The Student Right in the late 1960s

In the late 1960s, as college campuses became hotbeds of liberal protest, conservative college groups, like the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists (ISI), the Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), and College Republicans, backed by powerful conservative elders and their deep pockets, fought back, staging counter protests, publishing conservative newspapers, taking over student governments, and suing colleges to remain open.

Joining me in this episode to discuss the campus right in more detail is Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd, author of Resistance from the Right: Conservatives and the Campus Wars in Modern America.

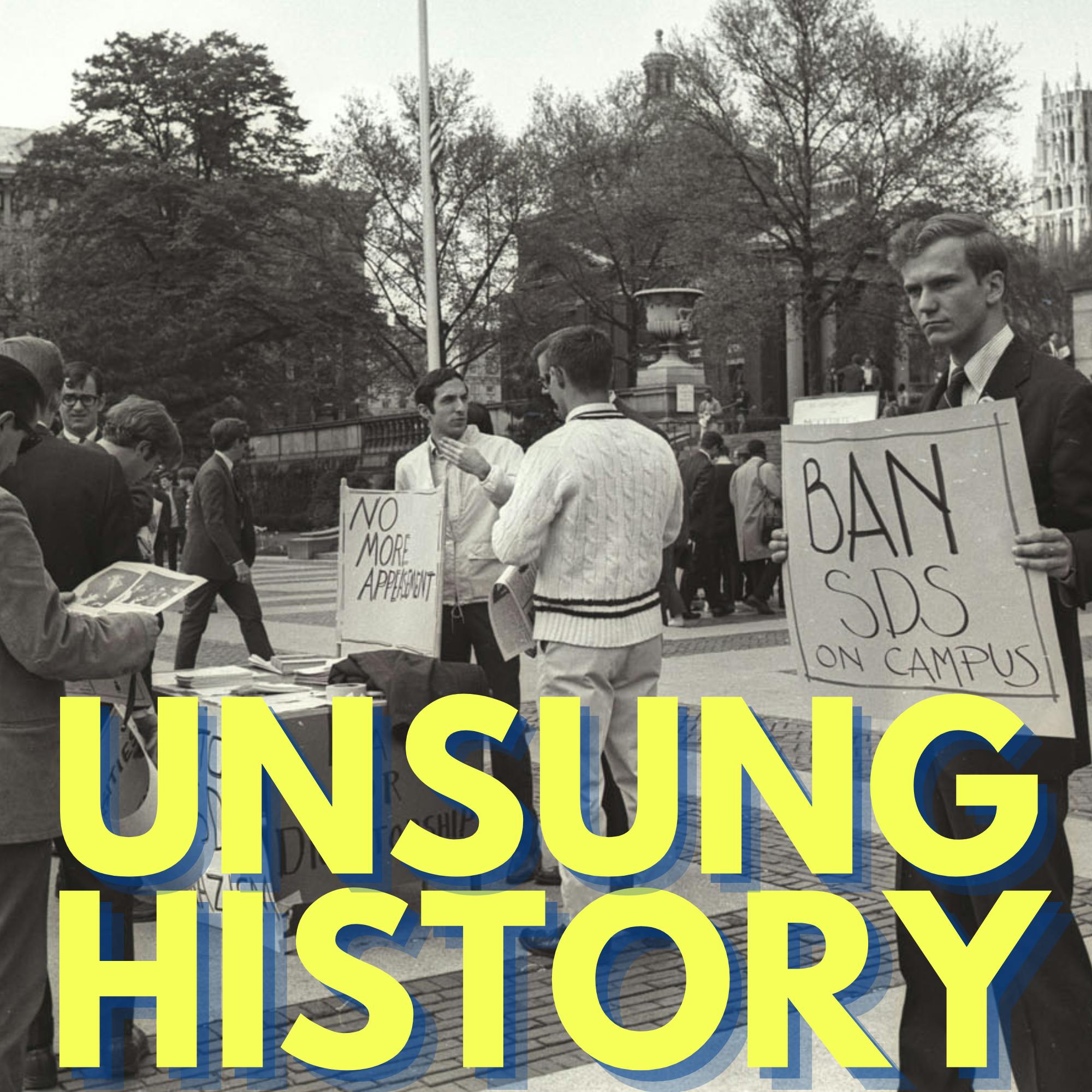

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “Row Your Boat,” by The Goldwaters, Sing Folk Songs to Make the Liberals Mad, 1964. The episode image is "Ban SDS sign,” Columbia University Student Strike, April 1968, Office of Public Affairs Protest & Activism Photograph Collection, Collection number: UA#109, University Archives, Columbia University, accessed October 9, 2023.

