Marguerite Cartwright

Dr. Marguerite Phillips Dorsey Cartwright, born May 17, 1910, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was a journalist, sociologist, educator, and actress, who served as a correspondent for the United Nations, attended and wrote about both the Bandung Conference and the All-African People's Conference, and was appointed to the Provisional Council of the University of Nigeria, where she became one of five trustees. Joining me in this episode to discuss both Marguerite Cartwright and Black women’s leadership in the fight for human rights is Dr. Keisha N. Blain, Professor of History and Africana Studies at Brown University and author of Without Fear: Black Women and the Making of Human Rights.

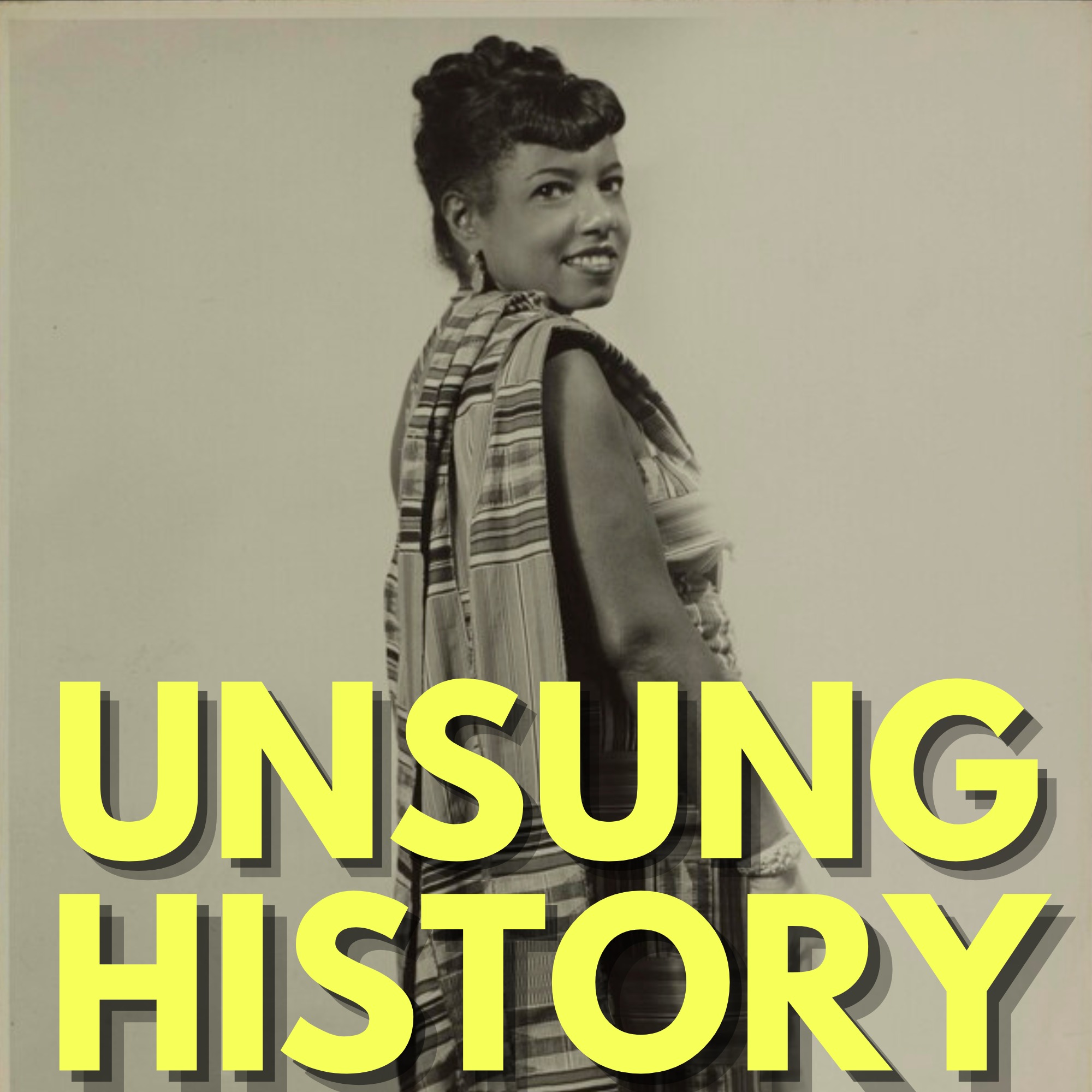

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode audio is “Down South blues,” written by Fletcher Henderson, Alberta Hunter, and Ethel Waters, and performed by The Virginians, in New York City, on September 25, 1923; the audio is available via the Library of Congress National Jukebox and is in the public domain. The episode image is “Portrait of Marguerite Cartwright wearing a dashiki, undated,” by John Schiff; the photograph is courtesy Leo Baeck Institute and is used under fair use guidelines.

Additional Sources:

- “Marguerite Cartwright and African-American Internationalism [video],” Society of Southwest Archivists, August 13, 2021.

- “M. P. CARTWRIGHT,” The New York Times, May 9, 1986, Section D, Page 22.

- “Introducing Marguerite Cartwright,” Amistad Research Center.

- “Cartwright, Marguerite, 1910-1986,” Biographical Note, Marguerite Cartwright papers, Amistad Research Center.

- “Bandung Conference (Asian-African Conference), 1955,” Office of the Historian, United States Department of State.

- “AAPC Background,” Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode, and please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. Marguerite Phillips Dorsey was born on May 17, 1910, the only child of Joseph A. and Mary Louise Ross Dorsey, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. A bright child, Marguerite finished high school at the age of 15, after which she enrolled in Boston University, earning both her bachelor's and master's degrees by the age of 19. Her master's thesis was on the African origins of drama. At Boston University, Marguerite met her future husband, Leonard Carl Cartwright, a white man who became a chemical engineer. Interracial marriage was legal in New York in December, 1930, when they wed. After briefly working as a school teacher, Cartwright turned to show business, dancing at the Cotton Club with Lena Horne, and appearing on Broadway in Paul Green's "Roll Sweet Chariot," and in six Hollywood films, including "The Green Pastures" in 1936, a film with an all Black cast that depicted stories from the Bible. In the 1930s, Cartwright worked in the Welfare Department in New York. She was not allowed to continue her work when she chose to campaign for FDR, so she enrolled in doctoral work at New York University, where in 1948, she earned her Doctorate of Education in Social Studies. Her dissertation focused on anti discrimination legislation, and she followed that with postdoctoral research at Columbia University and the New School for Social Research. In 1955 Cartwright began writing for the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the leading Black newspapers of the day, penning articles on national and global politics. A prolific writer, Cartwright didn't limit her contributions to the Courier, writing as well for the New York Amsterdam News, Negro History Bulletin, Phylon, and other publications. From 1955 to 1957, Cartwright wrote a weekly column called, "Around the United Nations." As a member of the UN Correspondence Association, Cartwright aimed