Gladys Bentley

One of the biggest stars in Prohibition Age New York was blues singer Gladys Bentley, who caused a stir in Harlem, wearing a top hat and tails, flirting with women in the audience, and singing raunchy lyrics. Despite Bentley’s phenomenal talent, the repeal of Prohibition and the end of the jazz age led to waning interest in the type of bawdy performance for which she was known. Despite attempts to change with the times, Bentley was never again able to reach the level of fame she had once enjoyed.

Joining me in this episode to discuss Gladys Bentley and queer Black women performers in Prohibition Age New York is Dr. Cookie Woolner, Associate Professor of History at the University of Memphis and author of The Famous Lady Lovers: Black Women and Queer Desire before Stonewall.

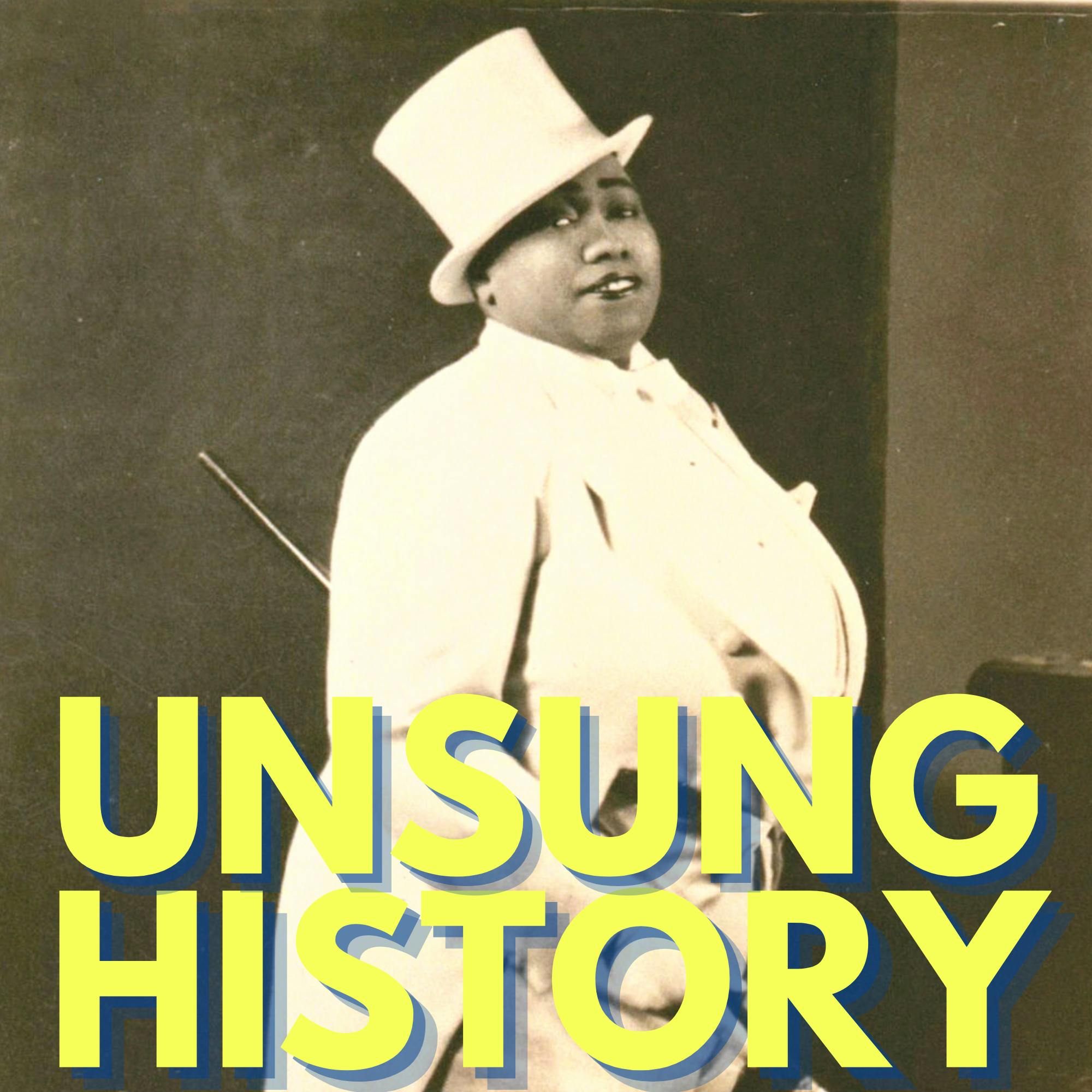

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “Them There Eyes,” performed by Gladys Bentley on You Bet Your Life on May 15, 1958. The episode image is a photo of Gladys Bentley on a card distributed by the Harry Walker Agency, with a caption that reads: “America's Greatest Sepia Player -- Brown Bomber of Sophisticated Songs;” the photo is in the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and is in the public domain.

