The Long History of the Chicago Portage

When Europeans arrived in the Great Lakes region, they learned from the Indigenous people living there of a route from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, made possible by a portage connecting the Chicago River and the Des Plaines River. That portage, sometimes called Mud Lake, provided both opportunity and challenge to European powers who struggled to use European naval technology in a region better suited to Indigenous birchbark canoes. In the early 19th century, however, the Americans remade the region with major infrastructure projects, finally controlling the portage not with military power but with engineering, and setting the stage for Chicago’s rapid growth as a major metropolis.

Joining me in this episode is Dr. John William Nelson, Assistant Professor of History at Texas Tech University and author of Muddy Ground: Native Peoples, Chicago's Portage, and the Transformation of a Continent.

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is "Water Droplets on the River," composed and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons.

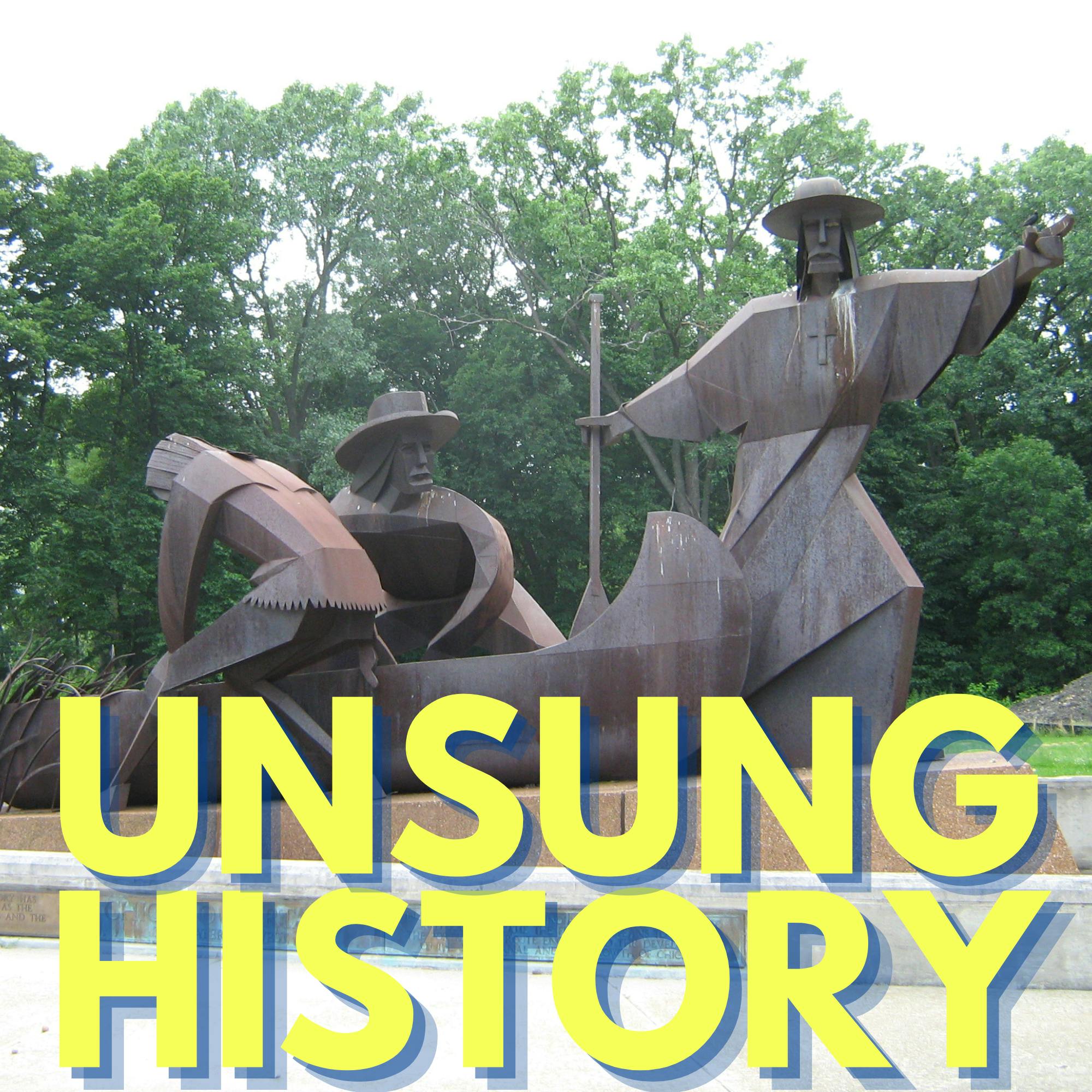

The episode image is a photograph of a statue that depicts members of the Kaskaskia, a tribe of the Illinois Confederation, leading French explorers Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette, to the western end of the Chicago Portage in the summer of 1673. The statue was designed by Chicago area artist Ferdinand Rebechini and erected on April 25-26, 1990. The photograph is under the creative commons license CC BY-SA 2.0 and is available via Wikimedia Commons.

