The FTA & Antiwar Protests in 1971

In 1971, a group of performers calling themselves the Free Theatre Associates (FTA), including Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, began putting on popular antiwar shows for audiences of active-duty GIs. Over 10 months they performed near military bases all over the United States and in the Pacific Rim. The Pacific Rim tour led to a documentary, which was released briefly in July 1972 and then quickly yanked from theaters. To help us learn about the FTA, I’m joined by theater historian Dr. Lindsay Goss, Assistant Professor in the School Of Theater, Film And Media Arts at Temple University and author of F*ck the Army!: How Soldiers and Civilians Staged the GI Movement to End the Vietnam War.

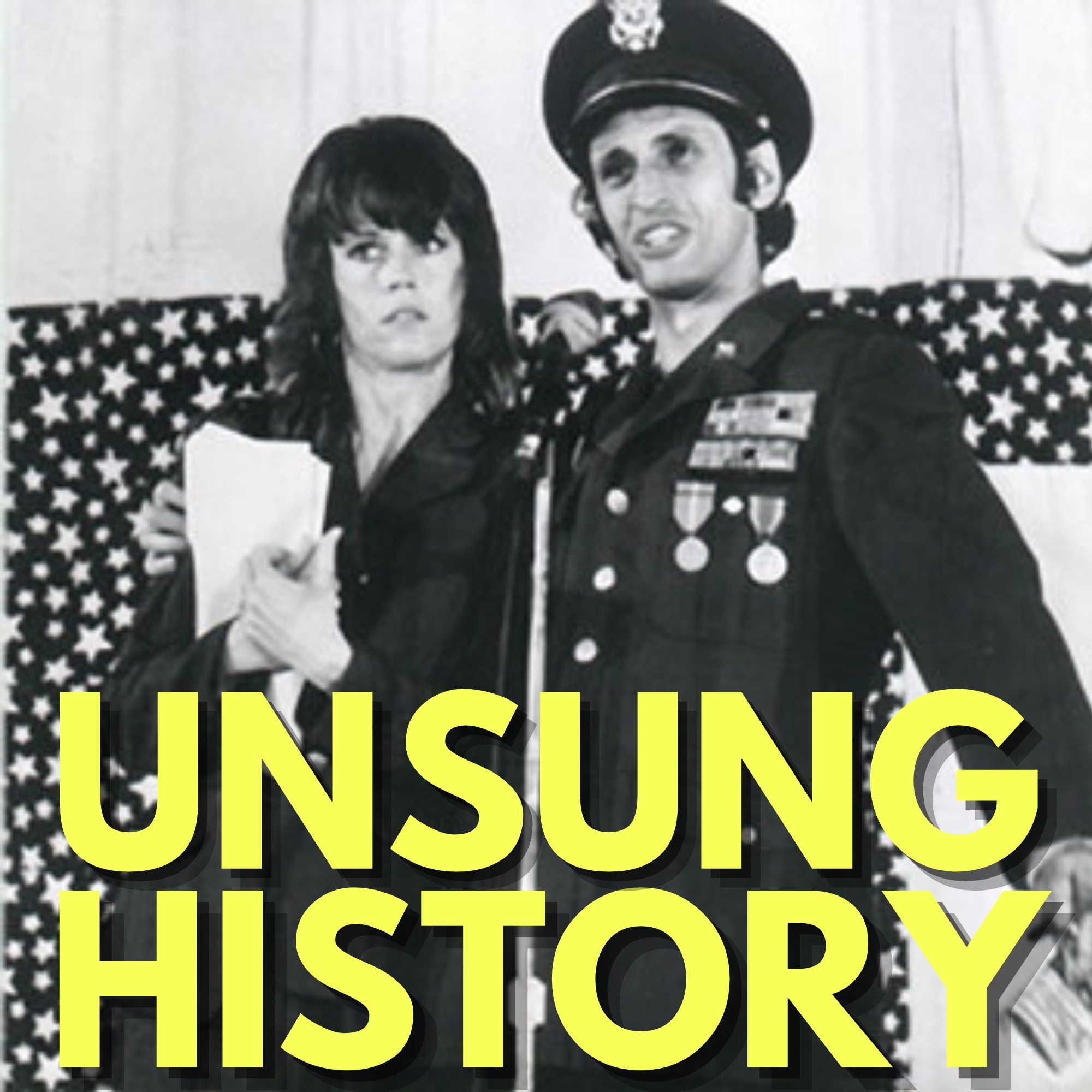

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier,” composed by Al Piantadosi with lyrics by Alfred Bryan; the performance by the Peerless Quartet in New York City on January 6, 1915, is in the public domain and is available via the LIbrary of Congress National Jukebox. The episode image is “Jane Fonda and Michael Alaimo in the FTA Show 1971;” the image is available via CC BY-SA 3.0 and can be found on Wikimedia Commons.

