Eliza Scidmore

Journalist Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore traveled the world in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, writing books and hundreds of articles about such places as Alaska, Japan, China, India, and helping shape the journal of the National Geographic Society into the photograph-heavy magazine it is today. Scidmore is perhaps best known today for her long-running and eventually successful campaign to bring Japanese cherry trees to Potomac Park in Washington, DC.

Joining me in this episode is writer Diana Parsell, author of Eliza Scidmore: The Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington's Cherry Trees.

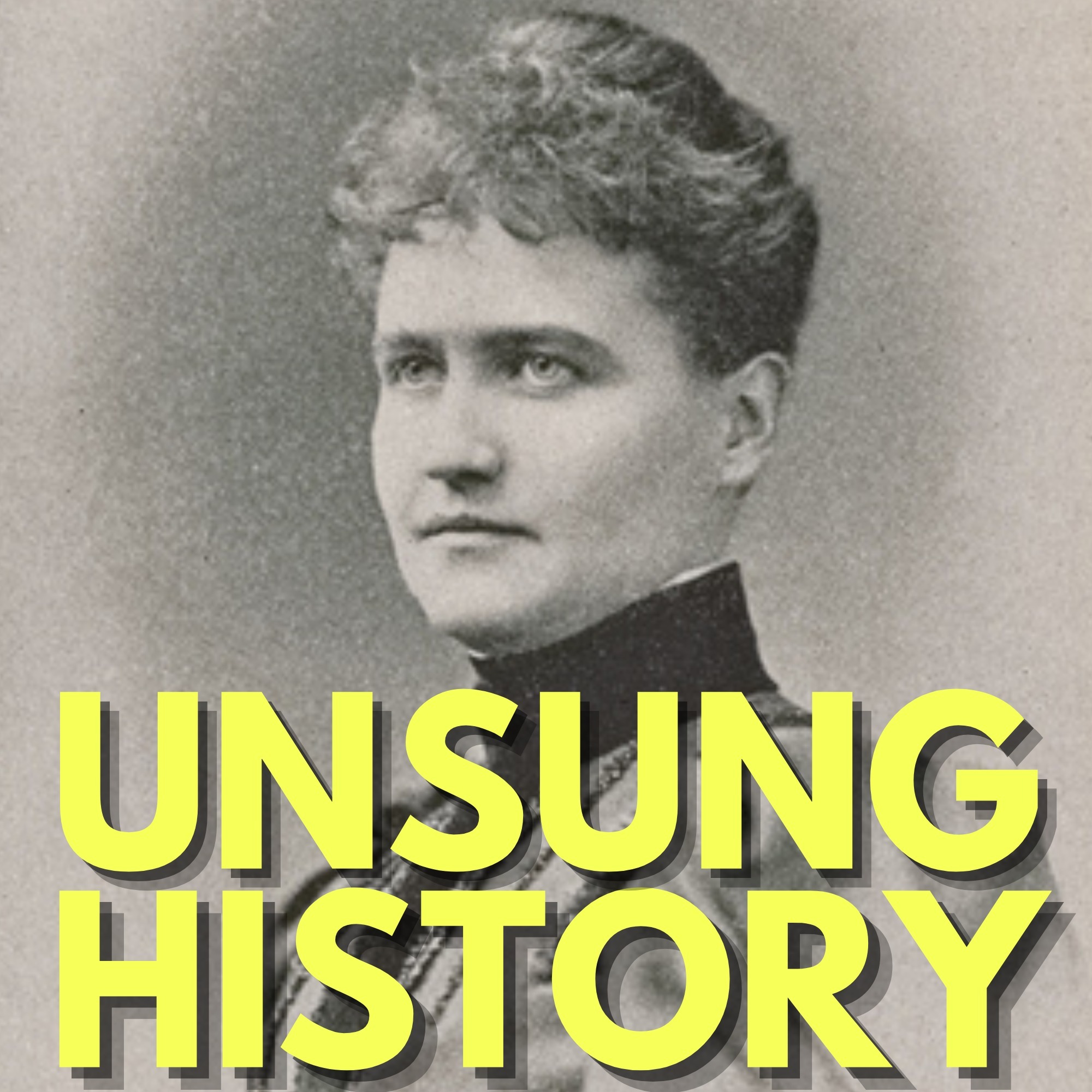

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “My Cherry Blossom,” written by Ted Snyder and performed by Lanin’s Orchestra on May 12, 1921, in New York City; audio is in the public domain and is available via the Discography of American Historical Recordings. The episode image is "Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore [signature]," The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1895 - 1910.

Additional Sources:

- “Cherry blossoms’ champion, Eliza Scidmore, led a life of adventure,” by Michael E. Ruane, The Washington Post, March 13, 2012.

- “Eliza Scidmore,” National Park Service.

- “Beyond the Cherry Trees: The Life and Times of Eliza Scidmore,” by Jennifer Pocock, National Geographic,March 27, 2012.

- “The Surprisingly Calamitous History of DC’s Cherry Blossoms,” by Hayley Garrison Phillips, Washingtonian, March 18, 2018.

- “Cherry Blossoms, Travel Logs, and Colonial Connections: Eliza Scidmore’s Contributions to the Smithsonian,” by Kasey Sease, Smithsonian Institution Archives, August 18, 2020.

- “Celebrating Eliza Scidmore: Nat Geo’s First Female Photographer,” by Kern Carter, Writers are Superstars, May 14, 2023.

- “The American Woman Who Reported On Japan’s Entry Into World War I,”

- By Diana Parsell, Doughboy Foundation, August 8, 2023.

- “The woman who shaped National Geographic,” National Geographic, February 22, 2017.