Additional sources:

- “Chicago Portage National Historic Site,” National Park Service.

- “STORY 1: Chicago Portage National Historic Site/Sitio Histórico Nacional de Chicago Portage,” Friends of the Chicago River.

- “Portage,” Encyclopedia of Chicago.

- “The Chicago Portage,” Carnegie Mellon University Libraries Digital Collection.

- “Marquette and Jolliet 1673 Expedition,” by Roberta Estes, Native Heritage Project, December 30, 2012.

- “Louis Jolliet & Jacques Marquette [video],” PBS World Explorers.

- “Cadillac, Antoine De La Mothe,” Encyclopedia of Detroit.

- “Chicago’s Mythical French Fort,” by Winstanley Briggs, Encyclopedia of Chicago.

- “Seven Years’ War,” History.com, Originally posted on November 12, 2009 and updated on June 13, 2023.

- “Treaty of Paris (1783),” U.S. National Archives.

- “The Northwest and the Ordinances, 1783-1858,” Library of Congress.

- “The Battle Of The Wabash: The Forgotten Disaster Of The Indian Wars,” by Patrick Feng, The Army Historical Foundation.

- “The Battle Of Fallen Timbers, 20 August 1794,” by Matthew Seelinger, The Army Historical Foundation.

- “History of Fort Dearborn,” Chicagology.

- “How Chicago Transformed From a Midwestern Outpost Town to a Towering City,” by Joshua Salzmann, Smithsonian Magazine, October 12, 2018.

- “Chicago: 150 Years of Flooding and Excrement,” by Whet Moser, Chicago Magazine, April 18, 2013.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers, to listen too.

During the last Ice Age, around 10,000 years ago, retreating glaciers left behind a body of water that would become known as Lake Illinois, and then later, as Lake Michigan. The glaciers left behind more than just Great Lakes, however, with melting ice carving a series of rivers. To the west of Lake Michigan, the Chicago River drained east to the lake, while the DesPlaines River drained west to the Mississippi River. Between the two rivers was a wetland that some people called Mud Lake. Depending on the season, and the weather, Mud Lake could be dry enough to walk across, wet enough to canoe across, or anything in between. In winter, it might be frozen over. Regardless of the conditions, the portage provided a route to travel from Lake Michigan to the Gulf of Mexico, or spots along the way, for the Indigenous people in the area, who perfected travel by lightweight canoes that they could carry across the several miles of the portage. When Europeans began to settle in North America, the French claimed a swath of land, eventually stretching from Canada through the Gulf of Mexico and incorporating all of the Great Lakes. In claiming the land, the French were, of course, ignoring the many Indigenous nations who called the region home. In May of 1763, a fur trader named Louis Jolliet and a Jesuit priest named Jacque Marquette, armed with reports from local Odawa and other Natives, and joined by five mixed race voyagers set off from St. Ignace in what is now Michigan. They had been commissioned by the Governor General of New France to explore the region and search for passage to the Pacific Ocean. Jolliet, Marquette, and their crew, traveled from Green Bay, in what is now Wisconsin, up the Fox River to the Wisconsin River and then over to the Mississippi River, relying on Native guides to keep them from losing their way. They learned from the Illinois that the Mississippi emptied into the Gulf of Mexico, but fearing a run in with the Spanish, they turned around before they reached it. On the return trip, a group of Kaskaskia showed them a shorter route via Mud Lake, also known as the Chicago Portage. At the end of the journey, Jolliet headed to Quebec to report on their findings. His canoe tipped in the rapids of the St. Louis River, drowning some of his crew and destroying all of his notes and maps. Jolliet persisted, reporting from memory, and even suggesting that the French should build a canal at Chicago, connecting the two rivers to make the journey quicker. In fall of 1674, Marquette returned to the portage, planning to travel toward the Kaskaskia settlements, but an abdominal illness halted his progress, and the expedition ended up wintering over at the portage where Marquette kept a journal, recording for the first time in written record, life at the portage. Like Jolliet and Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, the commander of Fort deBuade in St. Ignace, Michigan, and later governor of Louisiana, saw strategic potential in the French controlling the Chicago Portage. Several French maps in the early 18th century, referenced Fort Chicago, but it was never to be. In 1717, French officials annexed Illinois country onto Louisiana, removing it from the governance of Canada. This realignment left the Chicago Portage as a border region, forgotten by both sides. In the 1763 Treaty of Paris, ending the Seven Years War, the French ceded both Canada and the portion of Louisiana east of the Mississippi, including the Chicago Portage to the British. Louisiana west of the Mississippi went to Spain. The Anishinaabeg, living near the Chicago Portage were not parties to the treaty, and had no intention of living under British rule. They attacked British traders who ventured into the area. Within two decades, the British lost the region to the Americans, ceding it to them in the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution. In July, 1787, the United States Congress of the Confederation enacted An Ordinance for the Governments of the Territory of the United States Northwest of the River Ohio, creating the Northwest Territory, which included the areas that would later become the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and the northeastern portion of Minnesota. In the next few years, in missions to investigate the region, several explorers learned of the geographic importance of the Chicago Portage. However, the Indigenous people in the area had no intention of allowing the Americans to take control. In 1791, the Confederacy of Native Americans decisively defeated General Arthur St. Clair and the US Army at the Battle of Wabash. George Washington demanded St. Clair's resignation, and appointed Anthony Wayne in his place. Wayne's victory at the August, 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers finally marked the end of the Northwest Indian War. At the Treaty of Greenville, Wayne attempted to gain US control of the Chicago Portage. He met with resistance, but managed to secure, "one piece of land, six miles square, at the mouth of the Chicago River." In 1803, the US Army used that stretch of land to build Fort Dearborn, named for then US Secretary of War, Henry Dearborn. During the War of 1812, Native American forces destroyed the fort in the Battle of Fort Dearborn. It was a victory for the Indigenous people, but a short lived one, as the US redoubled its efforts toward Native removal. In 1816, Fort Dearborn was rebuilt, but the real key to the US control of the portage was not military power, but engineering. The Americans built the first bridges across the Chicago River in 1832, began construction on an artificial harbor on Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Chicago River in 1833, and broke ground on the Illinois and Michigan Canal in 1836. These environmental transformations changed the balance of power in the region, removing any advantages the Indigenous people had once had. Joining me in this episode is Dr. John William Nelson, Assistant Professor of History at Texas Tech University, and author of, "Muddy Ground: Native Peoples, Chicago's Portage, and the Transformation of a Continent."

