John H. Johnson & Ebony Magazine

When businessman John H. Johnson died in 2005, Ebony Magazine, the monthly photo-editorial magazine that he launched in 1945, reached an estimated 10 million readers. Under the direction of executive editor Lerone Bennet Jr. for several decades, Ebony helped shape Black culture and perceptions of Black history. Johnson Publishing Company helped shape Chicago history, too, when they opened their Loop location in 1972, at 820 S. Michigan Ave. The now-iconic 11-story, 110,000 square-foot building was the first major downtown building to be designed by an African American architect, John W. Moutoussamy, and the first skyscraper owned by an African American in the Loop.

Joining me this week to help us understand more about Johnson Publishing is Dr. E. James West, a Lecturer at University College London, co-director of the Black Press Research Collective, and author of Ebony Magazine and Lerone Bennett Jr.: Popular Black History in Postwar America, A House for the Struggle: The Black Press and the Built Environment in Chicago, and Our Kind of Historian: The Work and Activism of Lerone Bennett Jr.

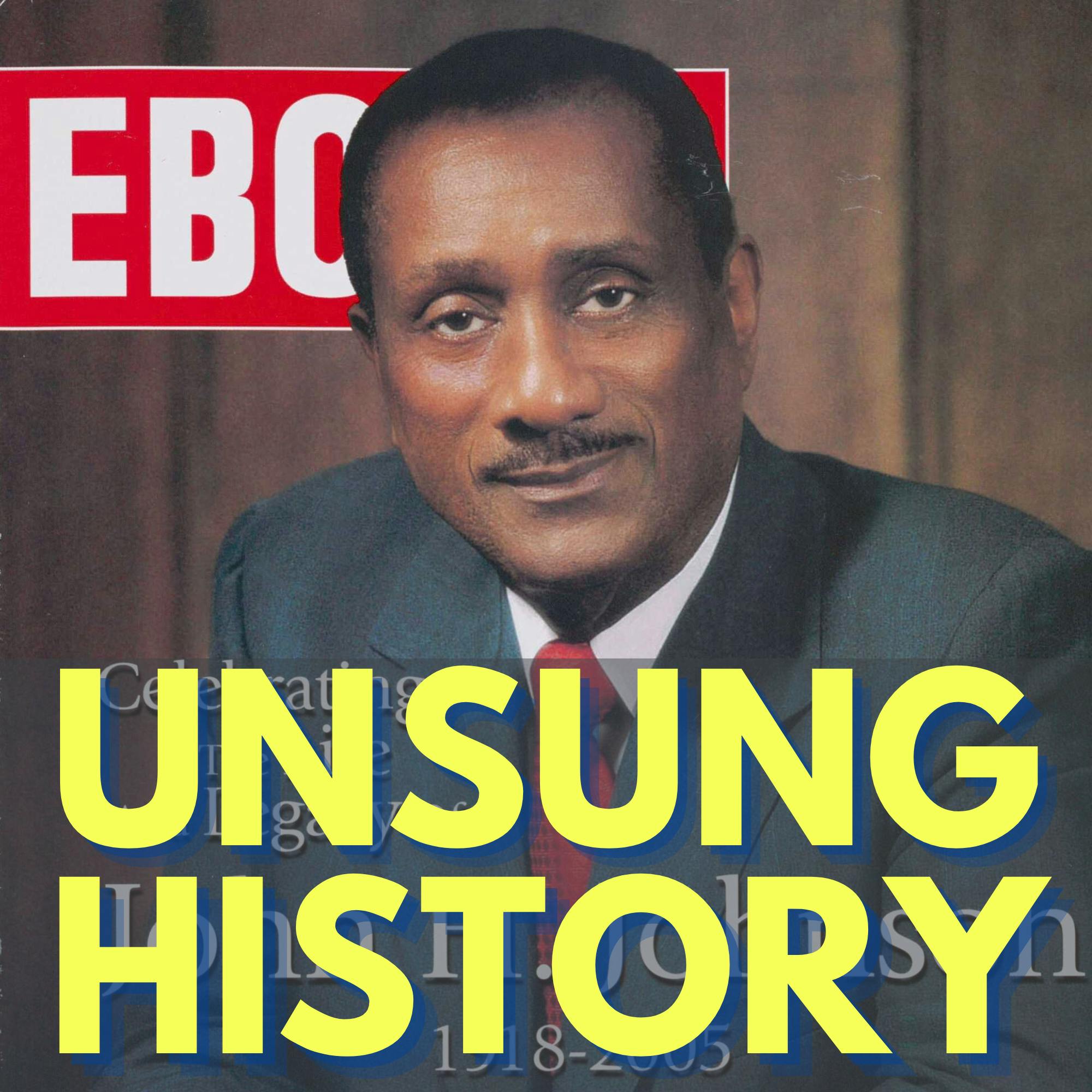

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-roll audio is from the Sol Taishoff Award ceremony on February 25, 1986, where Don Hewitt, John Johnson and John Quinn were recognized for Excellence in Journalism. The video was aired on C-SPAN and is in the public domain. The episode image is “Ebony magazine, Volume LX, Number 12 honoring the life of John H. Johnson, the founder of Johnson Publishing Company, publisher of Ebony magazine,” from the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Bunch Family.

Additional Sources:

- “Succeeding Against the Odds: The Autobiography of a Great American Businessman,” by John H. Johnson and Lerone Bennett, Jr., Johnson Publishing Company, October 1, 1992.

- “John H. Johnson, 87, Founder of Ebony, Dies,” by Douglas Martin, The New York Times, August 9, 2005.

- “The Radical Blackness of Ebony Magazine,” by Brent Staples, The New York Times, August 11, 2019.

- “Lerone Bennett Jr., Historian of Black America, Dies at 89,” by Neil Genzlinger, The New York Times, February 16, 2018.

- “75 Years of Ebony Magazine,” The National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian.

- “Under new ownership, 'Ebony' magazine bets on boosting Black business,” by Andrew Craig, NPR Weekend Edition Sunday, October 31, 2021.

- “New apartments pay homage to Ebony/Jet building's history,” by Dennis Rodkin, Crain’s Chicago Business, September 9, 2019.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.This is the second episode in our short series on Chicago History. This week, we're focusing on John H. Johnson, and his Johnson Publishing Company, which published Ebony and Jet magazines, and which was headquartered in Chicago. John H. Johnson was born in Arkansas City, Arkansas, on January 19, 1918. There was no high school for African American children in Arkansas City, so Johnson and his mother joined The Great Migration, moving to Chicago, where Johnson attended DuSable High School on the south side of the city. At DuSable, Johnson edited the school's newspaper and yearbook. In 1936, when he graduated high school, Johnson spoke at a dinner hosted by the Urban League. The dinner was attended by Harry Pace, the president of the Supreme Life Insurance Company, the first African American owned insurance company