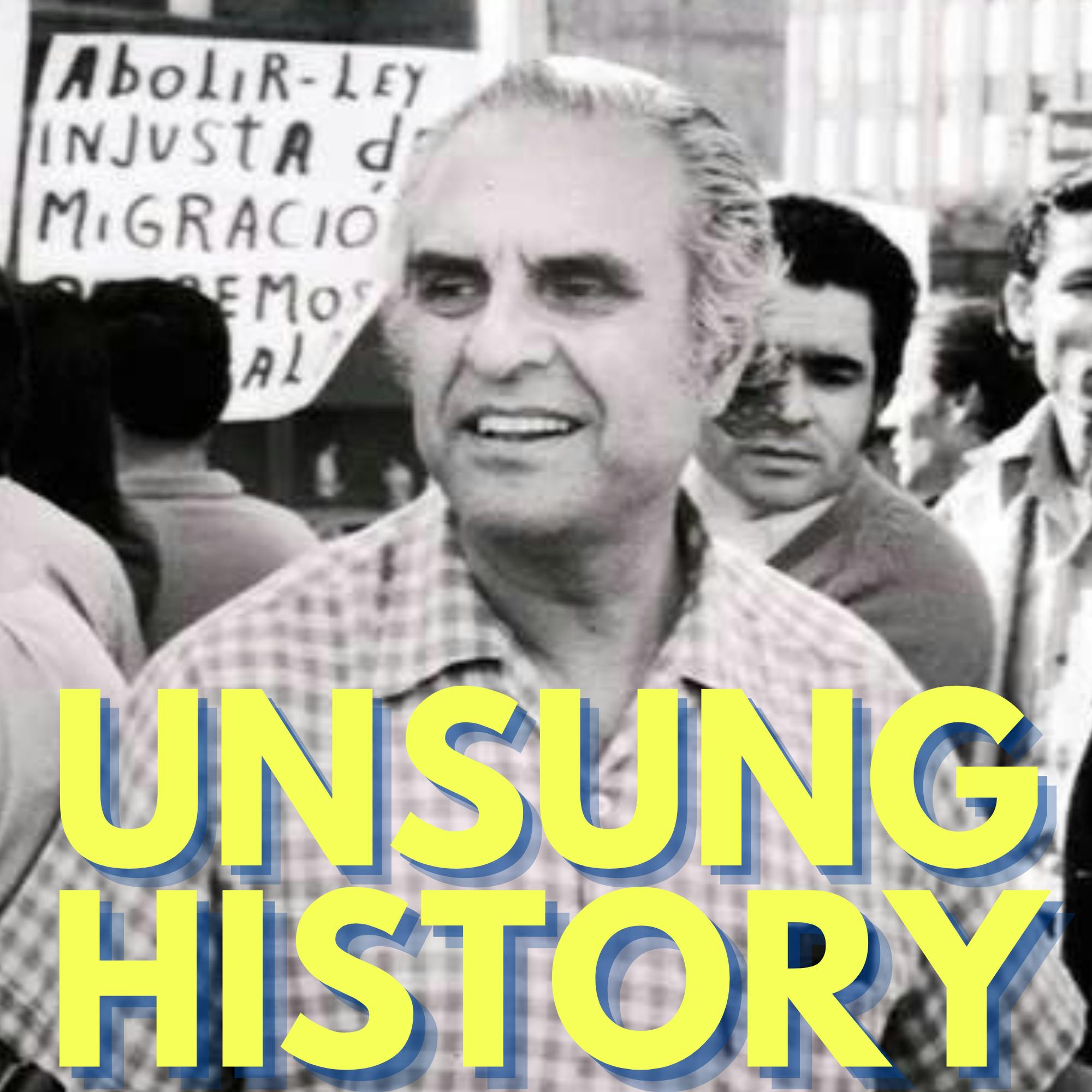

Bert Corona

Labor leader and immigrant rights activist Bert Corona viewed Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants in the United States, both with and without documentation, as one people without borders, and he understood that their struggles were connected. While other Mexican American labor leaders were campaigning against undocumented workers, Corona fought to shift the opinions of Mexican Americans toward support for the undocumented and helped create a pro-immigrant consciousness among Latinos in the United States.

Joining me to help us learn more about the life of Bert Corona is Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Kentucky, whose 2019 dissertation looks at the roots of the Immigrants’ Rights Movement and who has written and taught about Bert Corona.

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image is “Bert Corona,” source unknown, believed to be available via Creative Commons.

Sources:

- “‘One People without Borders’: The Lost Roots of the Immigrants’ Rights Movement, 1954-2006,” by Eladio B. Bobadilla, Duke University PhD Dissertation, 2019.

