Quilting & the New Deal

As part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), so-called “unskilled” women were put to work in over 10,000 sewing rooms across the country, producing both garments and home goods for people in need. Those home goods included quilts, sometimes quickly-made utilitarian bedcoverings, but also artistic quilts worthy of exhibition. Quilts were featured in other New Deal Projects, too, like the WPA Handicraft Projects, part of the Women’s and Professional Projects Division. Throughout the Great Depression, the programs of the New Deal created a supportive and innovative environment for the art of quiltmaking.

Joining me in this episode is historian, writer, and podcaster Dr. Janneken Smucker, Professor of History at West Chester University and author of A New Deal for Quilts.

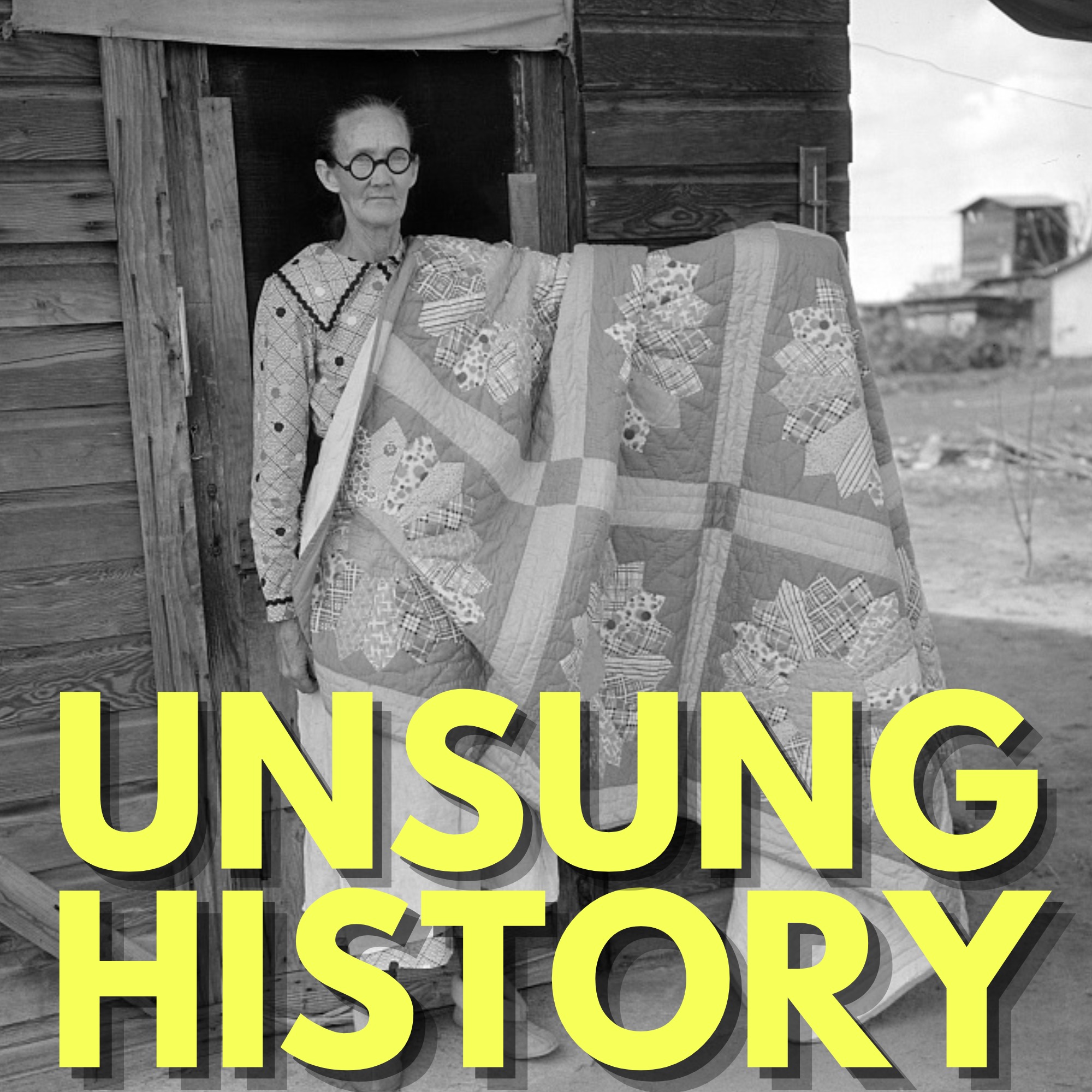

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “A Mazurka played on harmonica,” performed by Aaron Morgan and recorded as part of a WPA project by Sidney Robertson Cowell on July 17, 1939, in Northern California; the recording is available via the Library of Congress.The episode image is “Grandmother from Oklahoma and her pieced quilt. California, Kern County,” take by Dorothea Lange in February 1936 through the U.S. Farm Security Administration; the photograph is in the public domain and is available via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

Additional Sources:

- “The Works Progress Administration,” PBS American Experience.

- “Works Progress Administration (WPA),” History.com, Originally posted July 13, 2017, and updated September 21, 2022.

- “Question 22: 1940 Census Provides a Glimpse of the Demographics of the New Deal,” by Ashley Mattingly, Prologue Magazine, National Archives, Summer 2012, Vol. 44, No. 2.

- “Women and the New Deal,” Living New Deal.

- “Women’s Work Relief in the Great Depression,” by Martha H. Swain, History Now, February 2004

- “WPA sewing project kept Hoosier women working through the Great Depression,” by Dawn Mitchell, Indy Star, January 19, 2018.

- “‘We Patch Anything’: WPA Sewing Rooms in Fort Worth, Texas,” Living New Deal, May 27, 2013.

- “Frugal and Fashionable: Quiltmaking During the Great Depression,” The Quilt Index.

- “WPA Milwaukee Handicraft Project,” Milwaukee Public Museum.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