Additional Sources:

- “The Attack on Yale,” by McGeorge Bundy, The Atlantic, November 1951.

- “Debunking a Longstanding Myth About William F. Buckley,” by Matthew Dallek, POlitico, March 31, 2023.

- “About Us,” Young America’s Foundation.

- “Young Americans for Freedom,” Civil Rights Digital History Project, University of Georgia.

- "Young Americans for Freedom and the Anti-War Movement: Pro-War Encounters with the New Left at the Height of the Vietnam War," by Ethan Swift, Kaplan Senior Essay Prize for Use of Library Special Collections. 2019.

- “About Us,” Intercollegiate Studies Institute.

- “1968: Columbia in Crisis,” Columbia University Libraries.

- “How Columbia’s Student Uprising of 1968 Was Sparked by a Segregated Gym,” by Erin Blakemore, History.com, Originally published April 20, 2018, and updated July 7, 2020.

- “‘The Whole World Is Watching’: An Oral History of the 1968 Columbia Uprising,” by Clara Bingham, Vanity Fair, March 26, 2018.

- “The Right Uses College Campuses as Its Training Grounds,” by Scott W. Stern, Jacobin, August 2023.

- “Critical race theory is just the new buzzword in conservatives’ war on campuses,” by Lauren Lassabe, The Washington Post, July 7, 2021.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. In 1951, 25- year- old William F. Buckley Jr. published his first of many books. In the book, titled, "God and Man at Yale: the Superstitions of American Freedom," Buckley critiqued his alma mater, for what he saw, as indoctrination of students into the ideas of liberalism and socialism, with an enforced hostility to religion. "God and Man at Yale," put Buckley on the map of American conservatism, and within two years, he was the inaugural president of the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists or ISI. The ISI, backed by the deep pockets of the William Volker Fund, led programs on college campuses, to spread traditionally conservative ideals. In 1960, Buckley, who had by then founded the conservative magazine National Review, invited a group of around 100 young conservatives to his home in Sharon, Connecticut, with a plan to form an organization with a more activist bent than the intellectual ISI. The resulting organization was called Young Americans for Freedom, or YAF. On September 11th, 1960, the group adopted a statement written there by another Yale alumna, M. Stanton Evans. The Sharon Statement began, "In this time of moral and political crises, it is the responsibility of the youth of America to affirm certain eternal truths. We, as young conservatives, believe that foremost among the transcendent values is the individual's use of his God- given freewill, whence derives his right to be free from restrictions of arbitrary force, that liberty is indivisible, and that political freedom cannot long exist without economic freedom." The statement continued with another 12 principles about the role of government and the market economy, and asserting that international Communism was, "the greatest single threat to these liberties." YAF grew quickly, and by March, 1962, over 18,000 people attended a rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City, sponsored by YAF. At a time when there were conservative elements in both major political parties, YAF was nonpartisan. But members of YAF played a major role in the nomination of arch conservative Barry Goldwater as the Republican candidate for president in 1964. By the late 1960s, college campuses had become sites of unrest by the left, as students led frequent protests against the increasingly unpopular Vietnam War, especially after changes to the military draft in July, 1969, removed the deferment for currently enrolled college students. Anti war sentiments weren't the only cause that the student left championed. There was also a progressive push for diversification of both the student and faculty populations, and for the establishment of Black studies, gender studies and other ethnic studies programs. YAF, ISI, and the College Republicans, encouraged conservative students to fight back rhetorically, arming them with the classics of conservative thought, including Buckley's "God and Man at Yale," along with such books as "The Conscience of a Conservative," by Goldwater, "The Conservative Mind," by Russell Kirk, and "Capitalism and Freedom," by Milton Friedman. They did not stop at reading and classroom debates, however. What most united the various groups of campus conservatives was the opposition left. So one tactic they used was to organize counter protests against New Left protests. YAF was never as large as it claimed, in reality, probably only 15 to 20,000 students nationwide, but they coordinated their efforts with other groups who opposed the New Left, like athletes and members of the ROTC. In order to appear more popular, and representative of students than they were, college conservatives would often create additional clubs with new names, whose membership entirely overlapped with YAF or with College Republicans. On some campuses, college conservatives who were budding politicians, would take over the student government. Jeff Sessions, who would later be a United States senator, and then US Attorney General, began his political career as the leader of the College Republicans, and then president of the student body at the all white Huntington College in Montgomery, Alabama, from which he graduated with a BA in history in 1969. Conservative college activists had avoided physical violence, but that changed during a series of protests at Columbia University, in the spring of 1968. Left wing students at Columbia were, like students at a number of other campuses, protesting their university's involvement in research on weapons of war. At the same time, they were also joining community members in protesting a plan by the administration of Columbia University to build a student gym that would displace local Black residents from the neighborhood. At Columbia, the conservative counter protesters dressed in suits, including future US Attorney General William Barr, put their bodies on the line, surrounding a library where Students for a Democratic Society, SDS, was staging a sit-in. The goal of the conservatives was to block anyone from delivering food and supplies to the liberal protesters. Eventually, New York City police officers ended the demonstration. The college right pursued another tactic at Columbia that they then used at other universities, the use of lawsuits or the threat of lawsuits to demand that campuses remain open despite strikes and protests by liberal students. YAF, now called Young America's Foundation, still operates today. On its website, it claims to be the leading organization for young conservatives, with the mission to ensure, "that increasing numbers of young Americans understand and are inspired by the ideas of individual freedom, a strong national defense, free enterprise, and traditional values." ISI, now called the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, is also still running strong, with an aim to, "cultivate a vibrant community of students, faculty, and alumni, and teach foundational principles that are rarely taught in the classroom, the core ideas behind the free market, the American founding, and Western civilization." ISI claims among its alumni, Supreme Court justices Neil Gorsuch and Samuel Alito, and PayPal co-founder, Peter Thiel. Joining me now to discuss the college right in more detail is Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd, author of, "Resistance from the Right: Conservatives and the Campus Wars in Modern America."