- “From the Archives: Bert Corona; Labor Activist Backed Rights for Undocumented Workers,” by George Ramos, Los Angeles Times, January 17, 2001.

- “The Legacy of Bert Corona," by Carlos Oretaga, The Progressive Magazine, August 1, 2001.

- “Remembering Immigrant Defender Bert Corona,” by Eladio Bobadilla, The Progressive Magazine, February 7, 2022.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. Today, we're discussing labor and immigrant rights activist, Bert Corona. Humberto Noe Corona was born on May 29, 1918, in El Paso, Texas. His parents were Mexican immigrants. His father, Noe Corona, had fought in the Mexican Revolution. In the United States, Noe Corona continued his involvement in revolutionary activities. The family briefly returned to Mexico in 1922, but when Noe was murdered, possibly by the president's forces, Bert and his family returned to El Paso. Bert's mother, Margarita, pulled him out of public school in the fourth grade, when she was frustrated with the treatment of Mexican kids who were punished for speaking Spanish. At the Harwood Boys School in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Corona organized what he later called his first strike when he and other boys refused to attend classes, until their demand was met that students no longer be spanked for questioning their teachers. Corona returned to El Paso for high school, where he became a basketball star and won an athletic scholarship to the University of Southern California. In 1936, having an athletic scholarship meant that Corona was recommended for a job where he could work nearly full time while in college. In his case, the employment was at the Brunswig Pharmaceutical Company, and it was there that Corona found something that interested him more than basketball, as he became involved in the labor struggle. When the longshoremen's union wanted to organize farmworkers in Orange County, Corona volunteered to help. He recruited union members, and in 1936, led 2500 Mexican American and Mexican workers in a strike. Having found his calling in the labor movement, Corona left college and took a job as a union organizer with the Congress of Industrial Organizers, or CIO, where he organized workers in the canning and packing industries. In August, 1941, Corona eloped and married a Jewish American labor organizer named Blanche Taff. When the US entered World War II, Corona volunteered for the Army Air Corps. When he was done with basic training, and officer training, during which he witnessed racial discrimination, Corona went to California for flight training, and worked 16 hour days, both training and doing clerical work. In California, Corona was given a psychiatric evaluation designed to root out so called deviance, and then he went through rounds of interrogation as officers questioned his political activities. With no explanation, Corona was dismissed from the Air Corps and assigned to mailroom duty in an army hospital. He later trained as a paratrooper. Just before he was set to deploy overseas, he requested a pass to go to Atlanta. The pass was issued, but improperly, which Corona later felt was purposeful; and as a result, he was locked in a federal prison for 45 days without pay, while his unit shipped out.

After World War II, Corona returned his attention to the plight of Mexican Americans and undocumented Mexican immigrants. He joined forces with union leaders Phil and Albert Usquiano to found la Hermandad Mexicana Nacional, or the Mexican National Brotherhood to support immigrants and organize workers in San Diego. In 1968, Corona co-founded Centro de Accion Social Autonomo, or CASA with Soledad Chloe Alatorre. CASA provided practical help to Mexican immigrants, especially undocumented immigrants, by teaching classes on reading and writing in English, along with history and driving courses. CASA, as a community based organization, acted much like earlier Mexican mutual aid societies. But CASA also had another goal: to help convince Mexican Americans to support undocumented immigrants and to show that they were one people who should join forces in their labor and social efforts. In 1974, Corona worked with immigrant rights activist and Catholic priest Mark Day, to write the Charter of Rights for Immigrant Workers, also called the Immigrant Bill of Rights, that they presented to the United Nations. In the document, they argued that immigrants had as human rights, the right to job security, equal pay and access to labor unions, along with freedom from deportation, and the right to unite with their families. Corona distributed the document widely, which helped to shift the opinions of Mexican Americans towards support of the undocumented. Corona had left college before earning his degree, but his life experience was so valued, that he lectured at colleges, including at Stanford, and at several Cal State campuses. Teaching at Cal State Los Angeles in the 1970s and 80s, Corona led a group of adjuncts who were pushing for social activism to be part of the mission of the Chicano Studies Department. Corona and others were fired by the college in the wake of their agitating. Blanche Taff, Corona's first wife, and the mother of his three children, died in 1993. Corona later remarried to activist Angelina Casillas. In the book, "Memories of Chicano History," which was a collaboration between Corona and historian Mario Garcia, Corona says, "Frankly, I never concerned myself with a place in history. I've been busy organizing and working with others. If my life has meant anything, I would say that it shows you can organize workers and poor people, if you work hard, are persistent, remain optimistic, and reach out to involve as many people as possible." Joining me now, to help us learn more about the life of Bert Corona is Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Kentucky, whose 2019 dissertation is entitled, "One People Without Borders: the Lost Roots of the Immigrants' Rights Movement, 1954-2006." Hello, Eladio. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 9:20

