Eleanor Roosevelt's Visit to the Pacific Theatre during World War II

In August 1943, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt set off in secrecy from San Francisco on a military transport plane, flying across the Pacific Ocean. It wasn’t until she showed up in New Zealand 10 days later that the public learned about her trip, a mission to the frontlines of the Pacific Theater in World War II to serve as "the President's eyes, ears and legs." Eleanor returned to New York five weeks and nearly 26,000 miles later, having seen an estimated 400,000 troops on her trip and producing a detailed report on American Red Cross activities in the Southwest Pacific for Norman Davis, Chairman of the American Red Cross.

Joining me in this episode is journalist Shannon McKenna Schmidt, author of The First Lady of World War II: Eleanor Roosevelt's Daring Journey to the Frontlines and Back.

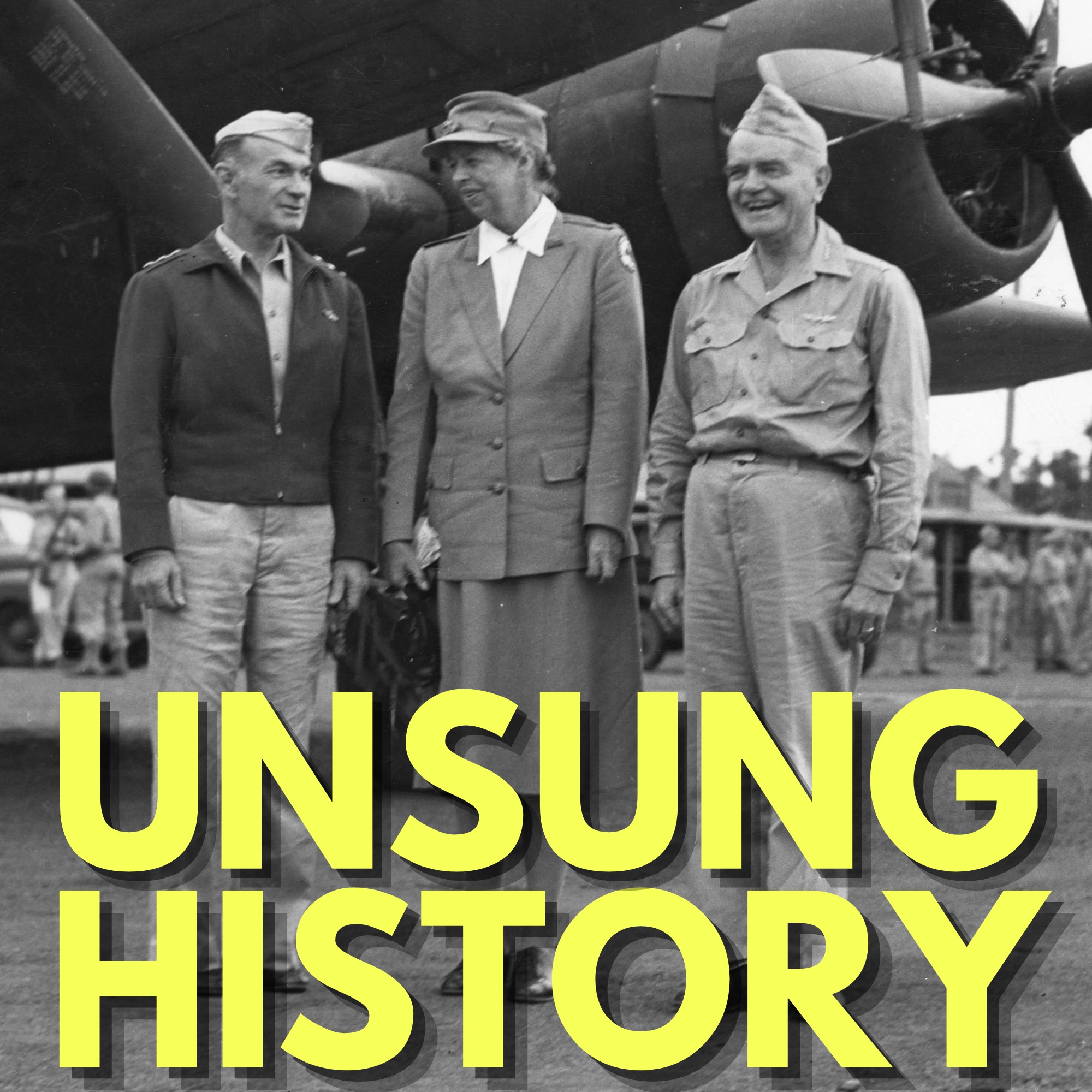

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode audio is from the December 7, 1941, episode of Over Our Coffee Cups, a weekly 15-minute radio show hosted by Eleanor Roosevelt on the NBC Blue network; in 1942, these recordings were donated to the Library of Congress as a gift from the sponsor, the Pan-American Coffee Bureau; the audio clip can be accessed on the C-SPAN website. The episode image is “Eleanor Roosevelt, General Harmon, and Admiral Halsey in New Caledonia,” taken on September 16, 1943; the image is in the public domain and is available via the National Archives, NAID: 195974.

Additional Sources:

- “This Is What Eleanor Roosevelt Said to America’s Women on the Day of Pearl Harbor,” by Lily Rothman, Time Magazine, Originally published December 7, 2016, and updated on December 6, 2018.

- “ER and the Office of Civilian Defense,” Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project.

- “In the South Pacific War Zone (1943),” Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project.

- “Eleanor Roosevelt: American Ambassador to the South Pacific,” by Glenn Barnett, Warfare History Network, July 2006.

- “A First Lady on the Front Lines,” by Paul M Sparrow, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, August 26, 2016.

- “Eleanor Roosevelt and World War II,” National Park Service.

- “Eleanor Roosevelt: South Pacific Visit [video],” clip from The Roosevelts by Ken Burns, September 13, 2014.

Kelly 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers, to listen too.

Just before 8am local time, on Sunday, December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service launched a surprise military strike on Pearl Harbor, the headquarters of the United States Pacific Fleet on the island of Oahu, destroying 21 American ships and 250 aircraft, and tragically killing over 2400 Americans. The next day, December 8, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave his now famous speech to a joint session of Congress, calling the previous day "a date which will live in infamy," and asking Congress to declare war on Japan, which it did with near unanimity. FDR, though, wasn't the first public figure to address the American people in the wake of the attack. Instead, it was the First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who on her regularly scheduled weekly radio program, "Over Our Coffee Cups," on December 7, spoke to the American people about the horrific events of the day, particularly addressing the women and young people of the country. Even before the formal declaration of war, Eleanor had been involved in the war effort. In September, 1941, Eleanor was appointed assistant director of the Office of Civilian Defense, which was headed by Fiorello LaGuardia. Perhaps unsurprisingly, having the First Lady serve in an official government position was controversial, and she resigned six months later, saying, "I do not want a program which I consider vitally important to the conduct of the war, and to the well being of the people during a period of crisis, to suffer, because what I hope is a small but very vocal group of unenlightened men are now able to renew under the guise of patriotism and economy, the age old