Music 10:23

Hi, Lauren. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 11:28

Hi, thank you. It's great to be here.

Kelly Therese Pollock 11:31

Yes. So I am really interested to hear how how you came to be writing about this topic and why you focused in on 1967 to 1970.

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 11:42

Oh, sure. Okay, so this book started as my dissertation. And it came about actually, as a paper. I was taking a "History of Higher Education" course. And then we were, you know, covering the 60s, and hearing about all of the protests, like for peace and for making the curriculum more diverse and more representative. And I knew that outside of higher ed in the K-12 sphere, there's this well documented massive white resistance to integration and things like that. So I was wondering, like, what did that look like on the college campus? Where is this? It's not in the text. And I had a hunch that that didn't mean it wasn't there. And so, you know, I tried to read as wide as widely as I could. And I realized this, some of this is kind of included in some studies, but it's really kind of peripheral, there wasn't a focus study on the backlash from students themselves, especially white students, or students who were maybe veterans of the Vietnam War, who had come back or students who were in ROTC, and they were training to become officers to to go to Southeast Asia and fight. In another layer of context here, this was 2016, so we were nearing the presidential election. This is the fall semester, so, like campaigns were at the height at this point, and I knew that Trump in '68 would have been at Fordham. And so I was like, "Where is Donald Trump, the college student in the record?" And I couldn't find him anywhere. I mean, he didn't really seem to, play any sort of role in the campus wars. But I was I was just thinking like, there has to be, there's got to be other figures, right of his generation that and of course, I came to find out that there were lots of people that we recognize in politics today, right. Newt Gingrich was a part of all of this, William Barr, Jeff Sessions, both attorneys general. And so there's all of these names that I'm coming across. And I'm like this, I have to write about this, this. This has to be part of my dissertation. So a paper turned into dissertation turned into a book.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:43

So tell me a little bit about the sources that you used. And I know you did some oral histories for this. So can you talk a little bit about that and your your approach to doing this work?