Thank you, Kelly. I love to talk about my research. I'm happy to be here.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:24

Yes. So it's super exciting to talk to you. We've known each other over Twitter for a while, so it's always good to actually get to talk to people about their research. I wanted to start by asking you, your dissertation is about immigrants' rights activists. And of course, we're going to talk about Bert Corona. How did you first get into this research? What what sort of inspired you?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 9:47

Well, I wanted to tell the story of of people that I grew up with, the story of my parents, especially, of my neighbors. Everyone that I that I grew up with, seemed to seem to be far more calm. I grew up in Delano, California, after moving to the states from Mexico in 1997. And so all I knew was this community and this community of farmworkers and poor people trying to make a living. I wanted to tell their stories. And when I started to do the research, I focused on Cesar Chavez. And what I found immediately was that there was this really unsavory story about Chavez, where in the 1970s, and even before that, you know, he was engaged in this anti-immigrant project. And I found that really bizarre because I've always thought of Cesar Chavez as this patron saint of brown people, of all brown people. And I realized that there was a larger story here, that there was a story of Mexican Americans who weren't always pro-immigrant and who actually had to come to that position, by way of this, this long struggle, you know, intellectual and labor and personal struggle. And so that's the story I ended up telling is this, this shift from from, from that moment, and really, before that. I mean, Cesar Chavez was not the first to to have these anti-immigrant positions. And that's the story, and again, I ended up telling, is how we got from from that, to today, to how we often think about Mexican Americans and their views, which are typically pro-immigrant, not always, even today. But you know, again, I wanted to sort of tell the story of of folks like my parents, and it became a bigger story about the immigrants' rights struggle, and how it how it became a movement.

Kelly Therese Pollock 11:43

Yeah, yeah. And it's a, I should mention, it's a great dissertation. I've read it. I'm one of those people that reads dissertations for fun.

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 11:51

Oh goodness. I don't, I don't think I've read my own dissertation out of pure fear and panic about all everything that's wrong with it. But I'm glad someone did.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:03

Yes. Well, it's very good. So I want to come back some to the story of the shift, but let's talk a little bit about Bert Corona, and what are the types of things that we have from him? So he, a lot of people have probably just not even heard of him at all, or maybe only in passing, but we have a lot of material about him. So what are the kinds of the records and archives that we have to know about his life?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 12:29

So the records that really tell his story are primarily at Stanford University, where the records of his the organization that that he came to be associated with that he founded CASA, the Centro de Accion Social Autonomo, or Center for Autonomous Social Justice, right, that he built from the ground up, in the 1960s. And there's also a great deal of material in this phenomenal collection that is all digitized, based in San Diego, I think the University of California, San Diego, the Herman Baca papers. Herman Baca was his mentee. He became sort of the person who took up his mantle after he, after he passed. Well before that they were working together. So there's just a an immense, a treasure trove of documents that are available online, that I use all the time to teach about immigrants' rights. And I'll always plug that because if anyone's interested in teaching, using, you know, using primary sources to teach, you can find some amazing stuff online at Herman Baca.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:38

Excellent. So Bert Corona himself, it seems like his family life is fairly foundational to sort of who he is, who he becomes. Could you talk a little bit about sort of, you know, where he's coming from, as he's entering this immigrants' rights space?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 13:57

Yeah, I mean, he was, he was always, I think, destined to become who he became. He was the son of a revolutionary during the Mexican Revolution. His father fought alongside Pancho Villa. He came from a working class family, right on the border, grew up in El Paso. Eventually they moved to, he moves to California and sees the immigrant struggle there. But for him, I mean, I think this radical tradition was instilled on him was still until very early on in his life. And he always looked for ways to improve the lives of people like his parents. I talked about how I want to tell the story of my parents, because so many of us are shaped by our upbringing in a really fundamental and foundational ways, and you can really see that in his life. I think he saw the suffering of people like his parents, like his community's suffering, and wanted in some ways, I think, to carry on that revolutionary tradition. He did it in in a different way, but I still find it odd that so few people understand how foundational he is to Mexican American identity and specifically to the immigrants' rights movement, because he is, as many of us, you know, will say, the father of the of the immigrants' rights movement.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:31