fight for the privileged few against the good of the many." Still anxious to help, and never one to sit on the sidelines, Eleanor looked for other ways to contribute to the war effort. Throughout her time as First Lady, Eleanor had served as the President's eyes, ears and legs, and she continued that role during World War II, at first traveling domestically to the west coast to organize Offices of Civilian Defense there. In October, 1942, FDR asked her to go a little further afield, visiting England in his stead. The trip was part diplomatic mission, strengthening ties to one of the US's closest allies, part fact finding as she observed the role of British women in the war effort, and part morale boosting as she visited American troops stationed overseas. So as not to make a target of Eleanor, she was referred to in communications about the trip by her codename, "Rover," an apt description of the woman of whom one reporter wrote, "She walked 50 miles through factories, clubs and hospitals. She walked me off my feet." In August, 1943, Eleanor traveled abroad again, also at FDR's behest, this time to the war's frontlines in the South Pacific. She set off in secrecy from San Francisco on a military transport plane on August 17, flying across the Pacific Ocean to Honolulu, followed by Christmas Island, Penrhyn Island, Bora Bora, Aitutaki, Tutuila, Viti Levu and New Caledonia. Before the trip, she wrote in one of her daily "My Day" columns, "I'm about to start on a long trip, which I hope will bring to many women a feeling that they have visited the places where I go, and that they know more about the lives their boys are leading." For the sake of security, publication of the column was delayed until August 28. Before departing, Eleanor had arranged with Norman Davis, the chairman of the American Red Cross, to use the trip as an opportunity for her to inspect Red Cross services and clubs across the region. At Davis's suggestion, Eleanor, who was a longtime volunteer with the Red Cross, dating back to World War I, wore a Red Cross uniform for the duration of the trip. It wasn't until Eleanor arrived in New Zealand on August 27, 10 days into the trip, that the public learned that she was in the South Pacific at all. Eleanor spent a couple of weeks in New Zealand and Australia, where General Douglas MacArthur's staff aid, Captain Robert White reported, "Wherever Mrs. Roosevelt went, she wanted to see the things a mother could see. She looked at kitchens and how the food was prepared. When she chatted with the men she said the things mothers say. She went through hospital wards by the hundreds. In each she made a point of stopping by each bed shaking hands and saying some nice mother-like things." Upon returning to New Caledonia, Eleanor learned from Admiral William F. Halsey, that he was granting her request to visit Guadalcanal, with stops at a couple of other islands along the way. Halsey had originally opposed the request to take the First Lady, or any, what he called "do gooders" that he would have to play the solicitous host for, into an active fighting zone. But several weeks into her trip, Halsey was won over not just by Eleanor's actions, but by the reactions of the troops to her visit, saying, "I marveled at her hardihood, both physical and mental. She walked for miles, and she saw patients who were grievously and gruesomely wounded. But I marveled most at their expressions, as she leaned over them. It was a sight I will never forget." After Guadalcanal, Eleanor headed back via Espiritu Santo, Wallace Island, Christmas Island, and Honolulu, finally arriving back in New York on September 24, 30 pounds lighter, having logged nearly 26,000 miles, and having seen an estimated 400,000 troops. Eleanor wrote that the trip left her with, "a sense of pride in the young people of this generation, which I can never express, and a sense of obligation, which I feel I can never discharge." Joining me now, to help us learn more about this incredible trip, is journalist Shannon McKenna Schmidt, author of "The First Lady of World War II: Eleanor Roosevelt's Daring Journey to the Frontlines and Back."

