The Aerobics Craze of the 1980s

In the late 1960s, Air Force surgeon Dr. Kenneth Cooper was evaluating military fitness plans when he realized that aerobic activities, what we now call cardio, like running and cycling, was the key to overall physical health. His 1968 book Aerobics launched the aerobics revolution that followed, as he inspired women like Jacki Sorensen and Judi Sheppard Missett to combine dance with exercise, creating Dance Aerobics and Jazzercise in the process.

I’m joined on this episode by Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, Associate Professor History at The New School and author of Fit Nation: The Gains and Pains of America's Exercise Obsession.

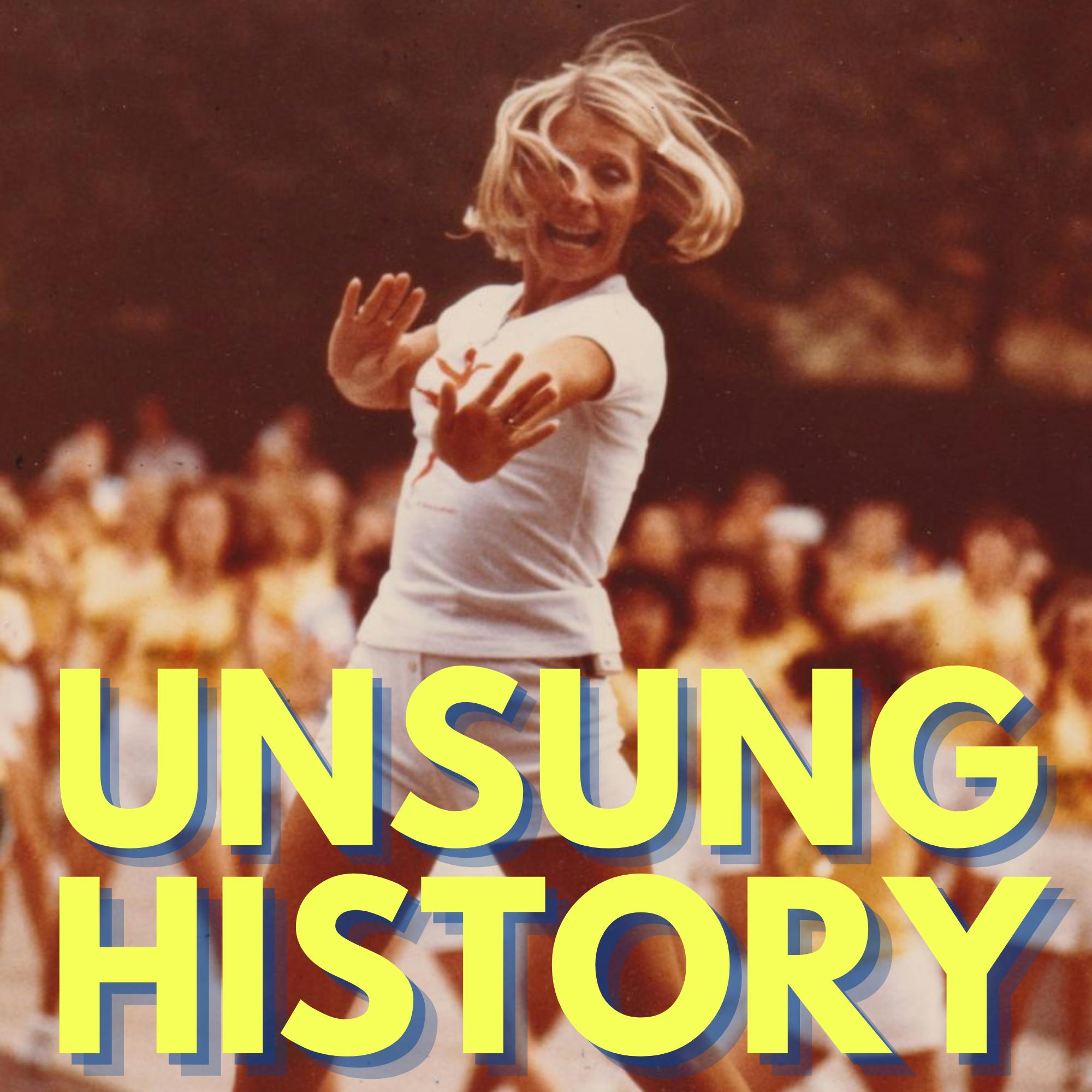

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image is: “Jacki Sorensen at an Aerobic Dancing, Inc., event in New York,” photographed by an employee of Aerobic Dancing, Inc., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Additional Sources:

- “The Fitness Craze That Changed the Way Women Exercise,” by Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, The Atlantic, June 16, 2019.