Additional Sources:

- “I am Woman Again,” by Gladys Bentley, Ebony Magazine, August 1952.

- “Gladys Bentley: Gender-Bending Performer and Musician [video],” PBS American Masters Unladylike2020, June 2, 2020.

- “The Great Blues Singer Gladys Bentley Broke All the Rules,” by Haleema Shah, Smithsonian Magazine, March 14, 2019.

- “Overlooked – Gladys Bentley,” by Giovanni Russonello, The New York Times, 2019.

- “Honoring Notorious Gladys Bentley,” by Irene Monroe, HuffPost, Posted April 14, 2010 and updated May 25, 2011.

- “Blues Singer Gladys Bentley Broke Ground With Marriage to a Woman in 1931,” by Steven J. Niven, The Root, February 11, 2015.

- “Gladys Bentley on ‘You Bet Your Life’ [video],” Aired on May 15, 1958; posted on YouTube by Joel Chaidez on December 18, 2009.

- “Gladys Bentley (feat. Eddie Lang) How Much Can I Stand? (1928) [video],” Audio recorded on November 2, 1928 and issued as a single by OKeh in 1929; posted on YouTube by randomandrare on April 16, 2010.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. On this episode, we're discussing a legendary blues singer and pianist of the Harlem Renaissance, Gladys Bentley. Gladys Alberta Bentley, was born on August 12, 1907, in Philadelphia, the oldest of four children. She described her childhood as difficult. From an early age, Bentley rebelled against societal norms, wearing her brother's clothing, and developing crushes on women. Bentley's parents disapproved of her behavior, and sent her to doctors to try to fix her. At age 16, Bentley ran away, leaving Philadelphia for New York City, where she started performing at rent parties, private apartment parties with alcohol, flaunting prohibition, in which the hosts charged for admission. Bentley heard that Mad House on 133rd Street, was looking for a pianist, and she jumped at the opportunity, convincing the manager to give her a chance, even though they had been looking for a boy to play. They were so impressed by her talent that she was offered the gig, making $35 a week to start, which was quickly upped to $125 a week, plus tips as she brought in white patrons eager to see her perform, dressed as she later described, in, "white full dress shirts with stiff collars, small bow ties and skirts, Oxfords, short Eton jackets and hair cut straight back." In August, 1928, Bentley signed a contract with Okeh Records for eight record sides, which included the songs, "Worried Blues," and "How Much Can I Stand?" Bentley became a hit at Harlem venues like the Cotton Club, that featured Black performers, but all white audiences, who thrilled at the titillation of seeing a Black woman, dressed like a man, singing raunchy lyrics to popular songs. Bentley's sexual orientation was no secret. She regularly flirted with women in the audience at her shows, and in 1931, she revealed to a gossip columnist that she had recently married a white woman in New Jersey. The identity of the woman is unknown. As Bentley's fame grew, she moved her act from Harlem to Broadway, where she performed in tailor made top hat and tails. The more mainstream crowds were less enamored with Bentley's baudy performances though, and complaints led to police locking the doors of the venue where she was set to perform. In 1934, Bentley moved her act back to Harlem, to the infamous Ubangi Club, where she was a main attraction for the next three years, performing with male backup dancers dressed in drag. At the height of her popularity, Bentley lived on Park Avenue in a fancy apartment, where she was taken care of by servants. Langston Hughes wrote of Bentley, "For two or three amazing years, Miss Bentley sat and played piano all night long, with scarcely a break between the notes, sliding from one song to another, with a powerful and continuous under beat of jungle rhythm. Miss Bentley was an amazing exhibition of musical energy, a large, dark, masculine lady whose feet pounded the floor, while her fingers pounded the keyboard, a perfect piece of African sculpture animated by her own rhythm." Photographer and writer, Carl Van Vechten, who saw her perform, took Bentley's photo several times and used her as the inspiration for a blues singer in a novel with the description, "When she pounds the piano, the dawn comes up like thunder." However, with the repeal of prohibition, and the end of the Jazz Age, the public's appetite for raunchy performances like Bentley's waned. In 1937, Bentley left New York, and headed to California, where she performed in Los Angeles and San Francisco with a toned down act, compared to her Harlem days. In 1945, she recorded sides again, this time with Excelsior Records, including the songs, "Red Beans and Rice Blues," and "Notoriety Papa." With the more repressive social milieu of the 1950s, Bentley ditched her masculine attire in favor of women's clothing. In August, 1952, she published an essay in Ebony Magazine, titled, "I Am a Woman Again," in which she wrote that despite her fame, she had been lonely, saying, "Today, I am a woman again, through the miracle which took place not only in my mind and heart, when I found a man I could love and who would love me, but also in my body, when the magic of modern medicine made it possible for me to have treatment, which changed my life completely." In the piece, she said she'd been married to a man named, Don, and was at that point remarried, to columnist JT Gibson. However, after the Ebony piece came out, Gibson denied that they had been married. Later in 1952, Bentley married a cook named Charles Roberts, in Santa Barbara, after what was described as a whirlwind courtship. In 1958, in the only video we still have of Bentley, she appeared on Groucho Marx's game show, "You Bet Your Life," where she played the piano and sang. By 1960, Bentley, who was living in California with her mother, had become a member of the Temple of Love in Christ's Church, where she was studying for ordination. Sadly, she died suddenly of pneumonia on January 18 of that year, at the age of only 52. She's buried in Carson, California, next to her mother. Joining me now to discuss Gladys Bentley and other queer Black women performers in Prohibition Age New York is Dr. Cookie Woolner, Associate Professor of History at the University of Memphis and the author of, "The Famous Lady Lovers: Black Women and Queer Desire Before Stonewall." First though, here's a clip of Bentley's performance on "You Bet Your Life," where she sang "Them There Eyes," a jazz standard that had been made famous by Billie Holiday.

