Alaska Territorial Guard in World War II

Prior to World War II, most of the US military deemed the territory of Alaska as militarily unimportant, to the point where the Alaska National Guard units were stationed instead in Washington state in August of 1941. That changed when the Japanese invaded and occupied two Alaskan islands in June of 1942.

The US government responded first by evacuating Unangax̂ villagers and forcibly interning them in Southeast Alaska in facilities without plumbing or electricity for two years where many died of disease.

To protect the Alaskan territory from further invasion, Major Marvin R. “Muktuk” conceived of a plan to defend the Alaskan coast with local citizens. The more than 6,300 members of the Alaska Territorial Guard (ATG) were as young as 12 and as old as 80 and represented 107 Alaskan communities and many different ethnic groups, including Unangax̂ , Inupiaq, Tlingit, and, Yup'ik, among others.

Without the ATG serving as the eyes and ears of the US military in Alaska, the Japanese may well have invaded the mainland of the territory, setting up an ideal location from which to invade the United States.

To help us learn more about the Alaska Territorial Guard I’m joined by Dr. Holly Guise, who is Iñupiaq and an Assistant Professor of History at the University of New Mexico. Her research focuses on gender, Unangax̂ (Aleut) relocation and internment camps, Native activism/resistance, and Indigenous military service during the war.

