Project Confrontation: The Birmingham Campaign of 1963

In 1963, on the heels of a failed desegregation campaign in Albany, Georgia, Martin Luther King., Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference decided to take a stand for Civil Rights in “the Most Segregated City in America,” Birmingham, Alabama. In Project Confrontation, the plan was to escalate, and escalate, and escalate. And escalate they did, until even President John F. Kennedy couldn’t look away.

Joining me now to help us learn more about the Birmingham campaign is journalist Paul Kix, author of You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live: Ten Weeks in Birmingham That Changed America.

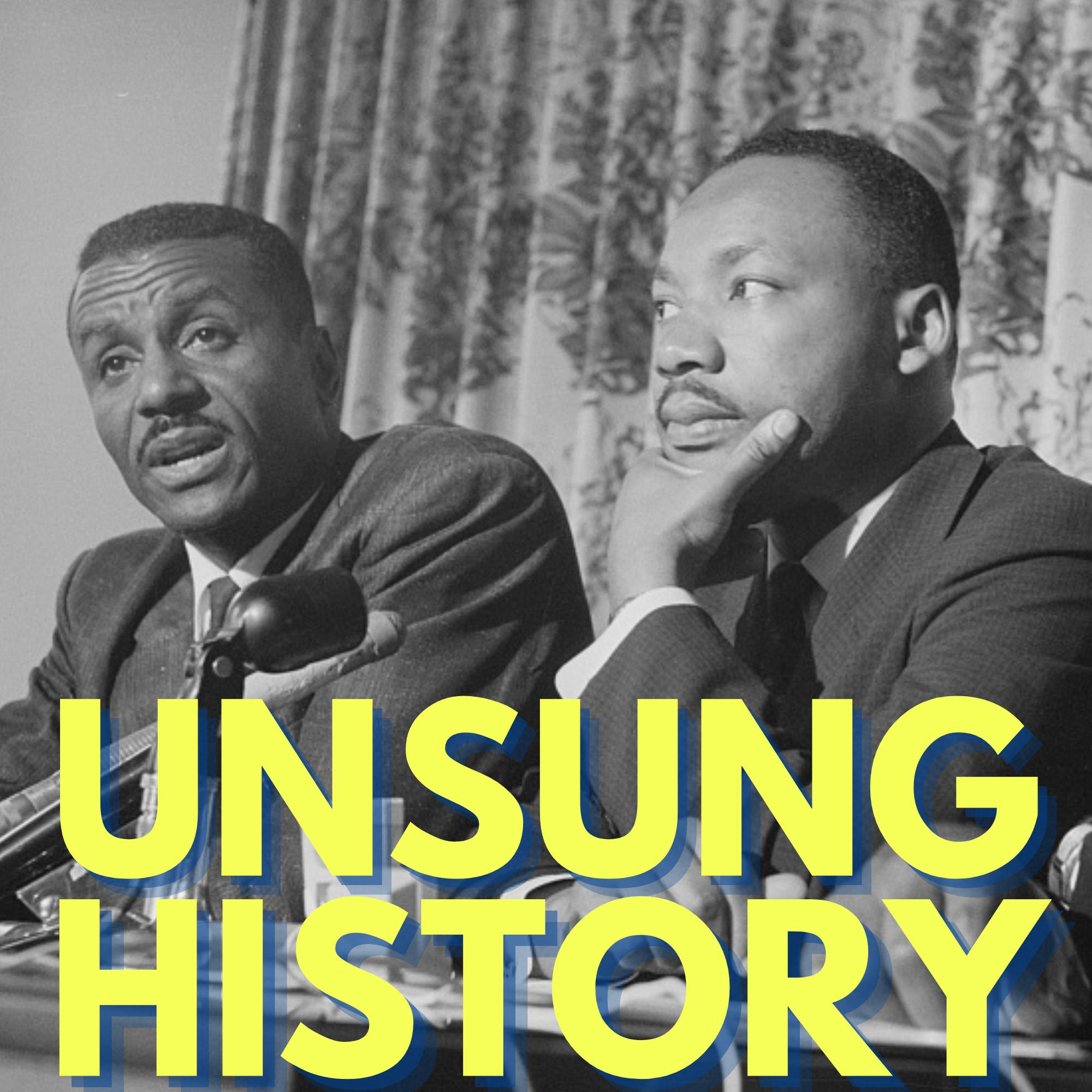

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “An Inspired Morning” by PianoAmor via Pixabay. The episode image is “Civil rights leaders left to right Fred Shuttlesworth and Martin Luther King, Jr., at a press conference during the Birmingham Campaign,” in Birmingham, Alabama, on May 16, 1963, by photographer M.S. Trikosko, and available via the Library of Congress.

Additional Sources and References:

- “Albany Movement,” King Encyclopedia, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University.

- “The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC),” National Archives.

- “The Birmingham Campaign,” PBS.

- “Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth (1922-2011),” National Park Service.

- “Opinion: Harry Belafonte and the Birmingham protests that changed America,” by Paul Kix, Los Angeles Times, April 27, 2023.

- "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," by Martin Luther King, Jr., April 16, 1963, Posted on the University of Pennsylvania African Studies Center website.

- “The Children’s Crusade: When the Youth of Birmingham Marched for Justice,” by Alexis Clark, History.com, October 14, 2020.

