, the other thing I would say, I guess, is that folks also didn't want to criticize the first Black mayor too much. Just like people didn't want to criticize the first Black president, I think Harold gets a lot of deference, because 1.) It's is much better than the alternative. But 2.) A lot of people respect him and think that eventually things will change. Maybe they're not happening as fast as we would like it to.

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:54

So let's talk a little bit about the council wars because that's part of the reason that things don't change as quickly as they could. And there is just some overt racism. They make no secret of the fact that they're just anti Harold. What is going on here?

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 40:10

A few things are going on here, right? I mean, this is the story of our of the nation, in many ways, is the fear of Black political power. And because, "Oh my God, if African Americans are in power," as Ed Vrdolyak, Ed Burke, and white ethnic folks would say, sometimes they would say it, sometimes they wouldn't. They actually said it a lot, though, pretty explicitly, "they're gonna do the same thing to us as we did to them." It's an acknowledgement of how unfair the system was, how much white supremacy kind of shaped public policy, whether it was housing or policing, or education or jobs, you know, development. All of this was shaped by protecting white investments in whatever it happened to be: your home, your local school, and the jobs that you fought for, by through patronage, for instance. And it's, and we see it in today's campaign as well, not to get into today too much, but, you know, there are code words now used, but many of the same arguments. And so, you know, Ed Vrdolyak, and that one of the most shocking sort of moments, or it's a couple moments, he is allied with Jane Byrne, the incumbent mayor, on the eve of the primary, he said, he basically says, to all the precinct captains, "We're fighting for the city the way it is. You don't want to let a Black mayor happen, because the city will change and not for the better." And then after Harold becomes mayor, Vrdolyak in what was kind of a shocking moment for the newspaper publishers that were in the room with him, he said, "So his goal Harold's goal," according to Vrdolyak was "to drive whites out of the city to make it Blacker, so he can win reelection." It's all about just power. Right? And who's going to control the spoils? Who is going to control the police department? Who's going to control the Housing Authority? Who's going to control parks and sanitation, all these things? And so, you know, they there really is, it is a, it is a fight over its differing visions of what the city should be. But it's incredibly racialized. And, you know, I think it's Chicago has a reputation in the rest of the country for being, but I think some people don't fully understand. And when they think of racism and segregation and racial polarization, they still think of Mississippi and Alabama first. But as Dr. King said, when he comes here in 1966, "I would take an Alabama racist any day because I least know where they stand." But it was having folks here like Mayor Daley talk out of both sides of his mouth, you know, saying, "Oh, yeah, I support civil rights," but not doing anything was worse, in some ways than the Klansmen in Alabama. So the council, you know, the, the way the council wars worked is, is Mayor Washington had 21 members of the council who were loyal to him. There were 29 opposed (28 white, and the one Latino that was on the council at that time.) And basically, over most things, appointments, budget, you name it, in terms of legislation, what Harold would put up, would go down 21 - 29 to defeat. An alternative was proposed that would win 29 - 21, but then be vetoed by Harold. And then you can't override a veto without 34 votes. And that happened over and over again. So if you look at he did make appointments, he had the power to make appointments, but they were all acting acting agency chiefs for the most part, right. And it wasn't until the special election in 1986 that changed the makeup of the city council to 25 - 25 that he was able to take many of the people that he had tapped in temporary positions and made them permanent at least permanent for another year and a half.

Kelly Therese Pollock 44:21

Alright, so let's talk about Harold Washington's legacy because I you know, I was not in Chicago during the Harold Washington years. But having lived here for a couple of decades now. You can't walk a block at least in Hyde Park without seeing Harold Washington something: Harold Washington Park there's a you know, plaque for him Harold Washington Library downtown, and as far as I can tell, he's just universally beloved. Everyone thinks he's the greatest mayor that ever happened in Chicago. But clearly that wasn't always the case when he was in power. So how did he get this outsized legacy?