- “Photo lot 139, Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore photographs relating to Japan and China,” National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Kelly 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore was born on October 14, 1856, in Clinton, Iowa, just over the Mississippi River from Illinois, to George and Eliza Scidmore. Eliza's parents, each on their third marriage, moved the family several times in search of work during a financial panic, eventually returning to Madison, Wisconsin, where the senior Eliza's family lived, on the eve of the Civil War. Sometime after war broke out, George left, moving west, serving in the military, and remarrying briefly. He would never again be actively involved in Eliza's life. Eliza, who went by Lily as a child, was raised by her mother, who, in 1862, moved with Eliza and her older brother George, to Washington, DC, a bustling place in the midst of war, described by a newspaper reporter as, "crammed almost to suffocation." The elder Eliza, passing herself off as a widow, took in boarders, while little Lily attended one of the best girls schools in the country, the Academy of the Visitation in Georgetown. Lily and her brother George, often played in a meadow near the White House, and on October 24, 1864, eight year old Lily asked President Lincoln for his autograph. Sitting her on his lap, Lincoln signed her autograph book, "For Miss Lily Scidmore, A. Lincoln." In 1873, just shy of her 17th birthday, Eliza Scidmore headed off by train to Ohio, where she enrolled in the progressive Oberlin College, the first coed and first integrated college in the United States. After a couple of years at Oberlin, Scidmore intended to transfer to the newly founded Smith College in Massachusetts, but she ended up instead leaving college to begin her career as a journalist. In May, 1876, Scidmore covered the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, writing a handful of letters as a special correspondent with the byline, "Rahumah," for the National Republican in Washington, where her older half brother, Edward Brooks, from her mother's first marriage, was the senior editor. After returning from Philadelphia, Scidmore became the Washington society columnist for the St. Louis Globe Democrat, drawing on her extensive knowledge of and connections in DC, to stand out among the couple dozen women's society reporters in town. Joseph McCullough, editor of The Globe Democrat, encouraged his reporters to seek out stories wherever they could find them, and Scidmore leapt at the chance, traveling west to write about the Dakota Territory in 1877, and to Europe to write about the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878. In between travels, Eliza Scidmore continued to reside and write in DC. A reporter for the St. Paul Daily Globe wrote of Eliza Scidmore in 1884, "Besides being a correspondent, Miss Scidmore is a lady, and is received and treated as such, wherever she goes. She is on intimate social relations at the White House, with the family of every cabinet officer, and has the entree to the most select social circles of the Capitol." However well renowned Scidmore was for her society reporting, travel was her first love. Always in search of her next story, in the summer of 1883, Eliza Scidmore set off on a grand adventure, traveling to the Department of Alaska, which had been a US territory for only 16 years at this time. Traveling on a steamship called the Idaho, Scidmore thrilled as the ship traveled further up Glacier Bay than any ship had previously done. On that trip, Captain James C. Carroll named the glacier and inlet after naturalist John Muir, who had encouraged Americans to go see Alaska. On the same trip, Carroll named a small hilly island near the mouth of the bay, Scidmore Island, after Eliza. This 1883 adventure, the first of many times Scidmore would visit