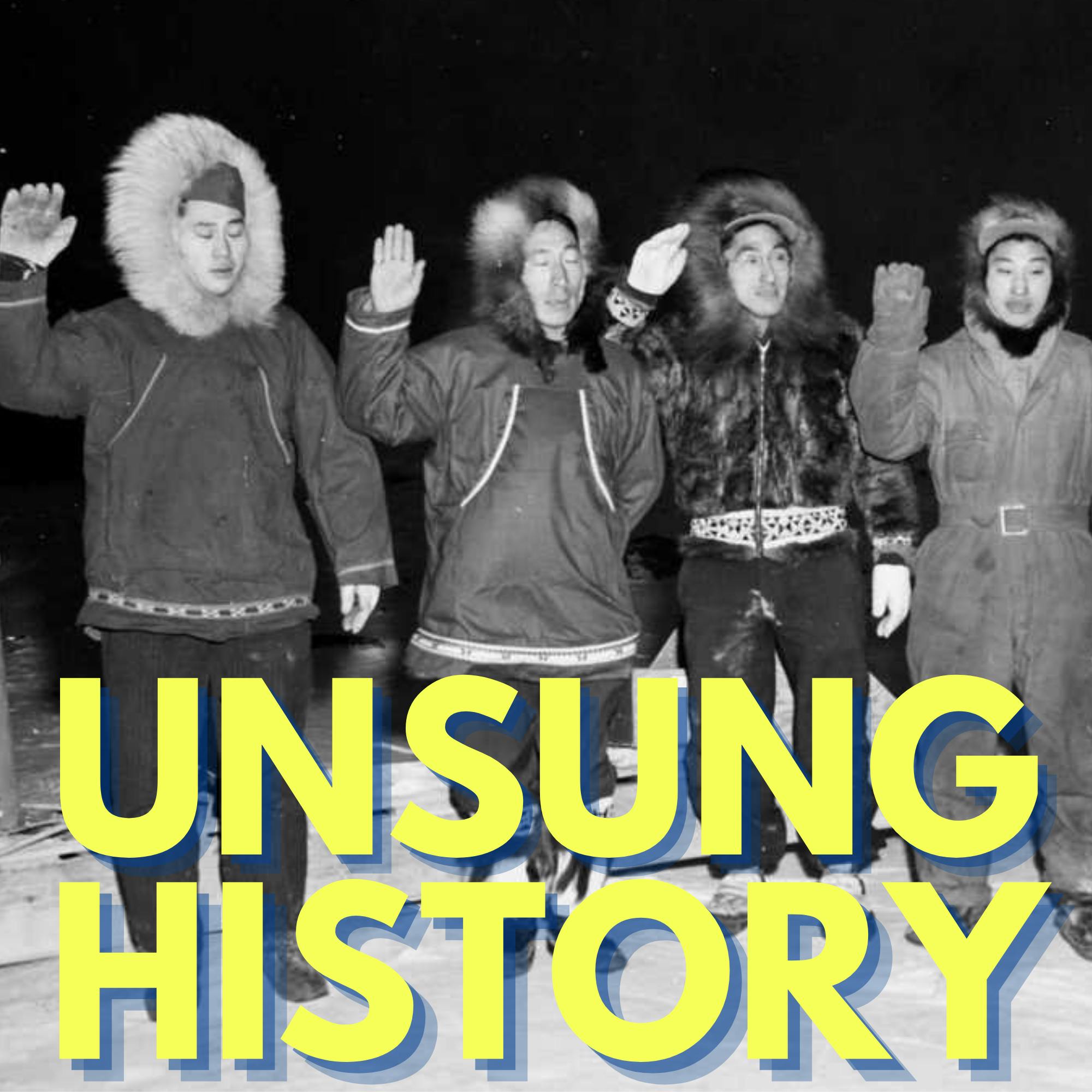

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image shows four Alaska Territorial Guardsmen being sworn in for an assignment in Barrow, Alaska, from the Ernest H. Gruening Papers, Alaska & Polar Regions Collections, Archives, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

We ask that you consider supporting the efforts of Atuxforever, a nonprofit with the goal of raising funds for Attuans to travel back to their home island of Attu for pilgrimages and cultural revitalization.

Sources and Links:

- World War II Alaska

- “Sens. Murkowski and Begich Gain Victory for Alaska Territorial Guard,” July 23, 2009

- “Under threat of invasion 75 years ago, Alaskan natives joined the Army to defend homeland,” by Sean Kimmons, Army News Service, November 16, 2017.

- “Searching Alaska for the Alaska Territorial Guard,” State of Alaska Website

- “Alaska Territorial Guard,” National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian

- Alaska’s Digital Archive

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. Today's story is about the Alaska Territorial Guard or ATG. In the 1940s, Alaska was not yet a state, but a territory of the United States. As World War II loomed, aside from Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr, the US military decided that Alaska was not important militarily. In 1937, US Army Chief of Staff General Malin Craig said, "The mainland of Alaska is so remote from the strategic areas of the Pacific that it is difficult to conceive of circumstances in which air operations therefrom would contribute materially to the national defense." With that thinking, Alaska National Guard units were moved to Washington State in August, 1941. By early 1942, a Japanese Navy reconnaissance unit was surveying the Alaska coastline. Submarines and aircraft were spotted, and in June, 1942, the Japanese Navy bombed the Dutch Harbor Naval Operating Base and Fort Mears on Amaknak Island in Alaska. In the only invasion of the United States during World War II, the Japanese invaded and occupied two Aleutian Islands, Attu and Kiska. The US government evacuated 881 Unanga from nine villages in response to this aggression and set their homes on fire so they would not fall into Japanese hands. Unanga were forcibly interned in southeast Alaska, in facilities without plumbing or electricity for two years, where many died of disease. The Japanese invasion of Alaskan islands was enough to finally convince the military of the strategic importance of Alaska. Major Marvin R. Marston, also known as Muktuk Marston had already conceived of a plan to defend the Alaskan coast with local citizens and Alaska territorial Governor Ernest Gruening approved. Alaska command assigned Major Marston and Captain Carl Schreibner as military aides to Governor Gruening, who would serve as commander in chief, and they started forming citizen units. From the formal inception of the Alaska Territorial Guard in June, 1942 until it was disbanded in March, 1947, more than 6300 members joined according to the official roster, but many more Alaskan civilians helped the ATG by providing equipment, supplies and food. Except for the 21 staff officers in full time paid positions, everyone else in the Alaska Territorial Guard was an unpaid volunteer. The group included at least 27 women, many of whom served as nurses in the field hospital at Kotzebue. One of the women, Laura Beltz Wright of Haycock was known as the sharpshooter in her company, scoring 98% bull's eyes. The Alaska Territorial Guard members were as young as 12 and as old as 80 and represented 107 Alaskan communities and many different ethnic groups, including Unanga, Inupiaq, Tlingit, and Yupik, among others. With the mission of defending the 6640 mile Alaskan coast, the ATG trained for enemy combat, patrolled and shot down Japanese air balloons carrying bombs and radios, constructed buildings and air strips, transported equipment and supplies,distributed food and ammunition and broke trails through the Alaskan wilderness. The Alaskan Natives were well prepared for this kind of work with intimate knowledge of the Alaskan terrain and weather and experience hunting with rifles. Without the ATG serving as the eyes and ears of the US military in Alaska, the Japanese may well have invaded the mainland of the territory, setting up an ideal location from which to invade the United States. Despite their importance, the contribution of the ATG was largely ignored by the US military after the ATG disbanded in 1947. In 2000, Alaska senior Senator Ted Stevens, who himself was a World War II veteran, sponsored a bill to recognize the ATG. The legislation was signed into law and ordered the Secretary of Defense to issue honorable discharges to Americans who served in the ATG. Alaska's Department of Military and Veteran Affairs set up a task force to notify former members and their families of the benefits due to them. In a 2009 press release, praising the passage of legislation to restore retirement benefits for ATG members, Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski wrote, "The Alaska Territorial Guard was our primary defense against further incursions into our great land. The members of the Alaska Territorial Guard agreed to put their lives on the line to defend Alaska. The sacrifice and commitment to the defense of America was no less significant than that of our active duty forces." Joining me to help us learn more about the Alaska Territorial Guard is Dr. Holly Guise, who is Inupiaq and an Assistant Professor of History at the University of New Mexico. Her research focuses on gender, Unangan relocation, and internment camps, Native activism and resistance, and indigenous military service during the war. In the show notes, I'll put a link to a nonprofit that raises funds for Attuans to travel back to their home island of Attu for pilgrimages and cultural revitalization. If you're able, I hope that you'll donate. Hi, Holly. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Holly Guise 7:40

