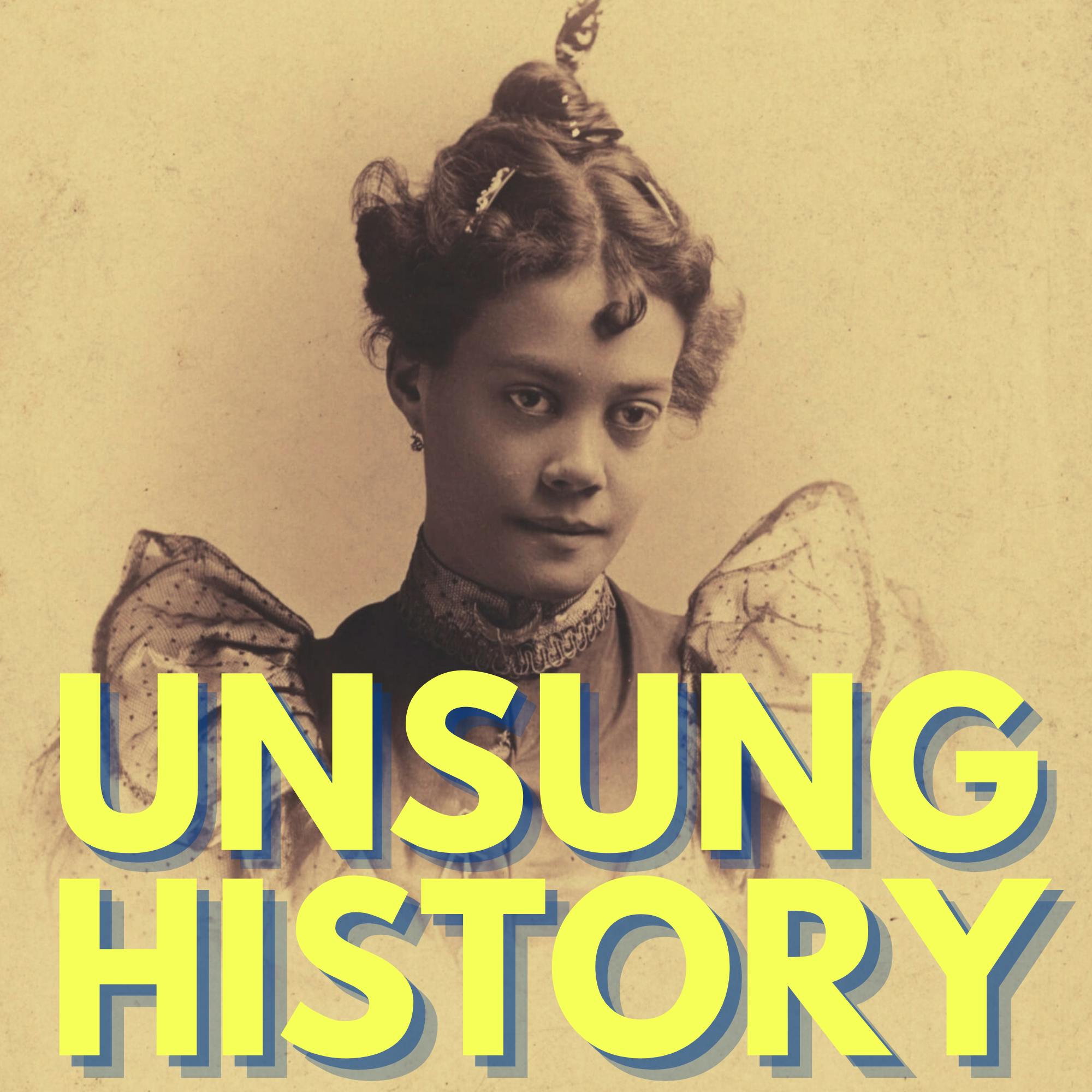

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Poet, essayist, and activist Alice Dunbar-Nelson is perhaps best known as the widow of poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, but she is a remarkable figure in her own right.