in the northern United States. Johnson impressed Pace, and Pace offered Johnson a job at Supreme to earn money while he attended the University of Chicago. At Supreme, Johnson edited an internal company magazine. While he was compiling news about the Black community, he came up with the idea for a magazine for Black readers. In 1942, Johnson launched Negro Digest, modelled on Reader's Digest. When he couldn't find financing, he took out a loan with his mother's new furniture as collateral, and sent out letters soliciting subscriptions. In less than a year, the circulation of the magazine jumped from 5000 to 50,000. By this time, Johnson was married to Eunice Walker. When Johnson came up with the idea of creating a flashier magazine based on the model of Life Magazine, it was Eunice who suggested the name "Ebony" for the monthly magazine. Johnson later wrote, "Ebony was founded to provide positive images for Blacks in a world of negative images and non images. It was founded to project all dimensions of the Black personality in a world saturated with stereotypes. Our mission is to tell Black America and the world what Black America is thinking, doing, saying, feeling, and demanding." Ebony Magazine was an overnight success. The first run of 25,000 copies of the November, 1945 issue sold out immediately at 25 cents a piece. By 2005, the magazine reached an estimated 10 million readers. Johnson followed up the success of Ebony by launching Jet, a weekly news magazine in November, 1951. Johnson Publishing Company stopped publishing Negro Digest in 1951, as Ebony and Jet cannibalized some of its readership. In 1961, they revived the periodical with Hoyt W. Fuller serving as editor. In 1970, the magazine was renamed "Black World," and was devoted to Black arts and culture around the globe until it was discontinued in 1976. In 1958, writer and social historian Lerone Bennett Jr. was named executive director of Ebony. He remained in the position until his retirement in 2005, shaping decades of the magazine's coverage. In 1972, Johnson Publishing Company moved into the Loop, the downtown area of Chicago, at 820 South Michigan Avenue. It was the first major downtown building to be designed by an African American architect, John W. Moutoussamy, and the first skyscraper owned by an African American in the Loop. The 11 storey 110,000 square foot building was home to Johnson Publishing for decades, until it was sold in 2010. The building, which now houses luxury apartments, still retains its iconic Ebony /JPC/Jet sign, which now overlooks a swanky rooftop deck. In 1982, Johnson was the first African American to appear on Forbes Magazine's list of the 400 wealthiest Americans. In 1987, Johnson's daughter, Linda Johnson Rice, became president and COO of Johnson Publishing. In 2002, she was promoted to CEO, becoming the first African American woman CEO among the 100 largest Black owned companies in the United States. On August 8, 2005, John H. Johnson died in Chicago at the age of 87. His funeral, held in Rockefeller Chapel on the University of Chicago campus, filled the chapel. Guests included former President Bill Clinton, then-Senator Barack Obama, Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, Louis Farrakhan, Lerone Bennett and then-Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daly. In 2016, Johnson Publishing Company was sold to a private African American owned equity firm in Texas, called Clear View Group.