- “History of Aerobic Exercise.”

- “Kenneth H. Cooper, MD, MPH,” CooperAerobics.

- “The 75-Year-Old Behind Jazzercise Keeps Dancing on Her Own,” by Samantha Leach, Glamour, June 21, 2019.

- “Jane Fonda’s 1982 Workout Routine Is Still the Best Exercise Class Out There,” by Patricia Garcia, Vogue, July 7, 2018.

- “Jane Fonda’s first workout video released,” History.com.

- “History: IDEA Health & Fitness Association.

- “Interview with Richard Simmons,” by Eric Spitznagel, Men’s Health, April 25, 2012.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

Today, we're discussing the history of fitness in the United States. In this introduction, I'm going to focus specifically on the history of aerobics from the late 1960s through the 1980s. And then with today's guest, we'll expand to the longer history that she covers in her book. In the late 1960s, Air Force surgeon Dr. Kenneth Cooper, drew on both his work on physical fitness with 1000s of Air Force members and his own then unusual daily jogging routine, to realize that what he coined "aerobics," or what we would now call cardio was the key to overall physical fitness. Prior to that, military exercises consisted of mostly weightlifting and calisthenics. In 1968, Dr. Cooper published a book called "Aerobics," which included exercise programs, like running, walking, and bicycling. He also developed the Cooper Test, which asked participants to run as far as they could, in 12 minutes to gauge their overall fitness level. Cooper, now age 91, is still the chairman of six health and wellness companies, and the chairman emeritus of the Cooper Institute. In 1969, a dance teacher named Jackie Sorenson moved to Puerto Rico when her husband was stationed at an Air Force base there. She had intended to offer dance classes to Air Force wives, as she had done at his previous postings. But someone there was already teaching dance classes, so she was looking around for something else to teach. Sorensen read Cooper's book, and took the Cooper Test, on which she scored "excellent," despite having never jogged. She realized that dance was an excellent aerobic workout, and she developed an exercise class based on dance. The class was so popular that Sorensen, at the request of Air Force producers, started a television show called "Aerobic Dancing." When she moved to New Jersey, she brought aerobic dance with her. By 1977, about 30,000 people had taken aerobic dancing classes. And in 1979, Sorenson published a book called "Aerobic Dancing." Sorensen's Aerobic Dancing Incorporated hit its peak in the early 1980s, and then couldn't compete with the similar programs that continued to pop up. Around the same time that Jackie Sorensen was developing aerobic dancing, Northwestern graduate, Judy Sheppard Missett was headed down a very similar path. Like Sorensen, Missett taught dance classes, in Missett's case, at the prestigious Gus Giordano studio in Chicago. She started to notice that the moms were sitting to the side while their daughters danced. And she thought about how she could bring the joy of dance to adult women as well. In order to make the classes more welcoming, she focused more on fun and less on technique. And she started classes that she called "Jazz Dance for Fun and Fitness," which later became "Jazzercise." When Missett's family moved to San Diego in 1972, she brought Jazzercise with her. When military wives who took her classes started to move to other locations, they didn't want to leave Jazzercise behind. So Missett created a franchise program, training the women to become instructors and start their our own studios and classes. By 1984, the Jazzercise franchise business was the second biggest in the country behind only Domino's Pizza. The franchise system still exists today and has netted over $2 billion in cumulative sales. In 1982, Peter and Kathy Davis, realizing how fragmented the fitness market was, founded the International Dance Exercise Association, or IDEA, to support fitness professionals. They held their first convention in San Diego in 1984 and established a certification exam in 1985, initially taken by 4000 instructors. The IDEA Health and Fitness Association still exists today, 40 years later, with a membership of 275,000 fitness professionals, and it still offers certification through the American Council on Exercise, or ACE. It was actress and activist Jane Fonda who really popularized aerobics. In 1978, she went to the Body by Gilda exercise studio in Century City, which was popular with actors, while she was rehabilitating a hurt foot. There she discovered how, "Exercise could affect a woman's body and mind." A year later, Jane Fonda's Workout studio opened in Beverly Hills, where Fonda's desire to help women was wedded to her desire to raise funds for California's Campaign for Economic Democracy, a nonprofit organization run by her then husband, Tom Hayden. In 1981, Fonda published "Jane Fonda's Workout Book," which was number one on the nonfiction bestseller list for more than six months, and which remained in the top five for over 16 months. With the promise of raising more funding for the nonprofit, Fonda reluctantly agreed to move into the home video market, releasing "Workout" on April 24, 1982. The VHS cost $59.95, equivalent to about $180 in today's money, and it was the top selling VHS tape for six years. "Workout" and its many follow ups sold 17 million videos in total. Like Fonda, Richard Simmons experienced a breakthrough at Body by Gilda, realizing how fun exercise could be after he'd struggled with his weight for years and had felt unwelcome at men's gyms. But Simmons wasn't welcomed at Body by Gilda, either, perhaps because he was too flamboyant, or perhaps because he was a man in a mostly women's studio. Whatever the reason, he was heartbroken and opened his own studio, "Anatomy Asylum," in 1974. By the time Jane Fonda's Workout Video was released in 1982. Simmons already had a TV show, "The Richard Simmons Show," which included both a workout and life advice, and had launched in 1980. Following the success of "Workout," Simmons joined the soon crowded video market with the 1983 release of "Every Day with Richard Simmons," the first of many such videos, including 1988's "Sweating to the Oldies," the best selling home fitness video of all time, with over $200 million in sales. Simmons worked to help everyone feel welcome in a way he hadn't, including people of all body types in his videos, and even creating a book called "Reach for Fitness," a special book of exercises for the physically challenged, which featured children in wheelchairs, although he had trouble getting retailers to stock it, or to promote events about it. The group fitness landscape has continued to expand since the 1980s, with the introduction of step aerobics, spinning, Tae Bo, Zumba and much, much more. Joining me now to help us dive deeper into American fitness culture is Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, Associate Professor of History at The New School, and author of "Fit Nation: The Gains and Pains of America's Exercise Obsession." Hi, Natalia, thank you so much for joining me today.