Kelly 0:38

In 1935, the unemployment rate in the United States was 20%, not quite what it had been at its peak in 1933, but still an astonishing figure. For comparison, in May, 2024, the unemployment rate was just 4%. It was in the context of 20% unemployment, that President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Works Progress Administration, which was designed to put those unemployed Americans to work. A few years later, over 3.3 million Americans, or about 2.4% of the total population of the country, worked for the WPA. Many of the employees of the WPA worked on public infrastructure projects, building over 4000 schools and 130 hospitals, planting 24 million trees, repairing over 280,000 miles of road, and constructing massive feats of engineering like the Hoover Dam. Eligibility for WPA employment was limited to unemployed US citizens aged 18 or older, who were certified as being in need. Employment was not limited to men, but the WPA would not employ more than one person in a household at a time, so as not to take away a job from another head of household who may need it. In practice, this meant that many fewer women than men worked for the WPA. At the peak of the WPA in 1938, 13.5% of WPA employees were women. Women with specific skill sets were employed by Federal One projects in art, music, theater, and writing, or were hired to do clerical jobs or work in libraries. But women were not put to work on construction projects. Instead of infrastructure projects, they were put to work sewing, weaving and knitting. As one WPA administrator put it, "For unskilled women, we have only the needle." In 1938, work in sewing rooms made up about 5% of all WPA jobs. At that time, there were 10,259 such sewing rooms across the country. If the workers did not already know how to sew, they were taught. Despite the federal administration of the sewing rooms, it was local supervisors who decided what was produced. In the Fort Worth, Texas sewing room, which opened in 1935, for example, workers both repaired clothing and sewed new garments. They liked to say that the initials WPA stood for "We Patch Anything." The over 2.3 million garments they produced included a "not to be sold" label. Instead, they were dispersed to people who needed them in Tarrant County, including sometimes the women in the sewing rooms themselves. By 1940, 650 women aged 35 to 64 worked there. When First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the Indianapolis sewing room, housed in the former RCA building, on June 17, 1936, there were 900 women at work, cutting, sewing and weaving. They presented Roosevelt with a quilt in honor of her visit. Quilts were not typically a primary product of most of the sewing rooms, but some sewing rooms did produce quilts, sometimes from fabric leftover from garment production, or recovered from clothing that was past the point of renovation. Articles on the Woodside Queens sewing room noted that workers there produced 127,000 quilts in a year, noting that, "The quilts have a filler of half wool and half cotton. They're made in the old fashioned way, tied with wool knots in nine inch squares, with two rows of stitching on the outer border." Although many of the quilts sewn in these sewing rooms were likely utilitarian bed coverings designed to be produced quickly, women in certain sewing rooms did create more artistic quilts, some of which were displayed as part of the WPA efforts of self promotion, in hopes that politicians and taxpayers would see value in the project. A report out of the Niagara Falls, New York sewing, room which employed only African American workers discussed, "A few of the women specially qualified," were making beautiful quilts that may be used in exhibitions, noting, "The design on the quilts is on the whole excellent and very artistic." It wasn't just in the sewing rooms that quilts were produced. In the WPA Handicraft Projects, part of the Women's and Professional Projects division, the goal was to, "revive handicraft that is being forgotten in a commercial age, and to train talented workers to create markets for their work." The best known of these handicraft projects was located