In May of 2019, Ebony announced it was ending publication and filing for bankruptcy. Former NBA player and businessman, Junior Bridgeman, purchased it for $14 million. Michele Ghee became CEO of Ebony and Jet, and Ebony relaunched in digital format in March, 2021. Joining me this week, to help us understand more about Johnson Publishing, is Dr. E. James West, a lecturer at University College, London, co-director of the Black Press Research Collective, and author of three books about the Black press in Chicago: "Ebony Magazine and Lerone Bennett Jr: Popular Black History in Postwar America," from the University of Illinois Press, 2020; "A House for the Struggle: the Black Press and the Built Environment in Chicago," from the University of Illinois Press, 2022; and "Our Kind of Historian: the Work and Activism of Lerone BennettJr," University of Massachusetts Press, 2022.

Presenter 8:57

Over the past 40 to 50 years, John has shown us a thing or two about publishing and entrepreneurship. The National Press Foundation is therefore honored to present its Award for Distinguished Contributions to the Quality of Journalism to John H. Johnson.

John H. Johnson 9:20

Thank you very much. First of all, I'm delighted to be in Washington today, receiving this award. It is not the Washington I remember 30 or 40 years ago. As a matter of fact, I was delighted that they were able to find my reservation today. I passed I passed by the Shoreham Hotel. And I recall that it was exactly about 30 years ago that one of our advertising men and I had a reservation, a confirmed reservation, in writing, to room at the Shoreham, and when we arrived, the man looked everywhere and he just simply couldn't find our reservation. So the young man and I, and this was long before the sit-ins. And without any desire to have a confrontation, we simply didn't have any where else to stay in Washington. So we said, "We'll just have to sit here in the lobby all night." And it was about five o'clock and the Daughters of the American Revolution was meeting. As a meeting ended, the ladies came out and saw these two Black men sitting there, and they say, "Eek, eek, eek," and finally, the manager came over and he said, "All right, fellas, you win. I have found your reservation. But I will never never find them again." Although the Shoreham has sent me many invitations to stay there, I have not found it possible to stay there again. But I want you to know that that that little incident is indicative of the great progress we've made in our country. Because I don't ever have to worry now about finding my reservations. I only have to worry about whether I can pay the bill. And I'm pleased that you've given this recognition to Ebony, and it's a recognition not just for me, but for my family, for the many people who work with us, for our advertisers, and the many people of goodwill, white and Black, who have helped me along the way. And so Ebony has tried to portray the positive aspects of Black life. We've tried to make Black people proud of themselves. And we've tried to give whites a view of Blacks that many of them would not otherwise get. So I'm very pleased that we've been able to survive for all these 40 years. And I'm more than pleased that you have given me this recognition, which I'm sure will encourage other minority persons to persevere, as I have tried to persevere, and to succeed, as well, as I hope I've done. Thank you very much.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:17

Hi, James, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. E. James West 12:19

Thanks for having me. Looking forward to talking.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:22

Yeah. I am always excited to talk about Chicago in any form. This is an exciting part of Chicago history that I didn't know a lot about. So I wanted to start by asking, maybe if you could just talk about what the Black press is, and the work that the Black Press Research Collective does for listeners who maybe aren't quite familiar with that terminology, and that part of research?