And there's you mentioned Cesar Chavez earlier. There's such an interesting connection there, then between work and labor and immigration. And so I wonder if you could talk through that a little bit, why it was that Chavez was anti- immigrant, and how sort of Bert Corona approached that differently and saw things in a different way?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 15:44

Yeah, that's a great question. And it's, it's really important to to take a nuanced approach to Chavez and his position on immigration, because it made a great deal of sense, frankly. I mean, there were immigrants, a huge number of immigrants in the Central Valley, where he was trying to make something out of this movement that that he and other farmworkers began in the late 60s. And it was making it really difficult for them to organize and to win their strikes, when employers could simply look to the border, or just to the fields where other immigrants were eager to take the work, right, and break those strikes. So it made a degree of sense for Chavez to say, you know, we can't win without, without taking this stance. Immigration was a real issue. And it was, you know, depressing wages, it was making it difficult for the Union to win its strikes. So it's not like Chavez was was just some xenophobic, you know, anti- immigrant isn't even really, I think, entirely fair. I think his positions seemed to a lot of people to be anti immigrant. He would have framed them as, as anti-scab, right, but, but Bert Corona saw things differently. And he thought that these immigrants, these undocumented people, could instead of being detrimental to the union, that they could be essential in winning these strikes, that they could be won over. And that they could be convinced to take part in this movement. And so he articulated this position over and over again, and eventually helped shift that that position. And then Chavez did ultimately shift his views on immigration, partly because of all this pressure, partly because he understood that, that it just wasn't working the way he was trying to do things, that the immigrants were going to be there regardless, and that, at some point, he was, you know, sort of fighting the same people that his union ostensibly represented. But I credit Corona with much of that shift, certainly with Chavez's own personal shift and his own views. But more importantly, with the larger shift that we see across Mexican American groups, and individuals and the entire Mexican American community, which for a time, much like Chavez, felt deeply ambivalent about immigration, if not outwardly hostile. And sometimes they were very hostile. And by the 1970s, that position has changed completely. I mean, there are still people who are anxious about immigration, there are still people today who are Mexican American, and who feel anxious about immigration. But that was a minority by the 1970s. It was a very, very quick shift. And Bert Corona is central to that shift.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:33

And Bert Corona and Chavez had actual conversation or relationship. What what did that look like?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 18:41

Well, it was always friendly. I mean, they were they were friends, they considered each other allies, friends, comrades. So it was it was always positive. And I think that's part of what shifted Chavez's attitude. So there were a lot of people, not just Corona, reaching out to Chavez and saying, "This is nonsense. This is a mistake." Some were very harsh and said, "You are betraying the movement. You this movement you're creating, you are breaking it. You're destroying your own movement, and you're hurting the people that you are supposed to be representing." There was a lot of anger and a lot of rage, and a lot of disappointment. Bert Corona was much more diplomatic in his approach and in his, in his letters to Chavez and his communication with Chavez. He always started with, "I see, I see what you're going through and I see what the movement is facing. And I know this is difficult, but let's look at this in a different way." And that really seemed to be what Chavez responded to. Now, Chavez had a dark side and by the middle of the 1970s, that that dark side was taking over. And any sort of criticism was almost counterproductive to make any change. He would become extremely defensive. And it wasn't working. Bert Corona, I think, was was really a people person who understood who he was talking to, and how he needed to be approached, and then ultimately did help shift those attitudes, in Chavez himself, and then in the larger movement.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:19

Yeah. And so one of the things that I find so interesting, and of course, I've looked at this in different groups, as I've done these series of episodes, is that you mentioned the shift in the attitude among Mexican Americans toward immigration. But it's also almost a shift in how they view themselves as a group, sort of "Who is this group that we belong to?" And then it continues, of course, right to not be just Mexican Americans, but other sort of larger Latino, Hispanic kind of group. Could you talk about that shift? Because I find it so fascinating that this isn't, you know, we look at it now and think, "Well, it's just sort of natural. Of course, it's that way," but it's anything but natural.