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 10:34

I'm so glad to be here. Thanks for having me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 10:36

Yes, I am super excited to talk to you about this book, which I loved. So I want to hear a little bit first about your inspiration, how you got into writing this book, and what it was like for you to sort of mesh these two parts of your life, the academic and the fitness parts.

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 10:54

Right. So I am a 20th Century US historian, I guess, now, I should say modern United States, because the 21st century is very much part of the recent past that I study. But you know, I'd written one book about 1960s, and 70s California, I was always just very interested in that kind of period in American history. To me, it is so much a time I didn't live through like I was born in 1978, but which absolutely shaped the world that I live in today and that I try to understand. So that first book is about educational policy. But I quickly came to realize that the whole kind of wellness world, which is very much a part of our popular culture today, also really germinated in important ways in California in that era. And so that was kind of like the part of the intellectual trajectory that drew me there. But then also, as you alluded to, in your question, I had this kind of whole double life where I was, you know, getting a PhD, and then an assistant professor, but I was also like, not just a gym rat, but I was teaching workout classes. I had found this program, "Intensosity," which to me, kind of represented the best of the fun and energy of group exercise, but like with none of the misogynistic garbage, and I was like really taken with that. And then really bringing those two together, two things happened. One, I started a schools based program in New York City to kind of bring I thought more evolved and exciting exercise and nutrition options to New York City kids, working also on my campus in New York City in that at The New School. And so that was kind of one thing that made me realize, "Oh, I can bring these two aspects of my life together." But then also really, from just like a historiographical perspective, I realized, like not too many scholars that do the kind of work that I do are taking the quote unquote, "gym" very seriously. Like you have people who are like, "Oh, it's just an engine of patriarchy or another site of neoliberal like self fashioning." Okay, fine. Yes. And... And then you had folks who, you know, I thought were like really taking like, almost like an overly academic theorized approach in certain ways, to this aspect of a lot of people's lived experience. And all of that made me just want to dive in and put up with my historian's tools, and understand this world of the gym, which I love, but which is also definitely what the kids call a problematic fave.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:15

Yes. So you decided to go in this direction that this is a super ambitious overview. It's a long period of history that you're looking at with a ton of sources. So can you talk to me about what you wanted to do starting how you started, where you start? You know, why, why you took that entire piece?