Dr. E. James West 12:48

Sure. So I'm co-director of, of the BTRC, which is based at Johns Hopkins University. And it was founded primarily directed by Professor Kim Gallon, who now works at Brown University. And last year, she invited me to come on board as co-director, because we've got quite a lot of things that we want to do leading up to 2027, which is the bicentennial of the Black press in the United States. So yeah, the term Black press is a good question, because I think some people might not know what that term means. And some people have a general sense of what it means. Broadly speaking, it's referring to Black owned or operated periodicals in the United States. So you might have heard of papers like the Chicago Defender, or the Pittsburgh Courier, you know, that's an example of an African American newspaper that we might think of as being part of the Black press. Historically, that term, we go back to 1827, and Freedom's Journal is generally seeto be the first African American newspaper. Generally, when people use the term "the Black press," you know, they have used it to refer specifically to Black newspapers. In the research that I do, I talk about Black periodicals more generally. So I include magazines in that. Some people have expanded that further to include, for example, Black radio, as part of the Black press. My personal usage of the term is, it doesn't really include Black radio. It is mainly focused on African American periodicals in terms of newspapers and magazines. And I'm using the term Black and African American interchangeably throughout this interview. But when I talk about the Black press, I'm mainly talking about the Black press in the United States. So you have Black owned periodicals n other places in the Caribbean, in Africa and Britain, and they have really interesting and interconnected histories; but the majority of my work focuses mainly on the modern United States.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:56

And how did this come to be a subject that you got interested in? And you've written prolifically about it. So how did that research interest start for you?

Dr. E. James West 15:06

It's always, I think, an interesting question. Because you know, I'm a white British scholar, and I didn't grow up with these publications. And it's, you know, something that is useful to reflect on that myself, and also people who read my work, I think it's useful for them to know their positionality. For me, the entry point into the Black press really was thinking about Johnson Publishing Company, just a bit of background. So I did my education, university level education in the in the United Kingdom. And I was doing an undergraduate dissertation, I started my undergraduate degree in 2008. And that was right around the time that Google Books were starting to digitize quite a lot of periodical material, including some of the major publications of Johnson Publishing Company, which is one of the largest Black publishing companies in the world. So Ebony Magazine, Jet Magazine, Negro Digest, later known as Black World Magazine, they were all digitized, or at least large sections of their back catalogue were digitized and freely available and searchable through Google Books. So around the time that I was thinking about undergraduate dissertation topics, I became aware of, of these sources, and I just found them really interesting. And there's something quite tangible about magazines, that's really interesting to me, and also you know, all of the different parts of that single text. So you might think of a magazine as a single primary document. But then contained within that, you know, you have letters to the editor, you have editorial content, your opinion pieces, you have advertising, you have all of these things going on. And I just found that really interesting and seeing the way that they, you know, interacted with one another. So that was the background really. And then my PhD dissertation was focused primarily on Ebony Magazine on on an editor called LBennett Jr, and that became, ended up becoming my first book projects. And then since then, I've broadened my interest out to thinking about the Black press in Chicago, more generally, so still looking at Johnson Publishing, but also looking at other influential Black newspapers and magazines in Chicago. And then obviously, the work of the BTRC is more broadly defined. So we're primarily interested in the Black press across the entirety of, of the United States.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:36

Let's talk some then about the relationship between the Black press and Chicago, specifically. Why why was Chicago a hotbed of Black publications? What is the relationship between the city and you talk, of course, in a more recent book about the Built Environment of Chicago and the relationship with the Black press? So I wonder if you could just sort of expand on that. And, you know, what, what is it about Chicago, or what is it about the Black press that makes it into Chicago? You know, what, what is this relationship?

Dr. E. James West 18:06

Yeah, it's a really interesting one. I think a lot of it goes back to Chicago being a really important and arguably the center of Black business in the 20th century. And if you look at, for example, Black Enterprise Magazine, which is a popular magazine for African American professionals, which started in the 1970s, you know, into the 1970s, when it ranks when it looked at cities and rank them in terms of Black business power, Chicago, often was on the top. And that's not necessarily surprising. It's a very, very large city. And in terms of African American population, and depending on how you measure it second, secondary to New York. But I think there is a specific type of business culture in Chicago and all this and also the specifics of segregation in Chicago. Chicago remains one of the most intensely segregated large cities in the United States. You have a very distinct vibrant Black Business District and Black business culture that that emerges on the south side of Chicago in the first half of the 20th century. And that really underpins the formation of some of these really big influential Black periodicals. So papers like The Defender, Johnson Publishing, as an entity, even things like Muhammad Speaks, which was the official newspaper of the Nation of Islam. At one time, these were all the most widely selling Black periodicals in the country. And they're all based within, you know, just a few a few miles of each other. And, you know, there's a lot of work that's been done around Chicago and a history of Black Chicago and the way in which segregation and racial formations helped to shape and contain African American populations on the south side. And in tandem with that you also see maybe an unintended consequence of that confinement, which is the emergence of this vibrant Black cultural, artistic, business societies and spaces. And that's one of the, you know, really interesting paradoxes. I think, Gerald Horne calls it the the Jim Crow paradox in that you have this site containment, and then it becomes a space for the cultural entrepreneurial activity. So I think, yeah, for Chicago, that's not solely the case in Chicago, but I think in Chicago, you have an intensified version of this. And that leads to the formation of some, you know, it's not just newspapers or periodicals, you know, some of the most important, like insurance companies are based out of Chicago, you know, other types of businesses come out of come out of that milieu, on the south side.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:55