Alaska, led to her first book, "Alaska, Its Southern Coast and the Sitkan Archipelago," published in 1885. The year 1885 also took Eliza Scidmore for the first time, to the country she would come to love, Japan. Her brother George had been working for the US Consular Service in Japan for five years, and mother and daughter traveled across the Pacific to visit him and to travel in the country for six months. When Eliza returned to DC at the end of the trip, her mother stayed behind to live in Japan. Scidmore would travel frequently to Asia, visiting not just Japan, but also China, Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia and India, writing several books and hundreds of articles about the regions she visited. In 1890, Scidmore joined the National Geographic Society, then a new organization. At the end of 1891, she was unanimously elected to be its corresponding secretary, reported in the press as, "the first time a woman has held a position of such honor in a geographic or scientific society of so much importance." Scidmore also wrote for the society's journal, and became an associate editor. Today, Eliza Scidmore is best known for her campaign to plant Japanese cherry blossoms, Sakura in DC. Having become enchanted with the flowering trees during her travels in Japan, Scidmore saw them as the perfect addition to the Potomac River bank, writing that they, "would afford an annual flower show at the season when all Washington is at home, and the city receives its greatest number of visitors and sightseers." Despite her efforts, Scidmore was unable to convince federal officials to adopt her plan, until Nellie Taft became first lady and decided to take up the beautification of Washington as her personal cause. Upon hearing that Nellie Taft planned to create a public gathering place in Potomac Park, Scidmore wrote to her, suggesting she include cherry trees in her planning. Nellie Taft agreed, and with Scidmore's help securing the gift of the trees themselves, the plan finally moved ahead. On March 27, 1912, over two decades after Eliza Scidmore began her quest, she attended the small ceremonial first planting, joining Nellie Taft, and the Japanese ambassador and his wife. What began as that simple planting, is now a four week long annual festival in DC. Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore died at age 72, in Geneva, Switzerland, on November 3, 1928. The next year, a Japanese official carried her ashes to Yokohama, Japan, where they were buried in the family plots, with the remains of Eliza's beloved mother and brother. Joining me now is writer Diana Parsell, author of, "Eliza Scidmore: The Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington's Cherry Trees."

Hi, Diana, thanks so much for joining me today.

Diana Parsell 11:19

Hi, Kelly. Thanks a lot. It's great to be here.

Kelly 11:23

Yes, I was thrilled to learn about Eliza Scidmore. So I want to hear how you first came to hear of her and got interested in writing her story.

Diana Parsell 11:34

Well, I came upon her story, totally by chance. I was working in Indonesia, living in Indonesia for a while. And I bought a book, it was a reprint of an 1897 book called, "Java: The Garden of the East." And I thought it was a very good little book. I was quite absorbed in it, and I was curious about the author. And I thought, "This E.R. Scidmore, what took him out to Java a century ago?" So I went to online and I found a very short Wikipedia entry, and I was stunned to discover that the author was an American woman. And not only that, but that she had a remarkable record of achievement. And the big surprise was that she she introduced the idea of the cherry trees to Washington. I had been a resident of Washington for over 30 years, and I went to see those trees every year. And I had never heard this woman's name. So of course, I was hooked. I needed to know more.