Additional Sources:

- “The Vietnam War: Reasons for US involvement in Vietnam,” BBC.

- “U.S. Involvement in the Vietnam War: the Gulf of Tonkin and Escalation, 1964,” Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, United States Department of State.

- “Tonkin Gulf Resolution (1964),” The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Vietnam: An unpopular war, but an important legacy,” by Kenneth Dodd, Kessler Air Force Base, January 27, 2016.

- “The Vietnam War,” Iowa PBS.

- “GI Movement Special Section“ coordinated by Jessie Kindig, Antiwar and Radical History Project, University of Washington.

- “How Coffeehouses Fueled the Vietnam Peace Movement,” by David L. Parsons, The New York Times, January 9, 2018.

- “FTA! Behind the Scenes on the Anti-war Show Tour in Asia,” by Elaine Elinson, Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

- “FTA [video],” directed by Francine Parker, 1972.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. In August, 1964, President Lyndon B Johnson asked Congress to give him the authority to increase the US military presence in Indochina. The immediate event that precipitated his request was the Gulf of Tonkin incident, in which two US destroyers stationed in Vietnam, reported that they had been fired on by the North Vietnamese forces. However, the US military presence in South Vietnam stretched back to the early 1950s, and by the time of the Gulf of Tonkin incident, Johnson was already looking for an excuse to send more troops, convinced that helping the South Vietnamese was the only way to prevent the spread of communism from North Vietnam to South Vietnam, which the US feared would then spread throughout Asia. On August 7, 1964, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which granted the president the right, "to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed forces," both to defend US forces and protect South Vietnam in defense of its freedom, until such time when the President deemed that the area was secure. With that permission, Johnson sent a major contingent of US Marines to Vietnam in 1965, and by 1968, over half a million US troops were stationed there, with the effort costing the US $77 billion a year. Over time, this lengthy Vietnam War became increasingly unpopular in the US. By 1960, 90% of US households had televisions, up from just 9% in 1950. That made the Vietnam War the first televised war for the United States population. Images of death and destruction broadcast into American homes helped sway public opinion against the war. Anti war protests began as early as 1966, and were especially big on college campuses where the students were of draft eligible age. It wasn't just the American public who opposed the war, though. That opposition also existed within the military itself. In the early days of the war, that internal opposition was small and isolated, with individual service members being punished for attending anti war demonstrations or refusing to fight. As the war and the opposition to war intensified, so did dissent within the ranks. At nearly every military base, anti war GIs began publishing underground newspapers. There were even two underground GI newspapers published in the combat zone in Vietnam, "The Boomerang Barb," near Saigon in 1968, and "GI Says," near the DMZ in 1969. By 1972, there were an estimated 250 such underground newspapers on US military bases around the world. Another way anti war servicemembers organized was in GI coffeehouses. The first GI coffeehouse, named UFO, opened in January, 1968, in Columbia, South Carolina, near Fort Jackson, one of the US Army's largest training posts. The explicitly counterculture venue was so popular among the base's soldiers, that over the next few years more than 25 GI coffeehouses opened near military bases, both in the US and overseas. On March 15, 1971, the Haymarket Square Coffee House in Fayetteville, North Carolina, near what was then called Fort Bragg, hosted a new show, headlined by Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland, Peter Boyle and Dick Gregory, calling themselves "The Free Theater Associates," or FTA. The group saw themselves as civilian supporters of the GI anti war movement. Their work was funded in part by the Entertainment Industry for Peace and Justice EIPJ, an organization founded by Fonda. The FTA had hoped to perform on the base, as USO shows did, and the United States Servicemen's Fund, USSF, made a formal request to the commander at Fort Bragg that was denied. The Haymarket Square Coffee House, meant to hold around 450 people, was packed with over 500 people per show over three shows, each paying the attendance fee of $2.50. Those funds went to the coffeehouse and the USSF. The performers themselves donated their time, and if they could afford it, their travel expenses. The show consisted of comedic sketches and explicitly political songs. In one popular skit, two of the performers acted as sportscasters covering an imaginary battle. They ended with the declaration that the day's casualties were light medium. Another popular segment of the show was their signature song, with FTA standing at first for "Free the Army" but over the course of the song, changing to "F the Army," or the Air Force, Marines, or Navy, depending on the audience. As the show traveled across the country to other locations near but never on military bases, many of the skits and songs changed, and cast members rotated in and out, though Fonda and Sutherland remained on for the entire run. That November, FTA did a benefit performance at Lincoln Center in New York City for a civilian audience of 2000 people, before leaving for a tour of the Pacific Rim. On Thanksgiving Day, 1971, the FTA tour played to a crowd of 4000 in Honolulu, some 2500 of whom were GIs. They followed that with huge shows in the Philippines, Japan and Okinawa. During the Pacific tour, Director Francine Parker filmed footage, both on stage and behind the scenes, along with interviews of active duty GIs. The resulting documentary, called simply "FTA," was released in July, 1972, but it stayed in theaters for only one week before its distributor, American International Pictures, pulled it from circulation and destroyed most of the copies of the film. It was rereleased in 2009, and can now be purchased on DVD or Blu-ray or streamed on Apple TV and Kanopy. Joining me now to help us understand more about the FTA is theater historian Dr. Lindsay Goss, Assistant Professor in the School of Theater, Film and Media Arts at Temple University and the author of, "F*ck the Army!: How Soldiers and Civilians Staged the GI Movement to End the Vietnam War."