Hi, thank you for having me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 7:42

Yeah. So we're going to talk about the Alaska Territorial Guard, and I have to say before I looked at your World War II Alaska site, I had no idea that this existed, so super exciting for me to learn about. So I wanted to start with just asking, you know, how you got into this topic as something to research and you know, look more closely at.

Holly Guise 8:05

Yeah, so the interesting thing is, I had heard some stories about the Alaska Territorial Guard growing up. I was born and raised in Anchorage, Alaska, and my family is from Unalakleet which is an Inupiaq village in like Northwestern Alaska. So my grandpa Lowell Anagick, was in the Alaska Territorial Guard. And so he had told some stories about that when I was growing up, and at some point, he even mentioned someone named Muktuk Marston. And I remember asking him, "Who's Muktuk Marston?" And his answer is kind of funny, because he said, "You better get to know who Muktuk Marston is." Like, I'm trying to. Yeah, he didn't really tell me but it was more like figure it out yourself kind of, you know, look into it. And then it was probably at least like a decade later, or something that I actually started kind of delving into this World War II Alaska history. And there was Muktuk Marston like, pretty prevalent, like within the Inupiaq and Yupik community with the Alaska Territorial Guard formation.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:04

Yeah, that's so neat. So one of the things I'm always curious about, and certainly in this instance, is, is the sources for research and sort of how you do research. You know, I imagine a lot of times when you're doing military research, that there's big military archives, but that might not have been the case here. You know, and so how you get at, at this history at these kind of stories that that you want to tell?

Holly Guise 9:29

Yeah, I think a lot of that goes back to my training from undergrad. So I know that makes me sound kind of hopefully not too junior varsity. But, you know, back when I was an undergrad, I read an article about Alaskan segregation during the 1940s, and it was written by Terrence Cole. And after I read the piece, I thought, well, this is really great, but what do Native people have to say about feeling segregated and being segregated before the passage of the 1945 Alaska Equal Rights Act? So I received some great mentorship from Professor Matt Smith in the Native American Studies Department at Stanford when I was an undergrad, and he helped me get funding through the Community Service Research Internship through the Center for Comparative Studies in Race Ethnicity. And with that funding, I received mentorship from the Alaska Native Policy Center, also the First Alaskans Institute. So I received this mentorship from community based organizations and Native organizations in Alaska, alongside academic mentorship from my advisor. And that's really how the oral history project took off. So this community mentorship really helped me kind of get to know people within the community. At this time, I was kind of like a co-intern through the First Alaskans Institute. And there were probably like 30 other, you know, young adult, college aged Native students, and people were saying, "Well, you should interview my grandma, you should talk to this person, you should go to this town." And so with the research funds, I was able to kind of travel to different places around Alaska, and connect with people. And I really think that the interviews were successful because of the snowball method. So basically, meeting someone from through their grandparents or something, and then after the interviewer asking, "Do you know someone else in town I should talk to?" And then I would call up the other person and say, "Hey, I just talked to so and so. Can I talk to you later today or tomorrow?" So the project kind of like, the project kind of took on like very naturally, and, and I really can't stress enough how important like the community mentorship was, with the oral history project taking off.