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 13:54

Yes. So starting in the archives was kind of difficult for me. So as a grad student, I didn't have lots of funding. And I knew that Young Americans for Freedom's papers were kind of spread throughout the country. I mean, there's some of their papers are in Yale Sterling Library in the William F. Buckley Jr. Collection. There's some some other papers in the Hoover Institution, also the College Republican papers are there, attached to Stanford, so both coasts, and I was based in Mississippi, and without a lot of money to get there. You know, I had to do a lot of this online. And in fact, after the dissertation I did when I did actually have money because I had a job, I was able to enhance my own travel to these places to get some of the archival sources. So without being able to do that, as a grad student, I had to rely heavily on oral interviews and also very, very generous archivists who were willing to scan things for me and email them to me. So that was really helpful. But yeah, in terms of things I was looking for, I started the project out just looking for Young Americans for Freedom, which is one of the student groups who features prominently in the book, and there are a couple of others. So I was looking for YAF papers, I was looking for YAF newspapers. And when I kind of hit a wall, I thought, "Okay, I'll I'll reach out to these people themselves." I mean, many of them were in their 80s at the time, but they were very, very willing to speak with me, which was kind of surprising. I didn't know if they would want to talk about their their time as college activists or not. And so yeah, I interviewed like five dozen people who had been activists in the past. And so the project, in some sense, sort of became an ethnography, because I went to these people's homes. I'd, you know, sit down with them and have dinner with their wives, because most of them were men and their children, I went to CPAC. I went to lots of other alumni association events where I knew I could find, YAFfers and others. And so I conducted these oral interviews. And some of them were extremely willing to share their own artifacts with me. So if they had old newspapers, or old College Republicans materials, or old ISI, it is any sort of memorabilia that they had, they were really forthright in sharing that. And then I guess another major, major source of my sources was newspapers.com. I found a lot of stuff through, had a subscription to ancestry, and that gave me access to newspapers.com. And so I found a lot of a lot of papers that way. So I guess all of that is to say that these projects are doable on a grad student budget. You just have to you have to be resourceful, and and think far and wide.

Kelly Therese Pollock 16:34

Let's talk some about YAF, and how it started. And you trace in the book that this this is not just some sort of sudden spontaneous coming together of of students, that this is a really concerted effort. So can you talk some about the founding of YAF, what what it was, what it came together around, and sort of what it became during this time period?

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 16:56

Sure. Okay, so to begin with YAF is actually even to begin with, an earlier sister organization, which is Intercollegiate Studies Institute, or ISI. ISI was founded in 1953, and it was designed to be it was designed by movement conservatives, a lot of these like anti New Dealers from the 40s and early 50s, as a way to be like an conservative intellectual project. And so the very first president of ISI was William F. Buckley, Jr. And the first chapter was based at Yale. So anyway, ISI doesn't really do much. It's not an activist organization, it's much more focused on recruiting students, getting them really steeped in the intellectual literature on the right. And then from there, they can go on to become faculty or they can do whatever it is they want to do. ISI didn't really have those designs when it was first created in the 50s. So after less than a decade, only seven years, Buckley begins looking for students that he can recruit for an activist organization. So ISI kind of represents this intellectual youth wing of postwar conservatism. YAF is the activist arm. And so it was created in 1960. It was founded in September at Buckley's estate. And the name of the conference was the Sharon Conference, it was they met in Sharon, Connecticut. And they drafted their Sharon Statement, so their mission statement, and if you were to go to look at the Sharon Statement, it's quite concise. It's it's an easy read. It's short, one page, a couple of declarative sentences, and it's basically an anti communist document, right. You see lots of lots of statements about, you know, wanting to protect individual liberty and freedom and, you know, citing this communist menace overseas, because this is, of course, you know, we're deep into the Cold War. But it also has some elements of Christianity in there too. So when YAF first started off, it's it's this activist organization. And then, over time, you asked me earlier, why did I start this project at '67 to '70? That's because over time, YAF really really digs its heels in and to just combine those, right. So initially, one of the things that I argue in the book is that YAF, in from '67, to '70, doesn't have its own mission anymore, just completely banned, abandons the Sharon Statement, and it's more concerned about just fighting the left, whatever that means and whoever the left is. It's a very nebulous term and concept. So they kind of lose that initial like anti communist stance that they not that it goes away completely. They always harken back to it, but they kind of stray from their principles and they become more reactive and more reactionary, to the peace movement and to the students on campus who are seeking for Black Studies, programs or courses, or even just diversifying the campus right. I say in the book that the campus in 1969 is still 95% white, which is just incredible to think to think back on, or diversifying the faculty, right. These are things that YAF all becomes opposed to that have nothing to do with its principles as stated in 1960. So yeah, that's the decade of development of YAF. But of course, the organization is still around today as Young America's Foundation.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:24

So I'm interested in the the fault lines that kind of develop this, you know, that there's this kind of top down approach to creating things like YAF, but there are fault lines that develop in the 1960s, the Republican primary, for instance, who different groups are supporting, and then, of course, the split of libertarians, which we still see that tension today, of course, in the Republican Party. So could you talk a little bit about the the way these things kind of change over time, and when they're more successful, coming back together, or when they're breaking apart a little bit? Because it's an uneasy coalition sometimes.