Born in New Orleans in 1875 to a mother who had only recently been freed from slavery and an unknown father, Alice graduated from Straight University (later Dillard University), became a teacher, and quickly started her own writing career. Throughout her life, Alice continued to teach and to write and to speak out on issues of women’s suffrage and civil rights for African Americans.

To learn more about Alice Dunbar-Nelson, I’m joined by Dr. Tara T. Green, Professor of African American and Women's and Gender Studies at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and author of the 2022 book, Love, Activism, and the Respectable Life of Alice Dunbar-Nelson.

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image is: “MSS 0113, Alice Dunbar-Nelson papers, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Newark, Delaware.”

Additional Sources:

- “Feminize Your Canon: Alice Dunbar-Nelson,” by Joanna Scutts, The Paris Review, September 28, 2020.

- “An Unsung Legacy: The work and activism of Alice Dunbar-Nelson,” by Grace Miller, Unbound Blog, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, March 12, 2020.

- “I am an American! The Authorship and Activism of Alice Dunbar-Nelson [Virtual Exhibit],” The Rosenbach, Free Library of Philadelphia.

- “Alice Dunbar-Nelson Reads [Virtual Exhibit],” The University of Delaware.

- Writings of Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. Today, we're discussing poet, essayist and activist Alice Dunbar-Nelson. Alice Moore was born in New Orleans on July 19, 1875. Her mother had been born into slavery, and was freed only after the Emancipation Proclamation was enforced. Although there's speculation about the identity of Alice's father, neither she nor her mother or sister ever discussed him. Alice's mother, Patricia Wright, worked as a seamstress in New Orleans, and ensured that Alice and her younger sister Lila, were educated in the public schools. Alice attended Straight University, which later merged into Dillard University, graduated from the teaching program in 1892, and quickly began working as a teacher. While teaching, Alice also began to write. Her first book, a collection of short stories called "Violets and Other Tales," was published in 1895, followed shortly after, by "The Goodness of St. Rocque, and Other Stories." Alice left the South, moving first to Boston, and then to New York City, where in 1897, she co-founded and taught at the White Rose Mission in Brooklyn, with Victoria Earl Matthews. Alice published her poetry in "The Woman's Era," which ran her photo alongside the piece. Poet and journalist Paul Laurence Dunbar was captivated by her and wrote to her a letter of introduction. They began a years-long correspondence, which turned romantic. Within six months, Dunbar declared, "I love you and have loved you since the first time I saw your picture." He called Alice "the sudden realization of an ideal." In their correspondence, Alice and Dunbar compared themselves to Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, whose romance had also begun via letters. In November of 1897, Dunbar begged Alice to come visit him, and when she did, he raped her brutally, leaving her with internal injuries. Five months later, in 1898, the two eloped despite the disapproval of Alice's mother and sister. And Alice eventually quit her teaching job and moved to Washington, DC to live with him. It was a short, unhappy marriage, and it was public knowledge that Dunbar beat her regularly. In 1902, after a particularly violent drunken beating, Alice left, moving to Wilmington, Delaware. She never returned, despite Dunbar's pleading. Alice responded to his letters only once, when she sent a one word telegram that said simply, "No." Paul Laurence Dunbar died in 1906 in Cincinnati of tuberculosis, at the age of only 33. Although they were still legally married, Alice found out only by reading a notice in the newspaper.

