The Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II

From September 1942 to December 1944, over 1000 American women served in the war effort as Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), flying 80% of all ferrying missions and delivering 12,652 aircraft of 78 types. They also transported cargo, test flew planes, demoed aircraft that the male pilots were scared to fly, simulated missions, and towed targets for live anti-aircraft artillery practice. The WASP did not fly in combat missions, but their work was dangerous, and 38 were killed in accidents. Even with the enormous contributions they made in World War II, the WASP weren’t recognized as part of the military until decades later when they were finally granted veteran status.

Joining me to help us learn more about the WASP is Katherine Sharp Landdeck, Associate Professor at Texas Woman's University, and author of the definitive book on the Women Airforce Service Pilots, The Women With Silver Wings.

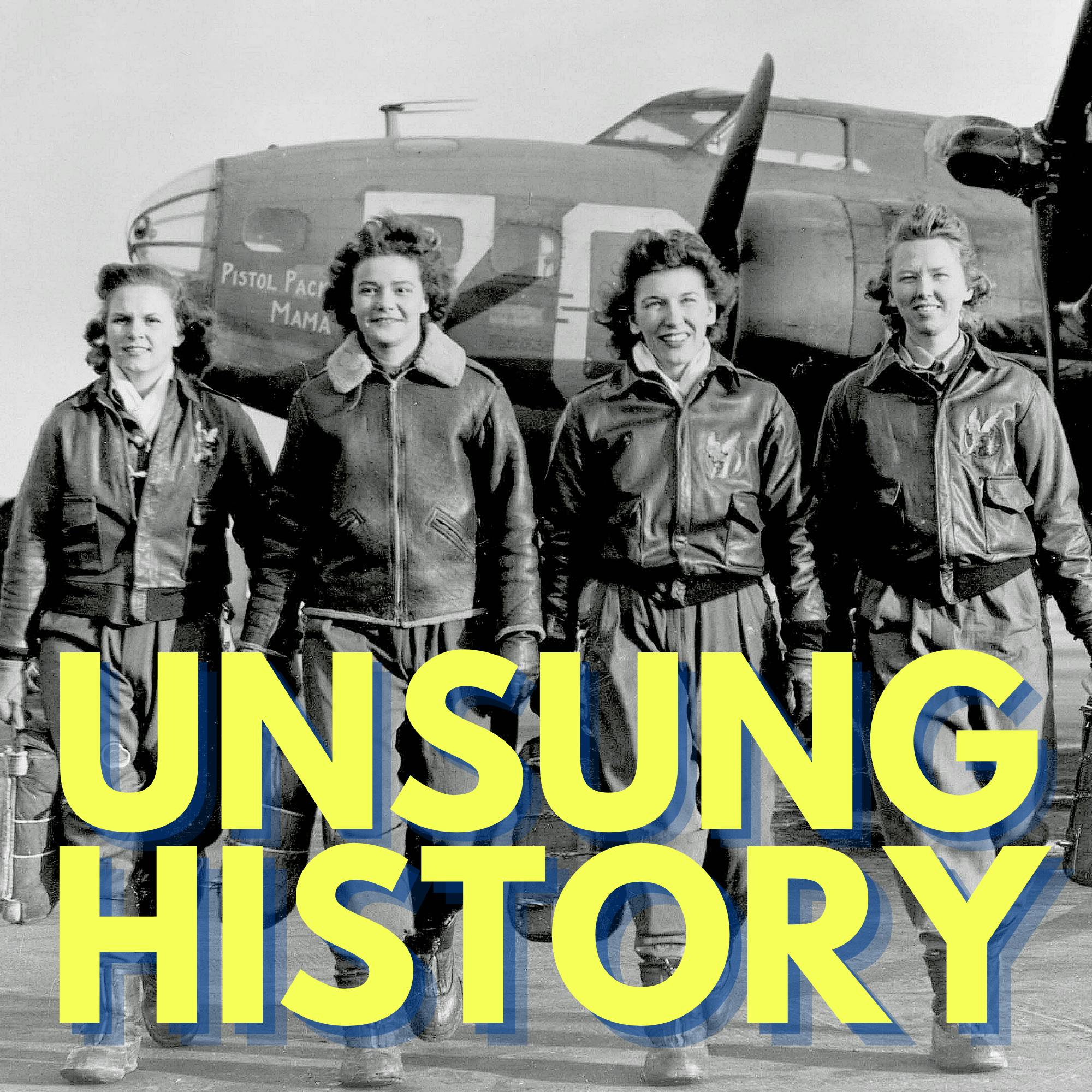

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. Episode image: “WASP Frances Green, Margaret Kirchner, Ann Waldner and Blanche Osborn leave their B-17, called Pistol Packin' Mama, during ferry training at Lockbourne Army Air Force base in Ohio. They're carrying their parachutes.” from the National Archives and in the public domain.

Selected Additional Sources:

- Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), Women in the Army, US Army.

- “Female WWII Pilots: The Original Fly Girls,” by Susan Stamberg, NPR, March 9, 2010.

- “Remembering the WASPs: Women who were aviation trailblazers,” CBS News, June 1, 2014.

- “Flying on the Homefront: Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP),” by Dorothy Cochrane, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, May 20, 2020.

- “Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) of WWII: STEM in 30 Live Chat [Video],” Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, September 12, 2020.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. Today's episode is about the Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASP), a civilian organization of women pilots during World War II. Formed in September, 1942, the WASP had two arms: the Women's Auxilary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), and the Women's Flying Training Detachment (WFTD). The Women's Auxilary Ferrying Squadron was led by Test Pilot Nancy Harkness Love. Love was working in a civil service position in the Operations Office of