Kelly 12:41

So let's talk about how how you came to know more, like what the process was. You're a first time book writer, I think. So what, you know, how did you trace this? What are the kinds of sources that you had to follow? What are the kind of sources we don't have for her? You know, what, what did that look like?

Diana Parsell 13:04

Well, I started by going to the Library of Congress. Fortunately, I live outside of the Washington area, so it's just a metro ride away. And I started going down to the Library of Congress, and I found copies of her original books, which was a great start. I found her in biographical indexes, quite a few of them, which said she was a pretty important woman in her day. I found a sample of her journalistic work in some newspaper databases, etc. But I really found almost nothing about her personal life. And of course, there was no biography. I enrolled at the time, because I am not trained as a historian. I'm a journalist by background. So I enrolled in a local graduate class in research techniques for narrative writing. And the paper that I wrote in that class was an opportunity for me to find out really, if there were enough sources to you know, even think about doing a book and one of the important things that turned up is that I tracked down a master's thesis that had been done by a distant cousin, back in around 2000. So that gave me a very good introduction to her and some basic clues to the research. And that that became then, it kind of primed the pump of the research for me. I ended up finding family papers in Wisconsin. At the Library of Congress, I started knowing, you know, a little more where to start digging. A huge breakthrough came when I was well into the research, when I discovered that she wrote under a pen name. For almost a decade, she wrote all her newspaper work under a pen name and so it was not showing up. Finally, I found out that her pen name was Ruhamah, which was her middle name, her grandmother's name. Once I plugged that in, I just got this wealth of information. And in the end, I ended up finding about 800 plus newspaper and magazine articles she wrote. Well this was gold, because as you know, newspaper articles, I mean, it was wonderful to get all of this in her own words. But it was also the date lines that told me where and when she was traveling. So that gave me for the first time, the foundation of a timeline so that I could begin to really string her story together. As for the sources I couldn't find, unfortunately, I did learn from a family, I think, from the maybe from the thesis that her own papers had been burned after her death by a family member. So I didn't have that. But the journalism did give me a wonderful entree into her voice. And then I found letters, letters, some that had never ever been ever been mentioned before. And the big trove was a stash of letters at the New York Public Library, to her editor at the Century Magazine in New York. There were additional letters at the National Geographic. Well, this is when you begin to really hear the voice coming through. She was very opinionated. She was very, just a strong minded woman and you can really capture a lot of that in her letters. So those became a really critical source.

Kelly 16:51

The sheer amount of travel she did, is just, it's unfathomable. It isn't like taking a jet plane, right? She was taking boats across the ocean back and forth. Could you talk a little bit about that? And did you do any travel yourself in researching for this?

Diana Parsell 17:09

Yes, she traveled. I was stunned at the amount of travel. I myself had been a journalist. I was stunned at her productivity as a journalist. She did not have online Google reference, you know, tools. She did not have a computer, and that she was just so prolific, that she could turn out 1000 word articles three times a week, and I was able to see some of her original handwriting. And you can see, just from the way her writing races across the page in fountain pen, that she was pretty prolific, and she was pretty knowledgeable. As for the travel, she traveled by train, she traveled by ship she traveled when she went abroad, she traveled by jinrikisha, even in some cases riding around in carts. So it really covered the gamut. And I mean, it did take three weeks to cross the ocean. And there were periods of her life when she was going back and forth to Japan every year or every other year. So it really was astonishing to me to see how much stamina she had apart from her talent. And yes, I did track over some of her travels. The two in particular, I went to Alaska for the first time and also Japan for the first time. As a biographer, a novice biographer, I was very influenced by Robert Caro, the biographer of Lyndon Johnson and other works, who said, you know, place is important, understanding place, and also this emphasis of needing to walk in the footsteps of your subject. So one of the things that I needed to do was to go to Japan during cherry blossom season and to walk under those trees in bloom, which I did. Also I went to Alaska, because she was on the first ship that ever entered Glacier Bay and took tourists north to see Muir Glacier and those other wonders. So I knew that Alaska was important as well. I wanted to do the Inside Passage trip she did, but the timing didn't work out. But I did go to Alaska. And it was important and there is a Scidmore Glacier. It's amazing. We sailed right past it.