Hi, Cookie. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Cookie Woolner 10:04

Thanks for having me. I'm happy to be here.

Kelly Therese Pollock 10:06

Yeah, so I'm excited to talk about Gladys Bentley. Before we get into that, I want to hear a little bit about how you came to write the book that you did, how you got interested in this topic.

Dr. Cookie Woolner 10:19

Yes, I actually discovered the classic blues women, women such as Bessie Smith, and Ma Rainey. I learned about Gladys Bentley a little bit later. But um, I discovered them in my undergrad studies, I was kind of doing some early work in what we probably now consider to be Fat Studies, and I was really blown away learning about these larger women who sang these songs about real kind of their unabashed desires, um, you know, as a, as kind of a shy, non confident chubby teenager, I was just kind of flabbergasted by them, they kind of became my, my new heroes. And then later, I learned that some of them were queer. And then when I started my PhD program, I was pretty sure I wanted to focus on queer women's history. So it kind of just became this, this obvious fit. And then I learned about somebody like Gladys Bentley, who blew me away even more, because, as one would probably expect for, you know, 100 years ago, most of the blues women, they still as they became celebrities, especially because of their celebrity status, they, you know, often were trying to kind of appear, you know, respectable in public or not doing anything too scandalous because they were concerned about their reputations. But somebody like Gladys Bentley really just did not care what people thought. She really put it out there. She's someone who we kind of often think of now as a drag king or male impersonator, but she was really just being herself, she wasn't trying to kind of perform in a male persona. Um, she was also large and masculine. And so she becomes an interesting figure in terms of drag when drag is often focused on, um, drag queens often, you know, very, very kind of thin white drag queens especially. So the fact that she was seen as such a subaltern figure, but she really kind of became, in some ways, kind of the center of like prohibition culture, and Harlem culture in the late 1920s is just really fascinating. So she's definitely one of the one of the boldest women in my book, which focuses on Black queer women in the 20s and 30s.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:04

Yeah, I wanted to ask too, about the title and a little bit about terminology. So you talk about Black lady lovers. And I know, it's difficult when you're talking about anything to do with homosexuality or queer studies over time, because the terminology itself changes over the course of the 19th and 20th century. So can you talk a little bit about why you titled the book the way you did, what you're thinking about in terms of terminology?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 12:31