the Ferrying Command's Northeast Sector, while her husband, Major Robert Love, was on active duty in Washington, DC. Colonel William H. Tonner, who commanded the Domestic Division of the Ferrying Command, noticed her flying skills as she commuted by aircraft each day to Baltimore. Tonner had been searching for additional pilots to help in the war effort, and Love convinced him that experienced women pilots were the right fit for the job. He appointed Love as Executive of Women Pilots, and she set about recruiting and training women to deliver planes from factories to military bases. At around the same time, pilot Jacqueline Cochran, who had been recruiting women pilots to serve in the British Air Transport Auxilary, convince General Hap Arnold of the Army Air Corps, that the US military would need to train more women pilots. She organized the Women's Flying Training Detachment, (WFTD) to train women who weren't yet as well qualified, so that they could prepare to join the Ferrying Division. By summer, 1943, the women pilots were doing more than ferrying planes, and they needed a name that reflected their duties. On August 5, 1943, they became the Women Air Force Service Pilots, which fit General Arnold's desire for a nice acronym, WASP. Cochran served as Director of WASP and its Training Division and Love was Director of the Ferrying Division. WASP recruits needed to be under the age of 35, in good health, and at least five foot two inches tall. They needed to already have a pilot's license and at least 35 hours of flight time. Over 25,000 women applied to join the WASP. Of the 25,000 applicants, only 1879 candidates were accepted into the program. 1074 candidates, over 57%, successfully completed the program, which was a better completion rate than male candidates. The training the women received was very similar to the training men aviation cadets received except that the women did not receive gunnery training, and had less in the way of formation or aerobatic training, since they would not be flying in combat. Many of the WASP recruits, though not all, were from fairly well to do backgrounds, which is how they had afforded earlier piloting experience. Most were white, although there were two Chinese Americans, two Latinas and at least one Native American woman pilot in the program. African Americans were not welcomed. Cochran told one African American applicant in her interview that, "It was difficult enough fighting prejudice aimed at females without additionally battling race discrimination."