to inform Black Americans about the work of the UN, and sought to convince them of the importance of paying attention to an organization that worked on, "such matters of universal concern as lasting peace, human rights, world reconstruction, food distribution, world wealth, the welfare of the world's children, world literacy, world trade and economy, conservation and others." Cartwright also traveled widely and wrote about global Black struggles. In 1955, she traveled to West Java, Indonesia to attend the Bandung Conference, where representatives from the governments of 29 Asian and African nations gathered. The conference resulted in a resolution outlining goals, including economic and cultural cooperation, protection of human rights, and an end to racial discrimination. As Cartwright wrote, "The conference at Bandung, introduced the people of Asia and Africa to international politics and made known to the world their determination to have their voices heard." Cartwright supported African self determination and criticized the UN for its 1956 article on self determination because it had not acted sooner to address apartheid. Throughout the 1950s, Cartwright traveled to Africa repeatedly, taking over 25 trips, interviewing leaders and lecturing at colleges in Liberia and Kenya. In 1957, Kwame Nkrumah, the first prime minister of independent Ghana, invited Cartwright to Ghana's independence celebrations. When the University of Nigeria was established with a grant of $14,000,000 and 10,000 acres from the Eastern Nigeria government, Nigerian president Nnamdi Azikiwe and the Eastern Nigeria Parliament appointed Cartwright to the university's Provisional Council. A street in Nsukka, Nigeria is named in Cartwright's honor. Cartwright was a special guest of Azikiwe at Nigeria's independence celebrations in 1960, and she was instrumental in ensuring that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. attended as well. That was only one of the times that Cartwright forged connections between Africans and African Americans. When Nigeria's minister of finance, Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh attended meetings at the UN in New York in 1958, Cartwright introduced him to the Black community in Harlem, for which he was very grateful. In December of 1958, Cartwright traveled to Accra, Ghana to attend the first All-African People's Conference. Over 300 people participated in the conference from the independent States of Africa, including Egypt, Ethiopia and Liberia, as well as from the then African territories like Angola, Cameroon, Kenya, Rhodesia and Uganda, and delegates from Canada, China, the UK, the United States, and other countries outside Africa. There, they discussed encouraging independence movements and unity within Africa. Cartwright described the conference as a place to talk about, "ideals of human dignity, mutual respect and the complete espousal of the objectives of the UN Charter and the Declaration of the Rights of Man." Activists, Shirley Dubois and Eslanda Robeson attended the conference as well. Cartwright belonged to a number of organizations throughout her life, including the National Council of Negro Women, the NAACP, the Harlem Fashion Institute, the American Wind Symphony Orchestra, the Peace Corps, the American Council on Race Relations, and the American Committee on Africa, along with professional organizations like the American Association of University Women and the Public Education Association. Marguerite Cartwright died in May, 1986, at the age of 76. Joining me in this episode to discuss both Marguerite Cartwright and Black women's leadership in the fight for human rights is Dr. Keisha N. Blain, Professor of History and Africana Studies at Brown University, and author of "Without Fear: Black Women and the Making of Human Rights."