Definitely, you know, it's a great question. And it always is a bit of a sticky subject, because, you know, we often want to use more kind of contemporary terms, as opposed to historical terms, especially when you know, the historical terms start to feel sometimes antiquated. So I came across many references to women who loved women in the 20s and 30s, being referred to as lady lovers or as women lovers. And there's one specific quote, the quote, that refers to the famous lady lovers came from a Black female performer who was interviewed for a book about, um, Josephine Baker's life specifically. And she she finished because it goes on to say, you know, we were known as the famous lady lovers. Today, people would probably call us bisexual, you know, we're often having relationships with men and having relationships with women. So meaning that fluidity, sexual fluidity is a really big part of the book. And so I think, you know, more contemporary word like queer really kind of gestures to that fluidity. But I also have come across references going back to not so much the 20s, but the early 30s of women identify self identifying as queer. I found some of those references in archives in Chicago, for example. So it wasn't used too often as a self identifier at that time. And of course, no one was yet really using a term like lesbian. That comes more into the the post World War II era. And it's also of course, hard to find terminology that women actually self identified with. I have one chapter in the book that focuses on college educated women who left more sources aside, but of course, doing Black queer women's history, you know, is always a struggle of the dearth of sources. So it's hard to find out how women actually specifically kind of, you know, identified their own identities and desires, but I found that lady lovers was used enough in the 1920s, especially in the Black press, that that felt like a solid choice to use for the title. And then it also very specifically refers not to queer women, but to queer desire, so I didn't want to kind of refer to them as queer in in the title itself, even though I often do do refer to them as such in the book kind of just for the sake of ease.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:22

So you mentioned dearth of sources. That's often something we talked about on this podcast with all sorts of topics, but especially the more marginalized identities someone has, the more likely it is that those sources are harder to find that you need to do a bit of reading against the grain. Can you talk a little bit about, in general, the kinds of sources you looked at? And then when we think about Gladys Bentley, what are the kinds of things that we have about her life?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 14:48

Definitely. Yes. So definitely using articles from the Black press, you know, whether we're talking about the more well known papers like the "Chicago Defender," or really amazing kind of very gossipy New York papers that are mostly still on microfilm like the "Interstate Tattler," those were an incredible important source. Oftentimes, they would give a lot of you know details about specific events and I could find more information about them. Many blues songs were actually written by the women themselves, they weren't always but sometimes they were. And of course, they weren't often necessarily referring to their own specific desires. But you know, you could maybe kind of read into them that way. A few women, blues singers, such as Alberta Hunter have written biography, so there are a few autobiographies and memoirs as well. And then there's also other types of sources that I would use such as kind of vice records by vice organizations like the Committee of 14 that were created to kind of, you know, to stamp out vice in the, in the Prohibition Era, um, they're going, they're sending vice agents. And by the late 20s, they're finally sending Black male vice agents into spaces in Harlem and trying to find mostly prostitution, but they're coming across queer gatherings and writing detailed notes about them. So it's mostly unfortunately, you know, with the exception of the few memoirs and such, it's, it's still mostly kind of outsider sources, right? So you're always trying, again, that reading against the grain becomes very, very prevalent, you know, using mining sources for information that they like finding an article that's talking about, you know, violence between women at a at a rent party, and using it to kind of chart these women's, you know, social circles, for example. Obviously, that's not why that article was written, but I'm able to kind of mine it for these important details.

Kelly Therese Pollock 16:26

So you just used the term rent party, and that's where I want to go next is to talk about rent parties, buffet parties, what is this? What's going on? And this is in the, like, 20s ish in the urban north? Is that what we're talking about here?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 16:40

Yes, yes. So we're talking about, you know, kind of, we often refer to the 20s as the Jazz Age, and then the Prohibition Era is, you know, overlapping with that 1920sto 1933. So in this time, when it's illegal to purchase alcohol, we of course, have the emergence of all these illicit spaces. Some of them are speakeasies, some of them are even less known spaces, such as buffet flats, which were often run by very entrepreneurial Black women who had sometimes been sex workers or madams or entertainers themselves. And they're, they're kind of like private parties, but they would often have you know, different types of entertainers there. This is a place where lesser known blue singers could come and you know, kind of work on their new material, other types of illicit activities. One important thing about the Prohibition Era, is even though it's seems kind of this, like repressive time, in which you know, alcohol is banned, but everyone really, most Americans really hate this fact. And so they're really kind of bonding together over it, and then realizing that they kind of it's exhilarating to kind of, you know, break these taboos and go out and have some bootleg alcohol. So they might take part in some other illicit activity, right? Whether it's, you know, interracial dancing, or flirtation or, or queer dancing or flirtation. So kind of, you know, this kind of anything goes spirit is, is kind of taking the day here. But of course, it's also in this very, still very repressive time. It's a conservative era politically, it's still the Jim Crow era. Gladys Bentley herself becomes a symbol of kind of, of slumming. And so we have all these white middle class folks living, you know, in Midtown, or in the suburbs, who are reading about these prohibitions spaces, and they're coming into the spaces to experiment.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:13