in Milwaukee, but by 1938, 35,000 workers across 43 states were involved in the projects. The Milwaukee Handicraft Project, MHP, even boasted a 75 person quilt department, which offered at least 25 quilt designs, which were commissioned by local schools and hospitals. Unlike the quickly made utilitarian quilts commonly produced in sewing rooms, some of the MHP applique designs were quite intricate and tricky to sew. MHP's crafts, including quilts, were so in demand that they were shipped to all 48 states. Many of the workers in the MHP were immigrants working side by side with African American women. MHP's administrators paternalistically saw the project as changing the lives of the workers, not just in the short term by providing employment, but also in the longer term by exposing lower class women to culture. As the project director later recalled, workers, "learned so many things that they could use that they had never had an opportunity to because they were just indigent people." Unlike the administrators, the employees didn't keep records of their involvement. So we don't know if they were grateful for what the director saw as exposure to culture, or if they were just happy for a paycheck. Either way, projects like the MHP supported the art of quiltmaking during the Great Depression. Joining me now is historian, writer, and podcaster, Dr. Janneken Smucker, Professor of History at West Chester University, and the author of, "A New Deal for Quilts."

Kelly 9:14

Hi, Janneken. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Janneken Smucker 9:29

My pleasure. Thanks, Kelly for the invitation.

Kelly 9:31

Yes. So, I want to hear how you got started on being a quilt historian, not a thing that I realized many years ago existed and is just the coolest thing ever. So tell me how you got started.

Dr. Janneken Smucker 9:41

Sure thing. I grew up in northern Indiana in a Mennonite family, a modern Mennonite family, meaning we had cars and electricity and dressed like members of mainstream society and believed in higher education. However, I did, as part of that, hail from a many generations of quilt makers. I'm at least a fifth generation quilt maker. And when I was around age 16, I decided to make my first quilt. My mother had made one quilt at that point in her life, but my grandmother was prolific. And so I pulled a book off the shelf, like "How to Make a Sampler Quilt." A sampler is a quilt style with which each block has a different pattern. And I was hooked and loved picking out the fabric and the patterns and all the work in that that first quilt. I learned a lot from my grandmother and, and my mom. We set up my great grandmother's quilting frame in the dining room and all stitched on it to complete it. And I kept making quilts when I went to college, even set up a quilting frame in my college house my senior year and taught friends how to how to make quilt or how to how to actually do the tiny little quilting stitches. And then when they would leave, I would pull out their stitches because I have such high standards. But anyway, meanwhile, in studying history and Women's Studies, not even understanding that all of this is part and parcel, and it wasn't until a couple years later that I realized I didn't know one can be a quilt historian either. And I heard about a program in textile history that had a focus on quilts at the University of Nebraska Lincoln. I thought, "That's so ridiculous. Why would anyone study such a narrow subject?" But I kept thinking about it and kept thinking about it and ended up applying. And that's sort of how I started. I worked as the curatorial assistant, it's now called the International Quilt Museum at the University of Nebraska, and learned all about textile connoisseurship, and how to identify different patterns and geographic differences in quilts, and all sorts of things. And eventually then went on for my my doctorate in American history and kept kept studying quilts. But it really stemmed from that sort of hands on experience as a crafter, really, and then learning that I could combine my cultural heritage, my own passion for making quilts with my expertise as a historian.