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:40

Hi, Keisha, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Keisha N. Blain 9:49

Thanks for having me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:49

Yes, this is an incredible book, and I'm excited to talk to you about it. I want to start by asking just how you got started. You've written several other books, like, Why? Why this book? Why now?

Dr. Keisha N. Blain 9:57

Multiple reasons. I was in the process of finishing up a book on Fannie Lou Hamer, "Until I Am Free." And at the time, I was actually a fellow at the Carr Ryan Center for Human Rights Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. And one of the things that happened during my time there is that I spent a lot of time thinking about Fannie Lou Hamer as not only a civil rights activist and grappling with her significance as it relates to the expansion of Black voting rights, but I spent a lot of time thinking about her as a human rights activist and specifically grappling with the global dimensions of her political activism, which is an aspect that has not received as much attention in the scholarly literature. And I ended up writing a chapter about Hamer's internationalism in "Until I Am Free." But it was in that process of writing that particular chapter, as I was finishing up the manuscript, I thought it would be important to really think broadly about Black women's contributions to the struggle for human rights. And I think 2020 was a particular moment that emphasized the need for a book on this topic. And I'm specifically thinking about the political and social movement really rose to the surface in 2020 so many things happened. But one of the things that did happen was we saw a, I think, fierce national and global response to the police killing of George Floyd. And one of the particular characteristics of the movements that were taking place at the time is the prominence of Black women leaders. At the time, multiple journalists reached out to me to ask my thoughts on what it meant to see so many Black women in a very visible way, speaking, certainly to diverse audiences, speaking publicly about state sanctioned violence, thinking about a range of urgent topics and joint actions transnationally. So all of that was happening, and I was speaking constantly about what it meant to have these women in these roles. And for some people, it appeared that this was a new development, something that they had not seen before. But I knew, as someone who had written so much on Black women's history in both the national and global context, is that this was very much not new, but these women were certainly building on a rich history of Black women's political engagement. And I offered commentary in various spaces. I ended up writing a piece in "Foreign Affairs," in which I spoke specifically emphasize Black women's roles in the historical context. And as I was doing that, I thought, okay, I really have a lot more to say here, and it's important for me to write a book on this subject. So I set out to write a book in earnest in 2020, started pulling the pieces together, building on some material that I had collected even years before. Didn't quite know what to do with the material. I was able to return to many of these texts in this new book. So I think, in a nutshell, the political moment, developments taking place nationally and globally emphasize the need for a book that would capture the ways that Black women shaped human rights history.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:33