Kelly 10:33

Hi, Lindsay, thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Lindsay Goss 10:36

Hi, thank you for having me.

Kelly 10:38

Yes, I am so excited to have learned about this history that I thought I knew all kinds of stuff about late 60s, early 70s. This was new to me. So tell me a little bit about how you first got onto this project. This book, I believe, comes out of your dissertation. So how did you get started on this?

Dr. Lindsay Goss 10:56

It does come out of my dissertation, although it even earlier than that in in like the early 2000s, I was an anti war activist in New York. And the Iraq Veterans Against the War, or Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans Against the War was a relatively new organization. And I was involved in some organizing to support what they were doing. And there was a new film that had just come out, a documentary about the GI movement during the Vietnam War, which I had never heard anything about. But so there was like a fundraiser for IVAW, where they were screening David Zeiger's film, "Sir! No Sir!" which is this documentary about that movement. And in that film, there are clips from the FTA film that show that show. And so this was the first time I knew anything about this anti war variety show that played to active duty soldiers. And from there, it became a sort of a research project, a paper I wanted to write. And then eventually, it became clear that there was a whole set of questions that I could explore through this one pretty short lived theater event from 1971.

Kelly 12:07

And so what are the kinds of sources then that you're able to use? I understand you interviewed some of the participants were, you know, what all are you able to pull together for this?

Dr. Lindsay Goss 12:18

Well, the first thing that happened was that another grad student at Brown, who had been working on the GI movement, writing about it, sort of handed me this sheaf of photocopied articles that he had looked at when he was researching at, in Wisconsin at the University of Wisconsin Madison, I believe, from their archives on the GI movement. And he sort of gave me all of the ones that pertain to the FTA show. So that was sort of a starting point of really starting to piece together just how there had been this entire history of the show before the tour that there are clips of Zeiger's documentary. And I started just piecing together actually, actually, this had a huge audience, actually, it was wildly, you know, it was really positively received by by its audience. And I just wanted to sort of piece together that narrative, and that at a certain point, yeah, I started reaching out to people who had been involved. And it was one of these things where I got a hold of one person, and they sort of directed me to another person, and another person and another person. So it did sort of transform from this kind of archival material basis into this more oral history kind of basis. And then alongside that, a lot of what was informing the book, sort of methodologically it was my own experiences as an activist and trying to sort of think those through what I was learning about this particular project from from '71.

Kelly 13:45

So I was looking at a New York Times review of the film when it came out in '72, and it said something like by now everyone's heard of this Free Theater Associates. I was like, "Okay. But nowadays, nobody's heard of it." So what what happened? Why did this become something that is really not very well known today?