And then, of course, Johnson Publications, wants to move further downtown, you know, wants to sort of leave this idea of this south side and be maybe closer to the heart of the city. Could you talk a little bit about that move when they move to 820 South Michigan, what Johnson, John H. Johnson is looking to do, and what that signifies when he does move headquarters to that location?

Dr. E. James West 21:34

Yeah, so again, it's a really interesting tension. The Johnson Publishing building, even today, it hasn't been owned by Johnson Publishing for more than a decade, it remains one of the most recognizable business locations for for African American business in the country. And you know, recently there was a really big struggle over whether the building was going to be landmarked, or whether it was going to be demolished. And there was a lot of contestation around what which parts of the building will be saved. But Johnson had been wanting to build his own building for quite a long time. And he decides really, in the early 60s, that he's going to double down on this project. And the problem is that he can't really find someone to lend him the money. White lenders are reluctant to lend to a Black businessman. He'd had a lot of trouble moving into his previous building, which was about a mile further down on South Michigan Avenue. He'd actually had to disguise himself as the janitor to inspect the building, because the owners of that building, it was called the Hursen Funeral Home, they didn't want to sell to an African American businessman, he had to change the name of his company. And it was originally known as the Negro Digest Publishing Company after the name of his first publication. And then he changed it to Johnson Publishing, which was a more race neutral designation. So he's, he's had it on his mind for a long time that he wants to build, you know, this iconic building, this this concrete symbol to his own business acumen, but also to the broader gains made by African Americans during the period since since World War II. And they end up settling on this site at 820 South Michigan Avenue, and the building is designed primarily designed by an African American architect called John Moutoussamy, and it's, it's often credited as being the first Black owned building to be to be constructed on the on the Loop since basically the the city's founder, Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, constructed a log cabin like this is the myth that Johnson liked to propagate. But this move is, as you said, it takes the company away from what had historically been its home on the south side. Johnson Publishing, when it started in the early 40s, it was actually started out of a back office of the Supreme Life building at 35th Street, which was the home of a really important Black insurance company. And the company in its first 10 or so years, really was moving between different sites on the south side, and its locality and its proximity to where the majority of African Americans in Chicago at that time were living was a key part of the appeal of cementing its, you know, status. And he gets some backlash when the company moves uptown. Because, you know, some readers of the publications see this as essentially a retreat from, you know, its connection to the African American community. And this is coming particularly in the early 70s. This is coming at a time where there are increasing tensions and class divisions between, you know, an upwardly mobile Black middle class, who were who were taking advantage of the gains of the civil rights era and the victories of the civil rights era, and then an increasingly marginalized working class poor, Black inner city. And that's the case of Chicago. And that's the case in, in other areas of the country as well. So yeah, I think in my book where I talk about the buildings, and I really focus on the buildings of Chicago's Black press, that building, the Johnson Publishing headquarters is a really interesting way to think through some of these interconnected tensions, because on the one hand, it's this symbol of Black entrepreneurial success and the gains of the Black middle class. And that's, you know, the content that's generally seen through the magazines themselves, you know, they're quite aspirational. They're quite middle class, they're quite bougie, a lot of the time, particularly Ebony Magazine, but this is coming against this backdrop where a lot of African Americans in Chicago aren't seeing the fruits of that success. It's coming against the backdrop of Black Power contestations, you know, the murder of Fred Hampton, the impact of the '68 riots in Chicago, all of these things. So yeah, the building becomes this space where people, you know, protest outside of it, people want to be in it, you know, people want to visit. So it's, yeah, it's a lot of conflicting emotions.