Among other important duties, the WASP continued to ferry airplanes. During World War II, women pilots flew 80% of all ferrying missions. The WASP delivered 12,652 aircraft of 78 types between September, 1942 and December, 1944. The WASP also transported cargo, test flew planes, demoed aircraft that the male pilots were scared to fly, simulated missions, and towed targets for live anti aircraft artillery practice. All of these duties carried risks, and 38 of the WASP members were killed in accidents: 11 in training, and 27 on active duty missions. Because the WASP members were not considered part of the military, the military did not provide any honors, such as US flags by the coffin and the military did not even pay for the funeral, or the expense of transporting the body home. There were various efforts to bring the WASP formally into the military, although there was also opposition from civilian male pilots, and not everyone in the WASP agreed on what militarization should look like. HR 4219, a US House Bill, which would have provided the WASP with military status by making them a women's service within the US Army Air Force, was defeated 188 to 169. On December 20, 1944, the WASP was formally disbanded. General Hap Arnold wrote to them, "When we needed you, you came through and have served most commendably under very difficult circumstances; but now the war situation has changed, and the time has come when your volunteer services are no longer needed. The situation is that if you continue in service, you will be replacing instead of releasing our young men. I know the WASP wouldn't want that. I want you to know that I appreciate your war service, and the AAF will miss you." In 1977, the WASP were finally given military recognition when they were granted veteran status. The Department of Defense had supported the bill while the Veterans Administration opposed it. Senator Barry Goldwater, who had flown with the WASP during World War II, championed the bill and attached it as an amendment to the GI Bill Improvement Act, HR 8701 in October, 1977. Since the discharge papers for WASP Helen Porter had read, "This is to certify that Helen Porter honorably served in active federal service of the Army of the United States," the amendment stayed, and President Carter signed the bill into law on November 23, 1977. To help us understand more, I'm joined now by Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck, Associate Professor of History at Texas Woman's University, and author of "The Women with Silver Wings." So Hi, Kate, thank you so much for joining me today.

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 8:40

Well, thanks so much for having me.

So this is a really cool story. And I'm excited to talk about it and to talk about it with you. I wonder if you could tell the story of how you first got interested in the WASP because, you know, you mentioned at the end of your book, there's just a little you know, sort of brief mention of it, but it sounds like a fascinating story. So if you could could tell us a little bit about that.

Sure. You know, it's one of those moments in time that, you know, if you hadn't done something your whole life would have been different. It's one of those great turning points and, you know, basically I was in Tulsa, Oklahoma, I was teaching at Spartan School of Aeronautics. I was teaching history and government for their associate degree program, had a fresh, shiny new Bachelor's in History and a shiny new Bachelor's in Political Science, I was a double major. And there was an air show up the road in Bartlesville, The Bartlesville Biplane Expo. I couldn't get anybody to go with me. I worked at a flight school. I had all these friends who were pilots and aviation geeks. None of them would go and I decided, "You know what, I want to go." It was a sunny, you know, June day in Oklahoma. And so I went by myself, and it was the best thing I ever did. And I highly recommend going places by yourself because then you get to do what you want to do. So after the air show, I kind of hung around and was peeking in an airplane. And it was a Pitt Special, which was, is one of the best aerobatic planes ever designed. It's just a really great little airplane. I was kind of peeking in it and the pilot came over and I was a little nervous like, oh is are we going to? You know, is it going to be mad at me, you know. And this again, this was very a long time ago. This was in 1993. So a long time ago, I was quite young. And he's like, very friendly, very nice. And he said, "Hey, over in the shade of that hangar over there. It's Curtis Pitts, the designer of this plane, and you should go say, hi. He's nice. Oh, I don't know. And he convinced me to go do it. And this was my day of being bold, so why not? And so I walked over and I'm, I'm sure I said something clever like, "Hey, Mr. Pitts, you make an really neat airplane." You know, it's very sophisticated, and what I did, but he was just the nicest guy and talked to me for a very long time and introduced the woman sitting next to him as Caro Bayley Bosca, the 1951 International Aerobatic champion in his second airplane. And I was stunned. I loved airplanes, I worked at a flight school, and I had no idea that women flew in the 1950s, and that there have been aerobatic competitions with women. So I spent all this time talking to them, and then asked if I could have my picture with them. And that picture is in the book, I think. And as we were finishing and walking away, some crazy woman, and if you believe in time travel, it was me, because she was kind of middle aged and had crazy dark hair, and ran up and said, "You're Caro Bayley Bosca. You were WASP in World War II, you flew B 25s and all these planes." And I was stunned. I'm like, "What are you talking about?" And, and that was it. I started I talked with Caro a little bit about it. And she gave me her name and address on a note card. This is before email was popular, and all of that right a long time ago back in the dark ages. And and she said if you want to learn more, write to me. So I spent the next three years learning everything I could, finding the very few books that had been written. And then I finally wrote to her. I went to graduate school so I could learn to write history the right way, because I wanted to know their story. And I wrote to her and said, "You may not remember me but...," and she invited me, the WASP were being inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame in Dayton, Ohio. And she said, come on up and gave me the name of Nadine Nagel, who was the WASP in charge and said, "You know, be nice to Katie," and and then Nadine got me set up in the hotel and got me, you know, introduced me to the WASP. And that's that's the weekend I started my oral histories in 1996. So it was just one of those, if I hadn't looked in that plane, if that guy hadn't encouraged me, if if Curtis Pitts hadn't been nice, and Caro hadn't been sitting there, you know, I, I don't even know where I would live. I have no idea what I'd be doing with my life. And it's not very often you have a photograph of that moment in time that that changes everything. But But yeah, I feel very grateful. Now, that's a long version of the story. But...