Kelly 12:24

I love it. So this this project that we're going to talk about today about the New Deal and quilts, I want to hear a little bit about the sources that you have for this. I mean, one of the best parts about the New Deal, of course, is that it documented itself. And so, you know, what, what do we have? We've got some, I take it, material history, some quilts themselves, some photography, lots of documentation. So what are the sources that you're able to pull together then for this?

Dr. Janneken Smucker 12:51

The nugget of this project really started with the photography. Anytime I was working on some quilt related project, and I needed an old timey woman with a quilt, I could find one in the Farm Security Administration's photo archive, which was an enormous undertaking of at 10s of 1000s, if not hundreds of 1000s of photographs taken by professional photographers, who were tasked with documenting the lives of Americans during the Great Depression with a real focus on the migrants and tenant farmers, but also small town America. And I started to realize, well, there's so many of these photographs that document women making quilts or posed with quilts or quilts in homes. There's something to it. And I knew enough about the Farm Security Administration project that they're essentially these are, in some ways propaganda in that they are government created works that are trying to communicate a message. I'm not using propaganda in a pejorative term. I'm just using it as a government created communication strategy. So I started with the photographs and I as I continued to look in the archive, which is all handily digitized by the Library of Congress and available through their database, I saw more and more photographs of quilts. And I started to become clever with my search terms to find quilts even when they weren't like the focal subject of a photograph. So I started there and thought kind of, oh, maybe this will just be a small project about these photos. And then I soon realized that quilts were appearing in lots of other documentary sources from from the New Deal as well, including records of the Works Progress Administration, which operated sewing rooms and handicraft projects. There was so much, to your point about the New Deal documenting itself, reports. The 1920s and 30s and 40s are when bureaucracy really becomes a primary feature of American society. And there are reports on like every agency, every initiative, every project, and some of this is like number crunching, boring reports. But some of them also, amazingly describe, this quilt has three bunnies on it. Like, wow, someone took the time to to write this down in the 1930s. I also used quite a few extant physical quilts, which I was surprised as I began to undertake the project, I wasn't sure if there would be existing quilts that we could fully document as being made in some of these, whether they're WPA sewing rooms, or the Tennessee Valley Authority had an auxilary group that made quilts, whether we would be able to actually find the physical objects. In many cases we did, sometimes, I had to rely on photographs of of these objects. Keep in mind, I was working in earnest on this project beginning in spring of 2020, in my first and only so far sabbatical from my university appointment. And I had external grant money, I was gonna go do archival research and visit museums. And soon, of course, by March, I knew I wasn't going anywhere. So I really needed to rely on digitized sources, and generous and friendly archivists who were willing to go into their offices and send me copies of things and also really generous mentors, women much older than myself, who have been studying quilts for for decades. And I receive boxes in the mail or typed up notes from email of these real experts on American quiltmaking, who generously shared shared with me their resources, knowing that I didn't have access to things in the same way. The digitized sources, however, were really remarkable, because all government created documents, objects and photographs are in the public domain, because they're taxpayer created. Those are often the low hanging fruit for archives and libraries to digitize because they don't have to deal with any copyright issues when they are posting them in digital formats on on the internet. So I was amazed that I could find reports or the catalog that the Farm Security Administration published that advertised their sewing machine that they would allow families to buy on low interest loans. So it was kind of astounding, the weird sources that were available through places like HathiTrust, the National Archives, Library of Congress, Internet Archive, all sorts of hidden gems out there for those of you who like to surf online.