Speaker 1 9:58

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. I'm speaking to you tonight at a very serious moment in our history. The cabinet is convening and the leaders in Congress are meeting with the President. The State Department and Army and Navy officials have been with the president all afternoon. In fact, the Japanese ambassador was talking to the president, at the very time that Japan's airships were bombing our citizens in Hawaii and the Philippines, and sinking one of our transports loaded with lumber on its way to Hawaii. By tomorrow morning, the members of Congress will have a full report and be ready for action. In the meantime, we the people are already prepared for action. For months now, the knowledge that something of this kind might happen, has been hanging over our heads. And yet it seemed impossible to believe, impossible to drop the everyday things of life, and feel that there was only one thing which was important: preparation to meet an enemy no matter where he struck. That it is all over now, and there is no more uncertainty. We know what we have to face. And we know that we are ready to face it. I should like to say just a word to the women in the country tonight. I have a boy at sea on a destroyer. For all I know he may be on his way to the Pacific. Two of my children are in ko cities on the Pacific. Many of you all over this country have boys in the service who will now be called upon to go into action. You have friends and families in what has suddenly become a danger zone. You cannot escape anxiety, you cannot escape a clutch of fear at your heart. And yet, I hope that the certainty of what we have to meet will make you rise above these fears. We must go about our daily business more determined than ever to do the ordinary things as well as we can. And when we find a way to do anything more in our communities, to help others, to build morale, to give a feeling of security, we must do it. Whatever is asked of us, I'm sure we can accomplish it. We are the free and unconquerable people of the United States of America. To the young people of the nation, I must speak a word tonight. You are going to have a great opportunity. There will be high moments in which your strength and your ability will be tested. I have faith in you. I feel as though I was standing upon a rock. That rock is my faith in my fellow citizens. Now we will go back to the program which we had arranged for tonight.

Kelly 12:56

Hi Shannon, thanks so much for joining me today.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 12:59

Thanks so much for having me on your show.