Let's talk, then, a little bit about what, what is human rights? You know? How is this distinct from civil rights, which people, of course, know a lot about the Civil Rights Movement. How are you defining human rights and what, what does that mean in the context of the Black women's leadership?

Dr. Keisha N. Blain 13:51

Yes, as we know, the term human rights means many things to different people. And then, of course, we understand that its meaning in so many ways, will shift across time and even across space, but in the broadest sense, what I emphasize in the book is that these women who I discuss saw human rights as essentially God given protections that they knew one they certainly made the case could not be taken away because they were divine inspired, and protections that were owed to them simply because they are humans and that it didn't really matter their citizenship status. It didn't even matter their location. At the end of the day, what these women wanted to emphasize is that there were some core values, and in the book, I draw on Lynn Hunt's work to emphasize three values that these women emphasize in their own writings and speeches. And that is, first, universal rights, that there are just certain protections that everyone should have everywhere, and equal rights that each individual should have equal access to things like quality education, quality healthcare, the playing field should be equal similarly, regardless of the location and regardless of one's race and one's gender. And then to the first point that I was making, natural rights, that these are rights that are inherent, rights that are specifically tied to one's humanity. And when you frame it that way, it's a very different kind of argument than, say, the kinds of arguments that, of course, someone like Fannie Lou Hamer made in 1964. She's talking about the importance of recognizing citizenship rights, of making the Black people have the right to cast a ballot because they are citizens of the United States, and she's emphasizing the Reconstruction amendments as just one example. All of these things certainly matter in the history. But part of what I'm doing in this book is saying that Black women were thinking beyond that, including Hamer herself, were thinking beyond that, and they were trying to make a larger claim in order to effectively shame the United States on a global scale, so that others would would understand that the lack of protection that Black people experience in the United States wasn't just about them being treated as second class citizens, and certainly that was part of it, but more to the point that they were not even being treated as humans. And so it emphasized the urgency of the demand, and then I think it spurred them to forge transnational networks and solidarities, because they understood the importance of drawing the connections between what's happening in the local level to what's happening nationally, to what's happening globally.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:08

A lot of studies of human rights, of course, look kind of top down at organizations and things that are are thinking about human rights, or they're looking at state actors. This, of course, is, is not that kind of study. Many of these women, by virtue of being Black women in the US in the 20th century or earlier, didn't have that kind of power. So what does it mean to look at this bottom up?