Kelly 17:59

So I'd love to talk a little bit about the idea of skilled and unskilled labor. So there are times as you're talking about these federal agencies, these things they're setting up for, you know, people who are out of work, need work, that sort of thing. And you know, at one point, I think someone says, for women who are unskilled, all we have is the needle and the idea of making a quilt as being unskilled. For anyone who's tried to make a quilt, kind of mind boggling. So could you talk a little bit about that? Like, what what is the purpose of some of these programs? And how are they thinking about labor? And who's doing what and what what women's work looks like?

Dr. Janneken Smucker 18:42

Yeah sure, and I really tried to be conscientious about using those air quotes around the term unskilled, because you're absolutely right. The skills that women who may have been limited education, may have been illiterate, may have been immigrants who didn't speak English, may have been people who moved north as part of the Great Migration and didn't have access to education, these are the unskilled, the so called unskilled. However, that is really because they were at the kind of the bottom of the totem pole. The Works Progress Administration, which was the primary wing that was a make work project, and that they their purpose was to give people a paycheck, in order to then of course, stimulate the economy, but also the side benefit is that projects that were needed for the good of the country could be worked on. So think of the dams and the roads and the community centers and schools that were built. That I guess is skilled labor in that it's construction. Although, to be fair, some of those men also were probably learning on the job. There was sort of a side benefit of some of the Works Progress Administration programs in that they provided vocational training. And that was part of the expectation and outcome as well. So women who were working for the WPA sewing rooms may not have brought their own skills to the job, meaning they might not have known how to operate an industrial sewing machine. And the idea was that they would learn how and then they could transfer that skill to for profit industry, so they could transition out of the so called dole of the the WPA was providing and work in factories. That really didn't happen as much as they had hoped it would with the WPA, in particular for women. And in large part, that's because the women who are able and allowed to have the jobs in the WPA, you had to be the head of household, meaning you had no father or husband, who was providing for you. That's how you could qualify for a WPA job as a woman. So that already is like limiting the pool of potential workers. And often, those are women who are widows or older women who don't have anyone else around that can care for them financially. So some of it is that they're unskilled and that they haven't worked outside the home prior, which was typical for the early 20th century. Of course, women weren't working in large numbers at that point in time. But this this idea of of unskilled, really jarred at me as well was any woman who was taking care of a household in whatever capacity even if it's as a daughter, as a mother, as a wife, you have a lot of skills that are required in the course of of life, and maybe not every woman was adept at sewing. And there were a you know, I have evidence, you know, letters and reports that indicate, "I've never used a needle and thread before and now I can make my family's clothing." So those are the kinds of testimonials you sometimes hear that like they did empower women with with new new skills that they might not have had. It is kind of this transitional era for clothing in particular, that there is ready to wear clothing that can easily be purchased. However, it might have been out of reach and too expensive, particularly during the Great Depression. And then we're sort of in between the the production economy of the 19th century and the consumer economy that really emerges in the 20th century so many women are kind of in between. They might have some sewing skills, but not have used fancy sewing machine.

Kelly 22:49

Could you talk some about the kinds of designs that we see in quilts from this New Deal era? And you know, you talk in the book about how there's a colonial revival, kind of a faux colonial revival that's going on, not necessarily based in reality. But what sorts of things we see both in terms of the kinds of quilts, the colors that we see in in quilts that are coming out at this time?