Kelly 19:48

One of the things in reading her story is just thinking about how she could be so, really so different than a lot of other people of the time. And so I wonder what sort of insights you have into what made Eliza Scidmore Eliza Scidmore. Like, you know how she became who she became and was this opinionated world traveler working for a living in a time when you know, not that many people at all, but especially women would have been living this kind of life.

Diana Parsell 20:19

She was clearly very intelligent. You can see it in her writings, and in her knowledge. She was very precocious. I love the story of how when she went, she was in her first year of school, and at the end of the year, she won two prizes. And one of those prizes was in a some sort of spelling and reading and writing. The other was geography. And she said, she told an interviewer late in life that her favorite thing as a child was to play with maps and a globe and to make up journeys. She said, "My day dreams were always of other countries." And I saw in this, this is a young person growing up with this tremendous desire, as I call it, to know the world. She had an inquiring mind, and she wanted to know the world. And I think that that propelled her from very, very early on. There was a very telling incident in the book about how she was a bit insouciant in her confidence. She went away to college, to Oberlin, and she left in the middle of her second year. And she had it in, in her mind that she wanted to transfer to Smith College, which was a brand new women's college and the confidence that she had to think that you know that she could compete with really the best female minds in the country, I just thought was a very telling incident. She didn't end up going to Smith. Shortly after that she entered journalism. But she was a quick study, I think in whatever she did, and she did have a lot of independence. It was by her nature, but also by her upbringing. Because as you may have read in the book, she was raised by her mother, a single woman in Washington, DC. So she's growing up, right in the power center of the country, following current events, I think having a good bit of probably independence, because her mother worked. And her mother was encouraging. It's clear that her mother was very encouraging from the get go.

Kelly 22:38

So this time period of Eliza's life, especially her productive time period, is right at the same time that the United States is kind of coming into the world stage, you know, post Civil War. Diplomocy is starting. And you know, I wonder if we could think about that. So Eliza's brother George is working as a consul. That gives her a lot of privilege, really, in how she's able to go back and forth, a place to stay in Japan, helps her nail things, you know, all of that. But I wonder if you could sort of talk about that, like her her growing up as a citizen of the world at the same time that the United States is sort of growing into a citizen of the world?

Diana Parsell 23:22

Yes, I think that it is, I think she is a product of her time. And I found her quite interesting to study because I could see her as a representative figure, during this time of transition. Women were going to college, women were choosing not to marry. I don't know whether she chose it or it was circumstances, but I suspect she, like a number of women in her era, relished that independence and that agency over their lives. And also, yes, I think she she had a nose for news, as I put it. She could sense a lot of these changes that were happening in Asia. So she was out there writing to her editors, "Things are getting very, very tricky in China. Save space in the magazine. I am going to go and spend two months because I think things are gonna blow there and I want to know that country before it happens." So she had a she just had a natural instinct, I think for journalism. And she she was a terrific networker. You could see from the book that she really had a talent for cultivating sources in high places. And so she did have opportunities, but a lot of people have, you know, had opportunities and they didn't make of them what she did. So it was a combination of talent and initiative and seizing opportunities when they came to her.

Kelly 25:02

So one of the really interesting things about her life is she's not just a writer, but she's also a photographer, and she ends up really being instrumental in the direction of National Geographic. You know, I'm sure listeners now, when they think about National Geographic, just think all pictures like that, you know, that's what we've come to think of the magazine as. Could you talk a little bit about that? Her early interest in photography, and how important that was?