- “Televised Address to the Nation on Civil Rights by President John F. Kennedy [video],” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

- Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama: The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution by Diane McWhorter, Simon & Schuster, 2013.

- Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster, 1989.

- Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963-65 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster, 1999.

- At Canaan's Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-68 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster, 2007.

- Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference by David Garrow, William Morrow & Company, 2004.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. This week, we're discussing Project Confrontation, the name for the Birmingham Campaign of 1963, led by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, SCLC. In December, 1961, the SCLC had joined the Albany Movement, a campaign to desegregate Albany, Georgia, that the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC had launched the previous month. More than 500 protesters had been jailed by the time William G. Anderson called on Martin Luther King Jr. and the SCLC for help. The arrival and arrest of King and of second in command, Ralph Abernathy, did bring media attention to the Albany Movement; but after King departed the city in August, 1962, segregation remained. The Albany Movement was considered a failure. King later said, "The mistake I made there was to protest against segregation generally, rather than against a single and distinct facet of it. Our protest was so vague, that we got nothing, and the people were left very depressed and in despair." Tensions between the SCLC and the SNCC likely contributed to the disappointing result in Albany as well. By 1963, King believed that the SCLC needed to do something to jumpstart the civil rights movement, and there was no bigger goal than desegregating Bull Connor's Birmingham, Alabama, widely known as the most segregated city in America. The SCLC needed money, a lot of money to stage a major sustained protest, and King turned to singer, actor, and activist Harry Belafonte to ask for help. Belafonte hosted a swanky fundraiser at his upper west side Manhattan apartment, inviting his famous friends, including actors Sidney Poitier and Ossie Davis. With a rousing speech by Birmingham minister and civil rights activist Fred Shuttlesworth, who said of their audacity to stage a campaign in Birmingham, "You have to be prepared to die before you can begin to live." The SCLC raised $475,000 for Project Confrontation, the equivalent of $4.5 million today. Buoyed by their fundraising success, the Project Confrontation team prepared their plan for Birmingham. They ran into an immediate challenge. Bull Connor, an ardent segregationist, and opponent of the civil rights movement, had been the Commissioner of Public Safety in Birmingham for two decades, but the city had just replaced its city commission government, with a mayor council government, in part to oust Connor. On April 2, 1963, Albert Boutwell defeated Connor in the runoff of the mayoral election. Many in Birmingham wanted to give Boutwell a chance before rushing into protests. But Connor disputed the election results and remained police commissioner. The SCLC decided to forge ahead with the plan. The first protest happened on April 3, when African American activists sat at whites only lunch counters in five department stores in Birmingham. 13 protesters were arrested, but it wasn't the immediate splash that the SCLC had hoped to make. After a week of actions, there had been only 150 arrests, not enough to fill the jails that would generate the kind of response that the SCLC wanted. The plan, drafted by SCLC Executive Director Wyatt Walker, was to escalate and escalate and escalate. On Good Friday, April 12, King chose to escalate by joining the protests himself. King and Abernathy marched from the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church in Birmingham, and were quickly arrested. In jail, King was kept in solitary, but he was visited by an SCLC lawyer, Clarence Jones. Jones brought newspapers to King, and in the Birmingham Post Herald, King saw an op ed, written by eight white religious leaders criticizing the campaign and calling the protests, "unwise and untimely," while labeling King himself an outside agitator. King decided to respond, writing what would become known as the nearly 7000 word "Letter from Birmingham Jail." In response to the charge of the actions being untimely, King wrote, "We know through painful experience, that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor. It must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was "well timed" in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation." Even with the increased media attention from King's arrest, the Birmingham campaign was struggling, as many of the Black residents of Birmingham, understandably, feared reprisals, such as being fired from their jobs if they join the protests. SCLC Director of Direct Action and Nonviolent Education James Bevel, devised and initiated a daring idea: to work with a group who didn't fear such reprisals, the children of Birmingham. On Thursday, May 2, 1963, more than 1000 students, trained in nonviolent techniques by Bevel, skipped school and gathered at the 16th Street Baptist Church to march downtown. They left the church in groups of 50, singing freedom songs, and they were quickly arrested. As each group was arrested, the next group marched out of the church, filling the city's jails by the end of the day. The next day, Friday, May 3, Double D Day, another 1000 students skipped school and assembled at the church to march. Bull Connor was outraged and ordered their dispersal with fire hoses turned up high enough to knock them over, and police dogs attacking them. The SCLC finally had the media attention it needed to get the world to notice, and especially had the attention of President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. That evening, King said to the crowd, "Don't worry about your children who are in jail. The eyes of the world are on Birmingham. We're going on in spite of dogs and fire hoses. We've gone too far to turn back now." The crowd agreed and the Black community of Birmingham consolidated behind King and the SCLC. After repeated marches and protests, on May 10, King and Shuttlesworth announced that they had reached a deal with the city of Birmingham to desegregate public spaces, to hire Black workers in city stores, and to release those still in jail. Even with the agreement, desegregation in Birmingham, happened slowly and was violently resisted. But the events in the city inspired protests throughout the country. The events in Birmingham also convinced the Kennedy brothers that they needed to act. On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy, in a live televised address said, "Now the time has come for this nation to fulfill its promise. The events in Birmingham and elsewhere have so increased the cries for equality that no city or state or legislative body can prudently choose to ignore them." After Kennedy's assassination, a few months later, President Lyndon B. Johnson took up the baton, finally signing the Civil Rights Act into law on July 2, 1964. Joining me now, to help us learn more about the Birmingham Campaign is journalist Paul Kix, author of, "You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live: Ten Weeks in Birmingham That Changed America."