Dr. Janneken Smucker 23:16

Quilt making was very popular during the 1930s. And and that is in part because of this so called colonial revival. Quilts really take off as a domestic home production craft in the 19th century, in large numbers following the industrial revolution. So by the time the 1930s are around, quilt making has kind of ebbed and flowed multiple times and is sort of falling out of fashion and then really reemerging in the 20s and 30s as a popular home craft. And there were many commercially available quilt patterns at that time, whether they were available through mail order companies, every small town newspaper, every major city newspaper had a quilt column published. They were often syndicated, although some newspapers had their own like kind of celebrity quilt maker. So these patterns would be published. And then women who were interested in making quilts could either just send in 10 cents or a stamp to get the pattern sent to you in the mail. Or if you were clever, you could see the little reproduction that was printed in the newspaper and and crib a pattern from it. So these popular designs of the 1930s were really emphasize scrappiness and thrift on one part, as a way of sort of making do during the Great Depression. The the thrifty, scrappy, look became popular and frugalness became fashionable as part of the Great Depression. So we see lots of patterns that make great use of lots of small bits and pieces of fabric. That also ties back to the colonial revival because there's this sort of false belief that all quilts are built or created out of a need and salvage and that they're recycled from other fabrics. And that really is not true, particularly prior to the Industrial Revolution, textiles were the most expensive thing a house would own. So that weren't necessarily something that you would cut up your textiles in order to sew them back together again. And then following the Industrial Revolution, textiles became abundant and fairly cheap. So then quiltmaking, as we know it, becomes a very popular pastime, and people are buying fabric specifically to cut it up to make quilts. And you could even buy the late 19th century, buy bags of scraps to kind of create that scrappy look. You could order those from a lady's magazine. So some of this is all the swirling things in the 19th century prior to the Great Depression. But then in the Great Depression, there is a need to use up everything you have. So the salvage aspect of quiltmaking becomes a reality during the 1930s. And women are repurposing feed sacks and sugar sacks. These are cloth bags that are made as like dual use, dual use packaging essentially. And the manufacturers of these sacks start to realize that women want the pretty ones. So they cater to them and print you know, little Calico designs on the on the fabric bags that women then reuse in their quilts and their clothing and so forth. There's another wing of quiltmaking that is is very much inspired by the designs of the 19th century. And these are much more ornate applique quilts often using very cheerful pastel colors. Pastels are really in vogue during the Great Depression years, both in clothing, women's clothing, and as well as in quilts. So that means like, there's this particular shade of green called Nile green or apple green that is like quintessentially of the Great Depression era and the powder blue and the Easter egg colors of yellows and pinks and oranges are all really ubiquitous. They're not bold colors. They're the the soft pastel colors are very common.

Kelly 23:25

Quilting, of course, is not just something that white women do. And you talk about how there is also quilting happening in African American communities. There is of course, as may not be surprising to people, some patronizing attitudes about you know, like white women coming into African American communities and saying like, this is how you homemake and you know these sorts of things. But you do say in the book that you can't tell just by looking at a quilt the race of the person who made it. So can you talk a little bit about what what racial dynamics look like in this these WPA activities and the Tennessee Valley Authority and you know what, what this looks like, but then at the end of the day, like quilts are quilts.