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 13:33

Totally. Well, you know, part of it is just like, what kind of intellectual itch you want to scratch, and my first book was like, very much like, you know, it was about 10 years in one state, and it was nationally important, but it was very, very rooted in local archives. So I did have this feeling like I think a lot of historians do with the second book of like, "I want to tell a bigger story, I want to like attempt to like not make sweeping generalizations, but to tell a national story." So there was definitely part of that. But then honestly, the topic of fitness lends itself quite well to that kind of broad framing in that, you know, this was a national movement, like no pun intended. This was a situation where yeah, you have like certain like, loci, I guess, New York City, Los Angeles, some other places where that really germinated this, but especially through technology, television, VHS, it very quickly became a kind of national movement. And so you could tell local stories that sort of encapsulate really important aspects and even evocative aspects of fitness in America. But I was like, "I think I'm up for tracing how this thing moved from place to place and what that looked like." And then in terms of the amount of time that I cover, yeah, I started in 1893 and come to the present. For me, that seems just like wow, that is so much time to cover right? On the other hand, it's really funny because some, you know, kind of pure titles that aim to look at the history of fitness, they start with like the Greeks, right? Or they're looking at like, cave drawings of like women with these, like things that look like barbells. And there is a tendency with this topic to kind of almost take like an evolutionary biology take on things and like, look at that really, really broad span, I find that helpful. But it's not the it's not the way my brain works. Like, I want to be in the sources. And so the reason that I started when I did 1893, World's Fair, Chicago, is, I just thought it was like such a rich moment to draw people in to a time when exercise was very much about performance. Like you would pay to see someone on a stage who lifts weights. And that's entertaining and weird in the way a bearded lady is weird, but it's certainly not something you're you're going to do yourself. And, you know, I was so grateful to University of Chicago Press for letting me have a lot of images for a book like this, because one of the funny things is that Eugen Sandow and these other strong men who were up on stage at that time, like, you know, they look good, they look fit, but they look like any guy who lifts every day at the gym in your town. And I think that like shift in body norms, and what's aspirational, and what's considered freakish is another part of this story, that images really helped me tell.

Kelly Therese Pollock 16:12

Yeah, I loved the imagery. And so let's talk sources some then too because you have a number of totally disparate kind of sources. And you also have interviews. And I'm assuming you also did things like watch the Jane Fonda Workout video and stuff as you were writing the book. So talk to me about how you figure out with this huge span of time and place, how you figure out which sources to dig into and how to tell that story.

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 16:38

It was really hard, because, you know, we have this historians' inclination, which I think is a good one to, you know, turn every page and you're not done till you've looked at everything. That, of course, is impossible with a national story that spans over a century, and also impossible when you're looking at recent history, and there's just so much that is generated. So I tried to be really judicious in picking collections that I thought would tell me something bigger. So some of that, for example, I looked, I went to NIRSA, which is in Oregon, the National intramural and Recreational Sports Association, I think it changed what it meant at some point. But that's the basic idea. And like, that was a really worthwhile collection to spend a few days in because that was an organizing committee that was working with campuses all over the country. So when I looked at their annual meetings, etc, I got to see like, "Oh, wow, HBCUs were really important places for this kind of work to happen." And I could do that without going to like 30 different campuses. That was one set of sources. Another thing that was really important to me, and was a little less systematic, quite honestly, is that because I had worked in the fitness industry, and been writing about this kind of journalistically, I have a lot of contacts. And because a lot of these kinds of materials that chronicle the history of this field, are not considered worthy of being in the National Archives, and not considered the sort of things that get put in formal collections, I was like in basements, and had people like sharing Google drives and texting me photos on their phone of like the brochure of the conference that they organized. And that's obviously imperfect in terms of like, I've turned every page and looked at every person, but I do think that it's unique. And I do think it is important, and I tried to be appropriately humble with my citations and sort of like, the limits of the conclusions that I was drawing about things to, you know, show where this came from, and what you can and can't say from it. Then, you know, there was the matter, particularly in the pandemic, and I also have young kids of just like, what's available, right, and we all always have to make those choices. For me. I mean, the digitization of so many press sources was just invaluable, just amazing. And I mean, the mainstream ones Los Angeles Times, New York Times, etc. But much more than that, I mean, a shout out to ProQuest, Alexander Street, like all of these aggregators, you know, the Ethnic NewsWatch, like all of these ethnic newspapers, like Google Books, and Life magazine, Ebony, Jet, I mean, this was really incredible. So that was really, really important for me too. The last thing that was really unfortunate is that I never got to go to the Stark Center in Austin, Texas, which is this, like, amazing repository of what I hear is an amazing repository of physical culture items, and just because of the pandemic. I was set to go like, right when it started, it was gonna be my last research trip. Luckily, they have some really good stuff online. And so I got to use some of that. But that is, if I ever were to do a follow up, that's the first place that I would go. So you know.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:35

You mentioned at the beginning, that you're a historian of the US and this is such an American story. I feel like in so many ways, this is the story of American culture. It just happens to be through the lens of fitness. So can you talk a little bit about how American this is, how rooted in American culture and American history, the story of US fitness is?