Kelly 13:01

Yes, I am so so excited to talk about Eleanor Roosevelt and this incredible trip. So tell me a little bit about how you got interested in this story. I know you are no stranger to travel yourself. So you know what, what led you into writing this book?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 13:19

Yeah, well, I love that question, because what really led me to write "The First Lady of World War II" was really, it grew in large part out of my love of travel. I really connected with Eleanor Roosevelt, the adventurer and the traveler, and how I came across the specific idea for the book, I was reading a collection of her column "My Day." It's a column that she wrote for 26 years, six days a week. And there was a brief mentioned that she visited Australia during a tour of the Pacific Theater. And it was a fleeting mention, but it immediately caught my interest because I had recently been to Australia and New Zealand. And the first thought that struck me was amazement at the distance that she would have traveled to get there, and under wartime conditions. She went in a in a bare bones transport plane. And so the book really spiraled from there. But that that was the initial hook that that inspired me to write it.

Kelly 14:11

Her energy is just unimaginable, this idea of like writing this column six days a week for decades, doing this amazing travel. So when you're looking at something like this, there's so much out there about Eleanor Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, but relatively little about this trip itself. How do you go about doing that research, figuring out what sources to look at, where to find the pieces, because what you end up doing then in the book is really kind of a day by day description of the journey and following her path. So how do you piece that all together?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 14:45

I really followed a lot of threads to put this together but at the heart of the book are Eleanor's own observations and words and writings. My, the bulk of my research was done at the FDR Library in Hyde Park, New York, and there's a wonderful, wonderful resource called the Pacific Trip File. And it's like a time capsule of this trip. And there were a lot of materials in there. Everything from the list of the bomber crew that flew Eleanor into Guadalcanal to formal dinner seating charts, to that to the miles that she logged, a mileage log. So that that was a very, and it's a wonderful thing just to just to comb through and to look through that it really I felt like such a connection with her and the trip while I was looking through this specific trip file. There, also, she gave a lot of speeches, when she got back, she wrote a lot of articles, "My Day," of course. And she also kept a diary that she shared in installments with the President. In fact, Eleanor, she only wore Red Cross uniforms on the trip. And part of the reason that she did that was to pare down her clothing so that she could adhere to a strict luggage limit. Because what she did was she called a heavy manual typewriter with her to the Pacific so that she could write this diary to share with the President and so that she could keep writing "My Day" in real time, and copy was wired to her editor in New York.

Kelly 16:06

What were her goals in going on this trip? I mean, this is a this is not something that first ladies or even presidents have typically done in wartime to go on this extended trip right on the front lines. So what was the goal of this? What was she hoping to accomplish? You know, and then what did she actually like? Did she meet those goals in, you know, what you found?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 16:30

Yeah, so she had a few reasons for going. A primary reason for the trip was to thank US troops for their service. She felt an enormous sense of obligation toward the generation of young men being sent into battle and who, frankly, were bearing the brunt of the war. And that weighed very, very heavily on her. So she made a point to address troops. And in all, she addressed about 400,000 troops throughout her time in the Pacific. It was also an informal diplomatic mission to allied nations, Australia and New Zealand and to see the war work that women were doing in those countries, which was at the time more extensive than what women in the United States were doing. Although women in the US were doing a lot, of course. And also, she went as a representative of the American Red Cross, which is why she was wearing the uniforms. And she went to the head of the Red Cross when the trip was decided, and she said, hey, I can inspect your facilities in the region. And the head of the Red Cross was was into that idea, because he had been planning to send someone anyway. And also, another important reason for the trip was that by the summer of 1943, Eleanor set out in August of 1943, she felt that people were, that the people on the homefront were overly optimistic about the war's outcome, and that they were becoming dangerously complacent. There were strikes at war production factories across the country. People were complaining about food rationing and shortages. And so she felt that the trip would link the home front and the fighting front, really reminding the nation that they couldn't give up on their duties until the war was won. And then any slackening in production risked the lives of the men on these distant battlefields. So she had she had Eleanor being Eleanor, she added a lot onto a plate and she had to she had those many reasons for going. And I do think it was successful. I think it was successful, in part because only Eleanor could do this trip and do it successfully. And she had all the skills, the diplomatic skills, the people skills, the reporting skills. But what she also had was this platform that she had built up over a decade as First Lady to communicate her findings to the American public. So she didn't go in a vacuum. She She reported to them exactly what she found, what their servicemen were facing, what she expected of the home front. So she really she, she not only could go to the Pacific Theater do this trip, she was reporting to the President and the home front while she was there.