Kelly Therese Pollock 26:16

So let's talk some about how that tension plays out in the pages of Ebony as well. And especially you write about Lerone Bennett, Jr. and the way that he is trying to trying really to get history and intellectual content and a more progressive, radical interpretation of Black history and Black politics onto the pages. And of course, that is not really what John H. Johnson is trying to do. And yet the two streams coexist on the on the pages of Ebony Magazine. Can you talk a little bit about that tension and the way it plays out? And really how Bennett Jr. is successful in at least some of the vision he's trying to get onto the pages?

Dr. E. James West 27:05

Sure. So for people who aren't familiar, Lerone Bennett was a leading Black popular historian and editor. He he might be most well known for a book that he wrote about Abraham Lincoln, which is very critical book called, "Forced into Glory," and how it caused a controversy around the turn of the 21st century. And it was it was based on an article he'd written in Ebony, about 30 or 32 years earlier. Bennett is part of what you might describe as a cohort of more left leaning editors within Johnson Publishing. And this is one of the really interesting things I've always found about Johnson Publishing as an institution. It has a diversity of perspectives of people working within it. So even from the publication's founding, John H. Johnson is generally seen as a more moderate, in some ways, conservative figure. But he you know, one of the very first people that he employed was a lapsed white communist called Ben Burns, who was editing and directing a lot of the content within the first 10 years or first eight years or so, of the company. And it is this space, a really interesting space, and there's a liquidity of opinions and then also lots of people would contribute work to Ebony and the other publications as well. And yeah, Johnson, particularly in the second half of the 60s, Johnson starts to butt heads with quite a few editors, particularly a man called Hoyt Fuller. Jonathan Fenderson, who wrote a really great book about Hoyt Fuller and Negro Digest, Black World, which I believe is called, "Building the Black Arts Movement." He talks a lot about this relationship between Fuller and Johnson. And it ultimately culminates in Fuller's abrupt firing, and the cancellation of, of Black World as a magazine. But Bennett is able to negotiate his relationship with Johnson much more effectively, he's able to accrue quite a lot of power within the company. And he's able to strategically leverage that to invite you know, more radical or more progressive contributors. He himself writes some really interesting material for which is very out of keeping with the standard editorial tone of of Ebony, which is celebrity-like African American celebrities, photo ops, puff pieces, stories about where to go on holiday, fashion, that type of thing. And in the midst of all this, you find articles from Bennett talking about Black history and Marxist theory. And you know, it's interesting to see how all goes together. And yeah, part of my first book, and then I wrote a subsequent book, which is a full biography of Bennett, which is called, "Our Kind of Historian." And yeah, a lot of those books were nice, just trying to work out what the deal was with Bennett and how he was able to navigate his space within this institution. And I'm not really sure if I ever was fully satisfied with the answer that I got to. But I think a lot of it was based around his the specifics of his relationship with John H. Johnson, because they, you know, were philosophically very far apart on a number of things. But they also maintain a very strong friendship. And I think a key part of that was they were both born in the south at a certain moment in American history, and they were raised in the south. I think, you know, as the crow flies, I think they might have been about 50 or 70 miles away from each other wherever they were actually born, in, you know, Mississippi and near the border of Arkansas. So I think that background and that cultural experience goes a long way to shaping their later, professional and personal relationship. Yeah, that's a that's a quite long winded way of saying, "I still really haven't worked out what the deal was with Lerone and Ebony, but it was a lot of fun trying to try and find out."

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:24

Well, and there's a similar kind of relationship, I think, and you talk about Ebony as Black history text. And so there's this way in which Ebony is reflecting Black culture of any moment in time, but also is directing it because it has this enormous reach, enormous readership. And I think you say at one point with pass along copies that reaches maybe 40% of African Americans. So can you talk about that and the way that Ebony, and to a lesser extent Jet are shaping Black culture as much as they are reflecting it?