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 20:00

Absolutely and what a challenge! I mean, the New York Times Book Review, the last paragraph was like, what about the rest of the world? I'm like I tried. And I think you're right, I tried to show how it was meaningful to stay within these national borders of the United States, because it is so distinctly American. Why is it so distinctly American? Well, there's this philosophical dimension, I think, where if we think and it's a bit cliched, but cliched because it's true, that like so core to American ideology is this idea of individual self help, of bootstrapping, of like, you know, the self made man and later woman. Fitness is like, the perfect set of ideas and activities through which to embrace that sensibility, right. Like, you know, I try to show it's not just individual will which shapes your ability to, you know, participate in fitness activities, or what your body looks like, but of, like a lot of activities you can participate in, it's a pretty appealing one, right? All it takes is willpower to get up and go for your run or do your sit ups. So you know, save enough money to join this gym if you care about health. And so there's this profound individualism in American fitness culture that I think really kind of solidifies how it becomes American. Then there is also I think, the particular mythology and image making and really self mythologizing around California, that becomes so central to American fitness. And this idea of the beach body, and a kind of healthy lifestyle that, really comes out of California. Third piece is that I would connect the kind of Americanness of fitness culture to the kind of global exploitation of pop culture throughout like the latter half of the 20th century. Really, in the same way that American movies and products like Coca Cola have come to be consumed all over the world, and kind of aspirational, fitness becomes one of those things like American Fitness, VHS and beta then too, and other formats. Also, these become desirable American exports. And this is something that, you know, kind of works if you're studying geopolitics, and it kind of fits into that idea. But there was such amazing human stories that I discovered through this. I was interviewing one woman, Monique Dash, and she talked about, she had been a dance major in college in the early 80s. She saw this ad to sign up and go teach aerobics in Italy. And so she was like, alright, she's this girl from the Bronx. And she learns a little Italian and she gets there. And she's like, ready to be like, "Oh, I'm gonna work at the gym through the aerobica." And like, no, no, you refer to it in English because people were coming to have a Jane Fonda style aerobics class. So I try to, you know, show how that happens, but also not be too myopic, or ethnocentric in the way that a lot of Americannists and Americans can be. And like Eugen Sandow, the strong man who I started with, he's Prussian. Like a lot of a lot of American physical culturalists came from Europe or taking inspiration from there. That goes on throughout the whole time I chronicle. There's a reason Zumba is so popular in a lot of ways, because it's this like Latin import. Same with yoga, another major trend that I that I chronicle there. For me, it was important, and I hope I did it well to kind of like articulate the distinct Americanness of this story while saying America exists as part of the rest of the world. And this is what that meant, in little bits and pieces globally. The last thing I'll say that, which I think is like a, you know, a big theme in this book, which I think is important, and points up that kind of international context being relevant, is the kind of missed opportunity of a truly public national commitment to the provision of fitness. And that was a really fascinating thing to uncover in the archives, this mostly through government archives, tracing this, these committees around physical fitness, where, you know, there was this moment of enthusiasm in the 50s and the 60s around sponsoring federal PE as part of like a Cold War Project. But a lot of what wore that down was the sense that like, "Oh, like managing the body, big group exercise, expositions that's like fascist or communist or something, but it's certainly not American." And so in another, like highly American move, you have that, you know, exercise equals virtue idea definitely got embraced, but it's like, totally a private industry that runs with it. And it's like, if you can pay to be part of this. Sure. But we're not paying for this as a national project, because like, we don't do that.

Kelly Therese Pollock 24:23

Yeah. And so I want to pick up on that private industry piece, because the money behind all of this is so important to this story and the economic story of what happens and how this happens. And who benefits from this and who does not benefit from this is a crucial piece to it. So talk to me about the economics and what you found in the archives as you were looking at this.

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 24:48

Yeah, absolutely. And so I think in many ways, the fitness story just bears out a story which other phenomenal historians of inequality have been telling, which is that, you know, in the late 20th century we saw the rise of austerity politics, and we saw the cutting back of a lot of different kinds of, of public and social programming, and what did that serve to do? It served to deepen inequality in our country. And lots of other people have written about that in terms of housing and education, and food also, as well. And so this book in some way, says "hey also fitness" and points in many ways to the stripping back of funding for physical education, public recreation, like pools, well lit, parks, running spaces, etc, while at the same time you have this booming industry. And I think like some other realms, but maybe even more intensely so in fitness, there is this like, real tension. And I think it's like a really tragic and insidious tension that exists between we're in a culture where we're constantly talking about how virtuous it is to exercise, and by extension, how immoral and lazy and disgusting it is to not, and even to look like you don't. And yet, we don't embrace that idea enough to actually provide those funds to make it a public good. And that's the thing I'm going to draw people's attention to, because one of the things I first discovered, like, particularly when I was teaching, and I still do teach history of education, kind of classes in education studies, a program I used to be in, I found that there were a lot of people who were like, pretty sympathetic to the idea that race is socially constructed, like, you know, structural racism is a thing, misogyny and the rest, but then they'd be like, "Ah, but obesity, like those people need to make better choices." And I'm like, "wow," you know, and it's like, that conversation just hasn't fully arrived to the realm of the body. And I think a lot of people working on food have done an incredible job at kind of parsing the way that works. But I hope this I see this as a kind of relatively early contribution to do that in the realm of fitness, because I don't think that we've really had that conversation yet.