Hi, Paul, thanks so much for talking to me today.

Paul Kix 11:55

I'm so happy to be here.

Kelly Therese Pollock 11:57

Yes. So let's start by talking a little bit about why you wrote this book. You talk about it a little bit in the preface to the book. It's different than the other kinds of things you've written. So what was your inspiration?

Paul Kix 12:08

It was really my kids, in the end it was. So I'm a white man. I'm married to a Black woman. Our kids identify as Black. And it was actually the George Floyd's death. My wife Sonya grew up in inner city Houston, and she grew up in a neighborhood next to George's. George's was third ward, Sonya's was fifth ward. George was Sonya's age, 46, at the time of his murder. Sonya had cousins who went to Yates High, which is where George went to high school. In fact, those cousins remember George being the tight end on the football team that made it to the state championship games. So their histories overlapped, which is a long way to say that when George died, and the footage was shown on CNN, we did not shield our kids from it. The boys, we have twin boys, they were then nine, our daughter was then 11. And this was the first time we had done this with innocent Black people, predominantly men who had been killed by cops and their footage have been relayed either via body cameras, cell phone footage. So as a result of that the boys in particular had a lot of really tough questions about what exactly this meant. And I'll save some of that for the book itself about like what exactly they asked but I will say now that it was it was a sort of thing where they like this despair set in for the with the kids over the over the latter half of 2020. 2020 was a really hard time, like there were times where the boys would just leave the room in tears. Like there was another there was another man Jacob Blake, who was shot in the back by Kenosha, Wisconsin cops while his kids screamed from his car. And one of our boys was like, "Why do they keep trying to kill us? Anyway, it was soon something that Sonya and I really had to deal with. Sonya and I had both read a fair bit of the civil rights and civil rights movements memoirs, and, and what we found was like, what I found, I should say, especially as somebody who loved history, and has written history books before was that there was some period there was one period in particular, the 10 weeks of the Birmingham Campaign that I was just endlessly fascinated with. And anytime I'd have a chance, I'd explain it to people about why it was so fascinating. And that basically has to do with the fact that like the SCLC was broke going in to that campaign. They were going to easily the most racist, easily the most violent place in America. To give you a for instance, the police raped Black women in their patrol cars. The Klan castrated Black men. CBS's Edward R. Murrow, he goes down to Birmingham just prior to King arriving there. And he said that he had not seen anything like this place since Nazi Germany. So that was Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. And King and the SCLC, they go down there really and in Wyatt Walker's words, which was the executive director at the time of the SCLC, he said, "We will either break segregation or be broken by it." They really meant it, like this was their last ditch attempt. So I saw just for the purposes of story and story alone, something that was captivating but I also saw the more I researched it, not just a gripping narrative, but really like a guide for life, a guide for how any of us could live. And so ultimately, I committed myself to writing the book. This was so weird, Kelly, because, so there are great I should say, first off, there are amazing, like I can praise for the good chunk of this hour, the other civil rights books that are phenomenal, right. Taylor Branch's works, Diane McWhorter,s, I mean Garrow's stuff. I mean, the list is very, very, very long. However, in all of the time I had spent researching it, there was not, believe it or not,a single book that just dealt with the 10 weeks of the Birmingham Campaign, which I saw as absolutely critical, because what happens is, like there had been no national civil rights victories yet, in 1963. Montgomery Bus Boycott, sure, but even people in Montgomery were saying by 1963, that they were they were riding in the back of the bus again, as if it were like 1943, right. So they don't have any success. They're broke, they're going to the most violent place in America. And then after Birmingham, everything changes, right? It's because of that the the Kennedy brothers finally get aligned with civil rights that leads to the Civil Rights Act of '64, the Voting Rights Act of '65, Kings martyrdom in '68. And for somebody like me, I really and truly believe that what happened in 1963, allowed me to marry Sonya, in a former Jim Crow state of Texas. I've actually heard when I've told this to other people like, "Oh, that's not really true." It's like, well, maybe civil rights would have happened, but the same time, we went 100 years after emancipation with Jim Crow law in the south, right, like 100 years. What changes? The Birmingham campaign in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. Then everything changes. So I was like, I want to write this book for my kids with the understanding that, hey, here's, here's what I think is a 10 week period, the most critical 10 week period in the 20th century of America, that basically, you know, in some sense, gave you your life, right. And also, to bring it back to 2020, is really just, it is unbelievable how high the odds were how long the odds were, of them succeeding down there. And they were just, it wasn't as if they were completely like courageous the entire time. I should say that they were there are tons of doubt, there was tons of fear. There was tons of second guessing there was tons of sniping at each other. There were tons of there were huge egos in Birmingham among the civil rights leaders. But they came together and what they did literally changed America. So that is the guide for life thing that I wanted that I mentioned a minute ago. That's what I really wanted to try to relay. And yes, it was for my kids, but really coming out of 2020, and, and coming out of the pandemic, I mean, like, I don't know about you, Kelly, but like, I gave up on social media for a long time. Like, I'm just tired of the bitch fests all the time. Like I'm tired of how negative everybody is. It was infecting me. And I wanted to basically write a book that was like, "Look, if you just need inspiration in any way in your own life to do the work that you want to do, whatever that work may be, whatever your purpose is, right, let what happened in Birmingham be a guide for how you can lead your best sort of life. So that's really why I wrote it.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:37