Dr. Janneken Smucker 28:15

Right. I very much adhere to this standard that you cannot tell the race of a quilt maker by looking at a quilt. Particularly in recent decades, there have been efforts to do so by by claiming that very improvisational haphazard quilts are typical of the African American production. The thing is, we see those types of quilts often made in white enclaves. Generally, those very makeshift make do quilts that we characterize as improvisational are from more rural areas, many of them from the south. In the south, of course, during the 1930s, this is the Jim Crow era. So it's a very segregated experience. African Americans who were still living in the south are largely sharecroppers or tenant farmers. And the New Deal programs actually gave those populations a lot of attention because they were disproportionately suffering during the Great Depression. And while the federal government ostensibly said we provide these in an equitable fashion, they also catered to local custom, as they called it, which meant programs in the south were largely segregated. And this is true, for example, in the Tennessee Valley Authority. The TVA built dams on the Tennessee River to provide rural electrification but also to create recreational areas. And this also provided work, so these were government jobs. African Americans made up a lot of the population in the Tennessee Valley, but they disproportionately made up only few of the workers who were able to get employment in the TVA. There's a particular group of quilts that were made by, as part of this home beautification project that Ruth Clement Bond, who was an African American woman married to the most senior African American male staffer on the TVA. He was sort of in charge of hiring other African American workers in the region. And so she created this project for home beautification, which included making furniture out of the local willow trees that were available using the feed sacks that were available in the commissaries and the the villages where the construction workers lived. But she also designed quilts and distributed or quilt patterns and distributed those patterns among women in these various villages on the Tennessee River. These villages were segregated themselves. So one side of the river might have the white half of the village with more permanent structures, better recreation facilities, better dining hall, better schools, and then the other side of the river would house the African American workers, who were smaller in number. They couldn't participate in the same recreational activities as their white counterparts. So part of this beautification project, in addition to providing beauty, was to empower the African American women who were often the spouses of the male construction workers living there. That's an example of a particular, we know those quilts are made by African Americans because we have the oral histories to back it up, and the extant quilts as well. Other quilts that are these kinds of scrap quilts made of a feed sack, made of old denim work clothes, sometimes we speculate that they are made by African Americans without necessarily knowing one way or another, so much has been lost. Unfortunately, when quilts move out of homes, quilts are often not signed, the way a painting might be. And so this is also my PSA: label your quilts. Make a little cloth and write with a pen about whatever you know about the quilt, whether you made it yourself or received it as a gift or inherited it. Anyway, we have to do a lot of guesswork generally to figure out where a quilt was made, when it was made, by whom it was made. So I try in this particular project to use well documented quilts when they're available. But that, of course, is not always the case. As you mentioned, there were home economists, hired by the federal government, sometimes by the Farm Security Administration, sometimes by the Department of Agriculture. And they were sent out to give guidance to farm families. And there was a male equivalent, who was like that the agriculture specialists as well. And these women who were home economists, they were college educated, often even had master's degrees, and they're coming into communities telling them the right way to use a pressure cooker to cook your food, the right way to garden, about nutrition, and also about how to make things out of fabric, whether that's clothing and quilts, little decorative doilies to cover an end table, how to even make some furniture at home. There was a dynamic where sometimes these would be white women coming into an African American community or even a patronizing poor white community, but you have the educated white woman coming in to tell these uneducated rural women how to do things. And then of course, that dynamic became exacerbated when it was also based on race. There were some states that would not allow the intermixing of home economists with a population that was not of the same race. So for example, an African American Home Economist could not work with white clients. And in some cases, they lost there would not have a white home economist working with African American clients. Because of the strong emphasis on segregation in the Jim Crow south.

Kelly 34:24

One of the most delightful things is that people start sending quilts to the White House to Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. This is very hard to imagine now. I doubt it would even get to the president if I tried to send a quilt now. Could you talk a little bit about that and the reasons people were doing that?

Dr. Janneken Smucker 34:41

Sure, and absolutely, that the bureaucracy that we have today is even more strict about gift giving, of course, but gifts could in fact be sent to the White House back in the 1930s, and a remarkable outpouring of quilts were sent out as thank you gifts to the Roosevelts. Sometimes these would be very commemorative quilts. There were several well known, well documented instances of quilters who made National Recovery Act quilts. That's what's called the NRA at the time. This is a different NRA than we are familiar with today. But the NRA symbol was this Blue Eagle that was holding, the talons were holding a cog of industry. And this was a image that was affixed to manufactured products or, or hung in a window of a shop, if that manufacturer or store adhered to a set of labor and consumer practices that had been administered by the National Recovery Act in 1933. So there were particular NRA quilts and these are all grassroots. There's not a standardized pattern. Some of these we know were sent to the Roosevelts as thank you gifts. There were others that were just happened to be made in a WPA sewing room for example, or made by there was a set of sisters in California, they their last name was Romeo so they were referred to as the Romeo sisters. And they sent very, what I would say commonplace quilts of the 1930s like a grandmother's flower garden and double wedding ring quilts to Eleanor Roosevelt. Eleanor was known to be an appreciator of quilts and of crafts in general. She actually prior to the Roosevelt administration was a partner in a reproduction furniture company that made like colonial style furniture in New England. So she had a real interest in crafts. She had a really strong interest in weaving, but she has been referred to in several pieces of literature from the era as a as a quilt lover or a quilt collector, even. It's hard to know, we haven't found any evidence of a collection of quilts per se, although around a dozen quilts are in the collection of the FDR Library and Museum. And most of those were given in fact as gifts to the Roosevelts during the time period. But there was so much gratitude towards Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. They were really viewed as kind of the saviors of, of the American populace of those who were particularly struggling economically. So there was so much admiration. There's a letter in particular, I won't recall the exact words, where where the quiltmaker is just effusive about how much she is inspired by Eleanor in particular, and how grateful she is.