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:25

No, no, it's an incredible story. I love that. And it's so rare for someone to have the project first and then decide to go to graduate school. You know, so often people are like, "Oh, when I was in grad school, I discovered..."

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 13:37

Right, right. I highly recommend it. It goes much faster.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:41

I'm sure. So this this story in your book is so incredibly detailed. So you just mentioned oral histories, what what are all the kinds of sources that you use to piece this together?

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 13:51

Yeah, so the thing about the story of these women is it really hadn't been told broadly, right? There were, you know, some of the WASP had their letters and wrote little memoirs and things like that. But Sally Keil had written a really good book on just the general history. But I you know, there was so much that was missing in the WASP story. And I really, I came at it in kind of an odd way, because I was really interested in what they did after the war. And I'm sure that's because of that's, that's how I met Carol was. I was introduced in 1951 to these women pilots. And so it's like, well, what, what else did they do after the war? So it really was, it was difficult to find any sources. You know, this is back in the day when you had microfilm and microfiche for government documents and stuff. So, you know, I started with some of those traditional sources. You know, the Air Force Academy was very helpful getting me some microfilm on those official reports, which now the Air Force has all online that you know, which is very exciting and frustrating. I can still smell the microfilm printer, had a quarter a page that I you know, but yeah, so just a lot of those traditional government documents those briefings and because, you know, it's military history, they all did official reports at the end, right, those concluding reports. So all those statistics were kept. There was a medical report on the women, they had kept all these medical, you know, documents on them. But then yeah, oral histories was a huge part of it, because their story hadn't been told and asked, you know, nobody had asked. So in June of '96, is when I started my oral histories I interviewed Caro and her best friend Katherine Landry Steele, and Elaine Harmon and Ruth Carney, I think that weekend I interviewed eight women or something like that, just to fill in those gaps. And I, I had the good fortune of having a very good professor, Charles Johnson. He ran the Center for the Study of War and Society at the University of Tennessee. And he convinced me that I needed to do more than just interviews with the WASP about their years in the WASP, instead, do longitudinal oral histories. So I interviewed them about their lives before, their lives during the war, and then the post war years all the way to the present, depending on, you know, in the 90s, at the time I started, and so was able to get their entire life. And that's why in the book, I'm able to fill in those those spaces that that were missing from the documents. And, you know, they the WASP had just decided to start their archives at Texas Woman's University in 1993, the same year I met Carol. So I'm actually the first scholar to use the WASP archives. They have it written down. They didn't know me then. Now I work there in the as a history professor, which is very exciting. But but you know, they had one collection. Now they have an entire vault worth of boxes and documents and 10s of 1000s of photographs. But it was just building those sources out of out of nothing, which is exciting and frustrating at the same time. But I know that there are other scholars now who are already, you know, people working on their dissertation on different angles of the WASP story, are using the sources that I found, and encouraged the WASP to donate. So that's really, I don't know, that's really very rewarding as a scholar to know that you're doing more than just your own work, you're actually able to build sources for for future scholars. I'm not sure if that answered your question, in a roundabout way, but I used everything.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:42