Hi, John, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. John Willam Nelson 10:11

Yes, thanks for having me, Kelly.

Kelly 10:13

Yeah, so I am super interested in hearing how you got into this topic, how you came to write this book.

Dr. John Willam Nelson 10:22

Well, I guess it's a two part answer. Right. So the, the standard answer we'll leave for a second, and that's kind of the dissertation research story behind this. But the first story is really kind of, I guess a little bit about me and why I was interested in this topic to start with. So the book is "Muddy Ground," right, and it's it's this kind of early history of Chicago as a portage, a canoe route that connects these waterways. And growing up in Ohio, I lived very close to the Great Lakes. So I was always fascinated with kind of the uniqueness of these these huge freshwater seas that are right here at our back backdoor as Midwesterners. And that really drew me kind of as a historian, but also as just a kid growing up in the Midwest. And I spent summers as a kid going to my family cabin up in Ontario, Canada, where we would do a lot of fishing and camping, but especially a lot of canoeing. And so canoe camping is the thing that happens in Canada, right, and canoe tripping, as they call it there, where you portage from lake to lake to lake to get into the backcountry. And so I grew up doing that with my dad and siblings. And that kind of was the personal spark that really got me interested in the significance of these kind of canoe routes and canoe networks that seemed to connect this region from, you know, the Canadian Shield to the Illinois prairie and everywhere in between. So that's kind of the first part of that answer. The second part of that answer is, of course, the more academic story, which is, I went off to grad school wanting to do early American history. And I went off to grad school already having this kind of portage project in mind, but I didn't know it was going to be about Chicago. So when I started doing the research, I was interested in the canoe networks as Indigenous creations in the Great Lakes, as both kind of an Indigenous technology right for fusing the region together, but also that as kind of this interactive space that both Native people and Europeans came to appreciate. So I had that in mind already when I went into grad school. But to be honest with you, that's a quite a project to bite off as a grad student, and my graduate advisor gave very good advice that I should narrow the project down, right. And he said, instead of writing about every portage in the Great Lakes, of every canoe route, and every potential meeting place between Native people and Europeans and canoes, let's focus it in on kind of a significant historical site that you can extrapolate out from, right, almost like a micro history of these canoe networks, and this kind of freshwater mobility from one vantage point. And the vantage point ended up being a perfect one at Chicago. And that's how kind of the story of "Muddy Grounds" started from kind of an academic idea and a personal idea into a doable and feasible and digestible project, not just for me to complete, but hopefully for readers to get through and and, and take something away from.

Kelly 13:40

Yeah, so I love the way you put it in the book that you're going to stake out this vantage point and sort of see history go by. So that sounds easy, in a way, right? Like you're gonna be in one place. I assume that the research is not easy, because there is not a single archive in which everything to do with the Chicago Portage is going to be. So can you tell me some about what that research looks like? What are the kinds of sources? This is multiple different nations have this region at various times, plus the early Indigenous time. So you know, like, what does this actually look like to do?