Kelly 18:54

Can we talk a little bit about the challenge of reporting. So there were also reporters in the region on the frontlines with the troops, that there's this tension between wanting to share what's happening, but also wanting to hide important military secrets. And so there's this ongoing tension with sensors. Can you talk a little bit about how that affected what Eleanor was allowed to write, the way she was allowed to talk about the trip?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 19:22

Yeah, so just like any other correspondent in the Pacific Theater, Eleanor had to adhere to wartime censorship rules, and they were they were voluntary in the United States. They were highly journalists largely adhered to them. They were highly restrictive in the Pacific Theater. So she couldn't mention things like the number of troops stationed at bases. She couldn't mention by name all of the islands that she visited. I was actually surprised though, at how much she was allowed to relay in her columns and in her speeches, and articles.

Kelly 19:52

So one of the things of course, you mentioned she's doing is troop morale. So let's talk a little bit about what what that was like, what she's able to do when she gets to these places and the way that her personality and the person that she is, allows her to really help with that.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 20:11

I think that one of the things that the troops saw reflected back at them when they looked at Eleanor was that this was no superficial PR junket or a political gesture. She was there because she was genuine. She's wearing a uniform just like they are. She's traveling in a military transport plane, she traveled in the same military transport plane the same, the entire trip. She's sharing space with supplies and sacks of mail. And so I think that that very much resonated with the troops. And morale was hugely important in the Pacific Theater and one of Eleanor's goals was to get to the island of Guadalcanal. And standing in Eleanor's way was Admiral William Halsey who was the commander of the South Pacific forces and he thought, "Oh, here's yet another VIP on a superficial PR junket." And when they first encountered each other at his headquarters, he brusquely shut down a suggestion of her going to Guadalcanal which was still on the front lines. He said he would wait to make a concession until after she travelled to Australia, New Zealand, came back to his headquarters, and he would see what the status was of the battle he was overseeing, and if he had the available fighter planes to escort her into Guadalcanal. Well, by the time Eleanor returned to his headquarters a couple of weeks later, he had completely changed his tune about her being in the Pacific. And I believe that ultimately, he allowed her to go to Guadalcanal. I mean, he saw, he saw that her motivation was genuine, through his own observations, reports from other military personnel in the region and a tremendous amount of press coverage. Ultimately, why I think he allowed her to go to Guadalcanal was that morale, wins wars, and he could see the uplifting effects that her presence had on the troops. I love it that here's this rough, tough admiral. And he said, what he marveled at most were the expressions on the men's faces as Eleanor leaned over them in their hospital beds. And to me, that just speaks volumes about the the importance of morale and how he saw her affecting morale while she was in the Pacific.

Kelly 21:34

And it wasn't just men who were Roosevelt supporters, right? Like there were people who met her and actually changed their mind about her upon meeting her.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 22:29

I do I love that. She she left many servicemen in her wake like a fan, you know, because the servicemen didn't leave their politics at home when they went overseas, of course. And I love there's there's one servicemen who wrote in a letter home, he said, "I'd always been against her until now," but that she had just the way of seeming like she came all the way to the Pacific just to talk to you, and you and you to each one of them as individuals.

Kelly 22:57

And could you talk a little bit about it wasn't just, you know, individuals that she met that might not have been Roosevelt fans, but there were people who were real critics of what she was doing not just on this trip, but in all the trips and things she was doing, but especially in this trip. I think you talked about one particular columnist who is clearly just an anti-Eleanor person. Could you talk a little bit about that and what their objections were to her going on this trip to doing this kind of work?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 23:25

So pretty much everything that Eleanor did from day one as First Lady generated controversy, and this trip was no different. So the trip was kept secret for the first 10 days as she made her way through the South Pacific for security reasons. But once she reached New Zealand news broke, and there wasn't so much surprise that she turned up on the other side of the world, but that it had been such a well kept secret. And of course, the media floodgates opened. There were people who supported what she did. There were detractors. And yes, this, this trip added fuel to the fire for her critics. There was one columnist in particular, Westbrook Pegler, and he was anti-Roosevelt administration, and he very much wielded his poison pen against Eleanor in particular. And, you know, he, of course, went on a screed about wasting fuel and, you know, completely disregarding the fact that she traveled on a regular military transport flight. But one thing that I love is that Eleanor's first inspection stop was a little tiny island called Christmas Island. And the GIs on Christmas Island after news broke and they were able to write about Eleanor's visit to their island in their troop publication, they took on her detractors. And they they poked fun at Westbrook Pegler in particular, I think they called him Pegbrook Wessler and that he slung his arrows at Eleanor but that they wanted him and everybody else to know that she brought that island of forgotten men very much back to life. And I just, I just love that quote and another GI journalist reported in their troop publication that, "It takes great courage to do what Mrs. Roosevelt is now doing. And you have to hand it to her. She has what it takes." So to the people that, they were some of the people that it really mattered to about her trip. And they, they expressed that.