Excellent. I love that. So talk to me a little bit about, this was a dissertation and presumably was written in a certain style to be a dissertation. But the book is not at all sort of the sort of academic style. It's, you know, through a trade publisher. And it's, it's very much a narrative like, like you're reading a novel. So can you talk some about that process of, of telling this story in that way?

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 18:07

Yeah, absolutely. And thank you for saying it was like a novel. That makes me feel good. Because it's really hard when you've been trained as an academic historian, and you're right, this was my dissertation initially, to shift gears and write in a narrative style. I think I one advantage I had is that one of the ways I helped support myself through graduate school was I wrote for different aviation magazines. And I wrote about the WASP. I wrote in Flight Journal, I wrote for Flight Training Magazine, I actually got to fly the Goodyear Blimp for an article I wrote for them. And I wrote about the WASP, there was a magazine called Woman Pilot at the time, and so I'd do kind of feature stories on some of the WASP. So I had some of that writing for that public audience experience. And I highly recommend it. I think it really makes you know what you know, right? Because you can talk to an academic audience, and you can talk about theories and other scholars and things. But you've got to really, it's almost that elevator speech, right? You've got to have that down pat to be able to get that story out to a public audience. I think the the shift to the narrative is being able to take a step back and find the story within your work right and and I'm very proud of the fact that this book is every bit as academic and scholarly as my dissertation was, moreso I think; and I followed the rule of three with my academic rules, right, you know, every every fact that's in there. It's it's the rule of three. I was corroborated all the way around. So it's just as accurate. I've got a lot of endnotes in the back. My editor I think I cheated a lot when we were editing and picked things up that were I was supposed to cut and put them in the back. So if you read it, the notes are very gossipy, and very good. But it's finding that story, where's that through line in in the work that you have, and recognizing that people have to be at the center of your work. And for that I took, you know, this big story of 1100 women and found five lead, you know, characters, I'm using quotation marks here, you know, who are real and all of whom I knew, personally, and all of whom, all five of them can go, well, it ended up being three that I started with five, and then in the book, that's three, and I ended up, you can take them all the way from the 1930s, through the war years, into the post war all the way through to, you know, 2016, for one of them. And I had to choose women that could tell the bigger WASP story, you know, and and so, you know, Teresa tells the story of the early women pilots and and, you know, all the way through, and Dora tells a story of the expansion of the WASP program. And Marty tells the story of those who came to it late and were in the last class and what happened; and then they were all active in the militarization efforts, or veterans efforts in the 1970s. So it's just finding that story, I think being true to your sources, but but kind of relaxing your brain a little to see the story that's there, you know what I mean? It's because it's because it's there, you just have to get out of your own way sometimes to find it.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:40

So you're a pilot, too. Can you talk some about cuz you talk, you write really eloquently about the actual experience of piloting these planes and what's that like? Can you talk about what that would have been like for them, you know, doing tons of different kinds of planes that they had to learn to fly, and sometimes being among the first to fly these planes, like what that experience would have been?