So Gladys Bentley then comes out of this period, this is where she really rises to fame, or at least the level of fame that she had. So can you talk a little bit about that? Why, why this particular moment? And this, you know, sort of people wanting to rebel against the strict laws, that sort of thing, how that leads to her having this ability to come on to the scene and and really be what, what people are looking for.

Dr. Cookie Woolner 18:45

Yes, I guess one other very important historical event that starts a little bit before this, but that's crucial to this in answering your question would also be the Great Migration, right? So beginning in World War I, we have this mass migration of Southern African Americans to northern and western cities. And so this is when Harlem begins to become kind of the this kind of international Black Mecca. And we have the beginning of the Harlem Renaissance, and all this amazing art is coming out of Harlem, and Chicago and other urban sites. And so for somebody like Gladys Bentley, who grew up in Philadelphia, and, you know, it was obvious from a pretty young age that she was queer. And this is something her parents were not happy with. And they were actually trying to take her to a doctor to, you know, convert her to a good feminine, heterosexual, and she runs away from home and of course, the place she wants to go is Harlem because it's 1923 and that would be the place to be, so kind of because of the beginnings of the prohibition culture, but I'd say more so because Harlem has become kind of a Black Mecca at this time. It's, it's where you know, a young talented performer such as herself would want to go to, and so she goes and starts playing right away, and she's an incredible talent. We only have this one video known that you can find of her playing in 1958 actually on a Marx Brothers game show. She does this incredible piano number and you can kind of get an idea of the extent of her talent and imagine what she was like, you know, even 30 years earlier. So you know, right away people are, you know, incredibly blown away by her talent. And they might not necessarily be excited about her appearance, which is going to be you know, rather gender transgressive. But you know, she's because of her talent, she's kind of still welcomed into this, this world of entertainment at this young age.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:30

There's a certain appeal at this time period of you know, somebody who's pushing the boundaries and transgressing, but you write about the other Black women, the blues singers at this time, who are also queer, but are are hiding it a little bit more and Gladys Bentley is not. Can you talk a little bit about that and, and the ways that she is really pushing the envelope further than even the other entertainers at the time?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 20:55

Definitely, yeah, I mean, this in several ways, of course, firstly, the fact that she, you know, she would wear a very dashing tuxedo and tap top hat on stage, when she performed. She was known for going out into the audience and flirting with all the women in the audience and you know, at the space that she's performing in Harlem, these are also spaces where they're really welcoming, you know, white audience members and Black people are really only there work working behind the scenes. Unfortunately, even in Harlem, we're still seeing this, this kind of ongoing segregation at the time, especially when it comes to the entertainment world. So she's, you know, flirting with white women in the audience. She sometimes would sing, kind of take a popular song or two and kind of mash them together and write a dirty version of it. So she'd sing these dirty songs that people like kind of knew that sounded somewhat familiar that they can sing along with. And then kind of most outrageously, although we unfortunately, we don't have a lot of details on it, she told a popular white theatrical columnist that she was getting married in Atlantic City to another woman who was a performer, and all we know is that she was a white woman who was also a performer, but her identity is unfortunately, unknown. So um, so yeah, she had a had a queer wedding ceremony in this in this era, you know, to top it off, so she was definitely, definitely, you know, incredibly bold and brave for her era.