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 21:01

Oh, extremely Yes. So in just those three years, '67 to '70, there's this constant making and remaking of the campus right, like it's constantly in flux. And that's because the students themselves are trying to do some organizing as much as they can, but they, they don't have the techniques or the skills that their elders have. And so what you see is from the post war conservative movement, and to be very specific, what I'm talking who I'm talking about, these are writers, people who are at magazines like National Review, Modern Age, and some other magazines that are kind of directing the students also in the the GOP, the Republican Party as well, that are directing the students on what to do how to organize. And so a lot of these fault lines are a product of the students themselves being maybe a little bit ideological. So we mentioned ISI earlier. ISI, when I talk about them in the book, that organization becomes like a an intellectual training ground. It's almost like a parallel university within a university. So these students are put together in these groups to study the great books and study rhetoric, and then come up with intellectual defenses for conservatism. And then they're funded by these movement leaders who are willing to cut big checks, that pays for their graduate tuition so that they'll go on to get PhDs or go to law school. Plus they give them stipends, because some of them are married and have families. So ISI is really focused on the intellectual parts. So ISI and YAF kind of brush up against each other all the time. And then there's this third group I haven't mentioned yet, but the College Republicans. So College Republicans are a partisan organization, right? They're not so they're not concerned about working with Democrats, whereas YAF is, has Democrats on its national board, right, Southern Democrats, people like Strom Thurmond, who who listeners will probably recognize and also several others. So again, the all three different major groups and there are more groups, they all have different ideas about what they should be doing on campus. So these mentors, these older conservatives, kind of forced them to get together under the least common denominator, and that is, we all don't like the left. Can't define the left, can't tell you who it is. Well, they can say who's in it, but you know, when it comes to when it comes to like the further extremes on the left, those people are easy to identify, right, like people who are members of Students for a Democratic Society or for students who are associated with like SNCC or the Du Bois Clubs on campus. Those enemies are easier to identify but even within their own ranks, so you asked about the the fault lines with libertarians. There's a chapter in,chapter seven in the book, called "Mickey Mouse William Buckleys." The libertarians at the 1969 YAF convention are purged from the group. And this is huge. This represents like a quarter of YAF's membership, which is really significant because YAF has spent years trying to position itself as a campus majority, a campus silent majority in the way that you know, this is '68, '69, Nixon's just run on his campaign representing the silent majority so they're doing that too but then they're purging a quarter of their members, and the fight is over a couple of things. So what happens at this '69 convention, libertarians are feeling some sympathies towards the peace movement, right? They don't like the draft especially that's the big thing. That's the problem for them. But they also are okay with decriminalizing marijuana use. They're against police brutality, because they themselves might have participated in some anti war marches and had to deal with police because of that. But YAF doesn't like any of this, right? So YAF, for as much as it's trying to build what they call majority coalitions and get these students together, it's also becoming extremely puritanical, right? So like the line is, "We don't have crossover with the left." And so because there are they're kind of squishy on these issues, libertarians are purged. This actually gets violent. I go into more details in this chapter. But you know, the the first night of the convention everyone meets, this is in St. Louis. So they all meet under the Gateway Arch. Buckley stands up and gives this introductory speech. And then you've got the libertarians, also represented with some radical anarchists who are screaming like, "F... the draft." They're booing Buckley. They're just creating a ruckus. And this is not going to end well. And so there are fist fights, kids bring the fights back to the hotels, they're like rumbling in the hallways of the hotels, not good. But anyway, so the libertarians are technically purged in the summer of 1969. But as I say, in the book, and as you alluded to just a moment ago, they're actually never really too far, because the traditionalists that who make up the majority of YAF and a majority of the right even today, still need to borrow some of those libertarian arguments, right? They still need those justifications, because libertarian arguments, even though they're about freedom, and they're, they're, they're concerned with maximizing freedom, but what actually happens when you play them out to the fullest extent, is inequality usually. And that's what the traditionalists inequality, that hierarchy of social orders what they want to preserve, so they borrow libertarian language, while turning their nose up at people who are libertarians.