Kelly Therese Pollock 11:38

What does that process of oral history interviews look like? How do you get at the experiences? How do you get at sort of putting a narrative together? When you're talking to people how do you know what, what to ask them who you know what to talk about, and then sort of put all of these sort of disparate sources, sources being people together?

Holly Guise 12:00

Yeah, that's a really great question like, how do you know what questions to ask? And how do you find information like solely through the oral histories or while also with the archives? And it's definitely a combination of both. The one thing I'll say about the archives is archives tend to lack direct Native perspective. So a lot of the archives that have information about Native people aren't usually written by Native people. Or if it's a photograph of Native people, sometimes it doesn't even say the names of a Native person, you know. So I think for that reason, the oral history is really important. And the other thing I would say about the oral histories is it really fits within kind of traditional ways of acquiring knowledge within the Native community. So like the way you would learn information, like I'm speaking generally here, but the way you would kind of learn information, if you're Alaskan Native is kind of learning from the elders. Right. And so this is also an interesting way that the oral histories kind of fit this indigenous framework too.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:05

Yeah, that's really neat. So as you have talked to people, and we can talk some about your your other research as well, but specifically about the Alaska Territorial Guards, you know, what, what were the motivations people had for joining up with, you know, this service that that they didn't even get paid for? So the overwhelming majority of them are volunteers, and there's sort of this huge age range of who's participating. So what why did they get involved? Why Why was this something that they wanted to do?

Holly Guise 13:37

Yeah, they had a number of reasons for being involved. I think the primary reason was fear of imminent attack by Japan. So in June of 1942, Japan invaded the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska, took Attuan prisoners of war to Hokkaido, the north island of Japan, and also bombed Dutch Harbor, which was where a US base was, and basically, basically, Native people chose to ally with the US to defend the coastline from further invasion. And, while this seems kind of like long ago, and while it also seems kind of on the peripheries of empire, Alaska had a lot of strategic value, in terms of kind of being this place that's like a borderlands straddled between the empires of US, Canada, Russia and Japan. And Alaska itself, the landscape had also been kind of contested by these several empires for, you know, several kind of decades and generations, right? There's even like accounts of like Japanese fishermen, poaching waters and other things like that, like before the war. So basically, it's kind of it's kind of no surprise that there's tension at the borderlands, right? But I do think that when Native people saw the opportunity to ally with the US military and to utilize resources, for example, World War I era Enfield rifles, they seized on that opportunity. And it's actually very similar to other regions of the Pacific. So I was reading a book just the other day by Stacey Salinas, called "Pinay Guerrilleras." And it's actually about Filipino women who formed guerrilla platoons during World War II to kind of guard the Philippines. So there's other parts of the Pacific, where we have kind of Native nations or other nations selecting to ally with US Empire at this time, instead of Japan.

Kelly Therese Pollock 15:44

Yeah, that wow, that is fascinating. And what were the kinds of things you know, if if what they're doing is trying to ally with the US to, to protect their homeland, but also to make sure that Japan doesn't get this valuable resource, you know, what, what were the kinds of things what were the kinds of ways that that the territorial guard was was able to do that, you know, what, what were the kinds of methods what kinds of training did they have?