Kelly 37:48

There is so much more in your book that we're not going to get to and there are amazing pictures. So can you please tell listeners how they could get a copy?

Dr. Janneken Smucker 37:56

Well, absolutely. The book is called, "A New Deal for Quilts." It's available wherever you purchase books online, for sure. It's published by the University of Nebraska Press is the distributor the publisher is actually the International Quilt Museum, which is at the University of Nebraska. So easily putting that into any any search bar, you should be able to find it. Larger brick and mortar bookstores will also have copies of it available and any book bookseller could probably special order for you as well. It's it's got pretty wide distribution.

Kelly 38:29

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Janneken Smucker 38:34

Well, I'm going to just toot my own horn slightly in that on June 22, I will be at the FDR Library in Hyde Park, New York, giving a public talk as part of a larger event that includes receiving an award for the living New Deal Book Award of the year. I'm a co recipient of that award. And I can't tell you what an honor it was to hear that, as someone who studies this very niche subject, you know. I told you how I started making quilts as a teenager and like, eventually learned I could study this as my academic subject. But most historians are very uninterested in what I have to say about quilts. They view it as sort of this like, "Oh, that's not a real historical subject." So it's so gratifying that a national organization that focuses on the study and the preservation of the legacy of the New Deal, recognized this book as a as an important contribution to our New Deal history. So I'm really delighted that I'll be at the FDR Library and celebrating this award.

Kelly 39:47

Congratulations. That is very exciting, and I can't speak for other people, but I loved learning about this part of the New Deal. And anytime I can learn about anything craft history I think is just it's it's kind of it's the whole purpose of this podcast, right? It's like the it's the unsung stuff. It's the stuff that you know, people don't talk as much about it doesn't hit history books, but it's so important in the lives of people.

Dr. Janneken Smucker 40:13

Yeah. You epitomize what I'm saying is like, well, many historians or would disregard the subject. It is one of these important things of social and cultural history what the kinds of every day women in particular were engaged in and and I'm really happy to share that research with all your potential readers.

Kelly 40:38

Well, Janneken, thank you so much for speaking with me. This was so much fun to learn about.

Dr. Janneken Smucker 40:42

It's been my pleasure. Thanks Kelly.

Teddy 41:12

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode, and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Janneken Smucker, Professor of History at West Chester University, specializes in digital and public history and material culture. She also serves as the co-editor of the Oral History Review. In the classroom, she integrates technology and the humanities, working with students to create digital projects, including the award-winning Goin’ North: Stories from the First Great Migration to Philadelphia and Philadelphia Immigration. Janneken consults on digital projects for non-profits and museums and leads workshops on digital tools and strategies. She was the 2015 co-recipient of WCU’s E. Riley Holman Memorial Faculty Award for innovative teaching. She currently serves as WCU’s Faculty Associate for Teaching and Learning. Author of Amish Quilts: Crafting an American Icon (Johns Hopkins, 2013), Janneken lectures and writes about quilts for popular and academic audiences. Her 2023 book, A New Deal for Quilts, explores the ways the federal programs combating the Great Depression drew on quilts and quiltmaking as part of their relief and public relation efforts.