Dr. John Willam Nelson 14:12

Ya, no, it's a great question. And that's what really hooked me once I started to dig more into Chicago, I realized that not a whole lot has been written on it during the colonial period, during the early American period. And it's because it's not a site of European control, right? It is definitively under Indigenous control much longer than other sites in the Great Lakes that we might think of as important to early American history, so Detroit or Niagara, or Michilimackinac, right, these places that become fortified by Europeans, French and then British very early on, and generate their own written archives, right so you know where to go for the Detroit papers right? You know where to go for the for the papers from Fort Niagara. Chicago was not like that, because it's not a site of European power. It's a site of Indigenous power. And so it became a, a giant puzzle of tracking down scattered sources referencing Chicago and the canoe route running through Chicago, but not necessarily all collected into one specific archive. And so I actually did quite a bit of research on the ground and what I would call them kind of regional archives, and even international ones. So I spent time at the Library and Archives Canada, right, which doesn't naturally come to mind as a rich archive for Chicago, and yet, both between French fur trade documents and then eventually British fur trade documents that are flowing up through the Great Lakes, they end up in Ottawa, Canada eventually. So I spent time there. I spent time, minimal time, I will say, through digital archives in French and British sources. I spent a lot of time in Wisconsin and Chicago itself. So the Newberry and the Chicago History Museum, have managed to collect some local papers now, but it's kind of after the fact. So I did a whole year as a graduate scholar in residence at the Newberry that was really formative to the project. And it was great to write from Chicago. But I also then spent much time in Michigan and Pennsylvania and Indiana, kind of at these, again, regional archives, where there are historical sources collected there that are being generated from not necessarily from Chicago, but about Chicago. And that's really what I had to do to kind of pull these sources together. And at the end of the project, looking back, right, there's there's American sources, which are kind of the expected ones, but there are a lot of internal imperial sources too, so French, for the early period, British for kind of the Revolutionary period. And unexpectedly to me, I used more Spanish sources than I expect that I would have guessed, because the Spanish are in St. Louis, through, you know, the 1790s, almost 1800. Right. And they are generating sources, from from St. Louis, about the Illinois country and about places like Chicago as they interact with Native people there. So that kind of archival hodgepodge kind of had to be quilted together to make sense of this story. And then the Indigenous side of it only adds to the kind of the intrigue and the interest for me, because there are multiple Indigenous groups that live in Chicago, travel through Chicago, and for which Chicago is a very important site. And so figuring out that Indigenous history became a complicated part of this story too. And that goes beyond just archives, and that involves kind of ethno historical methods. So digging into the anthropology and the archaeology, and older ethnographies about Native people and their relationship to Chicago was important. One particular Indigenous person that really baffled me for a long time is this Indigenous Anishinaabe headman from the Revolutionary War era named Sigenauk. Right? And to get back at your archival question, this leader of the Chicago area Anishinaabeg, went by different names to different European powers, right? So the Americans always called him Blackbird. The British called him Sigenauk. The French called him Letourneau, which is kind of a rough translation of the starling or another kind of blackbird. And then the Spanish totally butcher it. They call him el Heturno just because it sounds like Letourneau. And so it took me a while to figure out that, hey, this guy is actually the same guy that the Spanish are talking about, the British are talking about, French fur traders are talking about, and Americans are talking about. They're just all referring to him in different names. And he lived in the Chicago area. So that kind of is a microcosm of some of the detective work that went into figuring out all of these different people talking about the Indigenous folks at this place, and then also the space itself from all of these different vantage points.

Kelly 19:13

So I want to talk some about these Indigenous groups. You mentioned, there are several of them. I live in Chicago. And so I have done that exercise of like land acknowledgement trying to figure out and it's hard in Chicago, because there's just a lot of different groups. So can you talk a little bit about why that is, why this isn't a place that there's just like a group that claims?