Kelly Therese Pollock 26:30

So you mentioned that these movement elders are writers , that they're running publications, and that informs then part of the strategy of what they're mentoring, instructing, guiding these college groups to be doing as well. Can you talk a little bit about that media strategy, the the campus publications that are, you know, not exactly grassroots and what that looks like?

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 26:55

Yeah. Oh, I'm so glad that you said not exactly grassroots. Yes, I try to stress the point that this is an astroturf news site. Like, of course, there are students who genuinely you know, have sympathies towards conservatism. They're so orchestrated, they're so choreographed by their mentors. So the the example that that you asked about, normally, when we think of students campus publications in the 60s, we think we go straight to the New Left underground newspapers, right. There's no oversight from administrators, because they're totally underground. And you know, they're leaflets and students just pass them around. So the student right has their own version, and it's funded. I say it's underground. But a lot of times, it's funded directly by the trustees themselves who are sympathetic. And in one instance I talked about at the University of Southern California, YAF, and either solid Republicans or young Republicans, the other group kind of got together and had a close relationship with some of the trustees and used Presti donations to run the whole operation. And they just coded it as you know, alumni subscriptions. So the administrator's name wouldn't be attached to it. But I mean, they would fund the whole print run for a semester or a year or however long they needed to. And in terms of content, so the students themselves often did pen their own editorials. Or they would, you know, they would it would do their own investigation about whatever's going on on campus. But when they were short on copy, they could always just rip something directly directly from their mentors. Right. So College Republicans as an organization, they had these handbooks. YAF also had them, but they would be issued annually from the national office that said, like, "Here are articles that have run in GOP pamphlets or newsletters or whatever. Take them and use them. Keep this as a record, and so anytime you need to borrow something, like as an alternate fact, that expression, of course, didn't exist back then, but anytime you need some, some data to back up your convictions, you can just pull from things that we've already published." So yeah, there's that. And then National Review also was really, really good at working, people at National Review, so not just Buckley, but others are willing to read student drafts and comment on them and send them back, right. I mean, they're, they're truly like, this is really good mentorship. I almost wish something like this existed on the left today for our students, but I don't really know of any such organization. But yeah, I mean, they really, they, it's incredible, the structure that they built for these students to train them to mentor them. And then of course, they all go on to have long careers. All of the people I interviewed are in some way still involved in politics in their 80s.

Kelly Therese Pollock 29:45

So you mentioned earlier that before the the purge of libertarians, YAF has been trying to say it's a silent majority. It's trying to build up claim it's it's popular, and it seems at times like that's the goal is just to say like, "Look how just so many people agree with us, they're just not participating. But you know, they really agree with us."

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 30:06

Yeah, they're studying.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:07

They're busy studying. But at the same time, they seem to realize that in some ways it doesn't really matter how popular they are, if they can get on the side of the administration or the legislators, or they've got the president on their side, or that sort of thing. Can you talk a little bit about that, and in the ways that they're, they're really able to do a lot with not that much popular support among students?