In Wilmington, Alice, who was then going by Alice Dunbar, taught English and Drama and directed the English Department at Howard High School. Alice developed an intimate romantic relationship with the longtime principal of Howard, Edwina Kruse, 27 years her senior, who supported Alice, both professionally and financially. In 1907, Alice took a leave of absence from Howard High School to enroll at Cornell University, where she earned a graduate degree in English. At Cornell, Alice met Henry Arthur Callis, a founding member of the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, who had entered Cornell in 1905, as one of 15 Black students. In January, 1910, after Callis moved to Wilmington, and began teaching at Howard High School, he and Alice were married. Callis was a decade younger than Alice, with plans to attend medical school, and their marriage did not last long. The date of their divorce is unknown, but eventually Callis moved to attend Rush Medical School, and he later remarried in 1914. In 1916, Alice married again, to poet and civil rights activist Robert J. Nelson, to whom she remained married until her death. Upon their marriage, Alice also became stepmother to Nelson's daughter, Elizabeth. Nelson co-founded and edited "The Wilmington Advocate", and was active in politics as a member of the NAACP and the United Negro Republican Association. Before they were married, Robert and Alice worked together on "Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence: The Best Speeches Delivered by the Negro From the Days of Slavery to the Present Time," edited by Alice while Robert was president of the Douglas Publishing Company in Pennsylvania, and published in 1914. Robert Nelson continued to support Alice's work, including not just her writing, but also her political speeches. In 1914, Alice had co- founded the Equal Suffrage Study Club, the members of which marched in a suffrage parade in Wilmington later that year. In 1915, Alice traveled throughout Pennsylvania, as part of a campaign to grant women the right to vote in the state. Alice spoke passionately, mostly to African American audiences, making the argument to African American men that the race would be stronger if African American women could vote with them. Alice also helped charter the Wilmington chapter of the NAACP, and protested against a showing of "Birth of a Nation." Unfortunately, a new principal at Howard High School, Ray Wooten, did not approve of Alice's activism, and in October, 1920, she lost her teaching job, which she had loved. In 1921, Alice and a group of activists led by James Weldon Johnson, met in the Oval Office, asking President Harding to pardon Black soldiers who had been convicted of rioting in a race riot in Houston in 1917. In the 1920s, and 30s, Alice wrote extensively, including reviews and essays, along with stories, poems, plays and novels. From 1928 to 1931, Alice was the Executive Secretary of the American Interracial Peace Committee, AIPC. The AIPC was a project of the Quaker run American Friends Service Committee, and it sought to, "develop and enlist the active support of the Negroes of America in the cause ofpeace." In 1932, Robert Nelson was appointed to the Pennsylvania Athletic Commission by Republican Governor Gifford Pinchot and Alice moved with him to Philadelphia. Unfortunately, her health began to deteriorate. And on September 18, 1935, Alice died of pneumonia, which affected her heart, at age 60. Her ashes were scattered on the Delaware River, fittingly, since she had written in her diary that she hoped to, "float on and on and on into Sweet Oblivion."

Joining me now, to help us learn more about Alice Dunbar-Nelson, is Dr. Tara T. Green, professor of African American and Women's and Gender Studies at the University of North Carolina Greensboro and author of the 2022 book, "Love, Activism and the Respectable Life of Alice Dunbar-Nelson." Before my conversation with Dr. Green, I'd like to read for you one of Alice Dunbar-Nelson's poems.

This is "I Sit and Sew" from 1918. I sit and sew-a useless task it seems, My hands grown tired, my head weighed down with dreams- The panoply of war, the martial tred of men, Grim-faced, stern-eyed, gazing beyond the ken Of lesser souls, whose eyes have not seen Death, Nor learned to hold their lives but as a breath- But - I must sit and sew. I sit and sew - my heart aches with desire - That pageant terrible, that fiercely pouring fire On wasted fields, and writhing grotesque things Once men. My soul in pity flings Appealing cries, yearning only to go There in that holocaust of hell, those fields of woe- But - I must sit and sew. The little useless seam, the idle patch; Why dream I here beneath my homely thatch, When there they lie in sodden mud and rain, Pitifully calling me, the quick ones and the slain? You need me, Christ! It is no roseate dream That beckons me - this pretty futile seam, It stifles me - God, must I sit and sew?

Dr. Green, welcome. And thank you so much for speaking with me today.

Dr. Tara T. Green 11:15

Thank you for having me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 11:17

Yeah, so I was so excited to learn about the life of Alice Dunbar-Nelson. And so I'm so thrilled that we're speaking about her today. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how you first got interested in her life and then about writing about her?