So you mentioned a minute ago, the egos involved. So I want to talk a little bit about the personalities. There's so many big personalities, huge personalalities. There's the Kennedy brothers, there's Martin Luther King, there's James Bevel. Like these are really big personalities, and Bull Connor, of course. And that's such an important piece of the story and how it comes together and how they're playing off each other and making things work. Can you talk a little bit about that, about all these people who are involved in this in this such important 10 weeks?

Paul Kix 19:07

Yeah, so this was actually the thing that was most fascinating to me when I was deep into the research, because I don't know about you, but I had this sense when I was growing up that the civil rights movement was almost cast in this in this like, angelic preordained hue. You know, like, "Oh, this is going to work out, and all these people were great." These people were, not these people, these pastors of the civil rights movement, and the book is not just about King, it's actually predominantly about one of them, as you just mentioned a minute ago, James Bevel, and then also Fred Shuttlesworth, who I think should be as famous as King, as well known as King. He's a Birmingham pastor, and also Wyatt Walker plays a pretty large role in the book. He was then the executive director. So it's those three deputies and King. And the reason I'm talking about those three deputies in King is because they, Bevel and Walker pretty much hated each other, like openly despised each other, worked to undercut each other, and they're within the civil rights, they're within the SCLC. They are all pastors, by way too, right like, these are men of the cloth, who are acting very much like sinful human beings. And I loved, I loved that, because finally, like, let's show them for the flawed people they were because I think actually it's through our flaws that we end up sort of revealing our, our humanity. And that's what I wanted. That's why I spent so much time like, really letting the reader know, "Okay, here's who he is, here's kind of how here's the fight that he was maybe having with somebody else." Like there's huge class biases between somebody like Fred Shuttlesworth and Martin Luther King. I didn't pick up any of this in high school or college. You know, it was really once I got into the research is like, "Wow, this is fascinating!" A lot of the conversations we're having today, they were having, and a lot of the struggles we have today, they were having then.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:50

Yeah, I think too, I didn't realize really before reading this book, how much of an evolution Robert Kennedy goes through, over the 60s about race, about civil rights, about all of these topics. Could you talk a little bit about that evolution? Because it's so key to what's happening here.

Paul Kix 21:07

Yeah. So in some sense, Robert Kennedy is the character who transforms the most. He was at the outset, openly, somebody who said, "I am Jack Kennedy's protector," meaning that like if he did not fully trust Martin Luther King, and he did not, he thought there was he didn't understand why King was always trying to protest in the in the America that the Kennedys ruled. So if he couldn't trust him, he was not going to allow his brother to trust him at all. And, and openly suspicious, active, actively working against the civil rights movement and against the SCLC, in particular, across 1962 and 1963. And then what happens is, he starts to see, like, this idea of suffering becomes this huge metaphor. And what it means is basically like, it's a, frankly, it gives me goosebumps, just thinking about it right now, but basically, James Bevel, Fred Shuttlesworth, even especially King, they would talk about how if you are Black, and if you want to protest, and if you want to be a part of this movement, you must turn your body into a vessel. You must become a metaphor of the Black experience itself, meaning that you are going to get beaten by a Bull Connor, his Klan friends, and the cops. And you must allow this because if we allow this, then perhaps a New York Times reporter will scribble notes about it, or Walter Cronkite's camera crew will film it. And then the hope was the Kennedy brothers would watch that, and then do the thing that King and everybody else in the SCLC, and really the whole of Black and to a certain extent progressive America wanted, which was real and lasting civil rights legislation. Kennedys were completely, Bobby in particular, completely against it, prior to the spring of 1963. And what Bobby in particular saw over that spring, transformed him. The images that he saw from Birmingham transformed him and he became, he became the SCLC's biggest advocate. In some sense, the the sponsorship that the Kennedy brothers ultimately offered in June of '63, the sponsorship of civil rights legislation was Bobby's doing, Bobby convincing Jack that this is something that he needed to evolve to as well.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:07

Yeah, fascinating. So let's talk a little bit about the reaction of the people of Birmingham, the Black people of Birmingham, when the SCLC decides, you know, they're gonna come in and they're gonna, they're gonna help but you know, it's almost like the they're like, Yeah, this is great. But you know, we're not we're not quite sure where, like, you're coming from the outside. We know this town better. Like, what, what, what's going on here?