Holly Guise 16:10

Yeah, you know, it's interesting because a lot of the training included drills. So Major Marvin Marston, who acquired the nickname Muktuk Marston because he could eat as he could eat as much muktuk as the Inupiaq people. Muktuk is whale blubber, so it was kind of a an endearing kind of nickname for him. And so, Muktuk Marston kind of worked with the native tribes like on practicing these drills, distributing World War I era Enfield rifles, and in some cases, even giving old uniforms or like ATG badges. So some of the villages had kind of a uniform or certain clothing. But then most of them had an ATG badge that they would put on their parka. And so they practiced drills, they checked for enemy planes, and they reported enemy planes. And at this time, there were Japanese planes that would fly overhead, that would fly over Alaska. And so they would report these, they would also identify the model of planes. So that way, the US military would know what models were flying over Alaska. And they would even do things to kind of protect their community, like by storing food in food caches, and distributing food to those in need. So there were also a lot of social services that the ATG provided, in addition to having social activities like dances, and these dances would include, you know, traditional Native dances, right? So yes, there would be jitter bugging but there would also be kind of traditional drums and traditional Native dances as well. So it was really a community organization. And, while photographs tend to show Native men and even young and older Native men participating, there were a fair number of Native women who were also involved in the ATG, and some of them were even listed on the roster. So there are parallels, you know, like I was saying about Stacey Salinas' work about the Philippines, about Filipino women kind of being in these guerrilla platoons. We see a similar thing in Alaska as well.

Kelly Therese Pollock 16:34

And we're talking about sort of Natives in Alaska. But that's not a monolith. Right? There's a lot of different groups of Natives within Alaska, you know, what was the ATG drawing from different tribal nations? You know, what, what did that look like? And did they all get along? You know, I assume, historically, maybe they didn't all always get along. But at this point, did they?

Holly Guise 18:38

Yeah. You know, what's interesting is the Alaska Territorial Guard existed predominantly in coastal Alaska, so usually villages and towns in coastal Alaska. And so a large majority of the members were Inupiaq and Yupik, which are the Alaskan Inuit who live along the coast. But, you know, across Alaska, Native men kind of answered the draft call and also volunteered for the service. So we also have like the Athabaskan in interior Alaska, the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian of Southeast Alaska. And then we have the Unanga who were in internment camps in southeast Alaska during the war. So this is also an interesting thing about the Alaska Territorial Guard. When the US military gave guns like World War I era Enfield rifles to the Inupiaq and Yupik, they also had the Unanga in internment camps during this time. So there's kind of a sharp contrast between the ways that certain Native groups are being treated. And I think a lot of that relates to forms of paternalism, you know, like basically thinking that you could protect one Native group by confining them and removing them from a war zone. But that's not recognizing their sovereignty and that's also not recognizing their humanity. So it was a very haphazard plan by the US Navy to relocate the Unanga to internment camps in southeast Alaska. Interestingly enough, a number of Unanga men, when they returned to their home islands after the war, did join the Alaska Territorial Guard. So you can see that Native nations still chose an allyship with the US military during this time, leading into the Cold War.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:30

And so we've been saying territorial guard and so we should put this in context for people that Alaska wasn't a state yet. So this was a territory at the time, and but statehood happened relatively soon after World War II, you know, is there a relationship there between these actions during World War II, and then the the battle for statehood? Or I don't know if it was a battle, maybe the move to statehood?

Holly Guise 20:55

Yeah, yeah. That's a great question about statehood. And, in my opinion, Alaska and Hawaii are both only states because of World War II. So I think during World War II, the US military and government recognized the strategic value of Alaska and Hawaii as being states in the Pacific, and also during the Cold War.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:22

Yeah. Oh, interesting. So we're talking about the Alaska Territorial Guard, but there are also Natives in Alaska, who then sort of join the services and you know, go and fight. So you have also done some work around veterans. Can you talk about that? So are the people in the territorial guard, like, is there sort of a difference? Are they younger and older, or you know, who is deciding to join the service and go overseas? And who is staying home in the guard?