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 21:03

You're absolutely right. It feels natural, because we have we live in this moment where, yeah, most Hispanics, most Latinos tend to be pretty pro-immigrant, right. And again, there are exceptions. But on the whole, we tend to associate that position with with Mexican Americans and Latinos more more broadly. But yeah, that wasn't always the case. And Herman Baca, whom I mentioned earlier, and who became Corona's partner in all of this, and his mentee, likes to tell a story. I interviewed him a few times. And and others have interviewed him. And it seems like anytime anyone asks him about this, he tells the story, and he remembers Bert Corona walking into his print shop. I think it was the 1960s, early 1960s. I'm blanking on the exact date. But Bert Corona walked into Herman Baca's printshop. And they had this conversation about the Chicano movement, and what how to how to make something of it, how to protect the Chicano community, the Mexican American community. And Corona said to Baca something along the lines of "We have to get ahead of this immigration issue." And Baca tells me that his reaction was, "What the hell are you talking about? What does that what does that have to do with us?" is what he asked him. I think he says that he asked them, are you on peyote, or something like that. But he was he was genuinely shocked that that was the answer. For Baca. You know, those were two separate issues. Immigration was one issue. And, you know, the status and the challenges that Mexican Americans faced was a totally different issue. Bert Corona thought that they weren't. And I think he was proven right, that that it became the same, the same question. And very quickly, Baca came to understand that that he was right, right, that immigration control was hurting Mexican Americans as well, that they were being harassed by the authorities, especially in the borderlines, but sometimes beyond, that they were often deported. I mean, US citizens were being deported if they couldn't prove there were citizens that, that nativists were looking to hurt people who looked like immigrants, you know, brown people. And, and these, these folks faced discrimination on the job, right, because they could be seen as potentially undocumented and, and there were all these issues that no one seemed to be paying attention to, that Bert Corona said, "We must pay attention to them. We have to this is the same struggle. And and we can't really help ourselves if we don't help our undocumented brothers and sisters."

Kelly Therese Pollock 23:49

You mentioned in in your dissertation, the this idea of without borders. And so I think Bert Corona talks about that. And you say that he doesn't just mean sort of physical border between Mexico and the US. I wonder if you could expand a little bit on sort of what he means by being a people without borders?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 24:10

Yeah, I think I think it does mean a number of things. And in one sense, I think he, you know, he always dreamed of, of a world without borders. He was a radical. He was a socialist, and he reimagined, he viewed borders as inherently illogical. But he also, I think, understood the limits of that idealism. And often when he spoke about, about this ideology, "sin fronteras: without borders," I think he meant almost more of a psychological state of mind, wherein the Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants saw each other and themselves as one community. And for him, that was the goal, ultimately, for people to see themselves as brothers and sisters beyond those borders. He understood that these borders existed and, you know, his language is often idealistic; but his, his approach to the issue is often pragmatic. You know, he worked to teach immigrants their rights, to teach them basic skills like driving, like reading and writing. And so I think what that meant for him more than anything else was that that communities north and south of the border would see themselves and each other as, as fighting the same battles.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:29

You just started talking a little bit about teaching immigrants about their rights. And you mentioned CASA earlier. I wonder if you could talk some about CASA, what this organization was, why it was important?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 25:38

Sure, yeah. So CASA was founded in 1968, so Bert Corona, and Soledad Alatorre was a key partner for him. He built his organization that the name is no coincidence. CASA is home in Spanish, and he and Alatorre saw it as a kind of base for Mexican immigrants in Southern California, where they could learn about their basic rights, where they could learn about labor rights, where they could pick up basic skills. So that was the kind of the practical side of CASA. I think it was also an ideological center. It was a communication center, right, where, where people drafted statements that were well distributed, where people could come and organize and float ideas and think about ways to help Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants protect their rights and each other's rights. Out of this, this place comes the the Immigrants' Bill of Rights or the Charter of Rights, that, that Mark Day, then a Catholic priest, he has since left the church, I think the church, he certainly left the priesthood. So he's a fascinating figure himself. And he doesn't get any credit for all of this, but he's to be central to this movement. But this Charter of Rights, you know, is a manifesto. It really has no legal basis, obviously. But it essentially says, what modern activists have been saying, that there is no such thing as illegal people. Human beings cannot be illegal, that they are human beings with human rights. And, again, this doesn't have any sort of legal force, but it but it creates a profoundly important ideology. And it helps spread this idea and this message that that very quickly is picked up by Chicanos and Chicanas, people who are beaming with ethnic pride. And suddenly they understand that immigration is part of the story. And it's part of their whole struggle as well.