Dr. John Willam Nelson 19:32

Yeah, well, it's complicated history, because of Chicago as a crossroads, right. Part of what makes Chicago so significant to so many different Indigenous groups, is that it was long before Europeans arrived, kind of an intersection of interaction and an intersection of movement. So because Chicago sits at this low, low lying continental divide right between the Mississippi watershed and the Great Lakes, Indigenous people had been using this space as kind of an amphibious point of movement between the Great Lakes and the Illinois River Valley for centuries, and long before Europeans arrived, I think it was a crossover point, right. And the archaeology kind of hints at this, right. There are multiple overlapping kind of cultural signals in the archaeological record, even before Europeans get involved, then hints that there are kind of layers of Indigenous history here, and layers of Indigenous mobility here. That only becomes exacerbated once Europeans get involved, and these kind of cycles of violence play out between Indigenous groups, visa vie one another and Indigenous groups, visa vie Europeans. So, for instance, in the in the 17th century, right, that kind of the moment of French contact, there are multiple groups kind of traveling through Chicago without necessarily any one group living there. So you have reports of Meskwaki, or what are known as Fox Indians. The Illinois obviously are huge powerhouse downriver from Chicago. Miami speaking people are traveling through and kind of varyingly settling the area, off and on throughout the 17th century. And then by the 18th century, you have kind of more powerful arrivals, like the Anishinaabeg, who really come in and make Chicago part of their homeland. But that doesn't really happen until the mid 18th century. And so because of that, we have almost dozens of groups in which Chicago is significant to them, not necessarily just as a site of settlement, but also as a site of movement. Because again, this is kind of a no man's land crossroads for much of the the historical period where different Indigenous groups are traveling through Chicago, relying on its portage, relying on its kind of wetlands resources, but not necessarily living in the local area. And so a land acknowledgement becomes very complicated when you factor in that some of these groups are passing through, whereas other groups are trying to settle long term. And all of those groups see Chicago as significant to their life way. And so it's very hard to start arguing, "Well, is this Anishinaabeg homeland, is this Meskwaki homeland, is this Illinois homeland? It's all of the above, right at different times and in different ways, because of how they use the landscape and travel through it.

Kelly 22:33

So let's talk about that actual traveling, what the experience of going through this portage is, and why it worked so well for the Indigenous people and then maybe didn't quite work the way the French or Spanish or British or Americans would have hoped.

Dr. John Willam Nelson 22:51

Yes. This again, kind of goes back to that that story of Indigenous power and Indigenous technological advances, right. So Native people in the Great Lakes had kind of perfected canoe travel, without any input from Europeans. And when I say perfected canoe travel, I'm talking about lightweight birch bark canoes. These are canoes that had the potential to carry 10 or 12 people at times, along with hundreds of pounds of gear, if necessary, and yet were lightweight enough that you could carry these things between waterways. And the real advantage to the birch bark canoe is that wherever you go in the Great Lakes region, the very southern extremities being maybe the exception, there are birch trees growing, paper birch, right. You can picture the white birch trees that you can strip bark off and make repairs as you go. So in these accounts of Indigenous travel that we get from like Jesuit missionaries who are traveling with them or fur traders or early French kind of officials that observe the travel, Native people are traveling in these birch bark canoes, they'll pull into shore at night and they will make repairs almost on a daily basis to keep their lightweight birch bark craft shipshape and moving through the region. Now they didn't cross the broad lakes right. So don't picture birch bark canoes, you know, kind of losing sight of land, they kind of coasted along the sides of the lakes to avoid storms, they can rush to shore as needed if a gale popped up or something like that, but the real kind of genius of these things is though is the lightweight portability of them, and the fact that native people could if they knew the geography well enough, get to shore or get to the end of a river or get to kind of the stopping point of a body of water, pick up their canoe and carry it along with their gear to the net next watershed. And that's what makes Chicago such a vital kind of portage connection in this this network of mobility, because it is the lowest and shortest continental divide between the Great Lakes watershed and the Mississippi watershed. Native people kind of came to value it for its connectability. Right, you could sit at Chicago and in theory, only have a couple miles, you could carry your birch bark canoe, either into the headwaters of the DesPlaines of the Illinois River that would get you to the Mississippi and all the way to the Gulf Coast if you wanted to. Or you could go the other way, carry your canoe into the Chicago River drainage into Lake Michigan, and, and reach the Gulf of St. Lawrence, eventually, with a couple of short portages along the route. And so that's what makes it super vital to Indigenous forms of mobility. Of course, when the Europeans get involved, things change, right, so the Europeans almost immediately understand the strategic significance of a place like Chicago, because it is a connection point. It can unite the waters of the continent. That's how the French kind of describe the strategic geography of the area. What the French don't kind of master and I would say most Europeans don't for for most of the period I'm talking about in the book is, is this kind of Indigenous method of travel. So the French come in, and they immediately think they're either going to A.) build a canal here, or B.) dig a harbor and rely on kind of European shipping. Right? LaSalle is one of these early French adventurers who builds a European style vessel on Lake Michigan, with the plan of kind of connecting the Great Lakes through kind of a European Maritime network. And yet, it becomes difficult to have that reality play out on the ground, right. The portage as a wetlands landscape, always stymies kind of European efforts to master it. And the Griffin LaSalle ship goes down in a gale, breaks apart, we think on a sandbar in the Great Lakes almost as soon as it's built, and so that that vision of a French maritime empire in the Great Lakes never quite reaches fruition, because they're not quite willing to embrace the fluidity of these Indigenous forms of technology, the fluidity of these Indigenous networks of mobility, that hinge on birch bark canoes and and portages like Chicago.