Holly Guise 21:53

Yeah, you know, a number of the guys who were in the last few territorial guard later get drafted, and then join the armed forces. So I think that you could say that when you look at the village population of who's in the Alaska Territorial Guard, it might skew toward the elderly, or also toward the teenage youth who can't quite enlist yet. So yeah, I think that that also might be why some of the some of the age distributions look like that. But I have interviewed a number of veterans over the years. I'm also thinking of Arnold Booth who's Tsimshian from Metlakatla. And he shared a number of stories about being stationed overseas, across the Pacific, like in Papua, New Guinea, the Philippines and Australia. And some of the stories that he shared were really interesting, because at this time, Native men could serve in integrated units with whites, right? So there are ways that Native people are being included in whiteness during this time period. However, Arnold Booth also shared stories about his superior sending him into the jungle first, because he was an Indian, and because the Indian will know, and the Indian can see it, right. So there's these stereotypes of like a, I want to say noble savage, like kind of soldier who's able to see things with Native eyes in the jungle, which couldn't be more different than Alaska. Right. Right. And so there's this kind of irony about the geography being different. But also like, even if this whether this was supposed to be complimentary to him or not, it did put his life more in danger, right than the rest of rest of the guys in the in the unit. So. So yeah, I do remember hearing some of those stories from Arnold Booth. So it's a really interesting time in being in the 1940s, and also where segregation exists in Alaskan towns as well. So Arnold Booth talks about during his oral history interview, I think he was trying to get from Ketchikan to Seattle. I think those were the two locations, he said, and he wasn't able to get a ticket on the barge. I'm trying to remember this correctly. It's been a number of years since I heard it. But he ended up getting a haircut like a military haircut and getting his uniform pressed and ironed and put it on. And then when he went to get a ticket, they got him a ticket to Seattle. So there's also interesting ways that being in the service afforded some forms of equal citizenship rights, right, or kind of equality in public spaces or in businesses.

Kelly Therese Pollock 24:31

So if I sort of understand what happened with the Alaska Territorial Guard correctly, some of the benefits that that you might normally get from being in the armed services, benefits, you know, all sorts of benefits about health care and retirement and how you're buried and all of those sorts of things weren't initially given to the Alaska Territorial Guard in addition to not being paid for their service in the first place. But then there was more recent legislation that attempted to sort of rectify that a little bit. So what why was it that they that they weren't sort of initially recognized for the service that they gave? And what, what sort of changed that why, you know, why are we now, you know, 20 years ago finally saying, "Oh, hey, we should we should recognize that".

Holly Guise 25:26

Yeah. You know, the Alaska Territorial Guard was disbanded in 1947. And in reading Muktuk Marston's book that he wrote that was published, I think, in the 60s, Muktuk Marston kind of gives the first hand account of what it was like visiting these Native villages and kind of working with Native leaders with the territorial guard and when the ATG, that's the kind of short version of it when the ATG was disbanded, Muktuk Marston basically said it directly had to do with discrimination. So basically, military officials did not see these as legitimate units. They didn't really value the volunteer work by these Native men, even though a lot of the work during the war would not have been possible without the Native participation, right, without these Native allies during this time. Native people could have allied with Russia or Japan during this time. Right. So a lot of their contributions to the war effort were disregarded. And there were certainly forms of racial discrimination directed at Native people during this time. But it wasn't until the year 2000 that Senator Lisa Murkowski worked to get the ATG veterans to kind of receive veteran status. Right. So it wasn't until several decades later, and unfortunately, at that point, a number of these ATG members had passed away. But for a number of these men, for example, Wesley Aiken from Utqiagvik up in, the English name is Pharaoh. I remember talking to Wesley, I think his Native name is pronounced Mookie Octorok. And I remember him telling me that he later served in the Alaska National Guard after being in the ATG for several decades. And I think Wesley was telling me that once the ATG was recognized as having veteran status, he got bumped into the next category of having a certain number of years of service. So there were some ATG veterans who were able to kind of add together their military service with their ATG experience added on.

Kelly Therese Pollock 27:35

So we've been mentioning some of these oral history interviews that you did. And I want to make sure people know that they can, they can actually watch or listen to some of them. So can you talk about this, this digital history project that you've done around World War II?