Dr. Lindsay Goss 14:06

Yeah, I think there's basically, I mean, there's probably more than two answers to that question, but there's two that I think are helpful to understand. So one thing that happened is right after the film comes out in '72, it's pulled from theaters. And the director Francine Parker, told David Zeiger that she believed that was because there was a call from the White House to Sam Arkoff, who was the head of AIP, the production company. So that's one thing, right? Like the film just sort of disappeared. Apparently most copies were destroyed, and it really wasn't until David Zeiger remastered it and re released it in in the 2000s that it became available again. And I like the reason why he did that is because he wanted to include footage from FTA to film in his documentary, "Sir! No Sir!" And Francine Parker said yes, you may so long as you also remaster and rerelease FTA itself, so they sort of came out around the same time as a result. So that's one piece of it. Tthe film disappeared, and then that was the primary way in which people moving forward would access information about this show. And so that was not available, but I think the for me, the more important answer to that question is that the GI movement was basically erased from our history and picture of resistance and protest in the 1970s. And I think that was quite intentional and deliberate, even as it was happening, there were just continual efforts to say that it wasn't happening, that, you know, there wasn't sort of hundreds of underground newspapers circulating, that there weren't soldiers participating in protests. And a big part of that is that, you know, as, as soldiers were coming back, you know, as veterans were sort of entering college or participating in protests, sometimes they stopped looking like veterans, right, they sort of could, you know, merge with the kind of picture of the 1960s and 70s radical, especially like young, radical students. And if you think about it, I mean, the idea that there were 1000s of soldiers, more than that, probably in the military, expressing resistance to it and organizing against the war. You know, that's not necessarily something you want people broadly to be familiar with, if you're invested in the military as an institution, and in its projects. So I think the the sort of the, the erasure of the GI movement, is why the FTA also would not be something that registers and it's also why Fonda's legacy could turn into a very anti soldier, one, because people are familiar with her anti war activism that looks like her going to North Vietnam. But they're not familiar with what came before that, which was her extremely committed activism in support of the GI movement of soldiers who were saying they were against the war.

Kelly 16:53

It wasn't just soldiers who had been drafted, right? Like this is a more widespread movement than that.

Dr. Lindsay Goss 16:59

Yeah, and that's a really important point. There's an excellent book by David Cortright, called, "Soldiers in Revolt," which was actually I think, his dissertation about the GI movement. I mean, this is from I think it's published in the 70s. And then it was rereleased later by Haymarket Books. But he is pointing out and showing statistically that in terms of the GI movement, it would be absolutely not the case that it was exclusively draftees. In fact, there was a real sense of betrayal on the part, especially of young people who had signed up to serve, and then found that what they were being asked to do, you know, on a pretty basic level didn't make any sense. Yeah, that there was a sense of betrayal there. And I remember that from that was a really important theme in the context of Iraq Veterans Against the War as well, that a lot of the folks I mean, there's no draft, right? So they weren't drafted. But a lot of the conversation I remember was around this sense of betrayal, of finding out what exactly it is that you're being asked to do, and in whose interests, and they're not yours, and they're not really the interests of anyone, you know.

Kelly 18:02

So what is the goal then, of FTA? They want to support the GI movement, support the troops, you know, what, what's their vision of how they're going to do that?

Dr. Lindsay Goss 18:13

Yeah, so I think the vision transforms over the course of the life of the show, although I mean, it retains sort of its starting vision, which initially, they're sort of framing it as it's just entertainment, you know, we want to show soldiers we're there for them. But that we're anti war. It was in many ways conceived as a counter to the Bob Hope Show, which was, you know, a sort of patriotic, pretty much pro war, even if most of the humor wasn't really about being pro war, more about military life enlisted life, right. So it's initially conceived as kind of entertainment, anti war entertainment, for soldiers who are really only getting pro war entertainment. And it's also I think, a way for these celebrities, and Fonda in particular, to sort of use what they do to support this movement that they're aware of, of soldiers against the war. And one thing they emphasized really clearly early on, that I think is, is related to the question you're asking is that they emphasize that they can't tell the soldiers anything they don't know. So their vision isn't that they're going and preaching to the soldiers about why they should be anti war. Anything they're communicating to the soldiers is sort of a reflection back of what is already part of the sort of GI movement conversation. This took some really explicit forms like taking material out of GI newspapers, right. So at a certain point as they're touring in the US, there's a writer, Robin Menken, who really starts to make a point of asking for copies of newspapers at a particular base to be sent to her so that she can write material based on what the soldiers actually are doing, and thinking about and trying to protest or resist or whatever that may be. So there was this real sense that they are, they are amplifying what the soldiers are already saying. And that that amplification is both in service of growing the GI movement, right. So you probably have some audience members who are attending because Jane Fonda is going to be there and not because they're already particularly invested in the GI movement, but then who are hearing sort of through these celebrities, the voices of their fellow soldiers, about what's going on. So it's really interesting kind of, I don't know, circle or something of how this content is moving through the performers and through the audience. And then the other piece of it, I think, is that because you had celebrities involved, it was a way of then communicating to the civilian population, that there were soldiers who were opposed to the war, right. So when there's coverage in newspapers of the FTA show, and especially the first show, so much of the coverage is about the audience and about how they're responding. And often, there's a really great Village Voice article where there's interviews with soldiers afterwards about the show, and about how they're opposed to the war. The film does that as well. So much of what we see is the soldiers. So I think, fundamentally, the show was about showing soldiers to themselves, and about showing those soldiers to a civilian population.