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 44:55

Well it's like anybody who is cut down in you know the prime of their power in some ways and influence. So he was 65 when he, when he died. So he wasn't Martin Luther King. He wasn't Malcolm X. He wasn't John F. Kennedy in terms of being a younger man, where it seemed like there was so much, you know, "Oh, what would have happened for the 40 years after this, you know, if this gentleman had lived?" But there is something about the what ifs. And I, you know, I don't want to spend too much time as an historian at least talking about what if he had lived and what would have happened? Because it's just not clear. Right? It could have gone in many different directions, in terms of the kinds of reform that he was pursuing. But I mean, I definitely think that that's a powerful part of it, right? Somebody who dies in office, with so much more with so much potential that way that seems unfulfilled, and you know, here at Hyde Park, at least, he was he lived here, right? So he was he was part of this neighborhood. So it's not surprising there's a lot of things named after him here. The library project was underway during his administration when he was, you know, when he died, and he was a really educated, well-read, man. So to name the main library after him makes a lot of sense. But it doesn't benefit anybody, including Richard M. Daley, to trash Harold Washington after his death. It doesn't make a whole lot of sense to do so. I mean, there's certainly some people that are critical of him behind the scenes, but they were able to take some of the things that he did, and, and turn them to their own, to their own benefit in many ways. One of the interesting legacies of Harold's administration was the empowerment of Latinos. Of course, they did a lot of that themselves, building organizations, just demographic shifting in the city, but he championrd Latino issues throughout his administration, in terms of Latino majority council or wards basically in remapping. He was supportive of the first Latino majority congressional district in the city, that he doesn't live to see, but occurs in the 90s, after the census. He makes Chicago an early sanctuary city, for immigrants who are fleeing Central America in particular, and the violence, there, violence, that of that US foreign policy actually made worse, in many ways. He, he did all these things that really mainstream Latino politicians and Latino issues in the city, that that Eugene Sawyer, and particularly Richard M. Daley couldn't undo. And so what's interesting about Daley in the 90s, is that he has his own Mayor's Commission for Latino Affairs. The people on it are different. They're more businessmen, they're more conservative, they're more middle class. They're not Chuy Garcia and Linda Coronado and Nina Torres, Miguel Davila . It's a different group of folks. But Latinos become an incredibly important sort of political force in the city, that often, you know, at least some people would say, offer the swing vote sometimes, but for who wins city wide office. So I mean, I think that's one of the legacies. He also, Helen Shiller would say that he opened up the budget process in a way that is never, you know, that may was maintained, you know, well after his death. It doesn't mean that scandals don't happen. And there were plenty of scandals under Mayor Daley, the second Mayor Daley, but there were, it was hard to roll back. the way patronage, Mayor Daley, the second Mayor Daley couldn't roll back patronage back to how his dad did it. And this looked, it looked quite different. It's something that we would call pinstripe patronage. Right. So less about city jobs, working class city jobs, and more about giving city money to lawyers and accounting firms, you know, that are aligned with with Daley and his friends. But but, you know, he does, he left a stamp on the city of what could be, you know, and as many folks, you know, kind of just talk about the 80s as this moment of promise and possibility that went unfulfilled. And maybe that could happen again, right? It hasn't happened again. But it's it's been kind of romanticized that way. And it's one of the, you know, again, it goes back to one of the reasons why I wanted to revisit this. I think that mythologizing the era a little too much is is is dangerous, just like we shouldn't mythologize Dr. King or any other individuals, right, from our past. Humanizing them, recognizing that they had their faults empowers us now, because otherwise, you know, we don't think of ourselves as, as being worthy to be historical actors, right? And I tell my students, anybody in this room can be an historical actor that we talk about 10, 20, 50, 100 years later, because that's what those individuals were that we talked about now. They're just human beings. So making them folk heroes isn't always that productive, as much as I love Harold. And I call him by his first name, because that's what everyone does here. And I understand it. You know, I remember him as an 11 year old bizarrely. I was living in Baltimore as a kid, you know, but I remember when he was elected. I didn't, I was already kind of interested in politics, and I didn't know anything much beyond that. But I remember when he was elected very strict, you know, I don't remember the council wars as much, but it's, uh, yeah, I mean, I hope, you know, this work does that era justice, but also in a clear eyed way, that I would argue maybe only an outsider can do. A bunch of Chicagoans would disagree with me on that, I'm sure.

Kelly Therese Pollock 51:11

All right. Well, so we don't talk Chicago politics all day, which I'm sure I could do. Just tell everyone how to get this book.

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 51:17

Oh, it's available anywhere. So you can do it on Amazon, of course. But you can also go to the University of North Carolina Press site. If you have a favorite local bookstore, you can also order it through there.

Kelly Therese Pollock 51:31

Excellent. Gordon, thank you so much. This was so fun.

Dr. Gordon K. Mantler 51:33

This was great. Thank you.

Teddy 51:34

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode, and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on twitter or instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Dr. Gordon Mantler is Executive Director of the University Writing Program and Associate Professor of Writing and of History at the George Washington University. He specializes in the history and rhetoric of 20th-century U.S. social justice movements, multiracial coalitions, public history, memorialization, and film, and writing pedagogy in history classes. His first book, Power to the Poor: Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economic Justice, 1960-1974, was the inaugural volume in the Justice, Power, and Politics series at the University of North Carolina Press in 2013. His current book, The Multiracial Promise, is due out in winter 2023 with UNC Press and focuses on multiracial electoral politics and community organizing in Chicago in the 1970s and 1980s. He has received numerous awards, including the first annual Ronald T. and Gayla D. Farrar Media and Civil Rights History Award for the best article on the subject. His work has been supported by GW, Duke University, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Humanities Center, the Black Metropolis Research Consortium, and the Lyndon Johnson Presidential Library.