Dr. Tara T. Green 11:34

Well, I first met her in an English class at Dillard University in the 90s, when I was an English major. And that was a moment that I have not forgotten because I was not familiar with her work. I had grown up in the suburbs of New Orleans, and so had not been introduced to her work prior to being in that classroom. And then I was fascinated to learn that she had graduated from Straight University, which was an earlier iteration of merger with New Orleans University to become Dillard University. And so that moment of revelation for me, and her description of a New Orleans that I was familiar with, because I was sitting in the city of New Orleans was a new introduction of New Orleans for me, and it was, it just resonated with me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:33

Yeah, so she has this just absolutely fascinating life. And, you know, I think a lot of the people that are maybe that I feature on here that are sort of unsung, and you know, maybe people don't know as much about, you know, often we maybe lack some sources. But there is just an incredible wealth of sources here of her own writing, especially. So I wonder if you could talk some about kind of the wealth of sources that you were able to look at to write about her, and then the sort of the way that you analyze those kinds of sources?

Dr. Tara T. Green 13:10

Well, there is so much she kept from about 1895, around the time where she begins to correspond with Paul Laurence Dunbar, her first of three husbands. She begins to, she, first of all, she keeps that correspondence. And then she keeps gosh, I mean, everything. I imagine that she had to have thrown some things away. But what she actually kept, is mostly in boxes at the University of Delaware. So once I learned that there was some documents there, I had no idea really how much. And I went there. And I thought, "Wow, nobody's written a biography about her." And I knew that I was going to have to do that. So I would go back to the University of Delaware several times. And she was also an editorial writer, and she did not really keep, whatever newspapers she may have had had probably just sort of disintegrated. So those are not, there aren't very many copies of her actual writing, editorial writing in those boxes. But thankfully, we have databases of Black newspapers from her time. And so I was able to look at her work through those databases. So the technology along with the historical records really helped me to be able to pull together this book.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:46

One thing that's interesting, of course, is with all of these sources, there are still some gaps and some silences, you know, years where either maybe she didn't keep a diary or or it was destroyed, or she burned it or something, you know, and there'll be times when there isn't correspondence back and forth, because she's living with whomever she would have been corresponding with. So can you talk some about the effect of those those gaps, those silences? You know, if there are things that, you know that maybe we can't quite get at? Or if there's anything to be learned from the fact that there are silences in some places?

Dr. Tara T. Green 15:25

Yeah, well, sometimes the silences, we just have to deal with the fact that the material isn't there. I am, or I was able to kind of compensate a little bit based on having letters. So for example, letters that she had from several people, it was clear that that person may have been responding to something that she said. So we could do inferences from that, which is what I did. Sometimes the difficulty of someone referring to some folks that I could not find the name, again, in the archive or connected with that person. And, and so the kind of intimacy of those conversations would pull me in a different kind of direction, so that I couldn't get close to who was saying what or why, but how it may have made her feel. So I would tap into the the apathy, the emotion of the experience, because it was probably something else going on in her life at that same time. So and that's what happens, right? We have friendships with one person, but we may also be taking care of a parent, and we're teaching and so on. So so I was trying to pull apart specific incidents, but also to try to capture the layers of a particular moment also.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:06

So when you're looking at the life of someone like this, who has both private writing, so private at different levels: journal is presumably just for herself, correspondence is theoretically, just for that one other person. But then also lots of public writings, both fiction and journalism, as you mentioned, you know, what, what do you see in the way her voice maybe differs in those different kinds of contexts, or, you know, you talk a lot about respectability. And so how that sort of plays out as she's writing in these different contexts?

Dr. Tara T. Green 17:42

Well, she definitely knew how to keep these voices separate. And so that's what I loved about the diaries, because we got a sense of who she was from the diaries and what she was suffering through, and what she really wanted, how she really felt, for example, about art. So if she would go to a drama or a film and see a particular artist, she may have some negative comments from that artist in her diary; but when she wrote about that, that, that drama or that film in her editorials, she would be quite kind. And so it was always the public face of the Black experience that she made primary in her work. And secondary may have been how she personally felt about a particular situation or a person or any event.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:49

So let's talk some then about this respectability and so that you know you have that right in the in the title of your book about the respectable life. And you come back to it several times in the course of thinking about her life and, and the way as we're talking about the that she presented herself and so can you talk some about what maybe both what you mean by respectable and respectability and what that meant to her?