Paul Kix 23:59

Yeah. Here's another part that was sort of a minute ago about the angelic hue of, of history. Here's another part where it was just like, "Wow, I did not know it was this complicated." Basically, Black Birmingham did not want what it called the "Interlopers from Atlanta," which is where the SCLC was based, coming in, and, again, openly worked against the SCLC. It was led by a Black Baptist ministers conference that was just so chilly and frankly, in King's words, awful to the SCLC. He called them brainwashed at one point, and this is to their face, like that's how contentious it gets like in meetings. And then you had then you had, you got people like A.G. Gaston. A. G. Gaston is fascinating. He is, he owns a Gaston Motel in in Birmingham, and it's one of the few that's open to Blacks. Like world class entertainers are coming through the Gaston Motel. He also owns a couple banks. He owned by that point, a small college. He was well on his way to becoming the richest Black man in America, and one of the richest in America, period, at the time of the of what's what's called Project Confrontation, those 10 weeks in Birmingham. So he was, he wanted nothing to do with it. He thought what the SCLC planned to do was awful, and part of the reason was because, and I can almost understand this, because so there was this election, just prior to the SCLC starting and it was between Bull Connor, who if you if you know a little bit about the story, you may have heard that name Bull Connor, the Public Safety Commissioner sort of virulently racist, fairly close ties to the Klan, runs his police department like the corrupt official that Bull himself is. And basically like Bull was going to, Bull was running for mayor against the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce's guy, Albert Boutwell, who was a sort of dignified racist, and and as a result, like Boutwell wins and people like Gaston, and the Black Baptist Ministers Alliance, they're like, "Well, look, the to the extent that Black people could vote in Birmingham, and there was a small proportion of people who actually could, they voted for Albert Boutwell. Albert Boutwell talked, talked about, "Hey, we're gonna have a equality." King and the SCLC were like, "That's probably not real." But it came off really sanctimonious for King and the rest, Wyatt Walker in particular, to basically proclaim that we kind of know what's best for you. That pissed off people like A.G. Gaston too. You know, like, "Who are you? Like, you haven't lived here your whole life." You know, I just anytime like I actually, Kelly, love to read. I don't know that, I don't know if this is like the word for it. But like, I guess I call them small histories or contained histories, like periods where you can just go super deep on a few weeks. Like I read this amazing book probably five or six years ago, gosh, now I'm gonna blank, just on the assassination of Lincoln from the perspective of the assailant, John Wilkes Booth. Gosh, I wish I could remember that name. Anyway, fascinating book. And that book, like when I read it, like six, seven years ago, I was like, "Oh, that'd be so cool to do that." And then finally, when I started to piece together, "Well, maybe I should do this book on Birmingham." I had that John Wilkes Booth book, in mind with a few other ones were just like, "This is so cool." When you can just go super deep on just a few, again, a few weeks, a few months, whatever it is, because it really acquires that texture, that even great books, like the ones I mentioned earlier on the civil rights movement, just because there are these, and there's I should say there's I have nothing against those books, but like, because they're trying to be exhaustive and everything they're covering, they can't go super deep on just one issue. They have to go, "Okay, well, we've spent 50 pages on this campaign. Now we have to move to the next," right. But there are I found in researching Birmingham, there are entire worlds in Birmingham in those 10 weeks.

Kelly Therese Pollock 27:51

So one of those things that's happening is, you know, the there's some resentment that these interlopers are coming in and they're getting a little bit of traction from the adults in Birmingham, but not a lot of traction. Not a lot of people are following them. They're not filling the jails like they're hoping to. And then it's it's James Bevel who says, "I've got an idea." This is audacious! Can you talk a little bit about using the children?

Paul Kix 28:16

This is, this was known, so it's Project Confrontation is the name of it, and then a sort of subtitle is, "The Children's Campaign." And basically Bevel, James Bevel, for those who don't know, he was, I would say, I'm gonna say arguably the youngest member of the SCLC. He was then in his 20s at the time, completely idiosyncratic dude. The guy wears, he wears overalls everywhere he goes to sort of like in honor of his native Mississippi and this sense that even though he's a pastor, he did not put on any airs. He actually wore a yarmulke, and he would did that because he thought that he was half Jewish. He actually likened himself off of some profits from the Torah. And people in the civil rights movement called him the prophet because he tended to speak in sort of these Old Testament dictums like, "Thus saith the Lord said of James Bevel," right. So like, dude, this dude is out there. He's kind of he's, he's his own man. And what James Bevel does when he gets to Birmingham, is he's like, "Well, I see a problem here. Black adults, Birminghamian's don't want to protest, because basically, they would get fired by their white bosses for doing this." And it's not even just like, domestic workers, right? It's people who are viewed as you know, more white collar. There were teachers whose white superintendent would be like, as soon as you protest, you lose your job. There were Black lawyers in Birmingham, who first had to just even fight to be admitted to the Alabama bar, and then argue their cases in Birmingham's courts. And now somebody like King is coming in and saying, "Yeah, we want you to protest," and these lawyers are like, "Are you out of your mind? I'm not, there's no way I can do this. I won't be able to feed my family after you're gone." So there's again that interloper thing, right, like I'm here, you're from Atlanta. Bevel's from Mississippi, and Bevel, maybe because he's a sort of, he's a sort of ideologically, as conservative as some of the people in Birmingham. He kind of understands these people like he's from the same sort of rustic environment as a lot of Birminghamians, and so he's like, "Okay, well, if the problem is are the adults? What if I got their kids to protest?" And the SCLC was like, "You are out of your freakin mind, like that is insane. You're going to send these kids into what Edward R. Murrow called a couple, you know, just before we arrived here, like Nazi Germany, like they're going to be the front line?" And Bevel's basically like, "Well, yeah, like protesters are protesters. You've got to have them." And King fought it for the longest, longest time and so did Wyatt Walker, who again despised James Bevel, but ultimately, even Wyatt Walker, who was huge on publicity, on getting media attention to Project Confrontation was like, he was basically like, I mean, the images would be, this would be amazing, right? I think viewed only through the through the lens of how grotesque they would be it to see Black kids going up against Bull Connor's cops, that would be on the front page of The New York Times. That would lead Walter Cronkite's broadcast for sure. And so ultimately, Bevel won and and that's like, leads right into like, May 1, May 2, May 3, and Double D Day, and everything that happened there.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:35