Kelly 18:53

So logistically, unlike the Bob Hope Show, they get no support from the military itself, never gets to go on to a military base to do any of this. So how are they able to then put together the tour first within the US, and then they do this Pacific tour and get to soldiers without getting on bases?

Dr. Lindsay Goss 21:45

Yeah, it was a big project. So there was already at this point, the coffeehouse movement in the US and also abroad, where there were sort of radical or even just sort of hip, off base coffeehouses, often run by civilian organizers, or a combination of like veteran and civilian organizers that were meant to be spaces where soldiers could go away from kind of the scrutiny of the military, and be around other soldiers who maybe were opposed to the war, or maybe had, you know, radical politics. And so that became the primary way they were able to access space. So sometimes it would be about performing at a coffeehouse, which is what happened with their first performance. Outside of Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina, they performed at the Haymarket Coffee House. And these are not big spaces. So often, there are multiple shows people are packed in. But then there were shows in larger spaces or outdoor spaces. But generally, regardless of the specific space, whether it's a you know, an auditorium that they rent from the city, or whether it's a coffeehouse, or you know, a park, the local coffeehouses and the organizers involved in those, both civilians and soldiers and veterans, were basically the way they were able to organize these tours. So that's, that's that mechanism there. It was way more complicated with the overseas tour. And I was so fortunate to get just this stack of correspondence from Elaine Elinson, who was the advance person, so she went to all the places they were going to perform, reported back on the venues, reported back on local issues, and even just political context. So you know, they were going to the Philippines in a really tense moment politically. So there's all this correspondence about how to talk to the press, what sorts of events they're going to have to do so that they don't raise any concerns, like they're going to have to give medals at a at a swimming competition. So overseas, it was it was really logistically complicated. But it was all through these networks of civilian and veteran and soldier organizers, sort of figuring out the the landscape in each given place, and what was going to be possible in terms of a show, a space, the content that should be included.

Kelly 24:11

Could you talk a little bit about as a theater historian, the difference between the US shows and how you're able to access those. So that's through, you know, people's memories, or from things that are written about it. And then the Pacific shows which we actually have film of like, how, how you think about those differences, because it must be a much different experience.

Dr. Lindsay Goss 24:36

Yeah, that is such a good I hadn't quite thought about it that way. That's a great question. But it's totally true. I mean, the trying to reconstruct, the tour as a whole relied heavily on newspaper coverage and then the correspondence from the later tour. But right in terms of actually accessing what the performances were like, yeah. I don't have that for those earlier ones. What you're making me think about is the fact that I had this other really weird experience of talking to people, because the show changed really significantly over the course of its domestic tour. And it was pretty fixed when it went on its tour overseas. It was all the same people the whole time. They had the same crew the whole time. You know, that was, that was pretty set. And there was all that work to sort of lay it all out in advance. Obviously, there were things that came up, you know, I have a footnote in the book where I say, you know, I might be wrong. Sometimes, in correspondence, I can't be sure if what is proposed in correspondence ever actually came to pass. But even still, I feel like, it's useful information to understand what the project was, even if I can't say with certainty that like X, Y, or Z happened, because it's not in, you know, a newspaper article. But domestically there, people had really different understandings of what had happened before they joined. So a lot of people I talked, I mostly didn't talk to people who were involved in the first show, I mostly talked to people who were involved starting later in the spring, or who got involved, really just for the tour overseas. So that too, was this, I mean, I was constantly sort of navigating these different inputs and trying to figure out how they related to each other. And I also had to figure out when the people I were talking to people I was talking to were wrong, which is weird to say, but you know, when, when actually somebody must be misremembering when or where something happened, because all of the other evidence points in that direction.

Kelly 26:43

This is a time period, of course, when the military is facing a lot of racial unrest. There's just a lot at the country as a whole, but also the military is facing racial unrest. It's a time when Jane Fonda is starting to think a lot more about women's issues and gender. So can you talk about how all of that informs how the show changes over time, especially before it goes overseas?