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 30:30

Yeah, so the the book is divided into two parts. And the whole first part is about YAF just organizing, just trying to get its name out on campus trying to recruit members to its cause, YAF, ISI, and College Republicans, and Campus Crusade for Christ. But part two of the book begins with sort of a lesson that the college right learned after the 1968 Columbia demonstration. So if if listeners are familiar, there were two separate April and May two separate campus shutdowns, essentially, where students had occupied buildings. They were their grievances were over the university's involvement with the Department of Defense, and its aid to the Vietnam War. But also for this, this campus expansion,project, gym construction, they're trying to build a new gym gym facility that encroached in the neighborhood of Harlem. So for all these reasons, there's massive shutdowns of the university that that go on for weeks, the student right realized it doesn't have to actually like get involved and try to I mean, they do counter protests somewhat in the instance at Columbia actually gets really, really nasty. But they realize if they can just find who the authority figures are, and align with them and amplify them, then they can claim, "See, we represent the majority. We are, we speak for the wants of not only all of students, but also for the trustees and for the president and for the community itself." And there's actually something to that. They never, of course, represent the majority of students, but they often do do at times represent the feelings or the will of surrounding campus communities. We see a lot of instances where like Main Street business owners are really fed up with, you know, the peaceniks on campus. And that would be to, you know, cause trouble and, and things like that. So, YAF realizes, okay, it's not genuinely popular. It still goes on about, you know, purporting to be popular and to represent a silent majority. But it kind of internalizes this idea that as long as it is aligned with power, with powers that be, it has control in that way. So it can just, it can just say, "We represent everybody." And then look, here we are, you know, behind the scenes, having having things done and and another thing I go into in the book is, when YAF realizes that administrators may be, it may be that they are sympathetic with the campus left, YAF tries to force their hand. So one of the things that organization does is sue, or threatened to sue. Several institutions actually do sue, I think 11. They call for a court injunction and they're successful in a couple of them, not in most of them. George Washington University is a good example where they they sue either the president, the trustees, or maybe both. But they do get a court injunction that says, "Okay, you have to open the university back up." So and all they need is our small victories like that. You only need one, and to publicize that nationally, which they do. I mean, this small little campus group is able to write press releases and get it out there and get it into hometown newspapers. They're really being that way because they've got people who are guiding them to do so. That's another way that they seem to represent a majority. But yeah, even just the threat to sue administrators is often enough to make them say, "You know what? Maybe we need to just settle this down or compromise.

Kelly Therese Pollock 34:02

So let's talk a little bit about Kent State and the massacre that happens there. My parents were there. They were, they watched the ROTC building burn and they were thankfully not right in the heart of what was happening, but you know, on campus when the shooting happened. So this is an event that I've thought a lot about, but I hadn't I had realized I think that the that there was larger blowback outside of colleges that you know, there were there were plenty of people who were not college students who were not so happy with students and maybe thought that they deserved some of what happened. I hadn't thought as much about college right and how they might have responded. So I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the response of the college right. It's it's tricky, because of course, these are college students who have been killed. But what how did they respond to that? What what is their approach?

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 35:02

It's slow. So I'm sure your listeners are familiar with what happened at Kent State, but in in the aftermath of Ohio National Guard executing four students and harming several others who, who are I shouldn't actually even say students, they weren't all students, right? Some people were just spectaters at this at this protest that had extended on for several days. So anyway, after the death of the Kent State students, there's kind of this, well, there's a nationwide explosion. So at college campuses across the country, there are protests, sit-ins, lots of the campuses shut down completely because they had become so violent. So the way that the student right responds at first is with silence. And that's actually the direction they're given. So David Keene who had at the time, I think, was, if not the national director, he would be soon but anyway, he was he was still an important force. But David Keene tells students, "We just need to be quiet about this, right? Just let this unfold. It's summertime, right, because the the massacre happens at the early part of May, and the campuses are almost out for the summer anyway. And so it's like, let's let the summer pass. We'll pick up back, you know, with our with campus wars in after Labor Day," so the direction is to be quiet. But not all students follow that, especially at the University of Southern California that I spent a lot of time there talking about how students responded. So one sort of gesture that administrators nationwide take is to lower flags to the campus flag to half mast to honor the students. But there are YAFfers, Young Republicans on a couple of different campuses, Tulane is another one besides USC, who get in tug of wars, over lifting the flag back up, right. And so the justification from the right, is that this this is a political gesture.We shouldn't be doing this, right. This is an example of the administrators running amok playing politics. And, and so they can they can frame it that way to not have to deal with the issue at hand, which is that four people were killed by the state, right for for peaceful protests. We know that we know that the people who were killed, were either not participating, or they were they were at distances so far that they wouldn't have been the ones throwing, you know, rocks at the National Guard. So yeah, so yeah, you know, it gets combative on some chapters. But again, the national direction is to just be quiet about this, let it pass.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:32

Campus wars, of course, have not gone away. That's a hot topic in the news again. Could you talk a little bit about the importance for understanding this history that you've written about to understanding today and the culture of campus wars and cancel culture and all of that? What's going on today?