Kelly Therese Pollock 27:00

Yeah. So you're talking to me about race and class here, I want to talk to you about gender, because that's such an important piece of this, how gendered all of this is and the way that it's acceptable for women to work out versus men and the expectations on women and men are different. And even the ability to make significant money doing this is different, depending on your gender. So can you tease that out a little bit?

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 27:26

Yes. And first, I should say that, you know, the story that I tell is one that really exists in a moment when people are talking about gender as a binary thing. So like, I just want to point that out. I think my work reflects what's in the sources. But some of it just feels not just historical, but out of step with the way we talk about gender today, and even the way the fitness industry does. So I'm just putting that out there. Yeah. So the first part of the book is basically dedicated to explaining a time when, as I alluded to earlier, like sweating was strange. And, you know, it was not virtuous to go to the gym, and it was looked down on in different ways for men and women. So to get to your point about gender, if you were a man who wanted to work out, well, you know, that is not cerebral, it's narcissistic. It's not like a sport that's competitive and virile. It's like, kind of effeminate to care so much about your body, like what's wrong with a guy who wants to do that, and a guy who wants to spend time among other men who want to do that too. And that's very important. In a moment when there weren't gyms everywhere, and the notion of a gym bro, as like a straight guy didn't even exist, there was real suspicion about the spaces where men gathered to exercise. And I should say that suspicion, homophobic as it was, was sometimes grounded in the reality that in a moment when people were forced into the closet by homophobic public policy, physical culture spaces were places that men who sought the company of other men romantically would gather. So that's kind of complicated and interesting. For women, it looks different the way that women were discouraged from exercise. And there the idea was like, "Well, you know, there's a big physical risk to women for exercising, like, you know, their uteruses could fall out. And a woman who can't have a baby is just like, not even worth living. Who would want that? Also, muscles are going to make women look, you know, unsightly and masculine. And then the third piece is almost more philosophical, that you know, doing kind of rigorous individualistic work is going to like make women cultivate these like unladylike sensibilities. And so what's interesting there, so you have that kind of foundation. So there is though this interesting way in for women, and you see that with like, women's and girls' phys ed advocates, one of the things they do is they introduce like these ideas of group dance, right? And they say, "Oh, this is like about grace and community and like group activities, and it's very gentle. It's better than having them do all these intellectual things, because we don't want to cultivate these girls so think they could be scholars like let them work on group dance." So there's that way in. And then I think even more powerful than that, and is so relevant and still with us today, there is the idea that, "Well, okay, we don't really want women to be sports women, but we do want them to be pretty." And to the extent that exercise can be a form of bodily self management to be attractive, well, then it's more than okay. And so there's this really fascinating thing that happens in 1930s, 40s, 50s, 60s, even where you have these studios and salons which prefigure the ones that we have today. But they are very much connected to beauty work, like some of them are even connected to beauty salons, you get your nails done, and then you go to a reducing spa and have like your cellulite shaken away, or a very gentle kind of dance kind of ballet inspired workout. But I say like very gentle like ballet, I shouldn't probably be using the same in the same language. But I think that that's super important because it was an important way in through the beauty industry, but one that was very, very circumscribed by, you know, women like you should see these ads. I mean, you'll see them in the book, read the book, everybody, but some of these ads are like, you know, "No sweating required. Relax in luxurious comfort." Like they just had to be very careful to say this wasn't actually exercise.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:15

Yeah, no, it's so fascinating. So you mentioned that you were born in 1978. So was I and the '80s, and the fitness of the '80s is just sort of so overwhelming, in my mind. Full disclosure, my mom was and still is an aerobics instructor. And so this was the 80s were filled with this for me. And I remember her going to an IDEA convention, for instance. So this, this is sort of part and parcel of my childhood. But I wonder if you could talk about that moment, the 80s, and the Jazzercise and the dance aerobics and everything that happens then, and how that sort of helps get women a little more front and center in this movement, because they really do then sort of take over a lot of this space.