Dr. Lindsay Goss 27:10

Yeah, it really changes so much. And I think it's a couple of different sort of primary influences. So the first show is an all white cast, except for the comedian and activist Dick Gregory, who performs alongside the group. And it's also an exclusively male cast, except for Fonda and Barbara Dane, who's a folk singer, and it's really pretty, the content is quite contained to the issue of the war, to military life, and sort of presumes, I think, like a white male audience. Now, predominantly, their audience is white and male, but not exclusively, certainly. And, obviously, well, at least I am interested in how questions of class and militarism and all of that intersect with race and gender and all of that, but, but that happens sort of later for the for the show. But initially, it's, yeah, it's really kind of targeting, it's, it's politically narrow. And it's intentionally politically narrow, because they are trying to make this argument that, you know, we're not any crazy radical show. We're just entertainment. We're just an anti war entertainment program. And I think for some people involved, that was a tactic that was like a way of kind of pursuing publicity, that wouldn't just write them off, as you know, a radical project. I think for other folks, it was that is what the politics of this should be. We shouldn't be trying to talk about women, we shouldn't be trying to talk about race, we need to just focus on this one issue and not address this other stuff. And there's a back and forth around the first performance, that for me, is sort of the foreshadowing of how these issues are going to get raised later. When there's a chorus of there's correspondence between one of the writers, Jules Feiffer, and a couple of women organized civilian organizers. And apparently, they are writing to him because they heard that he wanted to include a sketch in the show that would involve Jane Fonda coming out dressed as one of those girls, I'm quoting, that Bob Hope always brings with him on tour, which means like, a bikini, Jane Fonda in a bikini. And this is not long after Barbarella. So like, yeah, that probably would have been super appealing to their audience. And the women organizers are like, "This is not okay, we're gonna like cut the lights on you." And he writes back and he's like, "Look, I think it's parody. I don't know what you're so worked up about." And for me, like this is such a key question like, can that be parody? What is what is that at the expense of and is is it legitimate to sort of pursue this anti war politics through a kind of reliance on pre existing ideas about the role of women in military entertainment. So that's that's the beginning, right that that question could even sort of or that that premise could even be proposed. And then I think at a certain point, Francine Parker gets involved. And this precipitates in many direct ways, as do some other interactions Fanta has with some women organizers during the domestic tour, sort of precipitates this, this kind of militant feminism in the group, which Fonda adopts and is certainly part of the politics of some of the new people they bring on board, including Robin Menken, who I mentioned earlier. And so they start trying to figure out how to write material that absolutely retains its focus on the US service member, or service man, but also starts to think through the relationships between militarism, between imperialism, between the sort of class dynamics of the draft and enlistment and think, think that in relation to the experience of women, both in the military and not. So they end up with this central character in a new set of sketches called Kitty Mitty, who, who's sort of we see things through her eyes, which is a totally new thing in the show, sort of by the end of the summer. So it retains an emphasis in a way on, you know, what is going to be the more common set of experiences among their sort of audience's demographic, but while trying to make those links. In terms of race, there is not quite the same, really sharp turn. But there is a deliberate effort to diversify the cast. And that results in a lot of material that more directly more explicitly reflects elements of the experience of a Black service member. So there's two new performers, Pamela Donegan and Rita Martinson, who, you know, are introducing music and spoken word that really feels like it connects more directly with Black audience members. And then and the other really critical thing about this is that when they go overseas, because of the militancy of Black servicemembers, there's a number of contexts in which sort of access to Black soldiers to talk to them about their politics and their perspectives on the war relies on those Black cast members because of a sort of a Black militancy and nationalism. They want to talk to those Black cast members, and not to the white cast members. There's also some, I found some sketches, some written sketches, that, to me feel like they relate to another movement of that period, called Black Revolutionary Theater, are these really sort of often very short, powerful performances that are addressing you know, issues of racial violence, racial oppression, and white supremacy. And I found some written sketches, I have no idea if they were ever included in the show. There's no representation of them in the film. No one, I asked people about them and no one knew or remembered. So there seems to have maybe been a way the content was reflecting that. But I cannot say for sure if they were actually performed.

Kelly 33:10

We've been mentioning Fonda. Another important person in the book, the show in the film is Donald Sutherland, who just passed away recently. Could you talk a little bit about him in his role, you know, he is the the white guy, but he he's able to play these really, he sometimes plays like the straight man in the skits. So could you talk a little bit about that?