Kelly 27:38

It seemed like such an interesting moment of like, how would history have been different? When the French are thinking about, maybe we should build a settlement or build a fort or something at Chicago? And then it seems like it the people in France are like, oh, we'll just split this region in two, we don't need to think about this as a central place. So can you talk a little bit about that? And you know, what, what it might have meant for the French if they had actually had, maybe they wouldn't have been able to control it, even if they tried to, but like, what, what that could have meant?

Dr. John Willam Nelson 28:09

No, it's it's really interesting, right? Because you do have as as historians, we never like to go counterfactual. But we don't have to in this case, because we have other examples of successful French fortifications and settlements elsewhere in the Great Lakes. So I think, you know, had the French followed through on this kind of advice from the periphery, if you will, right, as French officers are writing back and saying we need a fort at Chicago, we need a presence at Chicago, if they had followed through, and if they had somehow navigated the Indigenous geopolitics of the region better, and established kind of permanent presence at Chicago, I think Chicago would have ended up kind of going the the trajectory of a place like Detroit, right, or Mackinac, which become these kind of European hubs in an otherwise Indigenous landscape. Right. And it would have been kind of this this outpost of French power deep in the, the the interior, maybe kind of like St. Louis ends up being for kind of the Spanish era, or places like Detroit or Michilimackinac end up being for the French. But that's not the way it goes. Right. Like you say the French imperial wisdom of the day splits New France, which has becomes Canada and the Great Lakes from Louisiana and Illinois. And that boundary line goes right through what will become Chicago so that it really does become this kind of imperial border land or an imperial no man's land in between kind of French centers of power, meaning that that officials in Canada are happy to say, well, Chicago is your problem now. And people in Louisiana are happy to say well, Chicago is your problem now and it kind of falls through the cracks right? To the point where it allows both Indigenous resistors to find the space there for kind of much of the 18th century, but also clandestine smugglers. Right. So it's the only major portage route that is not fortified successfully by the French Empire in the Great Lakes region. And because of that, it becomes kind of a thriving hub of smugglers or what the French called courier Dubois, right, these woods runners that are basically illegally trading with Indigenous people against French wishes, which is really kind of interesting to think about, right kind of Chicago is this den of thieves? And, you know, Indigenous freedom fighters and all this stuff. Like it's kind of a romantic picture of mid 18th century Chicago, that I don't think we know a whole lot about, right? Because there's not a lot of records about it, except for these French officials complaining about it. But it does, it does kind of spark the imagination.

Kelly 30:59

I think Chicagoans would be very happy to claim that history.

Dr. John Willam Nelson 31:02

Yeah, exactly. Exactly. Yeah.

Kelly 31:05

So eventually, then, this is taken, this area is taken over by the British instead of the French and the British seem to have even less idea about what to do with this region. Like what did they just not understand that this was a potentially significant area? What what's happening with the British?

Dr. John Willam Nelson 31:23

Well, I think there's a couple things going right. So the British come in and claim this region by conquest after the Seven Years War. And for probably the first, I don't know, seven or eight years after they have claimed this region, they're trying to get a handle on it, right. And this is true, not just at Chicago, it's true at Michilamackinac and in Detroit, and throughout the Great Lakes and Ohio Country. And they have some severe setbacks early on, in the ways Indigenous people challenge their authority to this region. Obviously, Pontiacs War is kind of the famous example of this. But even after that particular war of resistance is over in 1763, this kind of low level violence that places like Chicago, or at least the threat of ongoing Indigenous resistance, that make the British very weak when it comes to being on the ground, right. There's a map in the book that I'm so happy to find, right, of a British cartographer who tries to map Lake Michigan, and he only gets to draw half of the lake because he's scared of the Indigenous people living in the other half of the lake, right. And like, so Chicago gets left off the British Imperial Map of the of the time, because Indigenous power is so strong in places like Chicago, and British claims are so tenuous. And of course, that gets compounded eventually, by the budgetary cuts of the British Empire, right, leading up to American independence. And then, of course, the actual moment of colonial rebellion means that the British are lucky to hold on to Canada, let alone places like Chicago, or the Illinois country. And so it very much is kind of this tenuous moment of imperial claims that quickly falls away, because the British are kind of incapable of expanding their imperial agenda this far inland, I think.

Kelly 33:28

And so then, of course, we have the Americans and Americans come in and do what Americans do and just say, "We'll just change the whole landscape. Make it work for us. This doesn't work for us. Great. We'll just change it." So can you talk a little bit about that, that different approach and how it from my view, it's successful? Right, I'm sitting here in Chicago, which is a bustling city, but you know, it's perhaps a interesting approach that they took.