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 22:01

Yeah, yeah, absolutely. And I think I did have a real advantage, being a pilot myself. It was always funny when I did the oral histories, that once they found out I was a pilot, the whole tone changed. The whole language changed, and the way they described the flying changed, because it really was such a wonderful experience for them. And to get to, you know, they all came of age in that Golden Age of Aviation, when which we forget, you know, we think about Amelia Earhart, but she dies. And so it ends up and all ends poorly. But the American people were so passionate about flying. And so these women all grew up with that. And then they, they get in those airplanes, and this idea of the freedom that you can feel, because it's, it's not like climbing in the back of a airline today, right? That's not free; that's annoying. But to be up front is a lot more fun. And these small planes, you really, it gives you power, I think, to have that sense of strength that you can take off that plane, and you can land it and you know, you're in the air above, and you can see the world and get a whole new perspective. And then for the women to you know, to have the opportunity to fly those planes. I mean, those were the best planes of the day, the fastest, the heaviest, the strongest, that nobody would ever get a chance to fly again, you know, so few people and they knew what a privilege it was, and what an opportunity it was. And you know, most pilots you, you want to go higher and faster, and you know, just the opportunity for them to get in those planes. And if you read their letters, you know, they they talk about getting into the Stearman which is the open cockpit plane and how cold it was or how hot it was, or how wonderful it was. And then they get into the AT-6, which is much heavier and faster, and how nerve racking it was, but then they did it, you know. So it's really that I think airplanes are one of those things that you really can gain confidence in all aspects of life by like, you know, partnering with that aircraft, right, becoming one with the machine. It's just a really incredible feeling.

Kelly Therese Pollock 24:26

I think one of my favorite things was the army using women to show the men that they shouldn't be scared of certain planes.

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 24:35

Yep, they did that more than once. You know, it's so easy to fly, even a girl can do it. Right. And that that grew out of the 30s. You know, let's sell personal airplanes, and we'll have the women be the salespeople because then, you know, everybody knows that, that it's easy to fly, right? Yeah, they have the most sophisticated plane that you know, the B 29, that's incredibly dangerous and powerful plane and here, let's put two little girls in it and see see how the boys feel about that?

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:05

Yeah, gosh,well, and speaking of danger, there were women who died in the course of this. So the army, you know, as you write about didn't consider them to be military, they were civilian. And yet this was a really dangerous thing that they were doing. Can you talk some about what like the the response that the women, you know, as you talk to them, like, what, what they saw their role as in the war? And and how they sort of accepted that, that danger of what they were doing?

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 25:36

Yeah, yeah. And I think that's important, I think, you know, they all knew it was dangerous. They, none of them wanted to die. And I think that's, but aviation is dangerous, or just as, as any any sport of that level is. And, you know, you, you go into a flight, and you take as many precautions as you can, and you take it seriously. But you know that bad things happen sometimes. So they knew that there were risks, but they really did believe that they were doing something important for the war. And, you know, several of them talked about, you know, I couldn't knit, so I flew airplanes instead. And, you know, there was one Vi Cowden, who was, you know, was gonna join the Marines or join the Navy, and she liked the Navy's hats better, so probably the Navy, but then this chance to fly airplanes, which she'd always loved, opened up, and, you know, oh, yeah, if I'm going to volunteer for the war effort, that's the one I choose. And a lot of them felt that way, they felt very strongly about doing their part for the war effort. And, you know, if I'm going to do my part for the war effort, why not do it flying airplanes, cuz they really found that opportunity. Some of them their, their parents, you know, you know, usually one parent supported them, some were certain they were gonna go off and get killed. But, you know, it was, I think, one important thing to know about these women, and I didn't quite get it when I started, because when I started, I was their age, I was in my early 20s. And now I am no longer in my early 20s, we'll just say that. You guys do the math. But but they were so young. They were so young, the oldest was 35. But the average age was 22. Right? They were 18 and a half to 24 was was really the range there that most of them were. That is incredibly young, and you have a different kind of confidence when you're young like that, than you do when you're older, and you're willing to take more risks, and, you know, see the risk reward ratio in a different way than when you're when you're older. And a lot of them felt that way.

Kelly Therese Pollock 27:56

Yeah. So I think one of the interesting things about this story is how these women are very much products of their time. And yet it's pushing against sort of the expected of what a woman would do, then, you know, and I think the contrast of Nancy and Jacqueline is very sort of illustrative of that. Can you talk some about that? You know, it's such an interesting, like, some of them are really are like, Okay, this is what women do, you know, we're gonna go back after the war and get married and have kids and stuff. But they're sort of always pushing against that, you know, what's what's expected of women?