Diana Parsell 25:30

Yes, I found the first reference to her taking up photography in an 1890 letter. It was the first letter that she wrote to the editors in New York, at the Century Magazine. She's on her way to Alaska, she it's her third trip to Alaska in 1890, and she writes them a letter and says, "I'm going to, I'm going to Glacier Bay. I know John Muir is going to be there. I would like to profile him. And by the way, I'd love to get photographs, if I can get photographs of him against the Arctic scenery." Well she clearly is carrying a camera at that time. And she is she's she's become friends with Muir and his wife by then. And she writes the letters later and says, "Well, here are copies of my Kodaks. I wish that I had taken more, they came out so well." Well, this is two years after the Kodak box camera, the instamatic box was introduced. So she was clearly an early adopter. And that doesn't surprise us really, when you think of how advanced she was, for a woman her age. So she did travel with a camera. Later, the Smithsonian actually lent her equipment, camera and film. She was visiting places I know in particular, in India, she visited like six museums, and wrote very detailed letters to the head of the National Museum, later the Smithsonian in Washington, where she's telling them about what she saw, what their inventory is, like the ethnological collections, etc. So she's becoming at this, she, you know, she's a colleague of well placed, you know, high level officials in Washington. And she does the same thing. Also, it's it's interesting to know, photographs were not being printed in newspapers and magazines at the time yet, so she would send copies of her photos to her magazine, and they would make woodcuts out of them. So she was taking photographs, starting in the in the 1890s, before photographs even appeared. So she was already used to thinking pictorially when the National Geographic really moved in that direction, and that was after the turn of the century. So she then is writing for geographic and she's taking some photographs. She was definitely an amateur photographer. But one of the important roles that she played at the Geographic was more as a photo editor. She was collecting photographs wherever she went. And that is when they really introduced photographs starting around, I think it was 1905, 1910 in that period. So she was instrumental in pushing them in that direction, because she's helping feed this sudden hunger that they have for good photography.

Kelly 28:42

So you mentioned that she's was quite a networker. She had just amazing friendships just with everybody. It's kind of incredible to think about in you know, you mentioned that she wasn't married. She didn't have kids, but she was always surrounded by people and sort of just this very lively life. And could you talk a little bit about that and and how she was able to the friendships were obviously important and fulfilling, but also was able to use some of those friendships to further the career she wanted and the type of things that she wanted to accomplish, like the cherry trees.

Diana Parsell 29:19

She grew up in Washington, DC, and it is a very important part of her story, because she knew Washington as I put it, like the back of her hand. So when she took up journalism, she already had an edge over some of these other women that were arriving in Washington to report for newspapers around the country. She knew the players in Washington, she knew the politics, she knew the streets. So this was a very important aspect of her early journalistic success, because she she clearly was not a shy person, because her colleagues in Washington I found writings where they're saying, "Oh, you know you can trust what Miss Scidmore writes, because she knows all the all the people she's writing about, she gets invited to, you know, to their homes." She is a, she was an insider essentially. It's probably as much as anything a reflection of her personality that she was not afraid to approach people and, and to, I think she was just a friendly, outgoing person. She was a competent person and she won respect. And I think that I think that had a great deal to do with it. She won the respect and the trust of people. And then those people knew other people. And so it just became really, that she is moving in the circles of the movers and shakers, certainly like at the National Geographic. She joined the Geographic in 1890. She was one of about 12 women among a membership of 400. They elected her the corresponding secretary. Well, that said a lot about her. It was the respect for her writings on Alaska at the time. But John Muir, she became friends with Muir and his wife and she sought them out. So she wasn't afraid. She had enough confidence, which I think is remarkable, because it's an issue we as women have today. And I think that she just had so much confidence that she saw herself as an equal. She didn't feel a need to denigrate herself or to apologize for her writing, which women tended to do in those days, because it was considered unseemly for women to put themselves out there. So she won a lot of respect, because of her expertise and her competence.