Dr. Lindsay Goss 33:31

So Don Sutherland is there in the beginning, he's there through to the end, he seems to have gotten involved in supporting the GI movement a little bit before the FTA. And, and differing accounts will place him at the meeting of Fonda and Howard Levy, when the idea was discussed. There's also plenty of times I've seen that meeting, referred to without any reference to Donald Sutherland. But I feel like that kind of makes sense. Like that kind of seems to be his relationship to this project. And I don't mean that in a bad way. Like, I think he actually, if you look at descriptions of him as an actor, which I was doing recently, after he passed, there's a real correspondence between the description of his acting and the way I think he related to the project of the FTA, which is this kind of there's a term in theater called "throwing focus," where you might be in the scene, but you're meant to be helping the audience pay attention to someone else, or to something else that's happening. And that's a useful way of thinking about the FTA show, generally, right? Like it was a performance but it was also meant to sort of throw focus onto the GI movement for a civilian audience and even for the soldiers themselves. So I think in some ways, Sutherlands Sutherland's relationship to the show that that he, you know, he doesn't talk a lot in the film. He hasn't ever really talked about being in the FTA. Apparently, there's an unfinished autobiography. So I don't know if that will address that part of his life. But what is I mean, as I said he was there in the beginning, he was there till the end, I mean alone among the men who were there on that stage on the, you know, at the opening performance, he sort of weathered that feminist reckoning. And I think that that's a really powerful testament to his investment in and support for the GI movement. He also had this one thing that he would always do at every performance, I think it literally happened at every performance that the FTA did, which I'm not sure there's anything else, you can say that about maybe, maybe this sketch called Red and Red. And he did this, he had done this before starting the before his involvement in FTA, when he had started participating in some civilian support actions for the GI movement, which is that he reads this passage from Dalton Trumbo's book, "Johnny Got His Gun," and it's the final passage from the book. So just a very brief summary of that book is that there's a soldier in World War I who is in a bomb blast, and he loses all of his limbs, he loses basically all of his face, his eyes, his ears, his tongue. And so he's lying in a hospital bed, and he figures out, he can communicate by tapping his head in Morse code. And what he wants to do and what he communicates to these military officials is that he wants his body to be put on display and toured around the world, so people can see what war does, and, and he believes that that will mean the end of all war. And he realizes that will never happen, that they won't I mean, they say no, basically, right. And so in this final passage of the book in first person, he basically says that, if if men in the future try to make us fight a war, we will turn the guns on them. I mean, it's this really beautiful moving speech. And it's actually at the end of the FTA film, we see Sutherland perform some of it. And he had been performing this, or performing reading this at a Operation Rapid American Withdrawal, which was a VVAW action. And then he did it for every show. And it's often described in coverage of the show, as this totally implausible, but deeply successful moment of sincerity and quiet in this in the midst of what is otherwise, you know, sometimes a kind of like, not hokey, but comedic, like sketches, you know, a little bit of slapstick, right. But somehow, Sutherland could create this, just this, like, incredible weight in the middle of the performance. And I only just recently realized, which was a little embarrassing as a researcher, that Sutherland was in the film adaptation of that book, in '68, or something, and plays Christ in in the movie. And it's an amazing performance. I mean, it's, it's totally devastating. But I just became really interested in the idea that, like, Donald Sutherland encountered this book and encountered this speech, and he was like, "You know what, I'm just gonna keep doing this, like, I can do this. I'm gonna keep doing it." And it's really effective. So yeah, I've been thinking a lot about Donald Sutherland, and really appreciating him and his role in FTA.

Kelly 38:17

At the end of the book, you start reflecting a little bit on what we can learn from the FTA and perhaps apply to today. Not that there's any political protest that needs to happen today. If you could just reflect on that a little bit now.