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 28:34

Mm hmm. Yeah. And I think so the most common trait of all these women is they were all very intelligent, right? You had to be you had to be well educated and, and quite smart to make it through this program. Right. Some of the some of the trainees who were very good pilots, they just didn't learn quickly enough. That's what a lot of the graduates say. And and so intelligence, and hard work were definite traits. But independence. You know, that's, that's a trait, you know, you talk to their kids today. And they're like, "Oh, Mom was so independent." And, you know, and they just were independent thinkers, and they were going to do what they were going to do. And I think that, that fit their mindset. Remember, these are women who grew up knowing they could vote, and they're really that first generation, you know, many of them were born in 1920, or right, you know, on either side of it. And so, you know, that, that growing up with a different attitude about well, of course, women can do things, right, this is the, you know, we're going to vote we're going to do all these things, and they really do push the limits of what women could do. And they didn't do it because they were women. You know, that's one of the things that I've talked to a lot of them about was you know, are you a feminist or did you do it, you know, for women's, you know, women's lib or and they're like, "Oh, God, no, oh, no, no, absolutely not. We just, I just did what I wanted to do. And if somebody said No, I said, Yes, I can. And so I did it." So is that more of an independent, you know, stubbornness and determination to do what they wanted to do than it was a broader I'm doing this for all womankind. You know, some of them were conscious of that. It depended on the individual; but but for the most part, it was, "Hey, well, I'm going to go and do this. And hopefully other women can do it too, because we are proving that we can." But but they were just very stubborn.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:41

Yeah, and, you know, I think this, this tension between, we need the women, we need them to be doing these important jobs, but only if it's not taking a job away from a man like as long as it's freeing up men to go overseas and fight then great, let's have the women do it. But the second it's taking a job away from a man, it's suddenly problematic. Yeah, you know, I guess if you could talk a little bit about that, that sort of push for militarization? That's a hard word to say. And, you know, what, what that looked like, and why it ultimately failed in the 40s?

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 31:17

Mm hmm. Yeah. So you know, the women were brought in, it's so complicated. And a whole book could be written just on this piece. I tried, but my editor made me cut a lot out. But, you know, this idea of the women were brought in, initially, as civilians, as many men were, you know, with the idea that after 90 days, they'd be made second lieutenants, and part of the Army Air Forces. But it's, that step kind of got stalled, because there was an effort to keep the women segregated and make them independent. And so they were going to bring them into the Women's Army Corps. And that didn't work because the Women's Army Corps couldn't have children. And a lot of the WASP did, you know, lots of lots of complicated reasons. So they were going to do it independently. They were going to make the women Air Force Service Pilots a part of the, you know, an independent group, militarized it just as they had women surgeons, right. They had, they had done this to other groups of women. But yeah, by the time the bill finally, actually got some momentum, it was 1944. And the Army Air Forces had stopped using civilian men pilots, who'd been training, you know, getting some initial flight training for men. It stopped using them. And the, you know, the men looked around and said, "Well, we'll do their job, you know, you can't have a bunch of women doing jobs that men can do." And that was that was the key of the whole thing is the women were there to release men, for other duties, not replace them. So you have in 1944, you have all these civilian flight instructors that are free, you have all these men that are coming back from the war that are still in the Army Air Forces and still need to fly. But they're, you know, they've served enough combat time. And so the idea was, well, you know, women are replacing the men, we can't have that. So the vote comes up in June of 1944, the last day of the session, very rushed, and it was after D Day, and at the point when everybody thought we were going to win the war by Christmas, and why would we bring all these women in that that, you know, are going to cost us all this money, and we've got enough men to replace them. So it was, was one of those things that the women didn't have the insurance that they needed, they didn't have get any of the postwar benefits. And if they, you know, they lost by 17 votes or something. If they had, if they had just been brought in, they could have gotten the medical care that they needed. Some of them who had, you know, hearing trouble and all sorts of, you know, people who've been in a crash, but survived, didn't get any any postwar help, you know. It was just really unfortunate, and I would argue unfair.