Dr. E. James West 31:24

Yeah, that's a really, really great question. And in terms of the reach of I'm going to focus on Ebony for the purposes of this, it's, you know, it's sometimes difficult to tell because all periodicals like to, to an extent inflates their reach, and because that's how they get advertisers based on circulation guarantees. So you have the guaranteed circulation in terms of the amount of copies of the magazine that were printed, and Ebony's a monthly magazine. So at its peak, it was printing around 2 million copies a month. But then you have the pass on readership and then pass on readership basically means the number of people who read a significant portion of that publication for every copy that's distributed. And this is particularly important for African American readers, because there's a really long history of magazines or publications being distributed more widely within the African American community. So you know, if you go back to the 19th century, when Black literacy rates are quite low, you have this really interesting history of public readership and people reading out content for listeners and, you know, magazines and periodicals being circulated within towns passed from reader to reader, you know, you have stories of publications being passed around until they're literally falling apart. And Ebony, generally argues that it has a pass on readership of about four to five people per issue. So at certain points based on the paid circulation, and then the broader pass on market, is arguing that it reaches more than 40% of the adult African American population each each month, which is an extraordinary level of saturation, and like it's not really comparable to, to anything of its kind. And, yeah, that gives the magazine an enormous amount of influence. And Ebony in particular, as well. It's a magazine, that's a very public magazine, it's, you know, it's cut, it's that magazine that you would have on the coffee table when you go into the house or as the magazine that you might see other people reading and the physical size of the magazine as well. It lasted until the 80s. And then it had to downsize to come in, in with industry standards, but it's a really, you know, oversized magazine, it's a really big when you open it out, it's a really big document text. It takes up a lot of space. So yeah, it's really interesting to trace that impact. And for me, one of the arguments that I was trying to make in my first book about Ebony as a Black history text was basically trying to show just how many people were reading the Black history articles that people like Bennett were writing, and then how that was shaping broader attitudes towards African American history, particularly during the 60s, 70s, and into the 80s. And John H. Johnson, in his autobiography that was, was actually co written by Bennett Jr. And that gives you another sense of their relationship. He has this really interesting quote, and he says, "You know, I was never interested about making history, I was interested in making money." But if, you know, one kind of led the other in the sense that he and the people around him, I mean, of course, it wasn't just Johnson, but they built an extraordinarily successful Black business enterprise, and then through that gained all types of cultural, historical, educational influence that maybe they couldn't have possibly anticipated when they started. And you see it in all in all manner of ways. I'll give you just two quick examples that are, I think, are useful. One is that Johnson, in the success of particularly Ebony, enabled the company to found the Johnson Publishing book division, which became one of the most popular and widely distributing Black book companies in the country. And pretty much all of Lerone Bennett's history books, including "Before the Mayflower," which is a massively popular text, probably rivaling John H. Franklin's "From Slavery to Freedom" as one of the most widely read Black History surveys of, of 20th century history. That was published by the Johnson book division. So that's one aspect of that influence. Another is if you look at documents from the Civil Rights era, and if you look at Freedom Schools, and those types of material, often you will see Johnson Publishing documents turn up on those, you will see specific articles from Ebony. And that gives you a very granular insight into how these magazines were penetrating those types of spaces. And it's really interesting, because you see those types of articles alongside Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton's "Black Power," or Frantz Fanon, you know, those type of authors, and they are never authors that you would necessarily put in conversation or or text that you were put in conversation. So I think that's a really another really interesting insight into the educational impact of of Ebony, beyond what we might normally associated with the magazine.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:21

You mentioned earlier that a magazine has all these different sections, and one of them that you mentioned, that was really striking was ads. And I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the advertising within Ebony and the way that advertisers started to see the Black readership as a market that they could tap into. And especially striking, I think, is the way that Black history started to be commercialized. And the way they started to look at that in advertising. So could you talk a little bit about that?