Kelly Therese Pollock 22:12

So she starts with performing for Black audiences, and then she's performing for these white audiences, but in Harlem, so in a place where people are sort of seeking out that this kind of entertainment. What happens then as she gets more popular?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 22:28

I mean, she gets so popular that clubs are named after her, you know, not like forever, but like, temporarily, let me that's kind of like the height of her performance. And then she's actually able to, because of the success in Harlem, she's able to perform kind of in more mainstream Midtown spaces for white middle class audiences. But these are audiences that weren't necessarily like seeking out like the wild prohibition antics. And this is where unfortunately, her act was seen as kind of too much. But then this is also happening around kind of the end of prohibition. And so now we have these kinds of like New Deal reform impulses to kind of clean up entertainment. So you know, there was one time where she was playing at a fancy Midtown club, and she was, you know, basically, they said that they locked the doors of a club, you know, she was barred from performing there because of her, her outrageously dirty lyrics, you know, according to the police. So, so yeah, she basically kind of met her end of her popularity, in some ways, kind of through New Deal reform, which is pretty interesting. But yeah, also, by the end of prohibition, a lot of people kind of claimed that they were just really kind of getting tired of like the, you know, all the excesses of, of the of the prohibition era, you know, it was kind of time to time to clean things up. And of course, you know, if it's time to kind of clean things up, that's not going to, unfortunately, go go well, for a performer known for, you know, doing kind of outrageous and somewhat sexual performances.

Kelly Therese Pollock 23:46

How were how was mainstream Black culture responding to her? You know, was she accepted? Were people not liking her? What, you know, what, what did that look like?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 23:59

Well, we do have a few, a few Harlem Renaissance writers, you know, probably one of the most famous ones would be somebody like Langston Hughes, and he does seem to be a bit exceptional, because he loved Gladys Bentley, and he loved Bessie Smith. And you know, he thought they were just kind of like amazing folk culture icons. But unfortunately, not too many other middle class African Americans really seem to kind of share, share that sentiment. It was more common for people to kind of see her as someone who was you know, putting forth a really bad representation of life in Harlem. And this isn't a quote specifically about her, but I think it kind of gets to the gist of it here. WEB DuBois wrote in his magazine, "The Crisis," at the height of the slumming vogue in 1927, "White people must be made to remember that Harlem is not merely exotic, it is human. It is not a spectacle and entertainment, it is life. It is not chiefly cabarets is chiefly homes." So we know very much kind of trying to remind people that you know, Harlem is a place where you know everyday people live also. This is because of racial segregation, right, which was not be, you know, legal in the north, but of course, it's still being practiced. And Harlem is one of only a couple of neighborhoods that African Americans are able to rent apartments in at all. And so it also becomes this displaced neighborhood at the same time, right? So this is something that's, you know, very troublesome to folks like DuBois. And so they want to kind of remind people that it's not just about, you know, coming there to see the entertainment or a wild night out. Like this is where people live their lives. So you know, because of that, she was seen as someone who, you know, many, many did not champion and saw as you know, putting forth a bad, bad image of African American life in Harlem.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:35

So you said, we get to the end of prohibition, and people are trying to clean things up and you know, her her popularity wanes. Do we know much about what happened to her over the next decade or two? You know, it seems like she sort of just fell off the map.

Dr. Cookie Woolner 25:50

Yes, she actually, well, she falls off the New York map. She heads west. Her mother had lived in California, and so she heads out there in 1937. And in the late 1930s, and early 1940s, like during World War II, she's actually quite popular in some of the early career women's bars and clubs that are appearing in places like Los Angeles, and San Francisco, especially. She's a popular performer at Mona's, which is a really fabulous, really lesbian bar in San Francisco. So she's able to still kind of do her act then. But I think she still at that time does maybe get arrested a couple times for male impersonation, or that might have come a little bit later, since, you know, most states but especially California, California, actually had one of the very first anti cross dressing laws passed in the mid 19th century. So there's these laws on the books where people can be arrested for something as innocuous as drag. Obviously, this is something that's um, unfortunately, still still relevant today. So that in the post World War II era, we enter into the Cold War. And so we have this new conservative era. And not only do we have what becomes of course, known as you know, the Red Scare with the rise of McCarthyism in 1950, but we also have this parallel of Lavender Scare where specifically gay people are being booted out of the federal government, right. This up in a association of queer people, basically queer people and communists, you know, they're out there the same thing. They're both, you know, subversive, they're disloyal. And gay people especially, are always in the closet, so they could easily be blackmailed. So they can't be trusted, right? So we have all this new kind of anti gay sentiment, not that anti gay sentiment in general was new, but kind of this new version of this new horrible strain of it, right in this post World War II era. And so it seems as if this just general sentiment is affecting Gladys Bentley, because in 1952, she writes this article for Ebony Magazine called, "I Am Woman Again," where she basically, you know, she doesn't necessarily like refute her past life. She seems to have a lot of sympathy for herself. She talks a lot about, you know, her difficult childhood and how she wasn't loved and accepted as a child, and how this, you know, led her to become aggressive. She uses that word specifically, which I find interesting. But you know, through medical help, and it's specifically through the use of hormones, she's now a woman again, she's feminine, she's heterosexual, she's married. The article includes images of her like doing domestic chores, like cooking for her husband and choosing her outfit for the next day. So it's very much seen, you know, you I don't think you can look at this article outside of the context of the Lavender Scare in this, you know, post World War II repression.