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 32:00

Yeah, so you know, aerobics was so important in the 1980s. And there's this oft cited fact, which I think is true. I've checked it with that, by the mid 80s, 22 million Americans are doing aerobics, most of them women. Why is this such a big deal? Well, in 1970, dance aerobics, like barely existed as a concept and as something so big, like, absolutely not. And then the fact that even men were going into some of these choreographed classes as well, and that they were in movies. And it was such a moment, like, I think few people could have seen that coming. So to me, that era is so interesting, because, you know, at the same time, it is a kind of triumph of feminism, and you never would have been able to have these predominantly women's spaces doing like girly moves, right? Like, because girls or girls and women usually grow up doing dance classes much more than boys and men do, You wouldn't have been able to have that, I think without the feminism of the 1970s, particularly Title Nine, where so many feminists argued about women's bodily strength and ability to compete like boys would without really a lot of the kind of body centered movement of 1970s feminists, as well as the efforts of feminists around equal pay and fair credit, right in order to be able to have money to spend on their own, not to need their dad or their brother or their husband to come sign for a credit card for them. So I think that all of that was super important. Now, what I find equally interesting, or like, a component you cannot forget, is that a lot of the reason though, that dance aerobics was so appealing to people was because it wasn't like all that feminist. Like, you're still in there, like, you know, gyrating your hips and wearing these cute little outfits and like, really, you know, trying to lose weight as basically all of them advertised in those days. And there was something I think, definitely extremely liberating about those spaces. Like, I'm the first one to acknowledge that, but I think it's so fascinating that kind of feminism enabled them to thrive, but what drew a lot of people in was actually that they weren't that radical, like, I don't want to be a jock, but I want to go do leg lifts, right? Like and I think that some of the, I think the impact, no pun intended, because there's a whole injury story there too. But I think that the impact of the kind of dance aerobics phase was in some ways a kind of like, unwitting feminist triumph in certain ways. Like Jane Fonda definitely saw this as part of a feminist project. Like she writes about that very explicitly. She was obviously very influential. But she writes about that in her book, you don't really see that so much in the videos. That is what most people saw. And then in other big programs, Jazzercise and otherwise, you don't see that explicit feminist kind of articulation at all. And I think that a lot of women did find like, "Oh, my God, spending time on myself dancing in the company of other women, dropping off my kid and taking this me-time." I don't think we should underplay how incredibly important that was, and that's for the women attending as participants, but then like your mom, but also like, you know, 1000s of Jazzercise franchisees in the people who made up the profession, there also was this liberatory dimension of this new job position, right, which was being an aerobics instructor. Now, I think that was a huge deal. And some of the women and men but mostly women who I interviewed for this book, blew me away with this insight that I kept hearing, which was, you know, these are people who graduated from college in like the late 70s. And they would say things like, if I'd been born 10 years earlier, I would have been a PE teacher, but I was born and in this moment, and I came into this industry, and there was this appetite, and I like made tons of money. And I was a celebrity that was a magazine covers. And that was unheard of, for a kind of jockey girl with teaching fitness ambitions 10 years earlier. And I think that that is really, really incredible. And we should focus on that. But I also think it's important to realize how much it was then, and still is now a superstar economy, and that most people who are teaching fitness, especially women are gig laborers, they're made make very little money, they don't have benefits, there's almost no labor solidarity, in the way we conventionally think of with unions. And that's super gendered too. Like, it was often thought of like, this is like pin money, you're just making a little extra something for you to do while the kids are at school. And for some people that really was what it was. But as we know, from long histories of women's labor, that's so commonly a way to, you know, rationalize paying women less. And one, again, like very concrete point that comes out of the archives, and I love it when like these big ideas are so backed up with this awesome data I was lucky to have access to, one thing that really draws attention to that is when the professional certification of personal trainer is born in the early 1990s. Well, then men start to come into the game because it sounds clinical, almost medical, it's not like being in this feminized space of education, and the money starts to be much more as well. And I think, you know, personal trainers are not making zillions of dollars. But it's a really interesting juxtaposition between the aerobics instructor who's kind of a celebrity but like also sort of degraded like this ditzy gym bunny versus the personal trainer who's like this clinical expert. So yes, super interesting the gender part, for sure.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:11

So I want to ask about the pandemic because, of course, that that is part of this book as well. And I think that indications, and you're right about this at the beginning of the pandemic, were maybe this was going to change things forever in the fitness industry. And I'm not sure that that it has. So I wonder if you could talk through that a little bit?