Holly Guise 27:52

Yeah, absolutely. So during my postdoc at University of California, Irvine, I was thinking I really wanted to make the oral histories accessible. And I wanted to kind of make the oral histories available to a broader or more public audience. So something that would also be different than written publications, like books, journals, other things like that in the academic realm. So I, one day I finally just decided to just buy the domain for worldwarIIAlaska.com. So it started with buying the domain. And then from there, I did some research on like, what platform I wanted to use. And in talking to a few other scholars, like, David Fedman was actually influential because he has this website called Japanairraids.org. So I had seen that he had used Squarespace, and he had, it was between that and WordPress, and I decided to go with Squarespace. So I bought the domain for WorldWarIIalaska.com. And it was actually a bit easier than I would have thought to kind of navigate how you would put together the website. So the trickier part came with editing the oral history videos into like 10 minute videos, and creating a YouTube channel, and basically embedding those YouTube videos at the website. So the website has I think about 10, maybe a little more oral histories from Native elders who talk about Unanga internment and relocation, the territorial guard, Native men in the service and also the perspective of Native children during this time as civilians.

Kelly Therese Pollock 29:25

Yeah, it's a really neat website. And now we'd like to play for you some audio from that website. This is a clip with World War II Army veteran, and ATG veteran, Holger "Jorgy" Jorgensen, who's Inupiaq and Norwegian. In this clip Jorgy talks about his work in the ATG. And in the latter part of the clip, he talks about joining the ATG at age 15. The other voice you'll hear is that of Bill Reimer, a friend of Jorgy's, who helped with the interview in 2015. Jorgy gave permission to Holly, to use this audio in any context. If you'd like to hear a more complete interview with Jorgy, you can go to the World War II Alaska website. I'll put a link in the show notes.

Holly Guise 30:16

Jorgy: "When I went to Nome, I went over there because I had joined a territorial guard, and the territorial guard was moving us in places where the defense wanted us to work. In other words, they brought us where they could make use of us. Plus when we weren't working, we were doing stuff with the guard. In other words, we're actually military, well, we were. But because a lot of us knew had grown up in a mining camp and knew how to fish and hunt, they wanted us to work in defense jobs in Nome. They were starting to build an airport. And then a lot of buildings and stuff came up, so we would work for the, for the US Army. And then we would tend to our guard stuff, on, on our days off, which we never got any days off." Holly: "So you just worked every day?" Jorgy: "Right. It was a seven day a week job."

Wow, a lot of hard labor or...?

Jorgy: "No, I well, a lot of it was hard labor but I lucked out. I was running equipment. So my labor was pretty easy because I learned how to run equipment out in a mine and I learned how to weld." Holly: "Wow, so you were welding." Jorgy: "So I be I did a lot of their welding and I did mostly operating equipment." Bill: "So how old were you, Jorgy, when you first started doing that?" Jorgy: "Out in the mine, we started at 12." Bill: "In Nome, you were like 15." Jorgy: "I went to Nome right after my 15th birthday. I joined the guard on my 15th birthday, and I wasn't accepted until, oh, February 2, 1942, is when I got accepted into the guard. And when I got accepted, that's when we went to Nome".

Yeah, my grandfather was in the Alaska Territorial Guard, in Unakleet, Lowell Victor Anagick. And my grandma said that he had a badge and that they gave him a gun. Do you still have any of those items?

Jorgy: "I still have my rifle. That's all. Wow, I still got my rifle in a bedroom back there that was issued to me in 1942."

That's amazing.

Kelly Therese Pollock 32:41

So you work in academia, you're a professor. And I think that this, you know, when you were talking earlier about sort of needing oral history, because that matches the tradition of the people that you are studying. And it seems like this public history, too, is is also sort of follows that same vein. You know, do you think that that sort of the academic world sort of understands and appreciates those differences? There's sort of a certain way that sort of academic historians do things right. There's like a publishing that you do. And you know, but this public history is so important and so interesting. And, you know, are there openings in in academia for that as well?

Holly Guise 33:24

I think and I hope we're moving toward that trend. I really think and hope that we're moving towards the digital humanities, and also public history. It's kind of amazing to me, like having gone through graduate school, and now being where I am now, with teaching, we all possess just a wealth of knowledge about our subject areas, right? It's like, imagine if we could share that knowledge in some way with broader audiences or kind of like a more public facing audience. And so I hope that it continues to move in the trend of making information accessible, and also also engaging, like hopefully these can be teaching resources as well for students, whether they're in you know, K through 12, or college or graduate students.