Dr. Keisha N. Blain 17:31

Yes, this is absolutely what I intended to do from the very beginning, because I felt a sense of frustration that the focus is often on those who hold official positions. So we certainly talk about diplomats, or we focus on key organizations like the United Nations, Amnesty International. And I'm not suggesting that we don't pay attention to that, but part of what I wanted to capture in this book was at the basic level and at the grassroots level, how did Black women in the United States take on human rights? So that's one question, and how did they effectively make it their own? So as people are using the term or talking about human rights on a global scale, how do Black women then take a hold of this idea and make and turn this concept into an active organizing principle? So in so many ways, I'm trying to capture what's happening within communities even moreso what's happening with people who don't have access? We talk a lot about this notion of having a seat at the table, and for many of the women who I am discussing in this book, they simply they don't have a seat at the table. They're not even in the room. They just don't have that access, that proximity, by virtue of their race, by virtue of gender, in different contexts. And yet it doesn't mean that they don't try to shape human rights discourse. It doesn't mean that they don't try to move things forward, not solely themselves, but for other marginalized groups. And so the book captures what that looks like. One of the things that's so fascinating about it is readers encounter, well, certainly women they have not heard of before, but they also, I think, get to see how an ordinary Black woman who may not have the resources or may not have the ability to be part of the more formal conversation, still assert their political power and still show that their voices are heard, and they do so through all these creative means. Just as a example, I talk about someone like Madam C. J. Walker, who, in fact, is a recognized figure, as you know, in the history. And one of the things that I emphasize in the book is the role that she played in the establishment of the International League for Darker Peoples, the ILDP, a short lived but very significant political organization that ultimately focuses on making the connections between the struggle for expanded rights for Black people in the US context, and connecting it to global struggles in different spaces. And one thing that Madam C.J. Walker does is she utilizes her her home at a practical level. She allows a group of activists to come into her home. That's what ILDP had, where they come together for their first meeting in 1919, and then she is giving financial resources to the group to be able to advance their mission. At one point, she helps to organize a meeting between ILDP members and Japanese delegates who are getting ready to attend the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. And then the purpose of that is to, in a way, use them, or attempt to use them as proxy, to stand in for the group and and broadly for for the the interests of African Americans. And certainly Madam C.J. Walker and others, they're they're trying to push forward this, this idea of racial equality. And they're trying to make sure that as people are thinking about peace in the broadest terms as they're thinking about stability, all of these ideas that they're that they're not overlooking the experiences and the real concerns of people of African descent. And so it's, it's, it's an attempt to to shape human rights history at a level that I don't think so many people pay attention to. They might pay attention to the Paris Peace Conference. So that's a critical moment. That's something we certainly know a lot about. But here you have an example of someone working behind the scenes. It seems like a small thing, but it's not. And I as I capture in the book, it really helps to build a kind of momentum as we move forward in the history, and you see how other women later would do similar kinds of things. So it is, as you say, a grassroots story in which we are able to think about what people are doing on the ground and how that connects to what is happening from the top.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:33

You open Chapter One with one of my very favorite historical actors, Ida B. Wells. Could you talk a little bit about Ida B. Wells and her anti-lynching campaigns and her journalism as a Human Rights Project?

Dr. Keisha N. Blain 17:33

Yes, I decided to open with Ida B. Wells because one of the things that captured my attention in the process of doing the research was how much she thought broadly about human rights, even without necessarily using the term, but still emphasizing the core values that that I point to thinking about universal rights, natural rights and equal rights. Ida B. Wells, as we know, spoke out very passionately against lynching that was taking place in the United States, and she called on the federal government, on various instances, called on the federal government to offer protection for Black people. She she spoke about citizenship rights to be sure. She spoke about the fact that Black people should expect the federal government to protect them, should, should, in fact, pass anti-lynching legislation, and should enforce this legislation. As we know, that was not happening in the 19th century, in the early 20th century. And one of the things that Ida B. Wells does in the late 19th century is she travels to the UK. And this particular trip is important because it provides a space for her to talk about lynching for an international audience. It provides a space for her to, in fact, broaden the argument, and and it's clear in her speeches, as it is clear in her writings during this period that she is making a claim that the problem with lynching isn't solely that it's in violation of citizenship rights, but but at the fundamental level, it is in fact a violation of human rights. It is in fact evidence of human rights abuses that are taking place. And and so she uses that as a way to to to shame the United States. She uses that as as a way to to get others outside the US to to recognize the problem that's taking place on US soil, and how it has broader implications. And I try to focus specifically on that, think, as a way to add some texture to the literature and the way we talk about her. And then the other thing that I do in that chapter is draw a connection between what Ida B. Wells is saying in the late 19th century, and what another Black woman, Maria Stewart, is saying several years earlier, in the 1830s out of Boston. So it is both an intellectual history in one sense, and then thinking through the dynamics of a social and political perspective that I think will help readers see how Ida B. Wells is, in fact, a key voice in early human rights history. We should know that. At the same time, I think the scholarship on human rights history has not given Ida B. Wells the the attention that she certainly deserves.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:33