Kelly 25:24

So let's talk about these forgotten men. So what is the Pacific theater like? This is very different than the war in Europe, which a lot of us have read a lot more about, and which I think the American people at the time probably knew a lot more about what was happening. So can you talk about what what life was like for men who were fighting in the Pacific Theater?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 25:47

Life was very harsh for the men experiencing jungle warfare in the Pacific Theater. And Eleanor went to great lengths to understand jungle warfare, even trekking through the jungle on on a simulated training exercise. She talks about how they warned her that there would be shooting and yet it seemed like she stepped on a soldier before she almost stepped on him before she even saw him. And it seemed like a gun went off under her feet. So she was very much interested in finding out this new kind of warfare for American servicemen. And she was very forthright in reporting back to the American public about what this was like, the human cost. And in one of her radio addresses, after she got back, she told people to stop complaining about food rationing and shortages, because it was nothing compared to lying on your back in a jungle swamp, while an enemy camouflaged in the trees took shots at you. And in another speech, she talked about the shattered eyes of the men who had endured the savagery of jungle warfare. So she's very much going to great lengths to find out about that. And then she also was boosting morale for the men through the South Pacific, like the ones on Christmas Island, and other islands that linked the supply and communications route between the United States and Australia. And these men felt marginalized and distant from the war. And as if they weren't making enough of a contribution. And FDR asked Eleanor to particularly visit these islands and assure the men there that he knew the valuable job that they were doing. So it's neat to see that she kind of had this encompassing mission that thought about the various stations and positions for the men in the Pacific.

Kelly 27:33

It's not just the warfare, that's difficult there. Right? It's like, they just don't have anything to do in some places. The the islands are each unique and different. But in some places, it's like they don't even have anything to do in their free time. Could you talk a little bit about that and the the sorts of things that Eleanor saw when she was there?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 27:52

So when Eleanor when this trip was decided, and she went to the head of the Red Cross, as I mentioned, she offered to inspect their facilities in the region. And she ended up giving that the head of the American Red Cross a nine page report after she got back. And part of what was in the report was exactly what you were referring to, that the men on these islands needed recreation. They needed supplies, they needed pens and paper to write letters home. It was very much a recreation and a morale building. And she was more forthright in her report than she she was, of course in her her public columns, and on how that they could improve things like that.

Kelly 28:39

So you mentioned that she really wanted to get to Guadalcanal. Can we talk a little bit about why was that so important to her to get there? You know, what, what is it that she wanted to accomplish by going there?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 28:51

Getting to Guadalcanal was Eleanor's ultimate goal of the trip. And it was still on the front lines. And visiting there was really a tribute that she felt she owed to the men in uniform to see where so many of them had lost their lives or received their injuries. And Eleanor, she had gone to Great Britain the year before in 1942. And that was also a difficult trip, she pushed herself, but this time in the Pacific, I think that she felt even more driven. She really wanted a wartime task that would require her to put forth endurance and courage just like the men were. And so it was very important for her to get there and she also felt that she would be perceived as lacking courage if she didn't go. And she told FDR that she would never be able to face the men in the hospital again if she didn't go because she thought that they would think she was lacking courage. And FDR first stood in Eleanor's way. He was totally for her going to the Pacific they decided together that she would go. He was understandably reluctant to have her put in harm's way. Well, she wore him down. And when she set out for the South Pacific, she had letters from him addressed to the commanders on the ground in her bag. And so he was eventually, she eventually won him over, FDR, and about saying it's okay for you to go. And then the other person, like I said, that she had to convince was Admiral Halsey. And he did allow her to go to Guadalcanal.