Dr. Lindsay Goss 38:33

Yeah, it's a big question. Yeah, I mean, I think where I arrive at the end of the book, and I have to say the conclusion of the book is, I really like it. It really led me it's sort of it was where I figured out the thinking that the FTA had let me do. And a big part of the takeaway for me, and this is after spending a lot of time thinking about the discourse of acting as it sort of was attached to 1960s protest. And that's true of the GI activists who are sort of written off as not real soldiers. It's true of Fonda, who, really from both the left and the right, got a lot of grief for being an actor who was involved in political activism. Yes, the book let me think a lot about acting in relation to political protest. And I think the takeaway for me is that it can be really awkward and embarrassing to be an activist. It can feel like you are pretending that things are possible that aren't possible. A lot of times it can feel like and I'm speaking from personal experience, it can feel like or you can be afraid of being accused that you are just sort of pretending you are in the past. Right like you see it right now. You see it a lot right now. The Bill Maher comment about cosplay among students protesting and having the encampments about what Israel is doing in Gaza, saying it's cosplay that the students are wearing kofias. That's exactly the rhetoric I'm talking about, like, there is no way engaging with the substance of what the students are saying, or what they're doing, or what is happening right now. It's saying, "You're faking it, right? Like you're pretending." And that's so much of the discourse during the 60s in the efforts to downplay the existence of the GI movement, and to say that veterans who were taking a principled position against the war, were pretending right, like, it's not even saying they're wrong. It's not even saying what they're saying isn't true. It's like,"Oh, they're not really entitled to take a position or to say anything, because being an anti war veteran means you're not really a real veteran." I mean, it's crazy, like it can make you feel crazy. And we see the same thing in the sort of aftermath of aftermath of the 60s like following the 60s, you get all this sort of discourse that wants to rewrite the 60s as just a bunch of people pretending or playing around. And we see that now too, especially from the right, I mean, this next project, I'm working on, really trying to think through the idea of the crisis actor, right, which is, you know, a term people might have heard used about student survivors of school shootings. Either they're totally just actors who are pretending they were there to pursue gun control, or they were really there, but there's something disingenuous about their activism, right, like they're being opportunistic or something. So it's totally we see it transparently on the right, right, this rhetoric of discrediting people by saying, they're not the people who, like they're not the people, they say they are, basically and we can also stretch it way back, right, like, you know, discourse around school integration. Right. And, and these theories that the Black students tried to integrate a school were like bussed in from outside of town. It's like, even if they were right, does that actually fundamentally discredit the project of integration? So there's, there's just such a long history of this, and I see it so potently right now. And I think it's really insidious. And I'm also, you know, I also feel like activists and sort of people, kind of towards the left, I see sometimes a tendency to want to adopt some of that premise and like, protect against it by by appealing to ideas of authenticity. I think we see some of that in, right, like their book is sort of sometimes this kind of self policing of movements that I think isn't quite the answer, right? I think that, that if you are proposing the world can look different than it does, then you're undertaking like a super precarious project, that is not totally unlike what actors do. And I think if we maybe can understand a little more clearly, that dynamic, we might be less inclined to, I don't know, make ourselves smaller in response to like accusations that we're just pretending or it's not real, and instead be like, well, we're gonna make it that way like this, you know, this is the project. And so yeah, I just, I think I'm really in that final passage, trying to say, "Yes, this can be weird and embarrassing, and we can feel like we're pretending," but maybe that's what it is to try and argue that things should be different than they are.

Kelly 43:51

This is a terrific book. We haven't even talked about any of the Hanoi Jane stuff. So please tell listeners how they can get a copy.

Dr. Lindsay Goss 43:58

Yeah, great. Oh, and thank you so much. You can I think it's generally, if you Google it, you will find it. I know it's on bookshop.org, which is cool. You can also get it straight from NYU Press. And if you do that, and you use the code NYUP30, you will get 30% off. It's also available as an ebook, which I think is great. So it may be that if you tell your library to get it, they might. I just told my university library to get it. And they did. Yeah, I think generally generally accessible. You can read an excerpt on History News Network, and you can read a piece I wrote about Donald Sutherland's involvement on of all places, foreignpolicy.com, Foreign Policy Magazine Online. So yeah, I think relatively accessible.

Kelly 44:48

Lindsay, thank you so much. I loved learning about the FTA and I'm so glad you spoke with me today.

Dr. Lindsay Goss 44:55

I'm so glad too. Thank you so much, Kelly

Teddy 45:23

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Lindsay Goss

Lindsay Goss is a theater historian, performance theorist, and theater artist. Her work explores how popular discourses of authenticity and identity rely upon historical anxieties about the actor in proximity to politics, and how these anxieties shape the fields of theater history, activism, and contemporary performance. Her current manuscript focuses on the theatrical tactics civilians and soldiers deployed in building a GI movement against the Vietnam War (including the FTA, an anti-war variety show led by Jane Fonda) and argues for a reassessment of the role of performance and spectatorship in theorizing contemporary activist movements. Her scholarly work has appeared in TDR, Contemporary Theatre Review, Performance Research and Afterimage. As a director, actor and teaching artist, she has worked with companies in Minneapolis and St. Paul; New York; and Providence, Rhode Island. More recently, her devised work has appeared in Abu Dhabi and London. She directed the world premiere of Marisela Treviño Orta’s play Somewhere at Temple in the spring of 2020.

Lindsay earned her PhD in Theater and Performance Studies from Brown University and her BA in English Literature from Macalester College. lindsaygoss.com