So you mentioned earlier, you have kids. I have kids. The thought of like, I understand the symbolism, I understand the you know, all the reasons that they they sent these kids out here and I totally understand why the kids were like, "Yes, of course, we will do this." As a parent, it's hard to imagine like the thought of your own child being you know, water hosed or bitten by a dog.

Paul Kix 31:59

Yeah, it's, it's, it's so the here's a here again, is something where we've probably seen these images on TV of like the water hosed kids. But I just want to place that in context. These water hoses were mounted on effectively like huge, massive, almost artillery style tripods, because the force of the water that gushed out, was enough to knock mortar loose from bricks, was enough to knock bark loose from trees at a distance of more than 100 feet. And you see, actually some of the images that you don't see like in school, or in any documentary, I saw some of the raw footage. It is grotesque. Kids are back flipped in the air, their clothes, more or less disintegrate on them. I mean, one girl I'll never forget this in one of the clips, one girl, she is writhing in pain and these Birmingham firefighters keep the hose on her, and effectively, like she slides down this Birmingham street 50, 60, 70 feet now writhing in pain and just screaming in terror too about like, "How much are they you know, how much longer are they going to push me like this right?" Then there's kids getting attacked by dogs, right? One kid was attacked, probably eight, nine years old attacked right around his throat. There's a very famous image of a of a kid named Walter Gadsden, who is kind of like, kind of like a somewhat modern context, if you know the falling man image from from 911. There is this sort of open body, like Gadsden in that photo is just like relaxed, it looks almost serene, even though it's a grotesque image. And I talked about a little bit in the prologue. And there's this there's this own fascination with why I loved the Birmingham Campaign because of that image as well. I thought it captures the whole of America in that one image. But like the Kennedy brothers saw that and they were just like, "I can't believe that this is what is happening in America." And it was so bad in early May, that Birmingham cops were coming up to King and saying, "You've got to call off this protest. We can't keep this going." And King was basically like, "I've had enough." Bevel was like, "Okay, now we'll bring 'em in." So there was this, I say that because it's like, there was this, again, this understanding that your body will become a vessel for suffering, your body will become a metaphor for what is basically what has been for the longest time, the Black experience itself. And there is also for the people who are carrying this out this sense of callousness. So for certain parents to see this, it was so hard. There was one parent, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and the Birmingham Public Library, they are so I mean, I got access to so much some of that a lot of stuff. were oral histories that have never been in any book form before. They've been, they've been recording over last 20 years, all of these are oral histories with everybody that was basically a part of what happened in '63. And there was this one dad I'll never forget. And he was like, he was a member of Fred Shuttlesworth's church, so like on the front lines of being willing to protest. And the interviewer asked him, I'm gonna paraphrase it was something like, what was it like when you saw your son getting fire hosed? And they normally in the oral histories, they don't they just have the answer. But whoever actually typed it, they actually said, very long pause, like, bracketed it very long pause, right. And then the dad said, it was one of the hardest things that I ever had to witness. And he was watching it that day from like, you know, maybe 100 yards away, there's, I ended up using that quote, again, I'm paraphrasing that quote, but that quote, does appear in its actual quoted form, in the book. But that was the experience, right? Like, there were parents who were furious with King if he allowed that. And King, like Bevel, they had to have a certain callousness to what they just allowed, because they're like, it almost has to happen this way. Like, Wyatt Walker used to say, "Everything must escalate in this campaign. Everything must get consistently worse." And that was there was like, "Okay, we're gonna use kids, and they're gonna get attacked, and we have to be fine with this." And the kids were, but their parents weren't.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:20

Yeah. So I do another podcast where I talk to political activists about, you know, sort of what what can you do? How do you use the skills that you have? And so of course, one of the skills that Martin Luther King Jr. has, is this ability to think and to write and so one of the things that comes out of this 10 weeks is when he's in jail, he is writing furiously on whatever scraps of paper he can find. Can you talk a little bit about that, and his ability to sort of take this terrible situation, he's in jail, he's in, you know, solitude, and turn that into something incredible?

Paul Kix 36:54

Yeah. So he to set this up a little bit, thank you for that. So he is, um, he goes to jail at a time when he thinks that if he's in jail, the camp the Birmingham Campaign might, might be snuffed out, because he has no idea if he's going to be there for six days or six months. And...

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:17

He has a newborn baby that he has left!