Dr. Tara T. Green 19:18

Yeah, so I am playing off the the ideal of the politics of respectability, looking at the work of Evelyn Higginbotham. So, what did respectability mean to those women of that time, particularly in this late Victorian Age for Black women who wanted to present themselves in such a way that that presentation itself was an act of resistance to how they may have been thought of as not being ladies, as not being educated, as not being worthy of equal treatment in society. And so the public didn't always line up, however, with the private. And so, first of all, she was married three times. Well, women didn't do that. So she left her first husband. And she becomes his respectable widow. People knew that Black folks knew that she had left him. But she also separates from a second husband. But she dies with a third husband. Along the way, she has affairs with men and women. And that's part of the private life. So how she defined respectability is something that I hope will expand our thinking around Black women of this time, what they had to do, and what they chose to do, to tap into pleasures of the life is what I try to capture in the biography.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:03

So let's talk some about that first marriage with Paul Laurence Dunbar. And as you just mentioned, she leaves him but later is known even after she's married, two more times known as as his widow. Can you talk some about that relationship and how formative that relationship was for the rest of her life and for, you know, sort of both what, what respectability in a way that gave her being sort of his his widow and carrying on his legacy, but also in sort of learning about herself and what she would and wouldn't put up with?

Dr. Tara T. Green 21:41

Well, she came from a woman centered family, her mother was the matriarch of the family, and she had a sister and her sister ended up no longer being in relationship with her husband. And so Alice becomes a co-parent of her sister's children as well. Alice doesn't have her own children. So the relationship that she has with Dunbar begins through writing. Their, the night that they meet is the night that they become engaged. But throughout that writing that correspondence, we can see the abuse. We learn of the abuse that she deals with prior to the marriage, which eventually, in some ways, becomes the reason for the marriage and that she endures during the marriage. So when she leaves, her sister and her mother are already living with them. And I think that, you know, we can only surmise because she doesn't really talk about that, she kind of deals with it a little bit in her short fiction, but or even in her longer fiction, actually. But it's a moment clearly where she says, "Enough is enough." And what she says is, it wasn't the physical abuse. But it's the slander. And that is an attack on the respectable life that she is trying to lead. So you know, it's a very complicated situation. But she is very smart, in keeping his name, of course, because he was well respected, regardless of the kind of person that he was. And he was a troubled, complicated, talented individual. There have been biographies written about him. And I know that there are biographies that are being written about him right now. So what I tried to offer in this book is her perspective on what it means to live with a man who is well known and well respected, because he is well known, but she has a different kind of experience with him. So keeping his name allows her to continue to sit at certain tables, and polite society amongst middle class Black people, but she also has to carry with her the history of what it is to have been his wife.

Kelly Therese Pollock 24:24

And it's interesting that she keeps his name even after certainly in her second marriage, which didn't last very long. But even in her third marriage, which was longer and you know, seems to have been a better relationship and you know, then she hyphenated and becomes Dunbar-Nelson. What was your sense of of, of her relationship with her third husband and about, you know, what reaction he might have had to her sort of keeping the Dunbar name and the Dunbar legacy, still sometimes being called you know, Dunbar's widow you know, what, what that might have meant for their relationship?

Dr. Tara T. Green 25:01

He had no problem with the fact that she had his last name because he also got some benefit out of that, as well. She was getting royalties from Dunbar's work. And, again, she was well respected within the community of Black people during that time. He's very clear that he doesn't, he did not have a problem with it. The relationship she had with him was one of, it was certainly I think the better of the three relationships in the sense that she worked with him on various projects, political projects, as well as literary projects. He doesn't seem to, he's very supportive; he doesn't seem to be one that tries to keep her from doing certain things. So they are partners, they're kind of partners in crime. They try to come up with ways to keep each other elevated within society; and that eventually works, for the position that he gets a political appointment that he gets a couple of years before she passes away. But they certainly do have their struggles financially because he is not able to bring in steady funding. Her funding comes in from royalties, but also from teaching, which she loses her job at a certain point. And so it's the it's a relationship that works very well for her.