Dr. E. James West 37:53

Yeah, sure. There's a couple of things that I would flag for people who are interested in this topic, just in terms of materials that they they might be interested in, in reading. I think, Jason Chambers, who's, he's written extensively on race and advertising. His book, "Madison Avenue, and the Color Line" is probably one of the best examples if you're interested in just a general overview of the historical relationship between African Americans and the advertising industry. I've started to work work more on this. I published an article in the Journal of African American History last year, which focused on really how advertisers started to use Black history as a marketing mechanism. And Ebony is one of the most important vehicles for advertising in the country. And Johnson actually is, is often credited with really being the first Black businessman or first Black publisher to break the color line in the advertising industry. So Ebony becomes really the first Black periodical that's able to attract sustained blue chip advertising contracts from big companies, you know, we're talking like Pepsi, Coca Cola, Remington, Ford, those type of companies, and that opens the door for a lot of other Black publications. But yeah, Ebony is another. Again, it the magazine, you just have all of these contradictions. So you'll have a article from Lerone Bennett Jr. and it will be explicitly presenting a quite a radical interpretation of someone like for example, Frederick Douglass, and then you'll have an advert which is using Douglass to present a very different vision of American history and also effectively using Douglass as advertising spokesman. And yeah, I think at certain points Bennett becomes very frustrated with this. I know that other editors at the company become very frustrated with this. Era Bell Thompson, who is you know, fantastically interesting editor and a really important character in the early history of Johnson Publishing, she has a quite prominent bust up with the advertising department over one advertising campaign in particular, which is, you know, Black history themed advertising campaign. And I think, you know, this stuff is important, because when we look around us now, you know, so much of the public's engagement with Black history is mediated through corporate interests. And what I mean by that is, you know, when you look at, for example, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and you look at the donation list, and like the big donors to that company, and you know, how they funded the construction of the museum. Or if you look at PBS documentaries about Black history, and then you know, where the money comes from, if it's the Ford Foundation, or if it's, you know, individual corporate foundations, that has an impact, right. And I think Ebony is a really critical tool for thinking about how we go from Black history being completely ignored by American culture, by American corporations to Black history being celebrated, but in a quite specific way, by American corporations. And that's a shift that really happens in the second half of the 20th century. And it's a shift that shapes the way that we think about Black history in both general and specific sense today.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:27

So I mentioned that you've written prolifically. Where can people find your books and some of your other writing?

Dr. E. James West 41:32

Yeah. Right. Yeah, it depends who you're measuring against. If you're measuring it against someone like Gerald Horne, and I think we're all we're all doing pretty badly. But the main things that I've written, I've written three books. The first is called "Ebony Magazine and Lerone Bennett Jr: Popular Black History in Postwar America," that came out in 2020. And then I wrote a book that, as I've already mentioned, expanded on that and was really more focused on Bennett. And it was a biography of Lerone Bennett. And that was called "Our Kind of Historian," and that came out last year. And then I wrote a book called, "A House for the Struggle," which was about Chicago's Black press and the Built Environment. And that also came out last year. And yeah, I sometimes write for, you know, Washington Post, or Slate or those types of outlets as well. So if anyone's interested in a specific example of the Black history stuff, and what I've been talking about in terms of Black History advertising, I wrote quite a fun piece for Slate last year on the Budweiser and Anheuser-Busch campaign on "Great Kings and Queens of Africa." So yeah, you know, that's a nice entry point for some people they might have, you might have grown up with that campaign, you might be familiar with the posters, when you might have seen in school when you were younger. So if you want a bit of backstory to that campaign, and how, and how Anheiser- Busch decided to bring together all of these Black artists to create these really interesting advertising artifacts then then that would be an entry point.

Kelly Therese Pollock 43:06

Excellent. I'll put links in the show notes so people can find those as well. Was there anything else that you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. E. James West 43:13

I think just circling back to Chicago, I know that Chicago is the theme that's running through a lot of these, these episodes that are coming out at the moment. And yeah, I think in terms of publishing, and Chicago, it's just another reminder of the diversity and complexity, but also contestations that characterize the Black experience in Chicago. And I think there's a lot of particularly in popular media, you have very specific and often quite simplistic and linear narratives about what that Black experience is. And often, it's focused on quite pejorative things. And, you know, looking at the history of an institution like the Black press in Chicago, I think it's a really great way of thinking about just how just, you know, just the layers to that community, and the way in which you have all of these tensions and contestations and conflicts, and there's no one single experience or history to tell about African Americans in Chicago. So yeah, I think that's just something that I hope that through the work that I do, I try and, you know, reiterate that and try and push back against the often quite simplistic narratives of Black life in Chicago that we tend to get.

Kelly Therese Pollock 44:37

Well, James, thank you so much. This was really a fun topic for me to get to learn about. Certainly anytime I am downtown now I'm going to be looking for the Johnson Publishing building and I'm just, I'm really excited to learn about this.

Dr. E. James West 44:53

Yeah, thanks for having me.

Teddy 44:55

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources usefor this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

E. James West

I'm a UK-based historian and writer. My work focuses primarily on histories of the Black press and Black Chicago. More broadly, I'm interested in the connections between popular history, race, media, and visual culture in and beyond the modern United States.

I am a Lecturer in Interdisciplinary Societies and Cultures at University College London. I'm also the co-director of the Black Press Research Collective, based at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

In addition to my books and academic writing, you can find my work published in (or featured on), outlets such as Black Perspectives, Slate, the New York Times, Nieman Reports, NPR, and the Washington Post.