Kelly 31:54

A lot of what we've said so far paints Eliza as progressive, you know, she obviously was sort of forward thinking ahead of her time in some ways. But she still had certain biases, and still had certain ways of thinking and writing that a modern reader might look at and kind of cringe at a little bit. Could you talk a little bit about that? And how you navigate that as a biographer, making sure that you can talk about those pieces without taking away from everything she was?

Diana Parsell 32:24

Yes, it was a delicate question. And it was one that concerned me a great deal, because as I've mentioned, I'm not a historian. I think talking about some of these issues, like you know, colonialism and cultural appropriation, and again, white supremacy and on and on, I think there's a vocabulary that you need, in order to address some of these issues in the context of the day. I knew that I didn't have that. I also knew that I was not writing a critical analysis or, you know, a book that was theoretically based, an analysis, like you typically get from academic presses. My press was Oxford, but they encouraged me to do what I wanted to do, and that is to write a book that would be accessible to a wide readership. But I knew I had to address that, at least in passing, for that book to be taken seriously. And so I discussed it with my editor, and she understood, and she actually sent the manuscript out for review for several experts in the field, and asked them to provide feedback. And with their help, I was able to insert a little bit of that context, to at least address that issue, knowing that I was not going to get into a long discussion of that.

Kelly 33:52

One of the sort of really striking passages in the book is when she goes to what is then the top of the Washington Monument, not as high up as it is now, could you talk a little bit about it? It's still frightening to go to the top of the Washington Monument, if it's me, so talk a little bit about exactly what she did and why she did sort of what that what that tells us about her.

Diana Parsell 34:14

So the incident you're referring to occurred in 1883. And it was one of those eureka moments that you have as a researcher, because I've mentioned that I went in and I was reading her journalistic work. And I have all of these columns. She's writing three columns a week for a newspaper in St. Louis. She has just come back in the fall of 1883, from her first trip to Alaska. That fall, she is scrambling, of course to find material to write about in her column. So I find in this column, and I was just stunned how she's describing for readers in St. Louis, how they have started this project along the Potomac. The Potomac really came up almost to the base of the Washington Monument at the time. It was very low lying marshy ground, it tended to flood. It, it, the tide would come in and out, and it would get it would make that ground very marshy. And so for years, there were complaints about it. And finally in the 1880s, the Army Corps of Engineers decided, they got the money from Congress to fill in that ground. Well, that ground west and south of the Washington Monument, became what we know today as Potomac Park. So she goes down to the Washington Monument in order to report on this, and she rides to the top of the monument. It is still under construction. She has to ride a platform elevator, it has a iron cage around it, and it even has these very clever pulleys that would reach out and it would carry the stones to the top and then the pulleys would swing out and drop those stones into place. Well the only way to get to the top of the monument was on that elevator. And so she described that ride. But the really wonderful thing was when she reached the top, and she is telling readers, as she's describing what she sees below, and she says, "This is going to one day be the largest and most beautiful park in Washington, a place of magnificence in future administrations." She had not even gone to Japan at this point. But already I could see, wow, here is the seed of what eventually became her idea to bring cherry trees to Washington, and to plant them in Potomac Park. And a really important aspect of this is that it forced me to change the structure of the book, because I had assumed that the cherry trees, you know, they were planted in 1912, that this would come maybe in the last third of the book. Suddenly, when I found this column, and I realized that she followed the development of Potomac Park as a young reporter, then you begin to see the evolution of that idea. So then I realized I really had two parallel stories going. One is her life story. But the other was the evolution not just of the cherry trees, but of Potomac Park, because that is where it began. So I went back and restructured the book, because I could see that that really was the beginning of this original idea that she had.

Kelly 38:00

And what an idea it was! She really, really would not let go of this idea. Could you just talk a little bit about that, that this amazing, anyone who has been to DC in cherry blossom season knows just how incredible this is. And it really took a lot of dedication to get there.