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 37:52

Yeah, I mean, so. So in a sense, it's a little bit different. So the story that I tell is about the student left and right. So it's about students. Today, we don't really see a campus left or right. I've thought so much about this, like who represent, of course, there's Turning Point USA on campuses, and there's Campus Reform, or some of those groups. YAF is still around. There's a Young Americans for Liberty, but they don't make headlines. They're not that big. And I don't know who the equivalent would be on the left. It's the closest thing I can come up with is, and maybe we'll see this as the as the '24 election approaches, maybe we'll see a new left group, but maybe some Bernie Bros. Like I just don't know who the left would be today. Instead, the campus wars are really GOP legislators versus the culture. I mean, there's no one direct it. They're not after administrators. They're not after students themselves. They they're after curricula. Maybe Maybe that's it. I know, in my home state of Mississippi, I'm keeping up with it really closely. Shad White. He's our state auditor, who is himself a Rhodes Scholar and has a master's degree from Oxford, most elite institution in the world, saying that, "You know, it's pointless that we have justice studies programs. It's pointless that we have arts and humanities programs." And it's just like, his master's degree is in social and economic history. So I know that he actually does understand this. He's just playing this, because a bit I don't know, but it has serious consequences for our students and for faculty. But another thing I can't be too far reaching with my conclusions, because really what we see when we look at like, take West Virginia, for example. That's not all from the right. That's also from the center, from liberals, right? You can you could call this neo liberalism, to say, "You know what, the money's just not there. These programs are not as successful. So it's just basic economics. It's just basic, being responsible with our budget. We have to we have to cut what isn't working." It is not driven by conservative ideology at all. That's, I guess, considered a moderate or responsible approach, but we know that that isn't true. Right, we know the importance of humanities. And so so like what's happening in West Virginia is a little bit different than what's happening, let's say, at New College in Florida, which is ideologically driven. Right. That's Chris Rufo, and the whole New Board of Trustees. And that's one of DeSantis' projects, and I'm sure there'll be others. So I mean, it's hard. It's hard to draw a straight line. Because again, the fight isn't between students anymore. It's legislators, it's people who control the purse strings and people who craft laws and have direct influence over higher ed policy and curricular culture, you know, whatever they're fighting about, and it doesn't look good. I don't end my book on a happy note. I don't end it on a sad note either, but I will say if listeners are trying to find something, the silver lining in this or something to be hopeful about, I think we've seen an incredible strike summer. People are joining unions, faculty are joining unions, grad students are joining unions. And I think that that is really, really important. It doesn't, it hasn't held a lot of success, like what we've seen at West Virginia University is not great. But in the California system, and I think New School was on strike last, the New School in New York was on strike last fall. So I mean, I'm trying to keep an eye on all of this. I'm very hopeful that organizing will help but you know, the most important thing that we could do to stop all this would be to get people elected to office who actually care about higher education and about learning and about open mindedness and just care about the academy, and are willing to protect it and to fund it.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:38

So if listeners want to get a copy of your book, so they can read for themselves this fascinating history, how can they get a copy?

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 41:46

You can find it anywhere books are sold. I can't believe I just said that. It sounds so weird. You can get it from the press website, the University of North Carolina Press carries it, also bookshop.org. Of course, it would be great if you could buy it from your local bookstore. And if they don't have it, please request it. If your institution doesn't carry it, please request it. And then or get Amazon, Barnes and Noble, all the places.

Kelly Therese Pollock 42:12

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 42:15

I think we've covered the high points today but I'm very happy to continue the conversation. If you want to talk more or if listeners want to talk more. You can find me, I'm still on Twitter, but also other places on the internet, @llassabe, or you can send me a note through my website which is LaurenLassabe.com.

Kelly Therese Pollock 42:38

Lauren, thank you so much for speaking with me today. I am really thrilled to have learned more about I'm have always been fascinated by this particular time period and I'm really happy to have learned more about it.

Dr. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd 42:50

Thank you. Thanks for the invitation.

Teddy 43:14

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources use for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episodes suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Lauren Lassabe Shepherd

Shepherd’s expertise is in the history of United States higher education from the 20th century to present, especially on the topic of conservatism in the academy. She is an instructor in the Department of Education and Human Development at the University of New Orleans and an IUPUI-Society for US Intellectual History Community Scholar.

Shepherd’s first book, Resistance from the Right: Conservatives and the Campus Wars, is out now from the University of North Carolina Press. Her second book manuscript is a historical survey of colleges and universities in the United States since the 1960s.

In addition to research and writing, she enjoys teaching Pilates and practicing yoga. She lives with her husband and their dogs in South Mississippi.

She can be reached at llassabe@uno.edu and on Twitter at @llassabe.