Kelly Therese Pollock 26:38

I wanted to ask too, about sort of switching gears a little bit about the club women. So and this is something you talk about, especially in certain parts of her life, the the clubs become sort of really important. So can you talk some about that, that kind of what these clubs are and the the role they play for Black women and and how that sort of ties in with this idea of the respectable life and respectability?

Dr. Tara T. Green 27:11

Yeah, well, the clubs that Black women had, white women had clubs as well. But Black women were not invited into those clubs and Black women had specific kinds of things that they were interested in, because it was always about how do we use this opportunity to work with one another to strengthen the race. So they would begin to meet and position themselves while slavery was still taking place. And then they would become nationally organized in 1895. So what, she was involved with the National Association of Colored Women's Club, but she started off in the Phillis Wheatley Club in New Orleans. Probably certainly we know that the president of that organization was her teacher. But, and she was a teacher. So it's so several of the women we know for sure, were teachers. And that's important because of what they see and what they feel like they want to do for the youth. And New Orleans, which is in the south, which is dealing with segregation, or lack of resources. So what these women are able to do in terms of pooling resources with the meager salaries that they get from their teaching, you have to remember that Black women were not paid the same as their white counterparts. And certainly, women weren't paid very much. I mean, these are things that we are still talking about and dealing with in society today. They were dealing with them then at a very great, on a greater scale. So the club women were concerned about what may have been going on in Africa. They had newsletters, where they let people know what was going on and what they were doing. And the kind of philosophy that they had that did tap into respectable living and morals. Christianity was certainly important. And so it was all about improving the condition of the youth, strengthening families, and that would strengthen the communities and help them to be better positioned in their fight for equality.

Kelly Therese Pollock 29:41

And toward the end of her or I suppose later in her life, then, she becomes an honorary member of a sorority too. Did the sororities play a similar kind of role?

Dr. Tara T. Green 29:53

They did. Delta Sigma Theta sorority, of which I am a member. The club women were the sort of, if you will, kind of mother organizations to these sororities that started in the 1900s. And so she was already doing much of the work that the sororities would do. But the sororities were focused on college women, college educated women, which of course, she was college educated as well. So it was a nice fit for her. And it was logical. Delta Sigma Theta 's first public event was to participate in the Suffrage March of 1913. And she had already been involved in suffrage work. And so you know, if you look at that picture of those 22 women that are the founders of the organization, they, you know, it's, it's, you can see them with their long dresses on and, and we know that, that they were to be the gems of society once they graduated from Howard University, and then other chapters would develop. So she was well positioned to attend conferences and to give talks and to, to connect with that organization.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:17

Yeah, so you just mentioned the suffrage work. And you know, when, when you see lists of suffragists, you don't often see her name. But she had such a profound effect on the suffrage movement. And it sounds like especially her ability to give speeches, to stand up in front of a crowd and to really sort of persuade them. So can you talk a little bit about that piece of it, and why we maybe don't hear her name as much in reference to the suffrage movement?

Dr. Tara T. Green 31:51

You know, it's kind of odd that we don't hear her name. She was for years, really up until her death, but even in the late 19th century, was involved with fighting for political rights for women. And it wasn't just Black women that she was concerned with, because fighting for women's right to vote meant for her that women should have the right to vote. And so she was a speaker trying to get the state of Pennsylvania to pass an amendment for women. Well, it died. But she did quite a bit of speaking, she was on the speaking circuit for that. She wrote about political rights. And all of this was very important to her because it wasn't just the suffrage movement. Even after the suffrage movement, she would continue to work with women locally and nationally, to get the people that they helped to get into office to stay on task. If we voted for you for this purpose, then we demand that you do what you said that you were going to do. And so she did not seem to tire from doing that work. She was very much so a political activist.