Kelly Therese Pollock 28:23

Was she unique in that? Were there other people doing this kind of transformation that we know of?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 28:28

That's a great question. I mean, it's quite common for, you know, women who are, you know, successful blues women to kind of often kind of become born again and get involved in the church later in life, that happened quite often. And that seems to be kind of a route that she took a little bit as well. If you read her obituary, it talks a lot about her involvement in the church and the last few years of her life. I mean, it just seems to be you know, connected to just, you know, wanting, wanting to be respected and loved, right, and wanting to put forth a, you know, a respectable image that people would want to want to care for and acknowledge really.

Kelly Therese Pollock 29:03

So you mentioned we have just this one video clip of her. Could you talk about this, this game show appearance that she did?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 29:10

Yes. Okay. So I think okay, so it's, it's one of them. It's one of the Marx Brothers. I believe it's Groucho Marx, I think it's "Bet Your Life." And so she she comes, you can find it easily on YouTube, on YouTube, if you search for Gladys Bentley. And she's, you know, she's a large middle aged woman, she she looks beautiful. She has like, she has a hat on and a dress on and she comes out, and she starts playing the piano. And then she tells her name to to the host. And he was like, "Oh, you're the Gladys Bentley. Like I thought you I thought that sounded familiar, right?" Because she has a different look at this time than the look people knew her having before. You know, she has a more of a more feminine look. And this is a few years after she wrote that article. But I mean, she's, you can just watch her hands like gliding across the piano. I mean, she's just so masterful, and she's, she's so talented. And they just, you know, they just have a little bit of a witty repartee. They exchanged a few words, isn't there's not a lot of substance to it really. But it's just It's our only chance we have to see her. So it's it's definitely worth seeing.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:09

Yeah. Do you think, she died not that long after that, sadly. Do you think she might have been able to sort of change and you know, have that more respectable kind of career if she had lived longer?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 30:21

That's a good question. Yeah. It's, it's hard for me to say I also am also one of those people, unfortunately, like, my specialty is earlier. So I don't actually know about her life a little bit later on, really. Yeah. I mean, it's also what's also interesting to me is that it's not like there weren't, you know, gay bars and drag performances in the 1950s. We have many, many documents of them. And there's many articles actually in an Ebony and Jet magazine, kind of talking about queer life, drag performance for for African Americans at this time, which is pretty fascinating. I'm just thinking, you know, we have figures, you know, this is, of course, the time of the rise of figures, such as Little Richard, right, who's going to kind of come of age, doing drag and in kind of vaudeville shows, as well. And we have this really long, rich history of drag and kind of more mainstream performances in blackface minstrely performance and vaudeville, and it doesn't really become seen as kind of queer until we get into the to the early 20th century. So I mean, we do have other, you know, examples of, you know, queer visibility in the 1950s. So it is interesting, why she specifically, you know, felt that she had to go the opposite route.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:27

Why do you think it is that we don't know more about her? I mean, you know, until I read your book, I had never heard of Gladys Bentley. And so you know, but she clearly was wildly talented, was famous in her time. Why is it then that someone like that sort of becomes somewhat forgotten?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 31:44