Kelly Therese Pollock 27:50

I think it's important and it seems like CASA is starting to get into this to understand you started this whole story with talking about farmers and how you were looking at farming. But that Bert Corona was interested, not just in Mexican Americans and immigrants on the farm and in the rural areas, but in cities and urban areas. And that seems like a really important point to make. Because I think it's still the case that people think, you know, sort of especially migrant farmworkers, you know, that that's sort of the picture they have of, of Mexican immigration. So could you talk a little bit about that about that sort of urban immigrant piece and what that meant?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 28:33

Yeah, here again, I think Bert Corona was prophetic. I think he understood that demographics, of course, were changing, but but also, migration patterns were changing greatly. So all of this this focus in the 1960s and early 70s, was on on the fields on Central California, specifically. And certainly that's that's where this farm worker movement began. And in some ways these questions really took off. But more and more people were moving to cities. And and immigrants, more and more undocumented immigrants are moving to cities, places like San Diego, of course, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Bert Corona, understood that and thought that, that there needed to be, of course a focus on the farmworker struggle. But it also has to be zoomed out and thought of as a larger movement, and things were critical. And in fact, even the people we might call migrant farmworkers are becoming less migrants and less attached to the fields. Today, for example, when I visit Delano, California or the Central Valley generally, and I talk to farm workers and they they live in the cities. They live in places like Delano and Bakersfield and Tulare. They may work in agriculture in the fields but they're not really migrant in any real sense anymore. So things were changing. And Bert Corona saw that and thought that the cities were where much of this organizing was going to be happening. And he was right. I mean today, that is where most most immigrants' rights organizing is taking place.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:14

Yeah. So I want to jump backwards in time for a minute before jumping forward in time; and the backwards in time piece is Bert Corona and World War II, I think. So he, he joins the military or tries to join the military and runs into this really quite discriminatory situation. And so I wonder if you could talk about that. And I know that you also have a military background. So I wonder, you know, if you could sort of talk about, you know, have things changed, I hope? You know, what, what did that look like for Bert Corona versus what that might look like now?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 30:53

Yeah, so Bert Corona faced discrimination in the military, like most Mexican Americans, and most people of color did in World War II and that era. I think he was disillusioned with with a lot of what he saw, he was made to feel like an outsider, which I think helped him understand the plight of the undocumented, and again, to come to this conclusion that, that like them, Mexican Americans face discrimination and racism, and class prejudices and exploitation.So I mean, certainly things have changed. I think today's military is obviously much more diverse, much more attuned to the changing demographics and values of this country. I think the worst thing that I suffered, and I tell the story, and some people find it amusing, some find it horrifying, but for a time, you know, because you can join the military if you're not a citizen, as long as you have a green card. And that was my, my situation. And all of us who were not citizens yet, we were given emails like everyone else. But we were also given a country code that had to be attached to the email. So it was like my first name.last.mx right@navy.mil, and people from the Philippines, and it's like that pi and so on. And it was this, I remember at the time feeling really just awful by that, because I mean, you know, I am serving in the US military. I'm doing what everybody else is doing. But I was literally marked with this, this foreign label. And I guess that's what you might what we might call like, a microaggression now, these days, right. I didn't have a word for it. But I knew it felt weird and odd. And I don't think they do that anymore. But, you know, certainly that's nothing compared to the kinds of kinds of things that people suffered in the 1940s, 50s, 60s, and through 70s, and around that time. But things have changed, things are changing. I mean, the military is is much more diverse. Again, I think leadership, the leadership is learning to, to work with that increasing diversity. The military these days likes to talk about diversity and inclusion, just just like universities, and others do, and just like universities and other organizations, may awfully fail to actually make something of that rhetoric. I'm sure you've seen the problems that that the academies, for example, have based on the sexual assault, assault with sexual violence generally, in the military. There, there are still instances of of racism, discrimination, but certainly, things have gotten somewhat better in in some ways.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:25

Yeah. So one of the things that that you wrote about in your dissertation that I knew, really nothing about, and despite the fact that I look at a lot of immigration history is this 1986 law, I forget exactly what it's called. But that bipartisan support signed by Reagan, that that's looking at immigration and is trying to sort of make everybody happy and makes nobody happy as it's trying to do it. So I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that, and sort of the the long term impact that that has had?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 34:13