People may have heard of Ida B. Wells, hopefully. She's got a Barbie doll. But another journalist that you talk about that I had never heard of, and I wish I had, because her story is so important, is that of Marguerite Cartwright. Can you talk a little bit about what Marguerite Cartwright is doing in her journalism, how she's thinking about the United Nations and connections with Africa?

Dr. Keisha N. Blain 17:33

Yes, Marguerite Cartwright is someone who I first learned about about 10 years ago, and have always been interested in writing about her. So it was wonderful to be able to have the chance to do that this particular project. As you know, she's a journalist. She's also a professor at the 1950s and 1960s. She's writing for primarily Black newspapers. She's a columnist for The Pittsburgh Courier, but also for New Amsterdam News. And I find her story so remarkable because what she does is she uses the the the the the avenue of journalism as a way to advance human rights advocacy. As just one example, she's traveling across the globe, and she's attending very significant gatherings in order to observe, to listen and report back to an American audience, specifically a Black American audience. So 1955, she attends the pivotal Bandung Conference, which we know as perhaps one of the most significant gatherings for Afro Asian political and social movements. And she goes to the gathering, and she returns to United States, writes about what she hears, what she sees, and then, in a way, translates all of that for Black Americans, to explain why it matters, why Bandung matters, and not solely in a general sense, but what it means for Black people in the US context. Her columns then provide a window for many readers, including, as you can imagine, those who simply did not have the privilege to be able to travel abroad. They now have a window into key historical developments that are taking place in real time, and they're able to make sense of the world in which they're living. And Marguerite Cartwright plays a role in that. The other thing that I talk about in detail is her attendance at the 1958 All-African People's Conference, which is held in Accra, Ghana, organized by Kwame Nkrumah and several other key African activists and intellectuals. And I emphasize how what it means for this Black woman to be in this space. One of the things that's very clear is that this is a male dominated space. There are a few women in attendance, but they're not playing any formal roles. They're not giving speeches. They're just not involved at the level of the men who are there. And it is very much reflective of the time period. We understand the kind of patriarchal structure that is evident in so many of these spaces. And yet, what's so important about the story is that even though she is there as just one of the few women who's observing, taking notes, she comes back, and she writes a series of columns in which she's grappling with the conversations, she's grappling with the ideas that other activists are thinking about, and she's being very transparent about where she stands. She's pushing back, she's pointing out what she sees as effective, but not as effective. And it just becomes this very public dialog in which she's pulling others, in which she's allowing others to play a part. And for me, it is just so remarkable to see how journalism, how writing, of course, combined with traveling, become avenues through which someone like Marguerite Cartwright, become at the center of this history, even as if you only focused on the more formal processes, you would never pay attention to her. And in fact, most people don't pay attention to her and women don't receive much attention in many of these mainstream narratives on the period. But by focusing on them, I show how even those who we might not pay attention to play a role in shaping and just to give another example, what ends up happening is as she's traveling, as she's attending these events, she's she's actually building connections, real connections. She, in fact, develops a strong relationship, a really, I think, a friendship with with someone like Nkrumah. And she is able to, at some point, she's a connector. She's able to introduce African leaders to African American leaders in different moments. I talk about in the book, for example, how she's the one who makes sure that Reverend Martin Luther King Jr receives an invitation from Nkrumah to attend independent liberation events. And so it just shows that even at a practical level, at a you know, at the relational level, she plays this, this important role in in drawing the connections between what what's happening, in the west, what's happening globally, and particularly in the case of the African continent. And and so shedding light, I think, on her story, helps us think more broadly about this history and we, I think we end up more, I think, more exciting and enriched perspective when we center the stories of those on the ground operating outside traditional halls of power.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:57