Paul Kix 37:20

He has a newborn babyat home. Everybody that has protested with him thus far, they don't know what's going to happen with King in jail, who's going to step forward. And if anybody else wants to protest, while he's in his in prison, they too, will be put in jail for up to six months. So it is this huge leap of faith. And I mean that in the personal sense, and for King as a pastor in the Christian sense, to say, "Okay, I am going to go into jail." And so he says, in his first night that never has he been in a dungeon like that. And then what he meant wasn't just the confines of solitary confinement, like this was arguably the worst night in jail that he ever experienced, that first night in jail. Second day in jail, he gets this op ed, from eight or so different Birmingham clergy, some of whom had had taken positions with him in the past, to end segregation. And basically, they're like, they're basically making an interloper argument. They're like, look, we really feel that it would be in your interest if the citizens of Birmingham just looked tried to resolve this on their own. And, you know, you're basically and you are through your actions, you are making things worse, as if, as if entice, like, he is basically enticing Bull Connor to act and that really upset King too. It upset King, that these, these people of faith would reach this conclusion. And it upset him that, that he was the reason that Bull Connor was acting the way he was when instead, he wanted to show that Bull Connor was going to act this way, regardless, right? And he was going to argue that white America, the south was going to act this way regardless. He just wanted to basically chronicle it. So he goes, he's in jail. And he reads this op ed, and it's his lawyer, Clarence Jones, fascinating character in his own right. And Clarence is like, "Okay, we got to talk about like, basically how to keep this campaign alive." And instead King's like, "I have to respond to this," meaning the op ed. And so he just grabbed scraps of newsprint. And over this course of, I think it's about seven days, he writes this searing, soaring piece of rhetoric. It's amazing. He's quoting Socrates, Jesus, Martin Bieber. He's quoting all these, he's quoting all these people from memory. And what I tried to do in the book was show his own intellectual and spiritual evolution with respect to nonviolent protest and just basically how to live because he started his life as an intellectual in his college days in a vastly different position than where he was by the time he's in the Birmingham jail. In some ways that transformation is as big an arc as what Bobby Kennedy goes through over the spring of '63. And King's sort of intellectual understanding was something that I tried to really put on the page because King himself puts it all in his letter. And the letter, of course, ultimately becomes "The Letter from Birmingham Jail." And for me, Kelly, like, I mean, like, as a writer, myself, and as somebody who for, you know, I'm 42, I've spent probably 15 of my 20 plus professional years also, as an editor, the back and forth between King and Wyatt Walker about what they should include in the letter, what should, what they shouldn't like, oh, my God, that was so much fun! It was, it was one of my favorite parts to research one of my favorite parts to write. And for me, it was one of those periods where I was just like, you think you know what this thing is, "The Letter from Birmingham Jail," but there's actually again, a whole world behind it, a whole intellectual, psychological, spiritual world behind it. And I wanted to try to bring that to the fore.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:19

Yeah, I'm the kind of writer that like, I need to have all of my sources around me as I'm writing, and I'm constantly referencing them. So the thought of just like sitting there, like paper and a pencil, and that's it, and you're writing is just amazing.

Paul Kix 41:33

And it wasn't even it was like an early, so Clarence Jones, when he finally gets when, when King finally gives him enough hints that like, I'm not going to talk about the campaign while I'm in prison until this letter's done. Clarence Jones finally just relented like, okay, so he brings him like, actual paper. But before that King was using, like toilet paper, and scraps of newsprint. That's how the letter began. And he's using all these arrows all over the place, you know, this, this line goes to this idea. And it is this is like, it's all it's all chicken scratch as Wyatt Walker later said in trying to figure it out. So oh, my gosh, I loved, I love that part of the story!

Kelly Therese Pollock 42:08

So let's talk a little bit about measuring success in something like this, right? Because they, they get to the conclusion, you know, at some point, these are people from outside, they need to leave. So we need to sort of reach a conclusion. But it's hard to know, as they're leaving, if they have really achieved what they meant to achieve. And you know, we can look back from the point of view of history and see it but you know, at the in the moment, you know, it seems like there's even among the leaders of this a little bit of a disagreement, like "Did we get everything we should have gotten?"

Paul Kix 42:38

Yeah, huge disagreement, a very precarious state. And here's where we were mentioning, we were talking earlier about sort of class distinctions between somebody like King and somebody like Fred Shuttlesworth. So Fred Shuttlesworth is a Birmingham, pastor. And Fred thought, basically, by the end of the Birmingham Campaign, when a letter to an agreement to fully to at last desegregate, was put in place, he thought, basically, that King had duped him, because it fell far short of what they had all thought was going to happen, for going down to Birmingham and trying to start that campaign. And he thought he was Shuttlesworth wondered, I don't know if it's fair to say he believed openly, but he kind of wondered aloud if what all of Birmingham was was ever just a platform for King's own national grandstanding. And so this agreement is in place, and it's immediately precarious. There's like, well, the white authority immediately does everything it can to undercut it. And so then King has to like, come back and try to make the best out of it. But even then, there's no real sense that this is going to hold. And then it kind of spreads and it goes everywhere. And then it's then then it becomes, I mean, if you are a person of faith, this is where the story becomes a little bit supernatural, a little bit miraculous, because you're like, "Wow, how did this happen?" And it's basically, in some sense, you know, people were inspired by what had happened in Birmingham, Black people in particular, and they wanted to try to execute a similar vision in their own cities, a lot of them southern cities. And it's, it's in some measure why I wanted to write the book, to show like you were mentioning activist before, I'm not an activist, per se, I always have been much more of a journalist. But however you choose to act in life, if it's just nothing more than moving toward what you see as your purpose, you know, like you don't know exactly. Like the lesson of Birmingham, one of the lessons of Birmingham for me is you may have a grand plan and they had a grand plan in Birmingham. They had it meticulously, Wyatt Walker was the most meticulous dude you could possibly imagine. He had it literally timed down to the second. How long it would take certain people to get from a church to a downtown sidewalk to protest? None of that matters when it actually started. So what what matters instead is, do you have faith in yourself? For these men of the cloth, do you have faith in God, that this is actually going to work? And then do you have faith, that after you have to use what you were just talking about ago, a quote, victory? Well, what happens after that? Do you still hold the faith that the world that the world now will see the way see things the way you do, that the world will kind of bend toward your vision. And this is one of those instances where it did. And it's just, it's even now I got a little bit of goosebumps, because I'm like, Wow, this actually works.