Kelly 30:29

So one of the things you talked about in the book is race relations in in the armed forces and race relations between the members of the American military and the peoples of the islands, so especially on New Zealand, for instance. Could you talk a little bit about that? And Eleanor Roosevelt is a fair bit more progressive than FDR, even, in things like race relations. And so, you know, what is she trying to do while she's there? What is she able to accomplish? And then, of course, she gets herself into a little bit of scandal while she's there because of this.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 31:07

So when Eleanor went to Great Britain, the year before, the Secretary of War, Secretary of War Stimson asked FDR to ask Eleanor, to please don't mention race. They didn't really want to let on that Black American servicemen were treated better in Great Britain than they were then in the United States. So she acquiesced to that request for that trip. Fast forward a year. She's in the Pacific, and we're now a year closer to peace. It's it's pretty certain at this point that the allies are probably going to be victorious. How long is it going to take we don't know at this point. So she has a two pronged mission. She's rallying people to see the war through to its conclusion, and she's looking ahead and preparing for peace. And part of that was making a world that was equitable for everybody. And before she left Australia, she gave a major speech, and she addressed race in that speech. So she acquiesced to the request in the in Great Britain, but here she is in the Pacific, and she's out front with it. And her trip got racists riled up in the United States, because in New Zealand, which, which was an integrated society with with the Maori, the Indigenous people of New Zealand, but when she went to Rotorua, the home of the Maori, she was greeted by a very famous Maori guide and cultural ambassador. And she gave Eleanor a traditional Maori greeting, which was a pressing of the noses. And a single photographer caught one photograph of this. And so there's only one photograph in existence of this moment. And that got racists riled up in the United States, and a congressman even ranted about it on the floor of the House of Representatives. So they were very much at work during her trip to the Pacific.

Kelly 33:07

And you have that photograph in your book.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 33:10

Yes. I was very pleased that my publisher and of course, because there's only the single image, it's, you know, under copyright. And so I was very pleased that my publisher went to the lengths they needed to go to include that in a photo insert in the book.

Kelly 33:25

Yeah, it's incredible. I love love that photograph. And so the Roosevelts, of course, are not just sacrificing in these ways. But all four of their sons were also in World War II. Could you talk a little bit about that, and the way that that helps Eleanor understand the sacrifices that people were making?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 33:43

I think it absolutely helped her understand the sacrifices. And also, part of what she wanted to do in the Pacific was to let the women in the United States know what was happening to their men, and what life was like for them, the mothers, the wives, the you know, sisters. And as a mother, she very much felt that, and she talks about how even she and FDR didn't know where their sons were. You know, they didn't have any special information. And her son James, who was a Marine fought in the Solomon Islands campaign that included the Battle of Guadalcanal. He did not fight on Guadalcanal. It was another island, but he was involved in the Solomon Islands campaign. And he especially helped her when she went to the Pacific understand jungle warfare. If he told her well, you know, you can hack away at the jungle all night and go half a mile. And she said she didn't you she, she understood what he was saying, but she really understood it when she went there and saw things for herself. In fact, Time Magazine had this wonderful quote, and they said that, that she was probably the American mother who had been closest to the war, and who had seen as so much of the panorama of the war, and been close to the sweat and boredom, the suffering. So being a mother of four sons on active duty in the military was was very, I think instrumental to her in her war efforts.

Kelly 35:12

You touched just briefly in the book, but I wonder if you could talk about it here the relationship between Eleanor and FDR. They're clearly you've mentioned several times, they made these decisions together about where she's going. She's sending reports back to him. She's helping with policy. But that's not the same as a romantic relationship. So could you talk a little bit about that, and what what it is that they're doing, how their partnership is working at this point in the war.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 35:41

That's one of the things that I realized while I was writing this, and you know, there it's it's very well known that Eleanor and FDR had their troubles in their marriage. He had an affair with Lucy Mercer, which which kind of severed the romantic part of their relationship. But what I found in the they cabled each other every few days, while Eleanor was in the Pacific, they exchanged notes, very affectionate and loving notes, checking on each other's health, news about family members and making plans to see each other as soon as she returned from the Pacific. And so from these correspondence, I really felt that it showed it showed the love that was still there and affection in their relationship despite a couple of decades of, of baggage. And the other thing is that Eleanor's travels were a touchstone for her and FDR to keep in touch with each other a link. After each one of Eleanor's trips, they would get together and they would talk about her findings. And when she came back from Great Britain, she was gone like a month and FDR is like, "Would you just send her home please?" And when the when the plane flew into Washington, DC, she could see this hoopla down on the tarmac and she knew it was FDR and the Secret Service, and that he had taken time out of his busy wartime schedule to come meet her after she returned. And same after the Pacific. They they met and discussed her findings. And he was always supportive of her travels. Travel was a reason that Eleanor was considered an unconventional First Lady. And FDR was always supportive of of her travels for his own personal political gain with the information she gathered. But I think that he also knew that it was something she needed personally.