Kelly Therese Pollock 33:23

Yeah, it's funny. When you say she didn't tire from that work, it seems like she didn't tire from anything. She just seems relentless. I think at one point in the book you talk about in some place that she's like always searching for something and it feels like it I guess I kept sort of wondering what what is driving this, you know, the that she is doing a million different things, and has lots of relationships? She's caring for her mother and her sister's children. And do you have a sense of from from her writing, of what was sort of driving the sort of relentless, always active, always doing something, working, striving?

Dr. Tara T. Green 34:09

Well, she also struggled with having a skin color that people may perceive as white, which worked for her, in some instances when she actually does pass for white, for example, to get better accommodations on a train. But it also worked against her. She felt as though there were Black people who thought that she thought that she wasn't really Black. And so I think that the work that she did, to advance the race actually gave her purpose and identity because she knew she wasn't white. She couldn't be accepted as white. And she she swore an allegiance, to being Black, because her mother was a formerly enslaved woman. So that was very important to her. It gave her a kind of identity for one. Two, I think that she loved giving speeches. I mean that there's no doubt in my mind, the fact that she really loved giving speeches. Her feelings would get hurt if if, if her husband, Robert Nelson did not feel as though she said what he may have wanted her to say or something like that. So she took pride in doing that work. So I think that she liked being in the spotlight. She had been giving speeches since she was quite young. I was able to find that in the Newspaper Archive. And so this was work that she got a level of gratification from, and pleasure. But also, I do believe that she believed in the work that she was doing, that she honestly wanted to help people. So all of that was important to her, that's you talk asked earlier about kind of who she was as Alice Dunbar-Nelson. And that's, I think, at the heart of who she was.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:18

So we talked some about her marriages. But as you mentioned earlier, she also had affairs, both with men, and very significantly with women, some some, especially one very meaningful, long standing affair with a woman. So can you talk a little bit about that piece of it? And, you know, she never sort of had public relationships with women and what you know, obviously, we can sort of understand that given the the time, but you know, what, but you know, what, what these relationships meant to her life, and in you know, what, what we see in in her writing, about, you know, especially with Edwina Kruse?

Dr. Tara T. Green 37:03

The relationship that she had with her was long and complex. It was complex, of course, because this was the woman who was the principal where she worked. And she, they lived in Black Wilmington. And I call it Black Wilmington because it was segregated. So it's not as if they could have existed in a city even after the relationship was over, and not have crossed paths or, or would not have been associated with one another, or, or that kind of thing. And so it's important to sort of understand that community was a close-knit community for those people who were educated and connected to that particular school, Howard, which was the heart of the community. So that relationship, like I said, was complicated. So people will have to read to get the nuances of that. But yeah, she had relationships, shorter relationships with women. What we also get a sense of in reading her diaries is that she also, what Gloria Hull, Gloria Akasha Hull calls it is a kind of lesbian network within the Black club women network. And so more research needs to be done on that. Because what is going on when people are getting on trains and meeting at these conferences? Yes, they are having meetings, but what else is going on as well? What are what are some of those relationships? And that becomes important, you know, we can say, "Oh, well, we're just kind of being nosy." But you know, those kinds of relationships, understanding who's connected to whom and why also helps us to understand how how agendas are made, and how decisions are made in these meetings. So I didn't get into the weeds of that. I was just interested in who she was with and what she was doing, because it becomes important to understanding who she was. And to understand that that means that her relationship with her at least certainly her third husband was complicated also. He did know. He accepted, I think who she was and so it really says something important about that relationship that people are stunned. I've had this discussion with people that they just can't believe that this was going on behind closed doors at this particular period because they tend to think about these women, particularly Black women, as just being sort of straight-laced and this is how they live their lives and and so on. Yeah, people have private lives. This could be part of the privacy, it certainly was for her.

Kelly Therese Pollock 40:06

Yeah. And she she just seems to have been so passionate in general, you know, in a way that that piece of it doesn't seem surprising, maybe surprising for the time. But you know, it doesn't seem surprising the that she would have had sort of so much passion and so much love that, you know, it encompassed a lot of people.