You talk in the book about how Cartwright notes that she's frustrated that Black people in general aren't payed more attention to at the United Nations. Could you talk a little bit about the interactions that these Black women leaders have with the United Nations, the kind of hopes that they're pinning on the UN, it's not maybe living up to what they hope?

Dr. Keisha N. Blain 32:16

So this is really a fascinating story, because one of the things that I emphasize in the book is perhaps mixed responses to the United Nations. On the one hand, there is excitement, because some activists see the United Nations, certainly its formation, as a moment where they're able to, in a formal sense, advocate for human rights and ensure that those rights are extended to Black people the world over. Many of them are, of course, in 1945 thinking about colonialism. They're thinking that presence of the United Nations would be one avenue through which to bring an end to white colonial rule. And what they do find is some frustration, because, internally, because the United Nations as a new organization, they are trying to craft something that is, that is new for the time that will involve so many different nations, so many different people from diverse backgrounds. Naturally there, there will be disagreements. Naturally there will be diverse, diverse perspectives in what exactly is the vision of human rights that would be able to to apply broadly across the globe. And what someone like Mary McLeod Bethune encounters, and so I talk about her as one of the delegates, as one of the African American delegates, who's who's there, along with WEB DuBois and Walter White. And part of what's happening is all three of them at various moments, they're trying to make sure that the concerns of people of African descent, that the concerns are heard at the drafting of the charter. They're trying to make sure that Black people are not being sidelined. And it's it's difficult for them, of course, encountering resistance within and externally, and yet it doesn't stop them from constantly trying. But part of that resistance, I think, broadly, signals to so many activists that this may very well be an important space, but it might not actually help you accomplish what you're trying to accomplish. So it is a mixed story, and as I move from individual to individual, you get the sense that there is, of course, initially, a lot of excitement. In fact, I talk about journalists, another journalist, Paulette Nardal, who's from Martinique, and I talk about her as the first Black woman to formally work for the United Nations as an area expert in 1946, And she writes about the UN in very glowing terms. She talks about it as a new hope. For her, this is going to be the breaking point. This will be the moment where Black people will be able to experience the rights that they have been advocating for. This will be the moment where perhaps colonialism will come to an end. So she starts off with this very optimistic point of view, and you see that others are similarly experiencing that sense of excitement and hope, and as time progresses, and as I'm looking through the primary sources and thinking and really spending time with the correspondence, it's it becomes clear that there's now a lot of doubt, that there are people who are outright saying, "Listen, it's just not going to happen through the United Nations. We have to work around it. You know, we have to figure out other strategies, because they're not willing to go as far as we want them to go to secure rights for Black people and other marginalized groups." So it is a mixed story, and to Marguerite Cartwright, she has a sense of hope. She I don't think she's not oblivious to the challenges, but she maintains a sense of hope that this is important. And her sense is that Black people need to be paying close attention to the United Nations. They need to be paying attention to the conversations that's taking place, to the developments. And she is frustrated that that she finds a bit of cynicism among many people as she's talking about it, at least some people see her as a bit idealistic, and they're not as enthused. But she makes a case in her columns. She's she's emphasizing what's happening. She's going to these meetings, and she's emphasizing what's happening in order to say to readers, "Look, keep your eye on the United Nations. Keep your eye on these developments. As we are advocating for civil rights in the national context, we need to be fully tapped in to what's happening globally, because, in fact, it will strengthen our argument for expanded political rights of the US context."