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 37:29

Yeah, well, I do think that the pandemic has changed the fitness industry in that home fitness really accelerated in its development in a way that you know, I don't think would have happened if we hadn't had all these lock downs, etc. So you really have had a really a real boom in that. And then I also think that closures and people's anxieties about going back to brick and mortar stretched on for so long, that people who could afford it really invested in setups at home and created new habits. Remote work isn't going away for a lot of people. That's really changed the way that a lot of people exercise. That being said, we're seeing brick and mortar gym numbers bouncing back. People are going back to the gym. And so I think in that sense, like people were forced to think about what does fitness mean to me? What's important about it, and my sense a little bit from my own life, but also from talking to a lot of people is, "Wow, the convenience of at home fitness is just like unparalleled, that's amazing. But there's a lot more that I get from working out than just completing like the 45 minute Peloton ride or whatever. And so I what I see kind of starting to happen is that people are creating these like hybrid programs for themselves. And I don't mean hybrid, like they're logging in somewhere and doing it at home. I mean, you know, maybe three days a week you're working out at home, because it's really convenient, you can do that. But then there's like a destination experience that you're having where you're like, "Oh, this is a class and I love the people and the instructor and the music and the smell of the towels." And maybe you're spending a little more money going a little further and it's more of an excursion. So I think that that's probably going to continue, but then perhaps more momentously for this issue of inequality that I care so much about. I mean, everything I just described is available to people of a certain social class, having control of your time, having space, having the option to have this like cocktail of in person and at home. Like all of that speaks to a great degree of consumer privilege and purchasing power. And really the big pandemic fitness story which I see as like so tragic, isn't like for all the talk about Peleton and at home workouts and getting my pandemic body, blah, blah, blah. So many people, public facilities were closed longer than anything else. You know, playgrounds taped up, basketball hoops taken down, all of that affected people who don't have the space to do so at home kind of even more, phys ed obviously closed in schools. And so we have seen a continued you know, issues related to obesity and other sedentariness data bears out that the pandemic has only kind of increased fitness inequality. And that is sad, but not surprising at all.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:29

Yeah, yeah, I live in Chicago and the lakefront was completely closed off for like months. And now of course, knowing what we know about the pandemic, that would have been the safest place to be.

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 40:16

I know I know that and I find that so frustrating. And I think there was a little bit of posturing in some big cities, New York as well of like, "Oh, look, we're doing so much for the pandemic. We're like closing down beaches and parks etc," as if that was like this grand gesture that was doing anything, except being a gesture and actually really limiting people's access to exercise and that I find so unexcusable and I don't think anyone's gonna apologize for it, but I can keep screaming about it.

Kelly Therese Pollock 40:44

So hopefully, everyone will understand by now that they must read this book. So how can people get the book?

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 40:49

The book is available anywhere books are sold. So you can go on indiebound, or on Amazon or the University of Chicago Press site. And I should say, depending on where you are, I have events on the calendar confirmed right now. Boston, January 18, Brookline Booksmith; The Strand in New York on January 10;, both in conversation with incredible writers, and there are more of those coming. So definitely stay tuned. I'll post them all on my social media.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:15

Excellent. And I should note, this is being posted at the beginning of January when people probably have all sorts of ideas about what they're going to do to get in shape in the new year. So what are some parting words that you might have for them?

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 41:30

Absolutely. I didn't mention I am a fitness instructor too right. And for me, the most important thing at the beginning of the year is, "Yes, absolutely make new promises to yourself. But if you want to keep them think about what you actually will do, as opposed to what you wish you would do." And so I think my mantra is kind of that no opportunity for exercise is too small to be worth it. And so what that means, "Oh, you want to catch up with a friend usually get coffee, why not go for a walk together?" Right? I have a pull up bar visible in our little zoom here. I try to knock out a few every day just to get a little stronger. It takes literally five minutes. But to me that is worth it. So do what you think you will do rather than what you wish you would do.

Kelly Therese Pollock 42:10

Yes. Well, Natalia, thank you so much. I loved this book, and it was so fun to speak with you.

Dr. Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 42:15

Thank you and it was great to speak with you too. I really appreciate it.

Teddy 42:20

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela is a historian of contemporary American politics and culture. She is the author of CLASSROOM WARS: Language, Sex, and the Making of Modern Political Culture (Oxford University Press, 2015), and FIT NATION: The Gains and Pains of America’s Exercise Obsession (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming 1.6.2023). She is co-producer and host of the acclaimed podcast WELCOME TO YOUR FANTASY, from Pineapple Street Studios/Gimlet and the co-host of PAST PRESENT podcast. She is a columnist at the Observer, and a frequent media guest expert, public speaker, and contributor to outlets including the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN, and the Atlantic.

Natalia is Associate Professor of History at The New School, co-founder of the wellness education program Healthclass 2.0, and a Premiere Leader of the mind-body practice intenSati. Her work has been supported by the Spencer, Whiting, Rockefeller, and Mellon Foundations. She holds a B.A. from Columbia and a Ph.D. from Stanford and lives with her husband and two children in New York City.