Diana Parsell 38:21

Because we are we've already talked about how her brother was a consul officer in Japan. And so she went back and forth to Japan many times. She became an expert on Japan, she loved Japanese culture, she admired the Japanese greatly, especially in contrast to China. She loved how the Japanese were modernizing their country without really losing a sense of their traditions. And one of those traditions was cherry blossom season. So she loved the cherry trees. And she said, "These, you know, these cherry trees are the most beautiful thing in the world when they're in bloom. Why have we not imported these to America? Why are we not having them in our parks? We should do it and what better place that in the nation's capital," which was then beginning to become a destination, a tourism destination for Americans. So she came back and proposed this to the men who were in charge of the city parks. And of course, they're building Potomac Park at this time, and they just hadn't, you know, they just listen, they heard her out. And then they ignored her. And this happened, you know, two or three times. And then finally, the Tafts came to the White House in 1909. And that's where we have this opportunity that presents itself and she seizes it and that is that Mrs. Taft herself, decides that she would like to create a gathering spot in Potomac Park to create a build a bandstand and to have concerts there. Eliza Scidmore gets wind of this idea and sends Mrs. Taft a note trying to get her backing to have some cherry trees planted along the Potomac and Mrs. Taft, who also appreciated Japanese culture had even lived in Japan for a short time, seized on this and took this up. And that from that point on the two of them were essentially partners in this. And I do want to add, because this was another surprise finding in the book that Eliza didn't just introduce the idea of the trees, she became the chief mediator between Mrs. Taft and a gift from Japan, when they offered to donate 2000 trees. So that kicked Mrs. Taft's project up many, many notches in scale. And we owe that to Eliza Scidmore because of her Japanese contacts.

Kelly 41:01

Yes, in another time, she clearly would have been an amazing ambassador herself.

Diana Parsell 41:07

She would have undoubtedly, yeah. She was kind of an informal people ambassador, really. Yes.

Kelly 41:16

Well, this is an incredible story. Her life is just fantastic. And it's such a great read. Can you tell listeners how they can get a copy of the book?

Diana Parsell 41:24

Yes, the book is available in major bookstores like Barnes and Noble. You can get it on bookshop to support your independent bookstores. If you go to my website, I have a book page that will give you a list of sources. And my website is www.DianaParsell.com.

Kelly 41:48

Excellent. Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Diana Parsell 41:51

No, I just want to thank you a lot. I find it remarkable that we have this as you've mentioned this amazing celebration and this amazing place in Washington and that for over 100 years, we have known almost nothing about the woman to whom we owe this. So I love the idea of having a chance to give her the due, and to write her into the history books which I think she deserves. Thank you.

Kelly 42:21

Absolutely. Thank you.

Teddy 42:22

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on twitter or instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Diana Parsell

Diana Parsell is a former journalist and science writer in Falls Church, Va. She spent years as a reporter looking for good stories, and stumbled onto a great one while living and working in Southeast Asia. An 1897 travelogue on Java inspired her to write the first-ever biography of its author in Eliza Scidmore: The Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington’s Cherry Trees.

A native of southeastern Ohio, Diana has made Washington her adopted home since graduating from college. She began her editorial career at National Geographic, and had done writing and editing for many other publications and organizations, including the National Institutes of Health, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and The Washington Post. Her work has appeared in a wide range of print and online outlets.

Diana was an English major at Marietta College, studied publication design and management at George Washington University, and has master’s degrees from the University of Missouri School of Journalism and Johns Hopkins University. Long active in the local literary community, she was among the founding writers and editors of the online Washington Independent Review of Books.

For her new book Diana received a Mayborn Fellowship in Biography and the 2017 Hazel Rowley Prize from Biographers International Organization (BIO). Other honors include fellowships from Rotary International and the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing, and a residency at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts.

Her volunteer activities including serving as a doce… Read More