Kelly 37:32

You mentioned that during the trip, she was already thinking ahead to peace. And then after, of course, after she gets back, she's instrumental in thinking about what happens next for service members, what happens next for world peace. Could you talk just a little bit about the kinds of things she's able to accomplish after she returns?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 37:51

A near term goal for Eleanor was to see a support program established for returning servicemen. She talked with servicemen extensively in the Pacific, in the United States, in Great Britain. And they wanted supplies to win the war. And they wanted opportunities for jobs and education when they came home. And Eleanor had been advocating since the early days of the war for legislation to support returning servicemen. And she really used the power of her public platform to help ensure that this was done by bringing pressure to bear on Congress, and by encouraging people to go talk to their representatives and tell them what their servicemen wanted. And so she kept hammering away at that, including after she came back from the Pacific. And the GI Bill of Rights was signed into law the next year. And the other thing that I think that we can see in Eleanor's trip to the Pacific are the seeds of her later work with the United Nations. She's operating on a global stage, she's advocating for peace. She's rallying as she's traveling through Australia and New Zealand, women in particular to be involved in civic life, to not sit idly by while men determine the fates of their countries, to use your voice and the power of your vote. And when she was in Rockhampton, Australia, the mayor there was giving an address and he said and he said he himself thought this and he figured he was not alone. But he that he would like to see Eleanor at the peace table. And because of circumstances that happened with FDR's unexpected death, Eleanor then went on to the United Nations. And I think that if he hadn't passed away, she probably would not have had that role. But it is interesting to see her operating on this global stage and of course, the words proved prescient of the mayor of Rockhampton.

Kelly 39:49

So this is an incredible book. Can you tell listeners how they can get a copy?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 39:54

Yes, you can buy it at most major online retailers. If you felt like it, you could put in an order at your local bookstore, it could be ordered. And there are also links on my website, which is ShannonMcKennaSchmidt.com.

Kelly 40:10

And there's an audio book too.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 40:12

Yes. In fact, I'm glad you mentioned that because the audio book has some bonus material on it. And it includes a speech that Eleanor gave to women at a theater in Wellington. And it's really, it's really special to hear that speech delivered by her in her words.

Kelly 40:32

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talk about?

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 40:36

No, I think that we covered a lot of ground and I thank you so much.

Kelly 40:41

Yeah. Thank you. I just, I really, really enjoyed this book. And I've always been a huge fan of Eleanor Roosevelt anyway, but I feel a real affinity to her. I think sometimes in this clearly, like, "got to do everything got to do as much as I can. What else can I get into this way?" I really appreciate that.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 41:01

Someone asked her, she was giving a speech after she came back. And someone in the audience asked her how many hours of sleep she got per night while she was in the Pacific. And she replied that she can get by on five but that she didn't always get them.

Kelly 41:16

Yes. Well, Shannon, thank you so much.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt 41:19

Thank you.

Teddy 41:22

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain, or are used with permission. You can find us on twitter or instagram, @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Shannon McKenna Schmidt is the author of The First Lady of World War II: Eleanor Roosevelt's Daring Journey to the Frontlines and Back (Sourcebooks/May 2023). She is also the co-author of Novel Destinations: A Travel Guide to Literary Landmarks from Jane Austen’s Bath to Ernest Hemingway’s Key West, 2nd ed. (National Geographic) and Writers Between the Covers: The Scandalous Romantic Lives of Legendary Literary Casanovas, Coquettes, and Cads (Plume/Penguin Random House).

In addition, Shannon has written for National Geographic Traveler, Shelf Awareness, NPR.org, and other websites and publications, including an Arrive magazine cover story featuring President Bill Clinton. She has been a guest on MSNBC's Morning Joe, Studio 2/WHYY, and the Travel Show with Arthur & Pauline Frommer, and has spoken at the FDR Presidential Library and Museum, the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College, the National World War II Museum, and other venues, including bookstores, libraries, museums, and historic sites.

From 2010 through 2017, Shannon traveled full-time—first in the United States by RV and then backpacking around the globe. She now lives in Hoboken, New Jersey.