Dr. Tara T. Green 40:25

Yeah, she was a passionate woman. She really was.

Kelly Therese Pollock 40:28

Yeah. You mentioned that people will need to read to understand more of the relationship with Edwina Kruse. And I think that everyone should read this book. So can you tell people how they can get the book?

Dr. Tara T. Green 40:40

Well, certainly. You can go to the Bloomsbury websites. You can go to my website, and I have links, and my website is www.DrTaraTGreen.com. So that's Dr. Tara T. Green.com. And there are links there that will help you to get to where you need to be, but it's very easy to get.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:07

And you have another book coming out too.

Dr. Tara T. Green 41:10

Yes, "See Me Naked" "See Me Naked: Black Women Defining Pleasure in the Interwar Era," and that should be available. So people are getting it, the link to it through Kindle books. But the printed version will be available on February the 11th from what I understand, and that has been published by Rutgers University Press.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:36

So you're pretty busy.

Dr. Tara T. Green 41:39

I am but those two books are in conversation. In fact, I started with a quote from Alice Dunbar-Nelson. So they are in conversation. They both deal with respectability politics and how Black women respond to and navigate those politics.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:57

Excellent. I look forward to reading that one as well. So is there anything else that you wanted to make sure we talked about today? I know that there's a whole bunch of her life that we didn't even quite get to. But you know, is there anything that that you definitely want to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Tara T. Green 42:12

Well, I hope that people will remember that she led this fabulous life. But what brings me to her and many people to her is that she was a fiction writer, I think that she had a kind of mastery over short fiction. People would think about her, someone described her once to me as a minor writer of of local color. And I've never thought of her as a minor writer. I've thought of her as a woman who had an ability to observe what was going on around her, and to use the kind of silence and sight, silence and sight to talk about the condition of women at a particular time. And what she saw of those women then are some of the questions that we still ask today of women and about women's condition in society. So I would certainly encourage people to look up her work. You can find it free, that some of her work free in the public domain just by clicking around on the internet.

Kelly Therese Pollock 43:25

Excellent. And I will make sure that in the show notes, I put links, both to your website, but also to places where people can find her work.

Dr. Tara T. Green 43:35

Great. Thank you.

Kelly Therese Pollock 43:36

Well, Dr. Greene, thank you so much for speaking with me. It's been a pleasure to talk to you about Alice Dunbar-Nelson, and I'm so thrilled that I got the chance to learn more about her and her life.

Dr. Tara T. Green 43:49

Thank you so much for reaching out, I appreciate it.

Teddy 43:54

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @unsung__history, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistory podcast.com If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Tara T. Green is Professor of AADS and the Linda Arnold Carlisle Excellence Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies. She received her bachelor’s degree in English from Dillard University in New Orleans and her Master’s and doctorate in English, with an emphasis in African American literature from Louisiana State University. She served as director of AADS from 2008 to 2016. Before coming to UNCG, she taught at universities in Louisiana and Arizona.

Her research interests include African American autobiographies, twentieth century novels, gender studies, Black southern studies, African literature, and the U.S. Black diaspora. She has published numerous articles and made presentations in these areas of research. Her books From the Plantation to the Prison: African American Confinement Literature (Mercer UP, 2008), A Fatherless Child: Autobiographical Perspectives of African American Men (U of Missouri P, 2009; winner of 2011 National Council for Black Studies for Outstanding Publication in Africana Studies), Presenting Oprah Winfrey, Her Films, and African American Literature (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), and Reimagining the Middle Passage: Black Resistance in Literature, Television, and Song (Ohio UP, 2018), reflect her interests in African American literary and interdisciplinary studies. Inspired by her fondness for New Orleans, she is completing a manuscript on Alice Dunbar-Nelson, a writer and activist from New Orleans. In addition to presenting locally and nationally, she has presented her research in England, the Caribbean, and Africa.

Dr. Green is the … Read More