Dr. John Willam Nelson 33:53

Yeah. Well, particularly interesting is the fact that it almost takes the Americans two tries to figure out how they're going to conquer this space. Right. At first they come in, in the 1790s. They claim this space as part of the Greeneville treaty sessions in 1795. And their plans initially are to follow French and British attempts at fortifying the the portage route. And so, you know, in 1803, they built the fort. And they tried to garrison and police movement through Chicago in the early 1800s. And this really backfires on them in kind of a very violent way, by the time we get to the War of 1812, when local Anishinaabeg, especially the Potawatomi of the Chicago region, are resentful of the American presence there and they use the war with Britain as a good excuse to, you know, attack the retreating American garrison and burn the fort to the ground, right kind of resisting that American presence. So that didn't work super well for the Americans, right? That kind of old imperial approach to how you're going to control this space doesn't play out well. So when the Americans come back in, in 1816, kind of first attempts and 1818, 1819, as statehood comes into effect, and an American presence returns to the to the portage, and the fort is rebuilt there, the Americans have kind of this new plan in play, right, that they're going to essentially rewrite the landscape. Eventually, they're going to dig a canal. But even before that, they're going to survey the land, they're going to measure out plots of land where they can dig this canal. They're going to plan out harbor improvements, so that it's no longer just a canoe river, you can get European style shipping into it. They they reroute the river, you know, 100 years later. And famously, they're going to redirect the flow of the river. So so the kind of engineering that makes Chicago famous really starts in the 1820s, as an American effort to say, "Okay, this Indigenous geography doesn't work for us, and doesn't work for the way we want to control this space. And so rather than simply conquering the Indigenous people that live here, we're going to, quote unquote, conquer space." Right. That's the kind of the famous John C. Calhoun quote that I use in the book to describe the American project of basically flooding this place with infrastructure, to the point where it's unrecognizable. It undermines the power of, of the Anishinabeg, right, this Indigenous, kind of local Indigenous presence that had controlled movement through the portage now finds themselves suddenly powerless or near there, because the environment has been reshaped, the geography has been reshaped. And now Americans control the landscape and the river and movement here and can call the shots. And that really is kind of the big shifting dynamic that kind of moves power from Indigenous people at Chicago to an American Settler state. Right. And by the 1830s, that shift has happened. And it's happened in kind of the most anti climactic way, right? This is not a big military victory. This is not a dramatic conquest of any kind. It is literally state backed infrastructure projects that undermine the geographic power of Chicago's Native people.

Kelly 37:32

Yeah, it's so interesting. I mean, it seems thinking like in retrospect, it's like, well, of course, Chicago is going to be a hub. It's this ideal location, of course, that you know, it was going to be a major city. But that was in no way obvious.

Dr. John Willam Nelson 37:44

Right? Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. It's not geographically determined in some way. Right? It is absolutely by chance, and by luck that the Americans pull this great coup off, right. Yeah.

Kelly 37:57

Coup against nature. Yes.

Dr. John Willam Nelson 37:59

Yeah, that's exactly what it is. Yeah.

Kelly 38:01

I want to ask a little bit, I saw on your website that you're thinking about your next project. And so I wonder if you could just briefly talk a little bit about, you know, sort of where you're going next.

Dr. John Willam Nelson 38:11

Yeah, so you know, this project was very place based. And, and I, I think different historians have different styles, right. And I think my style, as you as you research and write, you figure this out, and I am a kind of an in the weeds guy. And I don't want to say that too loud. But I do really like the particular and the specific, right. And so for this project, it was very place based. And I could focus in on Chicago and talk about these much larger processes that were playing out across the continent, but in this kind of contained localized space of Chicago. This next project, I think, is going to be contained in a different way. It's going to be about a specific group of people. And I stumbled on this second project, doing research for the first project. And I guess I'll describe the project and then I'll describe its connection to Chicago, because there is still kind of a Chicago connection. So I'm interested in the so called White Renegades of the revolutionary frontier, right, and this is the term that's used at the time to describe individuals who are essentially white settlers that cross over and end up living, and many times fighting with Native people against the incoming United States. And this happens kind of in the revolutionary moment in places like the Ohio Country, the Kentucky frontier, that sort of thing. But these individuals, these so called White Renegades, they they survived the era of the Revolutionary War, and they continue to kind of defy cultural expectations and racial allegiances, decades after our American independence. And so, as I was digging into the early history of Chicago, a few names like this popped up. John Kinzie is kind of the most famous right? There's, you can picture Kinzie Street and that Kinzie gets kicked around in Chicago history, right. But before Kinzie is lauded at this as this kind of white founder of Chicago, he's a blacksmith living in an Indigenous town in the Ohio Country, repairing guns for Native warriors that are fighting the United States, right? And his loyalties, even in the kind of Chicago era, John Kinzie moment, are sketchy at best, right? He's got some connections to British Canada, he certainly has connections to local Indigenous groups. He nominally claims US citizenship, but he's only one of these guys. And so several of them work their way through Chicago, Billy Caldwell would be another kind of mixed race individual that would fit this bill. William Wells, who famously dies at the Battle of Fort Dearborn is another person who would fit this kind of shifting allegiance over his lifetime. So I'm interested in exploring these lives, and what makes these individuals tick. So I've got kind of a handful of of eight or 10 of these folks that keep popping up in the archival record from the revolutionary moment forward. And some of them are women, and some of them are men, which is super interesting. Some of them are full on white settlers that go and fight with Native people. Some of them are inter married or of mixed race origin. All of them right kind of defy our expectations, and don't side with the US on the frontier, right. They kind of continue to be somewhere in between or vehemently in the camp of Native resistors in throughout the Midwest, throughout the Great Lakes region in Chicago itself. And so tracing their lives I think, will be a really kind of interesting, people based project to understand just how complex loyalty was in the borderlands of early America, how complex identity was in the borderlands of early America. And it kind of gives us a window to talk about the exclusionary efforts of the revolutionary moment on the frontier, while at the same time, recognizing that there are individuals that don't want to go along with that kind of racial exclusion that comes after independence. And that's really interesting to me.