Kelly Therese Pollock 34:10

Yeah, yeah. Well, I, obviously I love public history, because that's what I'm doing. But you know, I think it's really exciting to see those kinds of things and to be able to point you know, listeners to the podcast to hey, look, you can actually go watch these interviews, too, I think is super valuable. So there are there other topics, things that you wanted to make sure we talked about? We didn't talk about the the piece about kids yet. So if you wanted to go into that as well.

Holly Guise 34:38

The kids piece is an interesting bit because with my writing, I don't actually focus on children's perspectives. But as I was going through my consent forms for who consented to the public facing project, not everyone consents for videotaping, right? Some people only consent to audio recording. Some people will do the interview anonymously. I think over the years I've interviewed like over 75 elders, some over a dozen times. Like Holger Jorgy Jorgensen is someone who I wrote an article with in this Anchorage Centennial Anthology. And it's because Jorgy and I got along so well, you know, like I probably met with him in person half a dozen times in Fairbanks. And then we would talk on the phone pretty regularly. So Jorgy is also featured on the website. So as I was going through, who gave me consent forms to kind of work on the public facing project, I realized I didn't have a lot of Native women who had offered to be recorded and to be featured in a public facing project, and the Native woman who had consented for videotaping and consented to a website, and YouTube video, were children during that time. And so the reason I have the web page featuring the Native children's perspective is because I wanted to make sure that we had Native women's perspectives in there as well.

Kelly Therese Pollock 35:51

And what was their experience like being children, you know, they're presumably not in the Alaska Territorial Guard, but they must be aware of what is happening. And you know, what, what is that experience like for them?

Holly Guise 36:03

Yeah, a number of the Native people who I've interviewed who talked about their childhood, offer stories about the massive militarization of the Alaskan territory. So frequently, Native elders will talk about being children and kind of playing on military equipment with the other kids, right. And sometimes, this military equipment is also off limits. So sometimes you can't access some of these points, like places that would have been traditional fishing grounds. So sometimes you have parts of Native lands that aren't accessible. And then other times you have other types of equipment, right in town, bunkers, other things like that, that you would Native kids would just be playing on. So it's a really interesting time. My grandma is also from Unakleet, Betty, Betty Anagick. And she talks about being a young adult, like a teenager during the war years, and basically the massive influx of military servicemen at a base on Trager Hill, which is right across from town. And so you go from having like this Native village, that's basically probably only had Native people. And then in the 1940s, all of a sudden, there's this influx of servicemen, and there's a base right across from town. But the interesting thing about that base is looking at Trager Hill, you wouldn't necessarily think there was ever a base there. So it's also interesting that some of these military sites have just kind of vanished. And so also on the website, I have pictures of World War II military ruins, to show that some of these bunkers and gunneries are still around on the landscape.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:39

You know, we think about the military and World War II as the first time that American servicemen are meeting, you know, all sorts of different cultures. But it hadn't occurred to me that it would also be the first time for some of them that they would have met Native people. And you know, that's an interesting twist on that as well. I will be sure to put a link in the show notes to your website so that people can can check that out as well. Holly, thank you so much for joining me. This is such a fascinating topic, and and I'm really grateful that you shared your research with me.

Holly Guise 38:13

Thank you. Thank you so much for having me here today, Kelly.

Teddy 38:17

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode at UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook at Unsung History Podcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Holly Guise

Holly Miowak Guise (Iñupiaq) is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of New Mexico. Her manuscript in progress, “World War II and the First Peoples of the Last Frontier: Alaska Native Voices and Wartime Alaska” focuses on gender, Unangax̂ (Aleut) relocation and internment camps, Native activism/resistance, and Indigenous military service during the war. Her research methods bridge together archives, tribal archives, community-based research, and oral histories with Alaska Native elders and veterans.

In 2008, she began interviewing Alaska Native elders about experiences with racial segregation that pre-dated and continued after the 1945 Alaska Equal Rights Act. In 2013, she pivoted to interviewing Alaska Native elders about their memories on WWII Alaska as servicemen, civilians, and children. Most recently, she launched a digital humanities website (ww2alaska.com) that features Youtube videos with oral history content from Native elders, veterans, and Unangax̂ internment survivors. She is interested in the colonial/Indigenous relationship during war and social history.