Kelly Therese Pollock 34:20

Yeah. And then the perhaps the most surprising part of the whole story is that when they are later fighting to get veteran status, Barry Goldwater becomes their champion. When I got to that point, I was like, wait,what?

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 34:34

Right. I appreciate that, because not everybody gets that right. Not everybody gets how crazy it is that Barry Goldwater's their helper. So, so yeah, in the 1970s, you know, late 1960s and into the 1970s, the women are like, "Wait a minute. We've been forgotten. The young women are fighting and we need to be recognized." And there were a number of reasons they they wanted to be recognized. The flag on their coffin was one of them. But yeah, they looked around for allies and they got Bruce Arnold on board, who was General Arnold's son. He used to tell the story that he, you know, was at a party with them, and after a series of martinis he agreed to help. They talked him into it. But yeah, then they got Barry Goldwater, Senator Barry Goldwater, who was one of two senators who voted against the Equal Rights Amendment to you know, the father of modern conservatism all these things. And, and, but he was their biggest advocate. And he, he fought with them for several years. And then he's the one that tacked the bill on, tacked the WASP on to, you know, all these bills until something got passed, with them a part of it. It was because he had flown with them. He flew with the Ferry Command during World War II. And so he had flown alongside some of these women pilots. It's like, well, if I'm a veteran, they're veterans, they, we did the same work. So he really was obviously a much more complicated figure than he's portrayed quite often. But he was just a huge advocate of these women pilots. And many argue it just simply wouldn't have happened without him. And I think I think they're probably right.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:19

Yeah. Well, I could probably keep asking you questions all day. But let's tell people how to get your book so they can read the story.

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 36:28

Oh, sure. That's nice too. My editor would be very pleased. So yeah, I mean, you can you can find it basically anywhere books are sold. It's I think it's on paperback, hardback, audiobook, ebook. However you however you like your books, it's available. And, and I do have a website, Katherine Sharp Landdeck.com that has some tidbits and things like that as well. So

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:53

And I'm, as any listener of this podcast knows, I love audiobooks. And this is a great audio book, so...

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 36:58

Oh, good. Yeah, they did a really good job with it and very professionally done. They called me a dozen times, while while they were recording, how do we pronounce this? What did they say, you know, and it was just very impressive, the whole process. And so I'm glad to hear that feedback that an audio listener loves the audiobook, because they were really great to work with.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:19

Yeah, definitely. Is there anything else you want to make sure we talk about?

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 37:23

Oh, I think you know, the WASP. I always ended my oral histories with them, and said, "Okay, well, what do you what do you want to walk away with? What do you want people to remember about you?" And almost every single one of them would sit up kind of straight and say, "We were first." And they were very adamant about that. And, and then they'd go on about oh, don't forget the 38th. And don't forget, but they were really proud of the fact that they were first and that they did what their country needed them to do. And so I think that's, that's maybe the thing to walk away with is they were first.

Kelly Therese Pollock 38:03

Yeah. Well, Kate, thank you so much. This was just a terrifically fun story to dig into, and I really appreciate learning more about them.

Dr. Katherine Sharp Landdeck 38:14

Well, thanks so much for reaching out, and I appreciate you helping me share their story.

Teddy 38:19

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode at UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History. Or on Facebook at Unsung History Podcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Katherine Sharp Landdeck

Katherine Sharp Landdeck is an associate professor of history at Texas Woman’s University, the home of the WASP archives. A Guggenheim Fellow at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and a graduate of the University of Tennessee, where she was a Normandy Scholar and earned her Ph.D. in American History, Landdeck has received numerous awards for her work on the WASP and has appeared as an expert on NPR’s Morning Edition, PBS, and the History channel. Her work has been published in The Washington Post, The Atlantic, and Time, as well as in numerous academic and aviation publications. Landdeck is a licensed pilot who flies whenever she can.