Yeah, this story really begins in the 1960s when the bracero program ends and really picks up the 1970s when it no longer is just a story of the southwest or about the southwest workforce. Before immigration largely is confined or questions about immigration are largely confined to the southwest, but by the 70s it's a national story. And there's this nativist panic happening about the rising numbers of undocumented immigrants. Yeah, by the 80s, It's clear that that everyone wants to do something about it. But by the 1980s, we have all of these factions too, that have developed. We have a real really robust immigrants' rights movement led by people like Bert Corona and Herman Baca. We have a nativist lobby that is headed by organizations like FAIR, the Federation for American Immigration Reform. You have labor groups that don't quite know what to make of it. And you have employers who actually want more, you know, more migration and easier access. And so it's this mess that that's at least the policy, in terms of policy, it's a mess. No one seems to know what to do with it. Everyone wants to fix it, but what fixing it means, you know, means something different to everyone. And eventually we get this law that that is passed in 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act and signed by Reagan. And as I detail on the dissertation it's messy. It seems like, it's this piece of legislation seems to be dead several times. But somehow, all this bipartisan maneuvering gets it passed. And it it does essentially three things: it It provides amnesty for, initially, about a million, ultimately, about 3 million, mostly men were in the country without documents. It's it also hardens the border. So it begins to militarize it. And it creates this guest worker program. And so the idea is that you give something to everyone. The flip side of that is that it gives something to everyone. And someone's always angry about what the other groups got. What I think is important about this law is that well, first, it's it's precisely what we might call comprehensive immigration reform, which we always hear about. This really was comprehensive in the sense that it did a lot of everything, right? It, it tackled every aspect of immigration, labor, ethnicity and immigrants' rights. It just tried to do everything. And its strength was also its weakness. By doing that, it didn't satisfy any one group. And so I think what's happened since then, is that anytime we bring up this, this, this phrase, or this policy goal of, of comprehensive immigration reform, someone will always point to '86 And say, "We can't do that, because it failed. We can't do that, again. We can't give amnesty to immigrants, because then more will just keep coming and want more amnesty." The other side might say, "We can't do this, because it's just going to make the border more dangerous." So it has really kind of deadlocked us, and in this conversation, and I actually think that it was a brilliant law. I mean, there are things I hate about it as, as an activist, as someone who cares about immigrants' rights. I don't like a lot of what it did in terms of militarizing the border. But in terms of realistic policy, and what what can be accomplished? I think it was quite the achievement. And and it's it's just looking back at it, you know, I I realized how difficult it was to get that legislation passed, and also how difficult it will be to get anything passed that resembles that in the future. I think we're, you know, it was such an important law and such a such a monumental achievement. But also it kind of made everyone angry. And now, it seems like we'll never be able to do that, again, like to really sit down and look at different factions, see different aspects and come up with a comprehensive solution or solutions. I think at the time, people really saw immigration as this, this dynamic developing story. And it wasn't meant to fix immigration. This was meant to address an issue in that moment. And I think that was really what was most brilliant about it is that people looked at what was happening in the moment, and figured out a way to create, you know, fairly comprehensive legislation that that addressed every aspect of of the issue. And now people see it differently. They see it as this thing that was supposed to fix immigration problems, and didn't. It failed. So everyone thinks of it as a failure. I actually think it was a monumental success at doing at least what it intended to do in that moment.

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:15

Yeah, it's thinking from the perspective of today's politics, the idea that two parties could come together on anything is rather mind blowing.

And not just the two parties, but all the factions right, around it. And yet, it happened in 1986. And it hasn't happened since then. I don't know if it will happen again.

Yeah. I guess I just wonder if you could reflect a little bit on what, you started this project thinking about your family and wanting to study people like your parents and your neighbors. What going through doing this research sort of meant for you personally, sort of what what all of that helped you sort of think about the family and the the neighbors and all of that, and, and maybe reflect on, you know, we know that history and academia don't happen in a vacuum. But I think it's something people don't always talk about. So you know what, what it means to have that sort of personal relationship with a subject?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 40:16

I found this really healing for a number of reasons. I grew up in central Mexico in Zacatecas, and we were extremely poor. We lived in an adobe house with no indoor plumbing, for a time with no electricity. We had next to nothing, and we survived because my dad would come to the states and work here, seasonally. That also meant that he was gone, you know, six, nine months out of the year. And for for a little kid, it's, it's so hard to see your father leave every year and not know if he's coming, if he's going to come back and not knowing that he's going to be okay. When I was 11 years old, my dad came back and told us we were moving as a family and my mom and my sister to the states. And that changed everything, just because I wanted to have a more stable family and I wanted to be with my parents, both of them. So when we moved to the states, life changed drastically for me, but but I also was undocumented. And I didn't actually get get my green card until I was 19 years old, which is when I joined the navy. So putting together this, this dissertation now, now this book manuscript, has really helped me work through some of those, some of those issues of identity. I figure out where I really belong, where I come from, and where I what I've sort of made of my own identity, and I realized that it's, it's not that uncommon, right for for people like me, for immigrants, or even for first, second generation, children of immigrants, to wrestle with this question of identity about who they are. And I think you see that actually in in, you know, the subjects that I write about, they're trying to work out who they are. Are they Mexican? Are they American? Are they are they Mexican American? And if so, what does that mean? And that changes. It's never static, right? For for people in 1950s, it meant one thing. For people in the 60s and 70s, during the Chicano movement, it meant something else entirely. That is changing, again. We're we're even wrestling with with the language again, whether Latin X or Latina X works better, or if we should say Latina, or we should stick to Latino, Latina, or all these questions about identity happening all the time. And I think it's it's benefited me to be explicit about my own my own place in this story, as someone who is an immigrant, the child of farmworkers, an immigrant myself, someone who came from from Delano, California, where the the, you know, the drama of the farmworkers movement took place, I have really leaned into that. And for a time, I was really self conscious about it and thought that maybe that wouldn't be received well, but I think it matters. I think it matters that we be honest with ourselves and where we fit in the stories we tell. And I've tried to do that. I tried to do that in my own teaching. I tell my students where I come from and why these stories matter to me. And I hope it's received well out. I hope people find it to be as important as I do. And I think I think there will be some lessons in there for for activists for their stories for students. But yeah, that this is this is my story, in a sense, and it's also a story that that is relevant to millions of people. So I hope that it resonates with them. And I hope that it tells some version of the immigrant story and also the larger American story.