Kelly Therese Pollock 45:36

So that we don't spend 10 weeks talking about these 10 weeks, but we probably could, tell people how they can get this book, which I will mention is an incredible read reads like a novel. So I...

Paul Kix 45:46

Oh, thank you, thank you. Yeah, I think they the it should be available, basically, anywhere books are sold. You can go go online as well, to try to get it. "You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live," super long title. But it comes tries for me to sum up the precarity of those 10 weeks, the faith that it took. A lot of times when you think about the Civil Rights Movement, you think about like some grand, almost biblical phrase. I wanted this to be far more rooted, far more visceral, in its title. And that title is actually a quote that comes from a man I now admire deeply, deeply, deeply, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, one of the lead protagonist in the story. So "You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live."

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:34

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Paul Kix 46:38

As I was putting this together, and putting it out into the world, I thought a lot about well, I thought a lot about like, we are in a point in America, where there's a question about why like a white guy like me should be writing a book like this. And what I what I turn to is just this notion of, I think, my own the fact that I am the head of a Black household and have been for, you know, 15 plus years now is part of that answer. But what I really want people to take away from is right now the political extremes are such that it feels like the identity politics of the far right and the far left is sort of putting in place an almost retrograde in retrograde segregation. I talked about this a little bit in the, in the epilogue to the book, and my kids notice it now too. And there again, Birmingham is a guide, like getting, at one point, in April of that spring, there are white racists in the pews, attending one of his sermons, which is basically like a mass meeting to try to get more volunteers. And there's also people who were Black nationalists, and thought that, you know, basically, like there should be an enforced segregation. That which in some sense, mirrors some of the far left identity politics about like, segregating ourselves from one another, looking only through the prism of race to understand each other. And King, King said that he wanted to live in a world, this is in Birmingham, where little white boys could go to school with little Black girls. And these kids, white kids, Black kids could play together, swim together, love one another. And then he said, "Yes, I had a dream tonight" And it was about this dream. And King would use that speech just a few months after Birmingham on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in the in the summer of 1963. But he uttered it, he uttered it, but just before that in Birmingham, and that's what I really want Americans to keep in mind, right? Like we are more than our skin deep identities. And you know, we can we can always strive to be more. I just, there is something so, when I read that, I just I almost cried because it was just like, oh, he captured that. I mean, like first, you know, the significance of what's going to happen a few months later. But the fact that like he's identifying this 60 years ago and saying like, "No, no, I, I actually don't align with the with the Black nationalists here. And just as much as I don't want white people to separate themselves. Like that's not a path forward for us." And we are in a much different place today, a much better place, like Sonya and I can raise our kids on a shaded street where nobody harasses us for who we are. That's huge. That historically that did not happen in America, we this is incredible progress. And I just hope that people who consider themselves progressive in one way or another, keep that in mind, that you know you don't want to ever get to the point where there is this segregation of a sort. So anyway, that's that's the last thing I would like to say.

Kelly Therese Pollock 50:06

Oh, Paul, thank you so much for joining me. It was, I really enjoyed reading your book and hope people check it out.

Paul Kix 50:13

Wonderful. Thank you so much can I have it really enjoyed it.

Teddy 50:16

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Paul Kix

Hi, I'm Paul Kix, a writer who loves to tell big beating-heart stories about larger-than-life people in precarious situations. The men and women who live through these experiences often have the best sense for the universal truths of life, and I've become obsessed over the years with not only the drama of these characters' existence but the wisdom they've gained. I've tried my best to relay that wisdom in my magazines pieces or in the pages of my book, The Saboteur, which DreamWorks optioned for a movie, and my piece for GQ, The Accidental Getaway Driver, which was turned into a major motion picture.

I've also had the good fortune of shaping other writers' work at ESPN.com, where I'm a deputy editor. These are often writers whose compassion drives them to do their best work: Pulitzer-Prize winners like Eli Saslow and Don Van Natta, Jr.; the poet and MacArthur "Genius" Award winner Claudia Rankine; and Wright Thompson, acclaimed (not only by me!) as the best sportswriter working today.

When I'm not writing I'm teaching a digital course I created, The Storytelling You, or helping clients with their writing and storytelling projects.

Born and raised the son of a fourth-generation farmer in Hubbard, Iowa, I now make my home in Connecticut, with my wife, daughter, identical twin boys, and mother in law.