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:22

I wanted to ask you, too, you've been very involved in public history. Just wonder if you could comment on the importance of public history in this moment?

Dr. Keisha N. Blain 37:32

I think it is so important. I've been deeply committed to this for so many years, and perhaps this moment compared to so many others I have, I feel a sense of urgency when it comes to doing this work, because, as we have been seeing across the nation, it's not only the amnesia, because there's that part of the kind of national amnesia where people don't necessarily seem to remember many things, but there's the intentional erasure of this history, and I thought a bit about that too as I was writing the book. So just as one example, I relied in telling Marguerite Cartwright's story, I relied heavily on her papers, one main collection at the Amistad Research Center at Tulane in New Orleans. And in the past few weeks, I was, of course, not surprised, given everything that's happening nationally, but I was certainly disheartened when I heard the news that they had lost significant funding from the Federal Government and they needed to lay off staff members, and they are now trying to raise funds because, quite frankly, they're unsure about what the future looks like. And I remember just reflecting on the reality that who knows in 10 years whether researchers will have access to this material, simply because resources are drying up, certainly at a federal level, and, and there is this kind of disregard for scholarship, for research on not only Black people, but but other marginalized groups. And, and here's where I think public history matters so much. For me, it's important to write the narratives that people can read and understand in the broadest sense, that they don't have to have a college degree to read and understand the work that I'm producing. And also, I'm committed to making sure that the information is available in so many different mediums, because some people will listen to this podcast, but will not actually read this book, and that's okay, but I want them to be able to have this information, because with all the forces at play, with all the external challenges, with all the efforts to suppress the history, to silence the voices of those who are doing this work, to pull funding. Working to make it harder for researchers, I think what will last, quite frankly, are these narratives that we are continuing to circulate. And here I think about the power of oral traditions when we don't have the text to be able to tell these stories to our children, and they can tell the stories to to their their children and so on. So I think about public history in this very urgent sense, and the this realization that as much as I love being able to engage scholars, and of course, I do that all the time, I am deeply committed to making sure that I am in dialog with with folks who who may never see my classroom, but will need to know and understand this history as they navigate this world. Hopefully what I'm sharing will help them figure out even how to strategize within their communities, how to respond to the challenges they're facing. There's a lot we can learn from history. So I'm inspired by that.

Kelly Therese Pollock 40:57

"Without Fear" is a tremendous book and very readable. So I'd like to encourage listeners to get a copy. Can you tell them how they can do that?

Dr. Keisha N. Blain 41:06

The book is available wherever books are sold. I encourage people to visit their local bookstores. I think independent bookstores, especially now, need our support as much as possible. So that's where I would start.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:20

Well, Keisha, thank you so much for speaking with me today.

Teddy 41:40

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History or on Facebook @UnsungHistoryPodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Keisha N. Blain

Dr. Keisha N. Blain, a 2022 Guggenheim Fellow and Class of 2022 Carnegie Fellow, is one of the most innovative and influential young historians of her generation. She is an award-winning historian of the 20th century United States with broad interests and specializations in African American History, the modern African Diaspora, and Women’s and Gender Studies. She completed a Ph.D. in History from Princeton University in 2014. She is a Full Professor of History and Africana Studies at Brown University and an affiliated faculty member in American Studies and in the Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Studies. A former columnist for MSNBC, she is now the editor-in-chief of Global Black Thought, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press. The journal features original, innovative, and thoroughly researched essays on Black ideas, theories, and intellectuals in the United States and throughout the African diaspora.

Blain is the author of Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom, which was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in

2018. The book won the 2018 First Book Award from the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians (for the best book on women, gender, and sexuality) and the 2019

Darlene Clark Hine Award from the Organization of American Historians (for the best book on African American women’s and gender history). It was also selected as a finalist

for several prizes, including the 2018 Hooks National Book Award and most recently, the 2020 Ida Blom–Karen Offen Prize in Transnational Wom…

Read More