Kelly Therese Pollock 40:48

Yeah, I really appreciate that. I I always like when I get to see sort of who scholars are, not just their research, but who they are. And you can't help but be affected by who you are. And so I think being so open and honest about that is is really, really great. Alright, so on a lighter note, my last question for you. You're known on Twitter for your food takes and you grew up in Mexico, so I want to know what's the best Mexican food?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 44:21

Oh, that is you're really putting me on the spot. Like the best dish? Camarones a la diabla: deviled shrimp. It's something that that my mom used to make for me as comfort food, and that I have yet to perfect and I'm working on it. And one day I will, but nothing makes me as happy as camarones a la diabla, because it makes me think of my mother and and all the wonderful moments we shared together and so I always think of her and how happy it made her to make me happy with that dish. So that's always gonna be the closest to my heart.

Kelly Therese Pollock 44:58

I love that. Was there anything else you wanted to make sure we mentioned about Bert Corona?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 45:04

I don't think so. I mean, I think I mean, you know, yes and no, but I mean, I could talk about him for hours. But I think I think we got to the, the heart of who he is, and why it matters. I guess, I would just say that I find it odd that that so little is known about him. Everyone knows about Cesar Chavez, and we should. He's an important story, both because of what he accomplished, and where he failed, and his, his limits, and because he was, in a sense, a saint, and then also had his own demons, and he was a fascinating person. And maybe that's why we know so much about him. But Bert Corona, I think is just as important to the story of, of Mexican Americans on the southwest, of labor history. I think he's a critical figure that we don't pay enough attention to. And I hope to start to change that. I mean, some people have written about this recently. And, you know, I hope to really advance that story. Bert Corona is essential to our history, essential to America, essential to American history. He's certainly essential to LatinX history. And he's a huge part of 20th century labor history as well. So I hope more people learn more about him in the future.

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:23

Well, I'm so grateful to you for for sharing your information about him because I am excited to have learned about him. And if people want to follow you, so they know when your book comes out so they can read all this super fascinating history, how can they follow you?

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 46:39

I'm on Twitter, probably too much. We all are. Yeah, yeah, that's true. E_B_Bobadilla.

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:50

Excellent. I'll put a link in the show notes for that.

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 46:52

Wonderful.Thank you.

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:53

Eladio,you so much.

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla 46:55

Thank you, Kelly.

Teddy 46:57

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Dr. Eladio B. Bobadilla is an assistant professor of history and Latin American, Caribbean, and Latino Studies at the University of Kentucky.

He was born in rural Garcia de la Cadena, in the state of Zacatecas, Mexico to a poor family headed by Benjamin Bobadilla, a farm worker and musician; and Lucina Mariscal de Bobadilla, a homemaker. They lived in a small adobe house in the village of La Ceja, where Bobadilla attended a makeshift elementary school that served the small community. His father was a bracero, and later, a seasonal migrant worker, who worked in the United States for several months at a time before returning home to spend the off-season.

In 1997, he migrated to the United States to live in Central California, where his father had worked for several years in the grape fields. There, he attended Almond Tree Middle School before attending Delano High School, then the only high school in the city of the same name, made famous by the farm workers movement of Cesar Chavez and his United Farm Workers union.

Though he dreamed of going to college, his undocumented immigrant status prevented him from doing so immediately after high school. About a year after graduating DHS, however, he received permanent resident status and immediately enlisted in the United States Navy.

In November of 2005, he shipped out to the Navy’s Recruit Training Command (RTC) in Great Lakes, Illinois. There, he was promoted while still a recruit and graduated in January of 2006. Immediately following his basic training, he received advanced training (“Apprent… Read More