Kelly 42:35

Well, I think everyone should go read "Muddy Ground," and especially if you love Chicago, and I know a lot of people who listen probably love Chicago. So how can people get a copy?

Dr. John Willam Nelson 42:46

So, it's available anywhere you buy books. There are, I know of several bookstores in the Chicago area, they have copies. And if they don't have copies, go to your favorite bookstore and ask them to order copies. It's through UNC press. So you can also of course, purchase the book at the University of North Carolina Press. It's available in hard copy and paperback, which is great. Of course, you can also get it on a ton of online vendors like Amazon, etc. So it's available anywhere you want to get your books, if you don't want to purchase it, you can also of course, implore your local library or your university library to buy a copy and get it that way. So yes, buy the book, read about Chicago. I am of course always available to answer questions. I love getting emails from people who have read the book already and are excited to ask me details about Chicago's early history.

Kelly 43:41

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. John Willam Nelson 43:45

Perhaps kind of the environmental side to all this, right? So I think Chicago's story is really interesting, not just because it's a story about American conquest and Indigenous dispossession. But also because it is wrapped up in kind of the environmental realities of that kind of colonial moment, but also, today's realities of kind of environmental concern, right. So when we talk about environmental justice, we usually talk about it in kind of 21st century context. And I think what the story of "Muddy Ground" tells us or hints at is that environmental conquest has always been part of kind of the settler colonial project, right? All has been part of the US conquest story. And we haven't necessarily always paid attention to kind of the environmental side of colonization. Chicago gives us great window to look at that because the US overhauls the landscape of Chicago in such a dramatic fashion, but this happens everywhere on the continent, right in different ways, where US settlers and the US state undermine Indigenous environments and weaken Indigenous power by doing so. And so I think that that type of environmental element is relevant even today when we talk about land acknowledgments at places like Chicago, an Indigenous presence at Chicago, the city today, and also the environmental concerns that that a city like Chicago faces in the 21st century, right. There are rising lake levels, there are sinking wetlands, there are flooded basements, and all of that has connections to this history. And that I think is worth paying attention to right and worth thinking about and kind of its long historical context because none of this happened overnight. Right. And it's all wrapped up together.

Kelly 43:58

Well, John, thank you so much. This has been great. I really enjoyed the book, and I've enjoyed speaking with you.

Dr. John Willam Nelson 45:53

This has been great, Kelly, thanks so much. You're a great host, and thanks for having me.

Teddy 46:20

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode, and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on twitter or instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

John William Nelson

John Nelson is a professional historian, teaching as a tenure-track faculty member at Texas Tech University. He specializes in the history of early America, with an emphasis on the borderlands of Indigenous North America and the colonial Atlantic World. His research examines the ways ecology and geography shaped the terms of cross-cultural interaction between Native peoples and European colonizers from first contact through the early republican era of the United States.

Dr. Nelson earned his B.A. at Gettysburg College in 2013 and his Ph.D. at the University of Notre Dame in 2020. His recent book, Muddy Ground: Native Peoples, Chicago's Portage, and the Transformation of a Continent, explores how a particular local landscape along Chicago's continental divide influenced colonial encounters from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. You can read more about the book and its forthcoming publication here.

At Texas Tech, Professor Nelson offers courses in United States history, Colonial America, the American West, Atlantic World, and Native American history.

Nelson has published work on the American West, Indigenous America, the American Revolution, and the environmental history of the Great Lakes region.