Yeah. No, it is interesting, because if you look at you know, her career parallel to somebody like Bessie Smith, I mean, they, they had quite a quite a few things in common. And yet someone like Bessie Smith was, we associate her so much more with kind of, you know, the blues, the explosion of blues records, and you know, which were at the time known as race records, and then touring the country nonstop, and selling, you know, hundreds of 1000s of records. And Bentley did record some records. But I mean, actually, it's interesting, because the songs she recorded, were never specifically queer. But it is interesting, because a few of them actually talk a lot about domestic violence specifically, like in heterosexual relationships. So I actually see them as very, very feminist, but they, you know, they weren't specifically queer. And this wasn't at a time when people were often recording and selling like super outrageous songs like the most kind of outrageously explicit queer songs would be, for example, such as, "Shave 'em Dry," by Lucille Bogan. We have recordings of it, but it wasn't like sold as a record. I'm not even sure why we have the recordings. But I don't know, part of me thinks that if she was able to record kind of more of her outrageous songs, maybe she would have been more well known. I mean, I think it's because she became successful in such such a liminal spaces, right. My mentor, Kevin Mumford refers to them as "inter zones," right, kind of like the most inter areas of kind of urban centers, um, spaces that often weren't like legal or commercial spaces, and, you know, very kind of like ephemeral performances that weren't recorded. I think that's probably part of the reason and also just because she occupied, you know, kind of so many marginalized identities at once, right? I mean, being Black, being queer, being fat, being masculine, you know, she wasn't someone who was held up, I mean, I'm sure she was to, to some of the women of the audience be there, she wasn't held up to like, you know, the mainstream as kind of, you know, anything similar to kind of like, you know, a movie star, in terms of, you know, being some people saw as a heartthrob or something. I don't know, I think it might be just the kind of, yeah, she was seen as kind of on the outskirts of society. But she was able to kind of be at the center of the world in this in this brief moment in the late 1920s and early 30s. And I think it's really, really fascinating how she became like, such a symbol of the prohibition era, even if it's not everybody was happy that she became that symbol. But, you know, I think she was really an important one. And she did so much to just kind of put forth queer visibility in a time when that was, you know, something that wasn't new per se, but was becoming a little bit more new in the in the mainstream. There was a, there was a couple plays about lesbianism that are first going on and Broadway in the 1920s and in 1926, this variety theatre critic writes about it and basically introduces the concept of lesbianism assuming that like the readers have never heard of the idea of two women being together. So really, this is the decade in which it seems that you know, to, I'm not sure, you know, to these, who are these people who've like never thought of this concept, but apparently to the some of them, so this was seen as something new at the time. And she became kind of a symbol for it, which you know, makes her truly iconic for, you know, for queer history, at least.

Kelly Therese Pollock 34:48

Yeah. So your book, of course, talks about more than just Gladys Bentley. Can you tell listeners a little bit about your book and the structure of it?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 34:56

Yes, definitely. Thank you. So "The Famous Lady Lovers," pretty much kind of starts out with the summary really, of kind of the Great Migration moment that starts in Chicago in 1920, with this case around, a woman who left her husband to be with another woman and journalist writing about and had never heard of such a thing before. So very much kind of focusing on Southern migrants coming to cities like New York and Chicago, meeting other women, getting involved in the entertainment industry, which, you know, outside of just these more kind of subaltern spaces, is a really important worksite for Black women who at this time are, you know, still often have no choice except to do domestic work. So the fact that 1000s of women are able to, you know, work and tour and perform, and, you know, sometimes even like, you know, travel internationally is, is really, really significant here. So we have all these women kind of meeting each other in the entertainment industry. And then as I mentioned, there's also a chapter that doesn't focus on entertainers, but more on on the middle class women such as activists, club, club woman and writer, Alice Dunbar Nelson, Lucy Diggs Slowe, who's the first Dean of Women at Howard University, and she has a female partner and they live together off campus and her house is a really important space for Howard, female Howard students to kind of gather and create intellectual community. So yeah, so I just took it so women like Bessie Smith and Lucy Diggs Slowe on the surface, they don't seem like they might have too much in common, but I see them as both, you know, like these, these leaders, these women who are kind of creating culture and, and bringing women together. And so I'm just trying to talk about how Black queer women played this, you know, very important kind of cultural role in this era.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:30

And how can people get a copy?

Dr. Cookie Woolner 36:31

You can get a copy from University of North Carolina press' website, or wherever, wherever you prefer to online. It will be available, I should say, though, right now would just be a pre order. September 12 is the day it will be out and available wherever books are sold. Thank you.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:47

Excellent. Cookie, thank you so much for speaking with me. I loved learning about Gladys Bentley and your book was terrific.

Dr. Cookie Woolner 36:54

Thank you so much. It was wonderful talking to you.

Teddy 37:32

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @Unsung History podcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Cookie Woolner

Cookie Woolner is a cultural historian of race, gender, and sexuality in the modern U.S. She is an Associate Professor in the History department at the University of Memphis. Her book, “The Famous Lady Lovers:” African American Women and Same-Sex Desire Before Stonewall from UNC Press, explores the lives of of Black women who loved women in the Interwar era.

Photo by: Lucy Garrett